This article was co-published with Rolling Stone and supported by the Pulitzer Center.

In the leadup to the annual United Nations climate negotiations—known as the Conference of the Parties, or COP—it’s become increasingly common to see dismayed headlines about the number of fossil fuel lobbyists attending, the oil deals expected to be done on the sidelines of the conference, and the placement of oil executives in leadership positions.

As former UN leaders Ban Ki-moon and Christiana Figueres join global climate leaders in calling for an overhaul of the system, documents newly uncovered by Drilled reveal that the fossil fuel industry’s influence over the COP process was a foregone conclusion, embedded into its design from the very beginning.

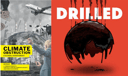

The first UN meeting on global environmental issues—including climate change—was held in Stockholm in 1972. It was a new idea at the time to approach environmental issues from a global perspective, and one that many industries perceived as a threat. While the organizers of that Stockholm meeting did their best to keep polluting companies at arm’s length, documents released by the Climate Investigations Center in 2022 revealed that the U.S. government came to polluters’ rescue. In 1970, President Nixon created an industry-staffed advisory panel within the Department of Commerce that gave CEOs from companies including Exxon, Mobil, Dow Chemical, Pepsi and more direct access to the senior State Department official Nixon had tapped to lead US preparations for the Stockholm conference: a former Mobil public affairs executive named Christian Herter.

As the conference was underway in Stockholm, The New York Times reported that although industry heads were complaining about not having been given an official seat at the table, the U.S. government had made up for it by giving industry representatives “several seats on the 35-member U.S. delegation.” The Times went on to note that “the representatives included Frank Ikard, president of the American Petroleum Institute.”

New internal documents uncovered by Drilled from ExxonMobil, Eni and Total Energies reveal that the fossil fuel industry moved quickly to decisively counter any progress made at Stockholm, and to successfully gain permanent seats at the table during international environmental negotiations. Far from seeing the United Nations Environment Programme, or UNEP, as an obstacle to business as usual, polluters used it to coordinate the industry-preferred response to climate change and to embed that response amongst various heads of state and negotiators, influencing not just the eventual drafting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992, but also every Conference of the Parties (COP) to that convention since.

In the lead-up to Stockholm, looming global environmental challenges centered the fossil fuel industry in particular. In 1967, the British air force bombed the SS Torrey Canyon with napalm in a doomed effort to contain a disastrous oil slick. Two years later, the U.S. experienced its largest oil spill at the time, an event that turned the beaches of Santa Barbara, California black and sparked the creation of Earth Day. Public awareness about the risk posed by the greenhouse effect was beginning to spread as well.

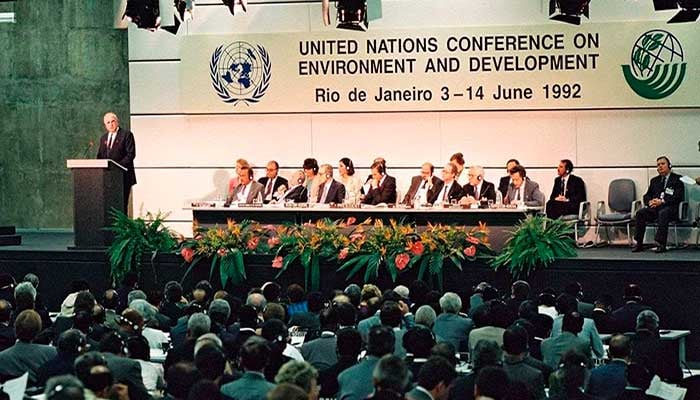

Against this backdrop, there was a growing feeling within the international community that given the global nature of various polluting industries, it would be helpful to have a point of contact on issues that concerned each industry. Documents show that one of the early agenda items for UNEP was the creation of an Industry Program that could enable UNEP to work directly with various polluting industries. By 1973, the petroleum-focused group already had a name—the International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association, or IPIECA. Even before the UN announced the official launch of IPIECA, Exxon had taken a leadership role in it, hosting one of the first meetings to discuss the group at its headquarters in New York. Herter got involved here too, coordinating a UNEP trip to Houston to “lay the groundwork for a potential initiative.”

Memo on left from the ENI archive, retrieved by Greenpeace Italy; memo on right from the Maurice Strong Papers at the Harvard Environmental Sciences Library, retrieved by Drilled.

It helped that the global oil industry had a friend in the founding director of UNEP, a Canadian oil man named Maurice Strong. Although letters between Strong and various advisors show his concern over allowing polluting industries too much influence, and the need for guardrails, he also spoke throughout his life about industry as a force for change. His letters reveal an unshakeable conviction that companies would ultimately do the right thing, even as evidence to the contrary began to pile up.

IPIECA went from being a project of UNEP’s Industry Programme to securing consultative status as its own separate non-governmental organization in 1995. It has been at every COP and functions, in its words, as the “the oil and gas industry’s principal channel of communication with the United Nations (UN) for environmental and social issues.” In 2002, it changed its name to just “Ipieca”.

Today Ipieca presents itself as a “non-lobby” group that fills an observer role in international meetings, but this contradicts how the organization has long understood its own activities. In 2006, when the IPCC proposed limiting the role of observer organizations like Ipieca in climate negotiations, Ipieca objected to these changes, saying it had long been an “active participant” in the process, including helping to draft climate reports.

“IPIECA has been an observer of, and active participant in, IPCC since the First Assessment Report, supplying authors and reviewers for IPCC reports and experts for IPCC meetings. We are one of the very few NGOs that regularly sends observers to IPCC plenary sessions,” it said.

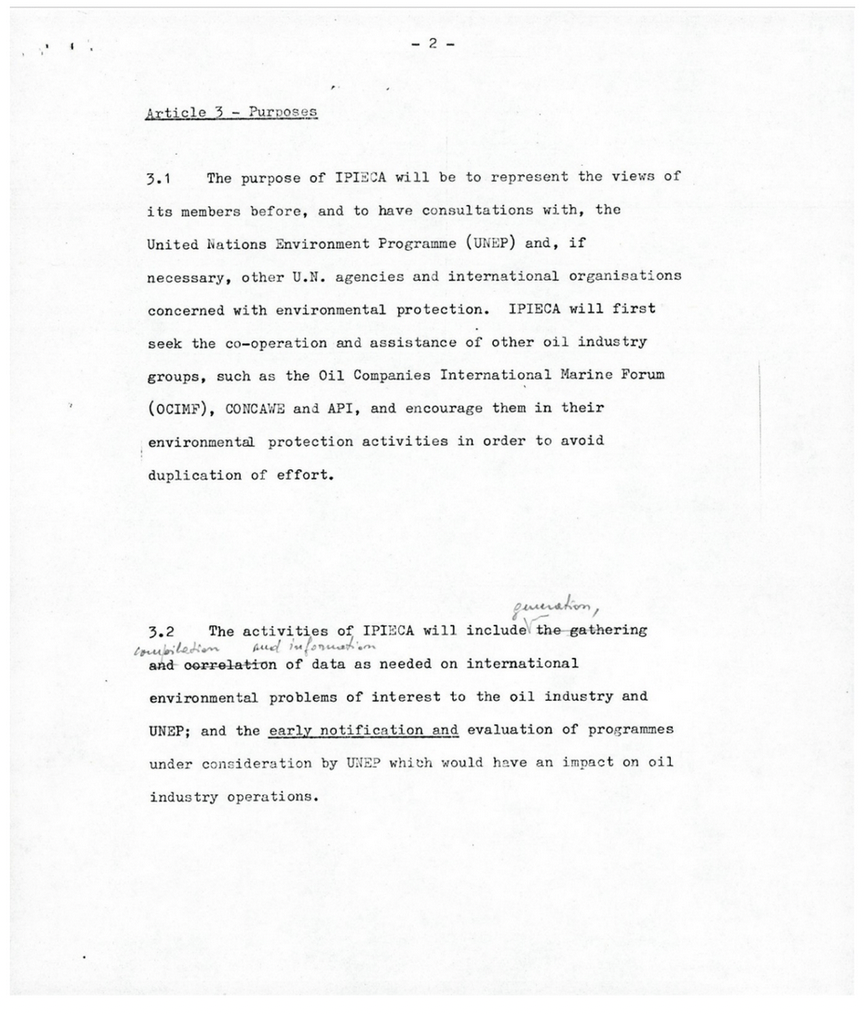

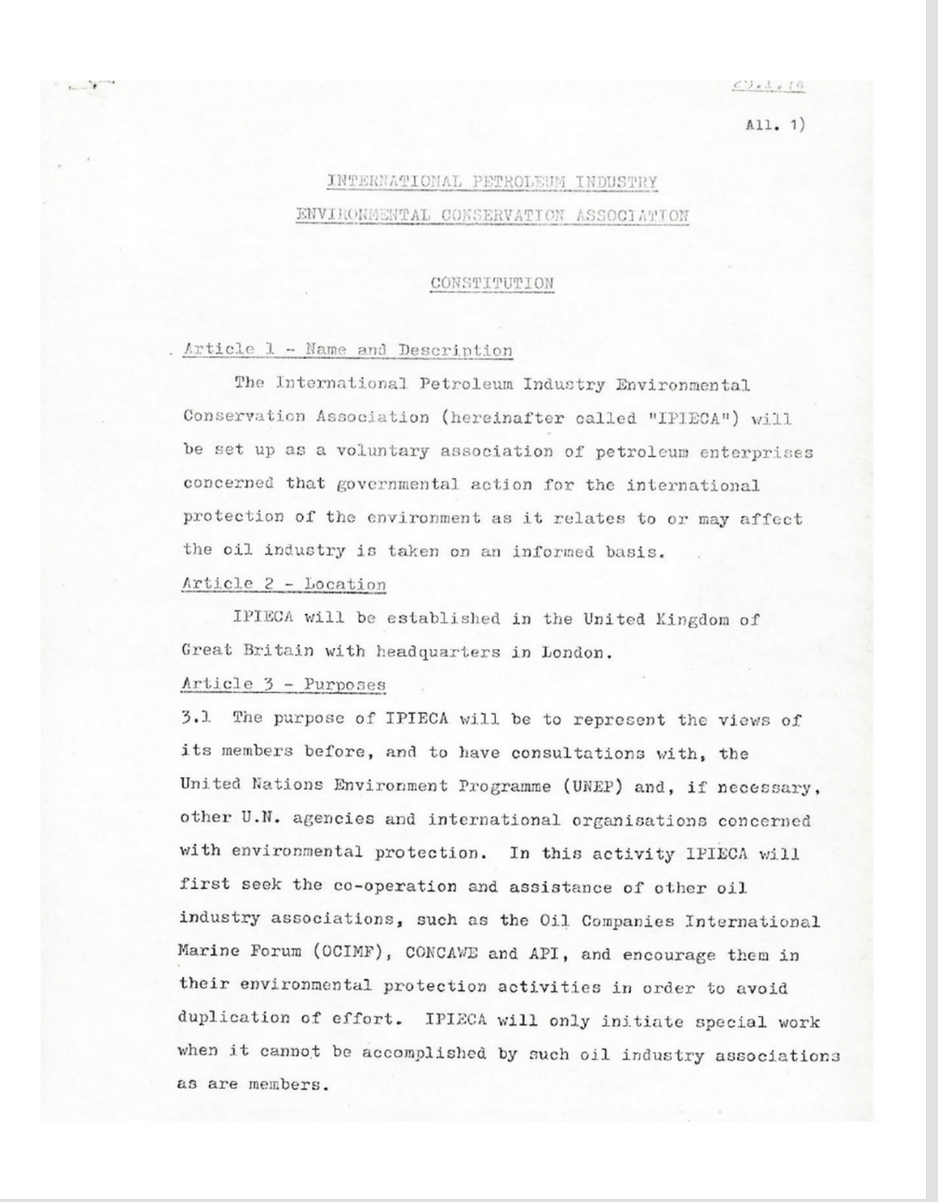

This “active role” is consistent with the organization’s activities from the time of its creation, where it has helped to set the global regulatory agenda on environment and climate issues. Although Ipieca has organized meetings, working groups and industry-wide protocols for events like oil spills, documents emphasize the organization’s role in strategizing around international environmental policy to ensure the least negative financial impact on the industry. In its organizing articles, Ipieca notes that its purpose is both to gather data and information on global environmental issues of interest to the industry and UNEP and for the UN to give the industry a heads-up on pending regulatory shifts, via “early notification and evaluation of programmes under consideration by UNEP which would have an impact on oil industry operations.” In its original constitution, Ipieca describes itself as “a voluntary association of petroleum enterprises concerned that governmental action for the international protection of the environment as it relates to or may affect the oil industry is taken on an informed basis.”

Ipieca organizing documents from the ENI archive, retrieved by Greenpeace Italy.

In a study published November 2021 in the journal Global Environmental Change, researchers Christophe Bonneuil at the Centre de Recherches Historiques in Paris, Pierre-Louis Choquet at the Centre de Sociologie des Organisations at SciencesPo in Paris, and Ben Franta at the University of Oxford confirmed via interviews with Bernard Tramier, a former executive with France’s state-owned oil company Elf (which has since been absorbed by Total Energies) and former Exxon scientist Brian Flannery that it was through Ipieca that Exxon initially briefed the industry in 1984 on the issue of global warming, at a meeting held in Houston.

Tramier described the meeting as the first time he had heard about the seriousness of the problem and what it might mean for the global fossil fuel industry.

“The moment I remember really being alerted to the seriousness of global warming was at an IPIECA meeting in Houston in 1984,” Tramier told Bonneuil. (Flannery later confirmed the existence of said meeting.) “There were representatives from most of the big companies in the world there, and the people from Exxon got us up to speed. […] They had remained very discreet about their own research [on global warming] […] Then in 1984, perhaps because the stakes seemed to have become too great and a collective response from the profession required, they shared their concerns with the other companies.”

From this moment, Ipieca’s role began to evolve. For years the organization, operating under the auspices of the United Nations, was a rich source of intelligence for industry. But it offered another benefit: access. Those carrying an Ipieca badge could attend global meetings of world governments without having to identify themselves as working for a particular oil company, enabling industry to interact with environment ministers and other global leaders in a less formal way.

This was a concept Strong embedded early on, not just in the official workings of UNEP but in his approach to getting things done, which notoriously leaned on informal, off-the-record meetings to ensure that official events ran smoothly. It was not uncommon for Strong to host a casual ski weekend, for example, bringing together government ministers, think tank heads, and CEOs to hash out important world issues during an après-ski session.

These tactics may have been effective at securing diplomatic buy-in, but they also prompted criticism from the left of Strong’s personal relationship with those they saw as being responsible for the worst environmental problems, and outlandish conspiracies on the right alleging he was engaged in a global conspiracy to subvert property rights and usher in global communism.

Strong’s diplomatic instincts however, and naive faith in business leaders to do the right thing when called upon, meant that fossil fuel producers and their representatives were often included in decision making processes. Franta said it is important to understand that “from the very beginning” of international efforts to address climate change, “the oil industry was right there”.

“There’s never really been a time when there was a pure understanding of climate change that was unpolluted by the industry’s interference and involvement and influence,” Franta said. “Our whole understanding of the issue, from the very beginning – and by our, I mean ‘the world’ and by ‘the issue’, I mean ‘global warming’, was influenced by the oil and gas industry and the fossil fuel industry in general.”

“Ipieca fits into that because, again, the industry did this by having this sort of veneer of credibility on the issue that they could use to insert themselves into organizations like UN processes and influence them.”

The combination of intel, access and reach meant Ipieca could marshall the resources of trade groups, industry associations and individual companies across the globe to ensure they were all on the same page.

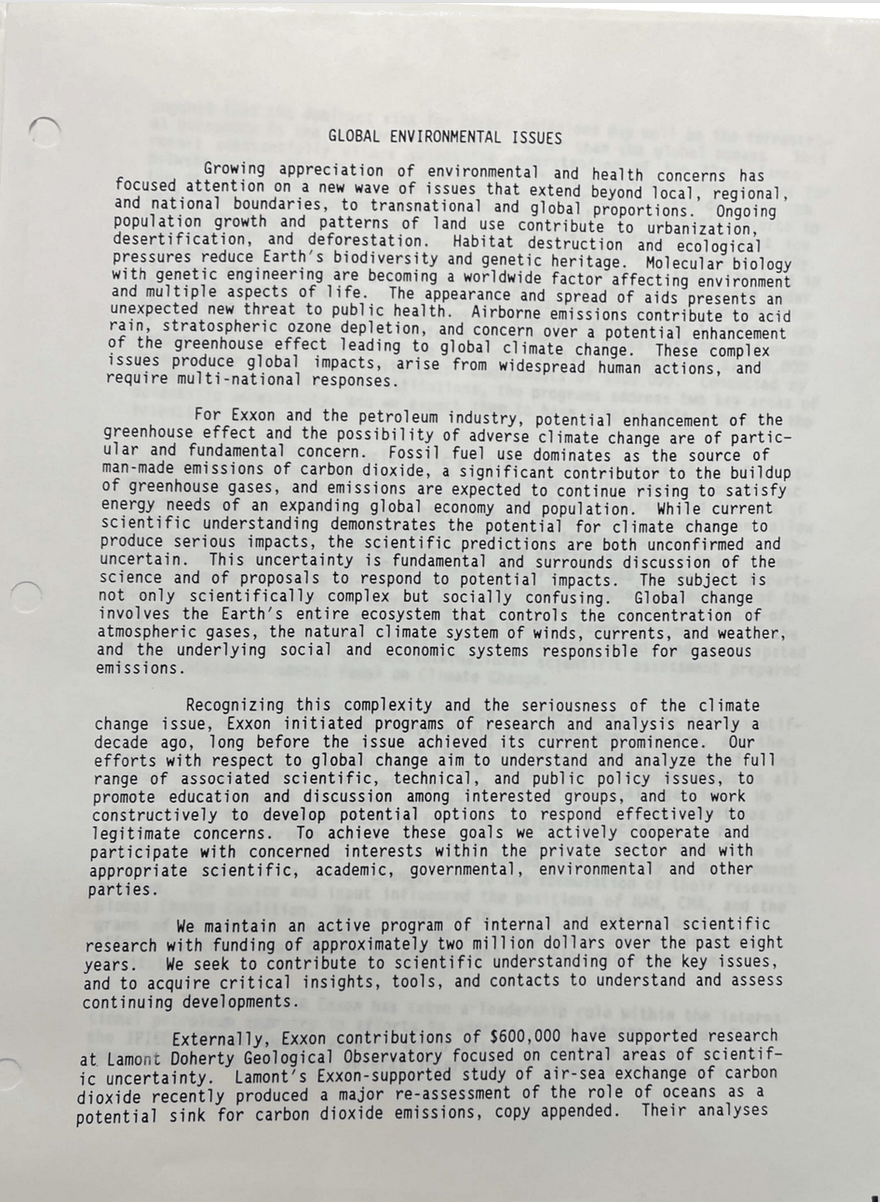

A 1991 internal report outlining Exxon’s leadership on the issue of “global change,” appended to a copy of a 1989 presentation of what the company knew so far about the “potential enhanced greenhouse effect,” highlights Exxon’s leadership role on climate in particular within Ipieca. “Through our expertise and long standing contacts, Exxon has taken the lead in the past year to develop a program of larger scale research, supported under the aegis of the International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association (IPIECA),” the report read. “ ...Through IPIECA Exxon has taken a leadership role within the international petroleum industry in efforts to address global change. Exxon chairs the Ipieca Global Change Working Group which coordinates activities and interactions. We organized several international symposia for education and dialog between key figures in the international public policy debate and representatives of industry.”

The report also detailed Exxon’s role in shaping various other industry organizations’ understanding of and response to climate change. “Exxon's long term public presence and contributions to the scientific field give us unique credibility within the petroleum industry, and the larger private sector,” it read.

“We use that capability to contribute to education and debate on global change within the private sector, and as a major focus in all discussions of public policy with private and governmental agencies. We provided briefings to management committees and major operating committees of the Chemical Manufacturers Association, the National Association of Manufacturers, and the American Petroleum Institute. We served on the task force of the American Petroleum Institute, and contributed significantly to development of the API position on global change, and to the formulation of their research program. Our advice and input influenced the positions of NAM, CMA and the Global Change Coalition [Global Climate Coalition]. We are engaged in several efforts to develop programs of scientific research supported by the private sector, including efforts by the Global Change Coalition [Global Climate Coalition] and the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI).”

Over and over again, the report emphasized the point of Exxon engaging in all of these activities:

“Through many avenues, including technical and scientific interchanges, and through trade associations and Ipieca, Exxon works with organizations involved in shaping the public policy response to global change,” he wrote. “These contacts allow us to maintain awareness of public policy developments, and to contribute input from the petroleum industry.”

Cover letter of 1991 report on Exxon’s approach to “global change,” retrieved from the Briscoe Archive at University of Texas at Austin by Amy Westervelt in 2020.

Maurice Strong left UNEP in 1975, spent two years running Canada’s national oil company, PetroCanada, did a stint running a Denver-based oil promoter called AZL Resources, then helmed a controversial bid to privatize Colorado water. By 1991, when the Exxon report was published, he had returned to the UN as head of the UN Conference on Environment and Development, which came to be known as the Rio Earth Summit. Conversations were underway for planning that event—not just with various politicians, but this time directly with industry as well, particularly through Ipieca and the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC).

In a December 1990 strategy memo about how to amplify its newly adopted Sustainable Development Charter, the ICC notes that “certain specialized business organizations with which the ICC has close relations— for example CEFIC (chemicals), IPIECA (oil) and IPAI (aluminum)” would be briefing their member companies. The memo states that the group would be getting “special support” from Dr. Stephan Schmidheiny, who they described as “the leading Swiss industrialist”; today, Schmidheiny is serving a 12-year prison sentence for aggravated manslaughter in Italy after his company poisoned an entire town with asbestos waste. In 1990, though, the asbestos tycoon had been recently appointed as Principal Business Adviser to Maurice Strong at UNCED. Schmidheiny was also a Vice-Chairman of the ICC Commission at the time and a member of the Board of the ICC's International Environmental Bureau. In 1990, he began creating a 'Business Council on Sustainable Development,’ which the ICC described as “comprising some 40 leading chief executives known for their Interests in environmental matters.”

Stockholm had shocked the industry by locking it out. But for the Rio conference, Strong included industry as co-planners. He would later chastise world leaders for not making a strong enough commitment at the Summit, bitterly telling The Washington Post, “we have agreement without sufficient commitment.”

“When we thought we did it in Stockholm, we didn’t,” Strong said. ”And we don't have another 20 years now. I believe we are on the road to tragedy. As we leave Rio, we have not satisfied that concern. We have the basis for progress, but we have to push ahead."

The world would get another chance a few years later for a Stockholm-esque moment with the 1997 COP in Kyoto, where several world leaders were committed to signing on to binding emissions reductions. Once again, Exxon executives pulled together an Ipieca symposium, this time laying the groundwork for an economic argument against acting on climate change. In talk after talk, government and university economists presented their thoughts on whether the economic impact of acting or not acting on climate change was worse.

“Concern was expressed over how the negotiations are being carried out,” a report summarizing the late 1996 meeting reads. “Much of the negotiations are being handled by environmental ministries while there may be large economic costs of lowering CO2 emissions. …The meeting closed with the comment that it is more important to get the decision right than to rush to an agreement at Kyoto.”

The agreement to curb emissions made in the Kyoto Protocol was dead on arrival in the U.S., thanks to the preemptive Byrd-Hagel resolution, which leaned on exactly the types of arguments put forward by industry interests at the Ipieca symposium.

As COP 29 wraps up in Baku, we are once again hearing these arguments. Some COP negotiators, Christiana Figueres included, have come to the realization that industry will never act in good faith on climate, yet also see their sanctioned presence at COP as a moot point. Figueres noted recently on her podcast that whether oil executives are at COP or not has little to do with their influence over government negotiators; that influence exists, she said, whether executives are physically present and having meetings around the COP negotiations or not. She has, however, joined calls for requirements that the host country at least be supportive of climate policy.

As Ipieca turns 50 and COP rounds the corner to 30, perhaps it’s time to try one more meeting like Stockholm, without CEOs invited to the party.

Anna Pujol-Mazzini and Karen Savage also contributed reporting to this article. Additional documents were contributed by Dr Marc Hudson. ENI documents were provided by Greenpeace Italy.