This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

In August 2019, Dr. Brian Fisher stood before a room full of fellow economists to deliver a lecture at the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy where he explained how, had he led the country’s climate change negotiating team in Paris, he would have made sure Australia had continued to do the bare minimum.

Fisher is a storied figure within Australian public service and political life whose sway over the country’s climate change policy stretches back three decades. His view, broadly speaking, was that there were good solutions and bad solutions for addressing climate change, but over the last three decades of IPCC processes, the world had consistently pursued the wrong ones. As an economist he considered the complicated mess of targets and pledges that emerged from the COP process to be economically irrational, costly, unworkable and most of all unjust.

He outlined these views in his 2019 presentation: “Any chance Australia will ever see the use of first best climate and energy policy instruments?” It was an ironic title for the talk given the role he played in rendering Australia a dissembling mess on climate change. With his wide-ranging summary of his understanding of international climate negotiations up through the late nineties and middle 2000s out of the way, Fisher then turned to his subject: The Paris Climate Agreement. Under the treaty signed in 2015, Australia had pledged an emissions reduction target of 26% – half what the U.S. pledged, but still far above what Fisher would have recommended.

“Everybody can choose their own target,” he said. “So if you are brave enough, had I been the negotiator for Australia for the Paris Agreement, I probably wouldn’t have gone for 26%. I would have been brazen and horrid and gone for 10% just because I’m a nasty person.”

His comments were based on an analysis he had run using the same economic models he had been developing since the early nineties. They also came at a time when Fisher found himself steeped in controversy. A few months earlier, the 2019 federal election had returned the conservative Liberal Party to power under the leadership of Scott Morrison, whose government would be decidedly pro-gas. Fisher had personally intervened in the election campaign when he published a summary of his modelling analysis – but not the full detail – that alleged a plan by the Labor opposition to address climate change may cost the Australian economy hundreds of billions of dollars.

His conclusions generated screaming headlines around the country, even as his work, when the full detail was finally published, was roundly criticized for its heroic assumptions and exaggerated conclusions. Some of those critics were in the audience for his August talk, and they heckled Fisher, asking how his work had wound up on the front page of the only national broadsheet newspaper in the country at a critical moment in the election. Fisher claimed he had no idea, but documents later obtained under Freedom of Information and shared with The Saturday Paper show Fisher had worked closely with the office of then energy minister Angus Taylor. Later, he would be hired by the re-elected Coalition government to help review government modelling on climate change.

The episode could be considered emblematic of Fisher’s career and the shadow he has cast over Australian climate policy for three decades. He started out as an agricultural economist – his PhD thesis, published in 1977, was titled, “An analysis of storage policies for the Australian wheat industry” – and the first decades of his working life were spent teaching within universities before joining the public service in 1988 to head up a newly created agency, the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics (ABARE, pronounced “A-BEAR”).

The position gave Fisher influence and reach at a time when the world was shifting around him. The first attempt to use economic modelling to influence government thinking on climate change in Australia had taken place in 1989 when a group of academics and consultants, including economists with the Melbourne University Institute of Applied Economics and Social Research working with an economic model called ORANI, were hired by resource company CRA to assess the implications of a plan to reduce emissions 20% by 2005. CRA, later renamed Rio Tinto in 1997 after a merger, was a producer of coal and uranium.

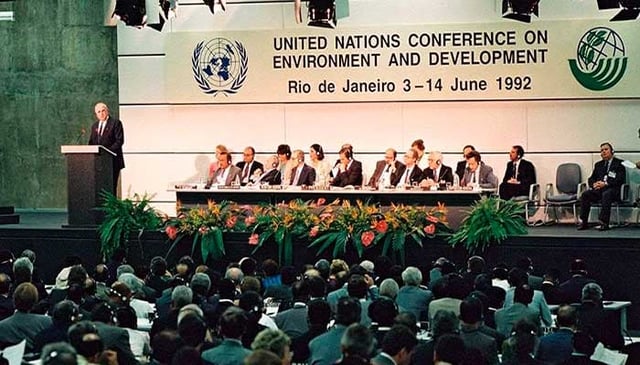

A few years later, interest in economic models that could help determine the costs associated with addressing climate change grew amidst a flurry of lobbying activity by Australian business in the wake of the 1992 Rio Earth Summit. Under Fisher’s leadership, ABARE would develop its own model for understanding the economic impact of climate policies – a capability that proved so valuable Fisher later ensured that the modelling team were housed on the top floor of the agency’s building, within meters of his office.

ABARE had already undertaken some research on climate change prior to the Rio conference and in March 1993, work began on a model called“MEGABARE”, with input from the firm ACIL Economics. In essence, the work involved creating a sprawling spreadsheet that represented an abstraction of the Australian economy and could be used to run simulations about what certain policies might do. The results could even be expressed in dollar terms.

“It was maddening,” Clive Hamilton said. “No one bothered to challenge it.”

Hamilton, an Australian author and public intellectual, was an early critic of Fisher’s work who says the economist’s close association with industry was “no secret.”

“He hung with those people as if they were his tribe,” he said. “That’s what offended me. My father was in the public service his whole life and I absorbed the view that public servants should be independent, because that’s what they get paid to be.”

“To see Fisher out hobnobbing with the most serious coal and petroleum lobbyists was offensive.”

Fisher’s pitch for MEGABARE happened to coincide with growing demands by the Australian government for agencies like ABARE and other scientific bodies to seek a larger share of their funding from external sources. In 1993, ABARE was required to seek 30% of its funding from the private sector, a figure that would rise to 40% by 1998. From the outset, Fisher planned to secure half of the seed funding to develop MEGABARE from private industry, and would enlist the help of the Business Council of Australia (BCA) to raise the money.

It was an attractive proposal. The organization, which counts Australia’s largest companies among its membership, lobbied hard ahead of the 1992 Rio Earth Summit “to ensure that international agreements must be implemented in the context of Australia’s domestic economic circumstances”. Afterwards, when governments had rolled back ambitious calls for action under the Toronto Agreement and placed business at the heart of broader negotiations on climate and environmental issues, the BCA mobilized to take advantage.

Copies of BCA’s newsletter from 1993, found by climate transitions scholar Dr. Marc Hudson provide a window into this frenzied period of activity undertaken by Australia’s business community in response to government concern about climate change.

“It is very much about trying to secure the victory after Rio,” Hudson said. “By 1992, they knew climate change as an issue was not going away, so they were getting ready in preparation for another fight.

“They did not know how long it would take. They thought it would take four, five years. In the end, it was less.”

The BCA newsletter reveals how the Australian government asked the organization to help cover the cost of sending representatives from 65 of its member companies to attend international and climate treaty negotiations as part of the Australian delegation. The Business Council leapt at the opportunity for direct access, reporting to its membership in 1993 that this was a chance to influence international negotiations on climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and deforestation – one that its counterparts overseas had not yet realized.

“The Australian Government has permitted business NGOs to be represented in official delegations negotiating these agreements – together with conservation NGOs,” it said. “This is a rare opportunity – Canada and the US have only recently followed suit and very few other countries permit direct participation by NGOs, whether business or conservation groups.”

The BCA told its membership this was critical to maintain momentum after Rio to ensure they “can legitimately affect the agenda of those [future] negotiations which have clear potential to impact on all aspects of Australia’s competitiveness.”

At a time when the international architecture for dealing with climate change and the world’s biggest environmental challenges had just been created and “the cement is wet”, Hudson said these organizations saw an opportunity to be in the room, helping shape foundational “rules of procedure and protocol”.

“If you can shape the norms, the legal and regulatory and cultural norms, in ways that benefit you in the immediate aftermath of a global treaty being signed, you make your life much easier in the long term because things are going to turn out the way you want without having to fight a pitched battle,” he said.

To aid in this, BCA organized a workshop in September that year for business leaders, with the final presentation delivered by John Daly of ACIL Economics, the same consultancy that had been assisting Fisher to develop a proposal for ABARE’s model.

It was that year Fisher appeared to make his pitch to the Australian oil and gas industry to fund ABARE’s modelling work. At the national conference of the country’s oldest oil and gas industry association, the Australian Petroleum Exploration Association (later renamed the “Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association” and today known as “Australian Energy Producers”) he and his team presented a paper that sought to show economic language could be a tool for industry. The paper, “Sustainable Development and Exploration”, rested on the assumption that markets were always the most efficient optimizers. It argued that, when working out whether to conserve the environment, oil and gas exploration was always a net positive as it allowed a company to obtain information that would determine whether it should proceed to more intensive work. If the company chose not to go ahead because the potential return wasn’t worth the effort, Fisher and his co-authors argued, this could be thought of as an act of conservation.

“A commercial decision not to exploit a site, in fact, is also a decision to conserve environmental values at that site,” it said.

This idea – that a lack of information stopped the market from making the most efficient and best decision on any given issue – was at the heart of Fisher’s economic ideology and basic pitch to industry. Elsewhere in the paper, he used climate change to illustrate how this uncertainty made it hard to know how to act.

“While it may be possible to determine the extent of greenhouse gas emissions resulting from a given level and mix of economic activity, the effect of those emissions on the level and mix of future economic activity is difficult to ascertain,” it said.

Fisher would suggest a solution: modelling. With MEGABARE, Fisher wasn’t just promising better numbers. Like a fortune teller he was offering to reach into the future using his numbers in an effort to predict outcomes. Richard Denniss, Executive Director of The Australia Institute, said the illusory certainty he offered had a profound effect on Australian politics.

“William Nordhaus is far more recognised for all this stuff, but Brian woke up every day and did the work,” Denniss said. “He showed industry groups how to argue – the idea that acting on climate change is bad for the economy is very Nordhaus. Brian came along and was like, ‘let me put the decimal place in a dollar figure for how bad a carbon tax will be.’”

For almost the entirety of his career, Denniss said, Fisher’s work has focused almost exclusively on the cost of transition rather than the cost of inaction or the potential benefits of moving away from fossil fuels – a matter of emphasis that has uniformly benefited industry and fossil fuel producers in particular.

Hudson said the available evidence “shows there was an extremely determined, well thought-out and well-financed effort to create the perception that climate action would be incredibly costly”. This effort sought to “cast sensible, preventative or proactive action on climate change as irresponsible.”

“These people were working together to create an economic model that they can use to create reports with headline statistics saying economic output will fall by x percent if we undertake a particular policy,” he said. “Then these economic reports are released at strategic moments before a government report or announcement. These headline figures are repeated in parliament or in newspaper columns and they become accepted as ‘common sense’ among politicians.”

According to Ben Franta, head of the Climate Litigation Lab at the University of Oxford, on a global scale, the work of Fisher and other economists fit into a wider mobilization by industry as it campaigned to defend itself from attempts to end fossil fuel extraction.

“I call this the twin thread of obstructionism: the science denial, and then the weaponization of economics” Franta said.

“Since the 1950s, climate scientists have been warning us about this problem and the science has been clear enough to take action, and many of the predictions have been quite accurate and have been materializing.

“But the economists often said, ‘don't do anything about it,’ because the whole problem conflicted with their ideology – the ideology being that the market will correct any problems that might arise by definition, and if the market doesn't correct those problems, then they're not really problems.”

As a major fossil fuel producing country, Australia has always viewed climate change through what it means for its oil, gas and coal exports – an institutional arrangement that guaranteed Fisher and ABARE an attentive audience. A 1998 investigation by the federal Ombudsman into the creation of the MEGABARE, and its successor model GIGABARE, found that fossil fuel producers were involved at every stage of its creation.

At the outset, the agency set up what it called a “steering committee” with a membership fee of $50k – a hefty sum for environment groups, but easily justified by individual companies and their industry associations increasingly concerned about how government might respond to climate change. The first to sign up was the Australian Coal Association in 1993. Later, other companies directly involved in fossil fuel production or industry associations representing fossil fuel interests signed on, including the Business Council of Australia, the Australian Aluminium Council, BHP, Exxon, Mobil and Texaco. The 1998 Ombudsman investigation didn’t inquire about the validity of the modelling, but did investigate this pay-to-play model and found it led to “the possible creation of an expectation of membership influence on issues affecting public policy”.

Throughout all this time, Fisher had given a growing amount of his attention to working directly on climate issues. In 1993, he was appointed Convening Lead Author in Working Group III of the IPCC’s second assessment report. The result, Chapter 11, investigated the use of economic modelling to assess policies for combating climate change.

This likely brought Fisher into contact with W. David Montgomery, an economist with Charles River Associates, who was lead author on a chapter looking at mitigation. Montgomery had conducted economic studies commissioned by the American Petroleum Institute in the U.S., showing results very much in keeping with Fisher's work, specifically that a carbon tax would be more damaging to the economy than climate impacts. The pair would orbit each other throughout their careers, regularly speaking on panels together. Much later in life, after Fisher had left the public service, he joined Charles River Associates as a consultant.

It was in the lead up to Kyoto, however, that Fisher began to grow more active in his advocacy outside of Australia. In 1996, for instance, he attended a symposium in Paris organized by Ipieca, the representative body for the global oil industry within the United Nations, in his capacity as head of ABARE. The symposium, organized by Exxon’s Brian Flannery, sought to bring together “economists, scientists, business executives and analysts with delegates” to review and discuss the “economics of climate change”, focus attention on “key areas of uncertainty” and highlight the “consequences and trade-offs involved in policy choices that could affect economic development, employment, trade, investment, energy security and national sovereignty.”

Alongside Montgomery, Fisher presented a paper titled “Effects of Greenhouse Gas Abatement in OECD Countries on Developing Countries” and participated in a panel discussion where he was trusted to present the Australian view on the best way to tackle climate change. Relying on his model, MEGABARE, Fisher broadly attacked the idea that developed countries might have an obligation to decarbonise first owing to their historical reliance on fossil fuels and suggested that these efforts might actually harm developing world economies.

The idea that responding to climate change would be costly and harmful to developing economies was a line of thought Fisher would continue to develop. In 1997, he appeared alongside Montgomery on a panel hosted by the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a thinktank affiliated with the Atlas Network, a global network of more than 500 libertarian think tanks with a decades-long relationship with extractive industries. Fisher, who warned of “massive income transfers” associated with transitioning away from fossil fuels and used the opportunity to flog a book outlining his analysis using MEGABARE for AUD$36 (AUD$72 or USD$46 in 2024 dollars), was lauded by Montgomery. Charles River Associates had been working to “understand what are the actual economic implications of the negotiating process for the developing countries as well as for advanced economies that are being asked to undertake limits on emissions,” Montgomery said.

“And Brian Fisher at ABARE has been one of the leaders in addressing this set of questions,” he said.

That same year Fisher also presented a paper to the annual APPEA conference titled, “The Economic Implications of International Climate Change Policy” and another paper with the title, “The Economic Impact of uniform emission abatement” to the Countdown to Kyoto conference.

According to a leaked strategy document produced by climate denier and rightwing activist Ray Evans, then employed by Western Mining Corporation, the purpose of the conference was to counter perceived “pro-green views” in the media at the time and to promote “anti-greenhouse science” by presenting conference attendees as “mainstream” The conference was organised by the APEC Study Centre at RMIT University, whose chair, Alan Oxley, was a climate skeptic who argued that action to address climate change would harm the economy, and in secret partnership with the newly-formed American think tank, the Frontiers of Freedom Institute – another Atlas-affiliated think tank. The gathering was co-chaired by Hugh Morgan of Western Mining Corporation and a major Liberal Party donor, and attended by deputy prime minister Tim Fischer and US Senator Chuck Hagel. Both the Competitive Enterprise Institute and Frontiers of Freedom Institute have received funding from Exxon Mobil. Both Morgan and the late Evans maintained an association with the Atlas network.

Even as Fisher increasingly participated in advocacy, the Australian government increasingly relied on his input. He served as a member of Australia’s climate change negotiating team between 1996 and 2001, and in an interview with reporters from the Australian state broadcaster’s flagship investigative program, Four Corners, then-foreign minister Alexander Downer said he relied on ABARE’s modelling. When asked about a challenge to Fisher’s work by 131 economists alleging that it overestimated costs and underestimated the benefits of reducing emissions, Downer was dismissive.

“There are tens of thousands of economists in the world and I could guarantee you I could get them .. get a group of them to sign up to almost anything, as you would well know,” he said.

It was during this period that Australia, a major exporter of coal and, later, gas, would infamously refuse to ratify the Kyoto Protocol but Fisher continued on. In 2003, he delivered another co-authored paper at that year’s APPEA conference in which he explicitly outlined his vision for how international agreements on climate change should take place that relied heavily on technology to solve a political problem.

By 2006, however, the landscape had shifted. Conservative prime minister John Howard was about to lose office and Fisher himself would soon go private. On the way out the door, Fisher took his model with him. The week before he left, he authorized MEGABARE to be made public. He continued to rely upon it in his new career as a consultant, including a two-year stint as Vice President, International at Charles River Associates.

The model – Fisher’s model – had given him everything. It gave him his career, took him around the world, offered profound influence and access to power by virtue of his place adjacent to power. He reportedly met his future wife, Kerri Hartland through his work for ABARE. As of 2024, Hartland serves as the Director-General of Australia’s equivalent to the CIA, the Australian Secret Intelligence Service.

Looking back, Richard Denniss said Fisher’s impact was transformative for the way he pioneered the use of economic modelling as a political cudgel to be taken up by the powerful.

“If Brian had dedicated his life to saying we need to increase unemployment benefits, he wouldn’t have gotten anywhere,” Denniss said. “And that’s what people don’t see about economics. The job of economics in public debate is to dress up self-interest as national interest.”

“He invented the idea that you could put numbers to how silly it would be to tackle climate change, and he led the world in quantifying the costs of climate action, when we should be obsessed with the cost of climate inaction.

“He really changed the world.”

Amy Westervelt and Dr Marc Hudson contributed documents to this reporting. Drilled contacted Dr Brian Fisher through his publicly listed email address at BAE Economics with detailed questions. He did not respond.