It is not an easy time for those working on climate accountability across the English-speaking world. The Trump administration has launched a blitzkrieg on environmental and climate regulations in his first 100 days in office. Over in the U.K., former Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair, who today works as a paid consultant for the governments of Saudi Arabia, UAE, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, published a report suggesting a phase out of fossil fuels is not possible. In Australia, the conservative opposition party took a platform to the recent 2025 federal election with a pledge to strip away environmental and climate policies like copper wire from an abandoned building. They ultimately failed, but not without forcing a year-long debate about the merits of creating a nuclear power industry from scratch in a country with some of the highest renewables penetration in the world.

Buried within this flurry of headlines was a story that suggests accountability for the historical actions of fossil fuel producers on climate change may not be as impossible as it seems in this political environment. A pair of climate researchers say they have come up with a method to link individual fossil fuel producers with specific climate harms in a way that would allow courts to quantify the economic loss. More than that, the researchers say that when they ran simulations using emissions data from the five biggest fossil fuel companies in the world – Saudi Aramco, Gazprom, BP, ExxonMobil and Chevron – they found the price tag for one kind of climate harm alone ran into the trillions.

Right now there are several major climate lawsuits within the U.S. against major U.S. oil companies, including Municipalities of Puerto Rico v Exxon Mobil Corp et al—a racketeering case against multiple oil companies, trade groups, think tanks and operatives for conspiring to mislead the public and obstruct climate policy, which cleared motions to dismiss earlier this year and is proceeding towards trial—and other cases brought by individual U.S. state and local governments, seeking to hold fossil fuel producers to account for their role in driving climate change. Dozens of those states are still active, despite the Trump administration's move to sue some of the states bringing these suits in an effort to stop the cases from moving forward. At the end of April, Hawaii became the latest U.S. state to take action against fossil fuel producers, which the Trump administration immediately moved to block with a countersuit. The U.S. is not the only jurisdiction to experience a wave of litigation; there are more than 1800 cases active worldwide, and Australia alone has recorded 627 cases according to Melbourne Law School’s Climate Change litigation database, making it the second most active jurisdiction for climate litigation.

Holding individual oil and gas companies to account for specific climate harms, however, is not easy given the scientific and legal questions involved. With tobacco and asbestos litigation, individual companies could readily be linked to specific harms, but with climate change the problem is more complex. It is one thing to show that climate change causes extreme heat, but it is another to then show that the emissions created when a particular company’s oil, gas and coal is burned increased the intensity of a particular heat wave by some amount – and then to put a dollar figure to it. To date, risk-averse courts have been hesitant to address these questions with courts in jurisdictions like Australia appearing to be waiting for a precedent to be set in other jurisdictions, like the U.S. or the Netherlands.

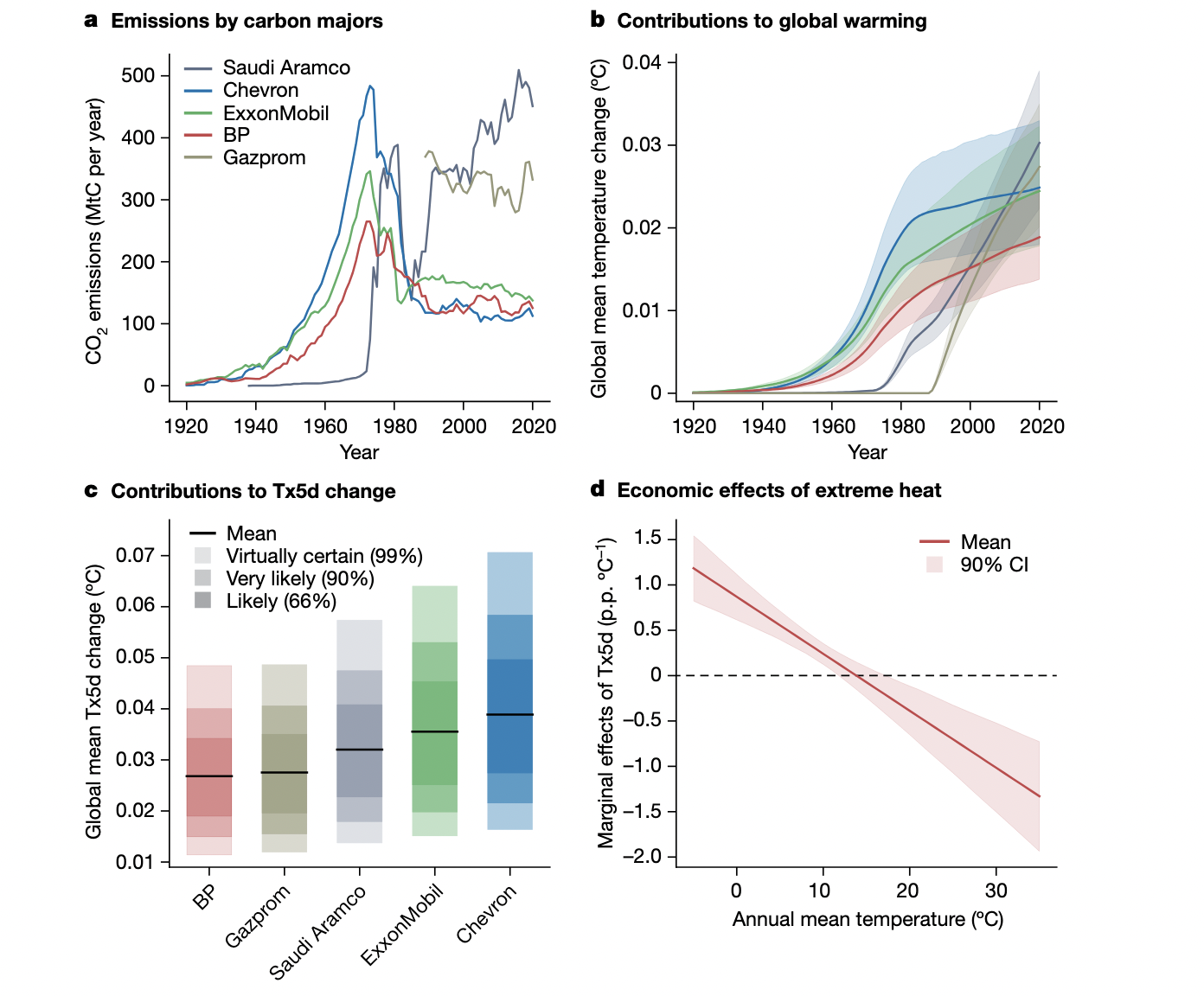

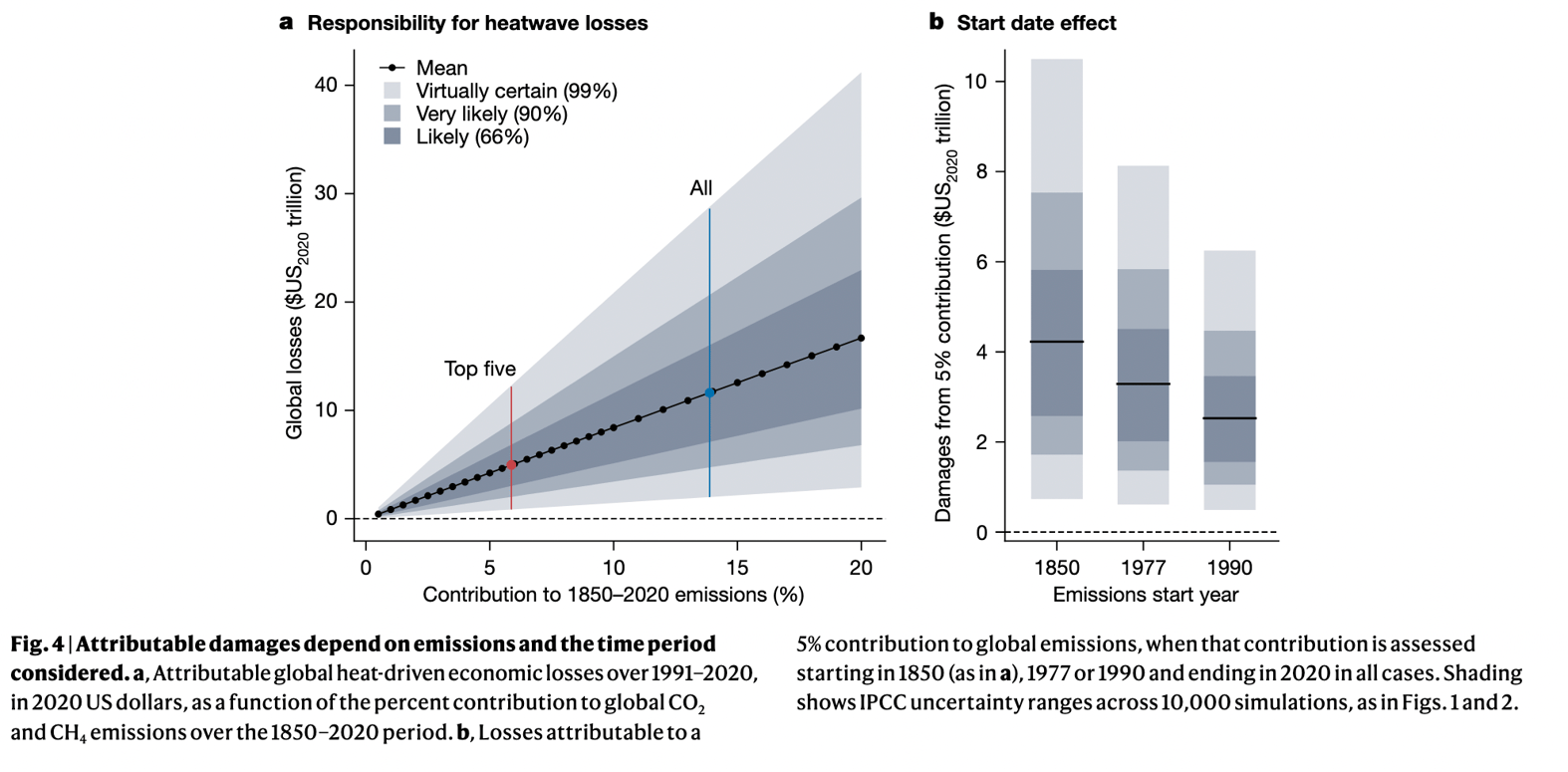

The peer review paper published in the journal Nature in April by Christopher Callahan from Standard University in California and Justin Mankin at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire seeks to answer the scientific issues associated with these questions. Looking at the period 1991 to 2020, the researchers drew upon historical emissions data for the five biggest fossil fuel producers and then sought to understand how the emissions from these companies contributed to one kind of climate harm: extreme heat. This was defined as the temperature of the hottest five days in a year and chosen because the available scientific research linking extreme heat to climate change processes is well established. Drawing on work by several other teams, the researchers sought to develop a replicable method that could apportion responsibility to one company, and then quantify it in dollar terms.

“Even just from that, we get numbers in the trillions,” Callahan says.

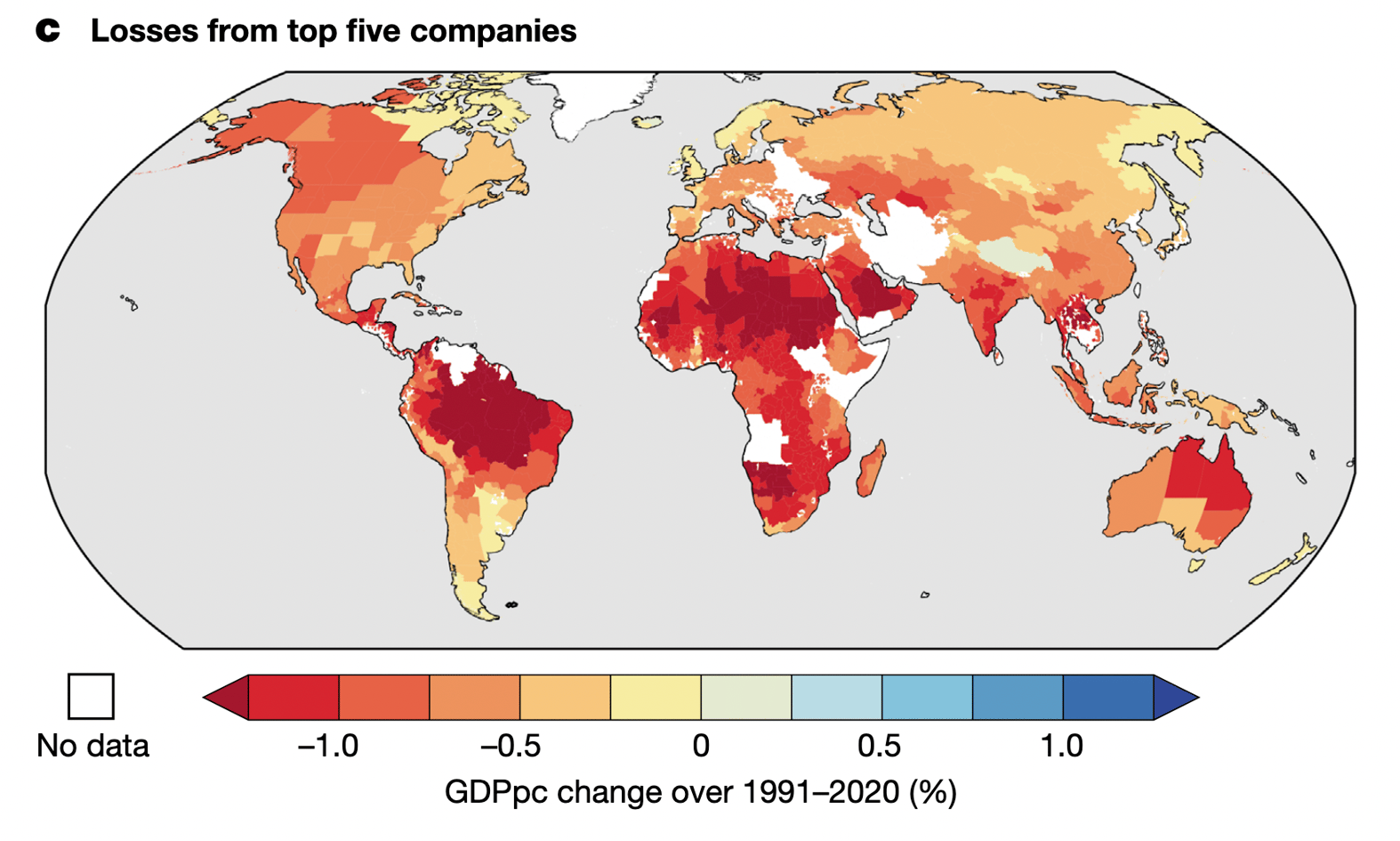

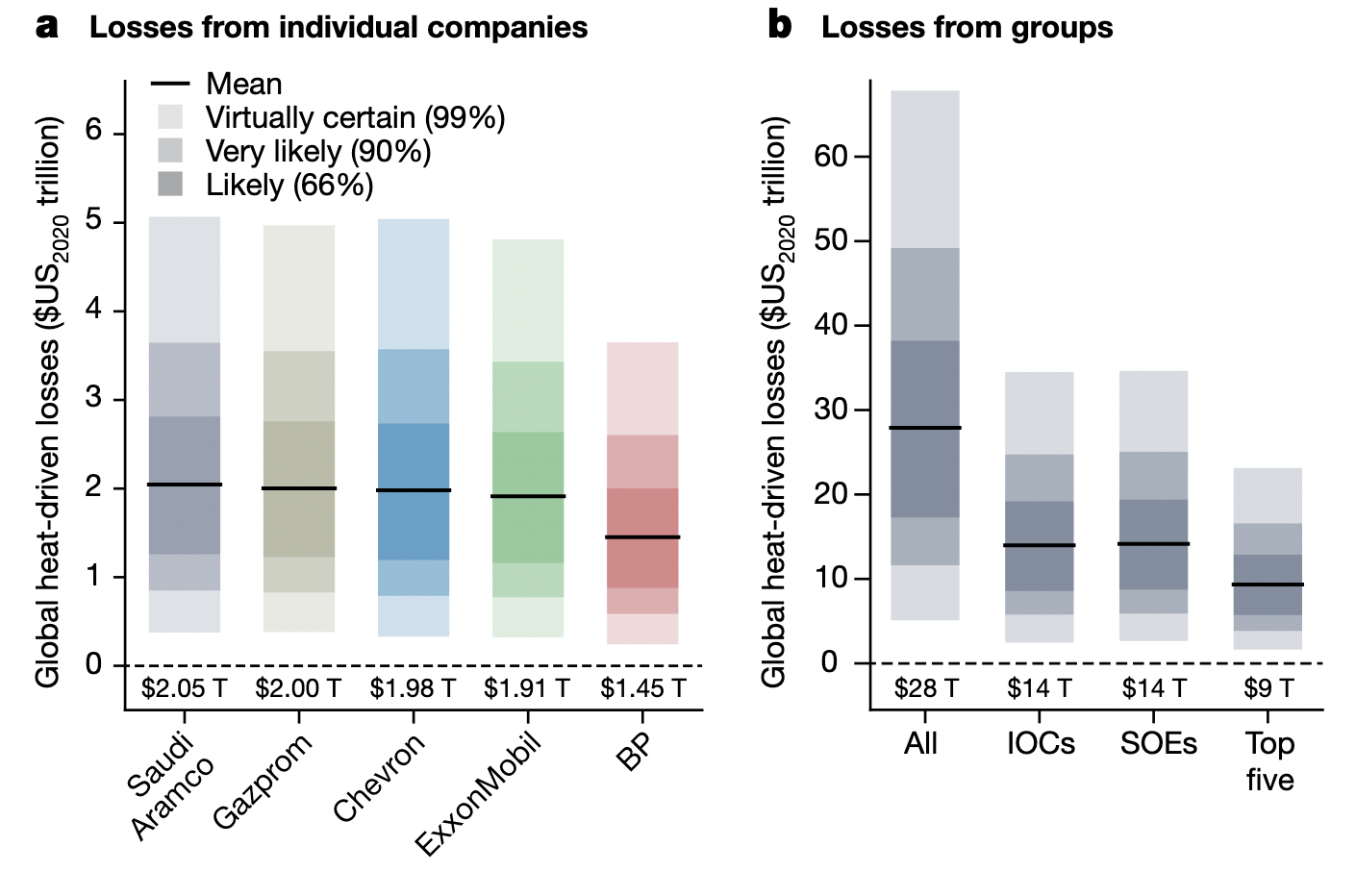

Calculating that cost involved drawing on the best available research to assign a monetary value to every unit of greenhouse gas emissions produced when oil, gas or coal is burned. Their work suggests that state-owned oil companies Saudi Aramco and Gazprom were responsible for U.S.$2.05tr and $2tr in damages respectively. Chevron, ExxonMobil and BP were each found to be responsible for $1.98tr, $1.91tr and $1.45tr in losses respectively. In a separate analysis of emissions data not included in the study, performed at the request of Ketan Joshi, Callahan also looked at five major Australian resource companies – BHP, Rio Tinto, Santos, Whitehaven Coal and Woodside Energy – and assessed the total damages from their collective emissions at more than U.S.$600bn, or A$929.47bn.

“It's not like trillions of dollars being lost in any individual heat wave –it’s all the heat waves around the world for the last 30 years,” Callahan says. “And when you add up, you know, global GDP over that period, it’s in the quadrillion and so, ultimately, as a percent of the global economy, it's not actually that large, but it is still trillions, and that's a significant number.”

The analysis, however, looked at just one climate harm. Callahan says that when the full range of other harms are factored in – such as drought, flood, fire, smoke and sea level rise – the total liability presents a nightmare for fossil fuel producers that have long-feared tobacco-style lawsuits. Among coal, gas and oil producers, awareness of the risks posed by climate change evolved out of concerns about smog above Los Angeles in the 1940s with alarm growing in the 1990s in response to lawsuits filed against tobacco companies over their role in causing cancer. To get ahead of the problem, industry asked its researchers to investigate the greenhouse effect throughout the 1960s, 70s and 80s, but kept its conclusions quiet. As it sought to better understand the problem, the industry simultaneously embarked on a multi-decade campaign – coordinated in part through an appendage of the United Nations today known as IPIECA – to stay ahead of attempts of governments on the issue and ensure they did not act quickly to address it.

Though there is still “a long way to go” before a tobacco or asbestos-style lawsuit succeeds, Callahan says the paper is significant for showing that accountability is possible.

“It is no longer scientifically supported for actors to argue that there is plausible deniability, that it is impossible to link any activities of an individual actor to any impact of climate change,” Callahan said. “That statement, that there is a sort of uncrossable gap between where you emit and some other impact down the road, we’ve shown that to be fallacious.”

“Until two weeks ago, it was unclear whether it was scientifically supported to say an individual emitter can be linked to the impact that you’re suing over or that you are trying to recoup costs for," he added. "That scientific connection can absolutely be made.”

In a real-world illustration, Australian oil company Santos was asked by the Australian Conservation Foundation, during consultation for its environmental approval, about whether it had properly considered the potential climate harms from its plan to build and operate the USD $3.62 billion (AUD $5.6bn) Barossa gas field. The controversial project has variously been called a “climate bomb” and a “carbon factory” owing to the relatively high level of carbon dioxide present across the field. Santos responded by arguing “there are limitations to linking emissions from the activity to any specific climate change impacts”.

“Santos invited ACF to provide further information regarding how it is able to undertake an analysis that links climate change impacts from the activity to specific environments or ecosystems,” the company said.

With the science now sufficiently advanced, Callahan says industry can no longer wave off these sorts of objections. Legal objections, of course, are a different story. How courts or regulators will answer these questions going forward remains to be seen, as the same set of facts may be handled differently in the U.S., the Netherlands or Australia.

“The importance of this work, in my opinion, is less in the precise numbers we provide, and more in the demonstration that this kind of attribution is scientifically supported or scientifically feasible,” Callahan says.

“Our work is looking at linking emissions to impacts, that doesn't say anything about the fact that the fossil fuel industry knew about the dangers of their product and attempted to hide it from the public, and attempted to promote campaigns of disinformation and delay with respect to mainstream climate science.”