This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

On a crisp fall day in Paris in 1996, about a year before global leaders would convene in Kyoto to commit to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, oil company scientists, lobbyists, government ministers, and economists gathered in the offices of France’s national oil company.

The company, Elf Aquitaine, has since been subsumed by Total Energies. But two decades ago it played host to a gathering that sought to wargame how any international treaty to be signed in Kyoto may impact the global economy.

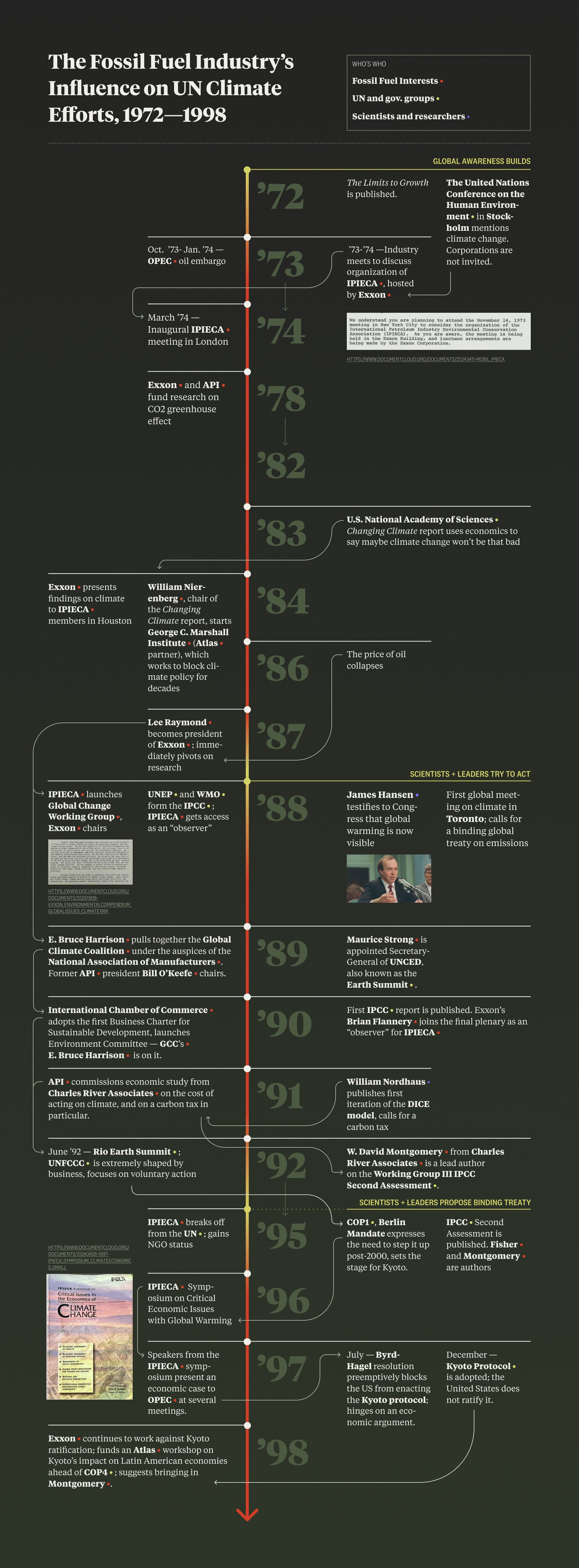

The key organizers of the event were two Exxon staffers—Brian Flannery and Duane LeVine, who had been spearheading Exxon’s approach to climate science—and Klaus R. Kohlhase, head environmental advisor for BP. Their employers were members, along with the rest of the oil and gas industry, of a little-known NGO affiliated with the United Nations Environment Programme called the International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association, or IPIECA. (The group has since changed its name to just Ipieca). According to its website, Ipieca’s role is to act as “the industry's principal channel of engagement with the UN.” Through Ipieca, industry representatives have attended every UN climate negotiation since negotiations began in 1995. It was through Exxon’s membership in Ipieca that Flannery was one of the only industry-affiliated scientists in the room when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change finalized its first report in 1990.

Presenters at the 1996 Ipieca symposium included Brian Fisher, an Australian economist and public servant whose industry-friendly modeling work was funded in part by a steering committee that included Exxon, Mobil, and Texaco; American economist W. David Montgomery, who worked with the firm Charles River Associates and led a 1991 study commissioned by the American Petroleum Institute about how a carbon tax would destroy the global economy; Richard Tol, an economics professor at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and University of Sussex who was later tapped by famed climate skeptic Bjorn Lomborg to try to prove that there is no consensus on climate science; and John Weyant from Stanford University’s Energy Modeling Forum, which boasted a mix of government and industry funders (and continues to), including the American Petroleum Institute, BP, Chevron and Exxon. Sprinkled in amongst them were academics from Yale, Harvard, and MIT, plus a handful of European economists. The audience was a mix of environment ministers who would be charged with negotiating a climate treaty on behalf of their respective countries the following year: lobbyists from groups like the Global Climate Coalition, which represented the interests of various high-emissions industries; experts from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); and other economists.

A report from the symposium, uncovered by Drilled, reveals how the fossil fuel industry handled a critical crossroads in the world’s understanding of the economic implications of climate change that paralleled what was happening in the scientific realm. In the same way that it obscured climate science with research that posited alternative theories for warming, the industry cherry-picked what it liked from economics and sought to make some ideas radioactive to policymakers. This delayed the deployment not just of renewable energy technologies but of economic tools, like a carbon tax, that could have offered the world a smooth off-ramp from the climate crisis.

That 1996 meeting took place at a key inflection point in the economic debate over capitalism and growth. This debate had technically been raging for more than 100 years, but resurfaced in the early 1970s, when early computer modelers at Stanford and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology warned that we were running out of finite resources. Books like Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s “The Population Bomb,” published in the late 1960s, and MIT’s “Limits to Growth,” released in 1972, spurred both alarming headlines and intense backlash.

In the ensuing decades, some of the modelers’ predictions—particularly around population and food shortages—would prove way off. But others—predictions about greenhouse gasses amongst them—were proven to be spot on.

On climate, initially global governments seemed willing to tackle the problem. In 1988, NASA scientist James Hansen testified before the U.S. Congress that climate change was already visible, while the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the key UN intergovernmental body on climate, was also formed. That year, dozens of global leaders also met in Toronto to discuss the climate problem and sign on to The Toronto Agreement, a plan to reduce carbon emissions by 20 percent of their 1988 levels by the year 2000. The prime ministers of Norway and Canada called at the time for a binding international treaty committing to such reductions.

In response, industry mobilized to push the idea of voluntary—rather than mandatory—action. In Australia, Conzinc Riotinto, the mining giant now known just as Rio Tinto, asked economists to use the government’s preferred economic model to map the potential impact of the Toronto targets. The resulting study claimed that “meeting the target could mean electricity tariffs might have to rise by at least 40% in real terms and motor fuel prices by 60-120% to reduce demand sufficiently,” and that it could cost the Australian economy $30 billion. In 1990, as the industry’s observer in the room, Exxon’s Flannery tried to get the IPCC to water down its first report, as a representative of Ipieca, according to Jeremy Leggett’s eyewitness account in his book, The Carbon War.

“Dr Brian Flannery, representing the International Petroleum Industries’ Environmental Conservation Association, but on the payroll of Exxon, took the microphone,” Leggett wrote. “The draft, he reminded the room, said that 60 to 80 percent cuts would be needed in carbon dioxide emissions in order to stabilize atmospheric concentrations of the gas. But this, he felt, required clarification in the light of all the uncertainties about the behavior of carbon in the climate system.”

“Scientists from the UK, Germany and the USA—some of the most eminent climatologists in the world—now spoke. Nobody agreed with Flannery. Of course there were uncertainties, but, if your goal was to stabilize atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, those uncertainties did not undermine the need for deep cuts in emissions.”

Ultimately the IPCC ignored Flannery’s input. Its report acknowledged that climate change was a problem, that burning fossil fuels was the dominant cause of the problem, that the solution was reducing carbon emissions, and that it required global coordination to do so. But the scientific hold on the climate conversation wouldn’t last long.

In 1992, Yale economist William Nordhaus introduced the first “integrated assessment model,” combining economic modeling and climate modeling in the Dynamic Integrated Climate-Economy, or DICE model. As a neoclassical economist and an opponent of the “Limits to Growth” school of thought, Nordhaus tended to take a rather sanguine approach to climate change. For a start, he not only assumed that climate change would impact less than a fifth of the economy, but that there would also be economic benefits to be gained in addition to the potential risk.

This model was welcome news to oil, gas and coal producers who were on the look out for a more optimistic view of the future. But Nordhaus also hit a sour note: among his proposals was a call for a global carbon tax that ran counter to the studies industry had been funding. Research from Montgomery at Charles River Associates, commissioned by the American Petroleum Institute, in the U.S. and from the firm Data Resources Inc (DRI) commissioned by Exxon subsidiary Imperial Oil in Canada claimed the sort of carbon tax necessary to flatten emissions in line with the Toronto agreement would be so high it would tank the economy. Worse, they argued, it would be impossible to deploy fairly across the entire world. That work had been picked up by conservative governments as well. A report released in September of 1991 from George W. Bush’s Department of Energy cited the DRI numbers.

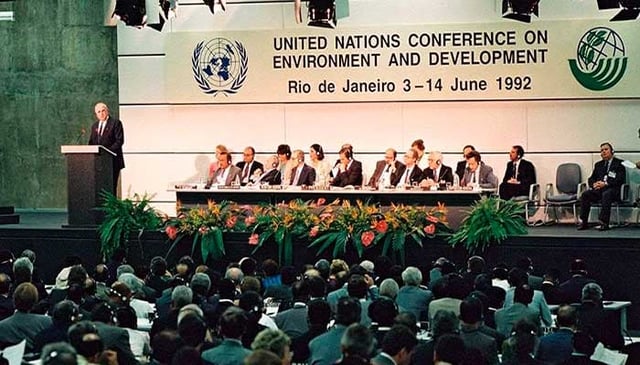

As the media picked up Montgomery’s conclusions and ran with them, industry was deeply involved in the planning for the UN Conference on Environment and Development in 1992, dubbed the “Rio Earth Summit”. The idea was to end the summit with the binding treaty promised after Toronto, but documents from the International Chamber of Commerce and first-hand accounts from Canadian ministers indicate that high emitting industries were able to shape the course of events and ensure that world leaders only committed to voluntary pledges to reduce emissions.

Industry also managed to more fully embed itself into the IPCC process in the early 1990s. When the second IPCC assessment came out in 1995, two economists with deep ties to industry were authors: Montgomery was a principal author on one chapter and a lead author on another, and Fisher was lead author on a chapter entitled “An economic assessment of policy instruments for combatting climate change.” By the time the third report came out, Flannery himself was a lead author. Crisis averted, but not for long.

In March 1995, at the first Conference of the Parties, or COP, global leaders again agreed that there needed to be a binding global climate treaty. They set a deadline of 1997—the Kyoto COP—for signing it. That deadline explains why it was so important for Ipieca to bring everyone together to talk climate and economics in Paris in 1996.

“It was common for these ‘prep-conferences’ to be where all the actual decisions got made” by the industry, Melissa Aronczyk, Rutgers University researcher and author of A Strategic Nature about the history of environmental PR, said. “Then the COP was just the stage version.”

Infographic by EJ Baker, Inkcap Design. Research by Amy Westervelt and Royce Kurmelovs.

At the 1996 meeting, “it’s pretty clear to me that Exxon was getting its ducks in order to go against the Kyoto Protocol. They certainly enlisted virtually everybody in the climate community to attend this conference,” Robert Brulle, an environmental sociologist and professor of environment at Brown University, said.

The idea of a carbon tax was still popular amongst a lot of the economists there, including Nordhaus, who kicked the symposium off by presenting an update to his DICE model. But Fisher, the Australian economist, argued that it was impossible to apply a global carbon tax fairly and claimed that the approach to a treaty going into Kyoto—particularly the requirement that the most developed countries commit to binding emissions reductions first—would fail to actually deliver the emissions reductions necessary long-term.

Montgomery, of Charles River Associates, agreed with Fisher and referenced his own model, the International Impact Assessment Model, created in collaboration with his colleague Paul Bernstein and University of Colorado economist Thomas Rutherford. He used the model to argue that such a treaty would be disastrous for global trade, claiming that “there would be GDP losses not only in the OECD, which incurs the direct cost of reducing emissions, but in all regions.”

History did not look kindly on this analysis. In 2022, Bernstein, Montgomery’s colleague and the model’s co-creator, told University of Oxford researcher Ben Franta that the International Impact Assessment Model was flawed.

“What bothers me is that our analysis just talked about the costs,” Bernstein said.

Nonetheless, Fisher and Montgomery’s argument was echoed repeatedly by the fossil fuel industry in the lead-up to Kyoto. It showed up in an ad campaign the Global Climate Coalition ran in 1997: “it’s not global and it won’t work,” the ad trumpeted about the Kyoto treaty, as ominous music played over footage of sky-high gas prices and expensive groceries.

Shortly after the Paris symposium, Fisher and Montgomery gave a similar presentation at a conference on the “Costs of Kyoto” held by the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a “free-market” think tank with ties to oil magnates Charles and David Koch. In June 1997, Montgomery embedded similar talking points in his testimony to the U.S. Senate during a hearing “to examine current international negotiations intended to curb global greenhouse gas emissions.” The following month the Senate passed the Byrd-Hagel resolution, which preemptively blocked the U.S. from ratifying any treaty that would, “(A) mandate new commitments to limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions for the Annex I Parties [more developed countries] unless the protocol or other agreement also mandates new specific scheduled commitments to limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions for Developing Country Parties within the same compliance period, or (B) would result in serious harm to the economy of the United States.”

Montgomery was a frequent witness at Congressional hearings about Kyoto. He testified at three separate hearings from September 1996 to October 1997. In his last pre-Kyoto appearance he warned lawmakers against trying to reduce emissions “indirectly through regulatory programs, which will make it much more expensive.” He advocated instead for “visible policies like carbon taxes or tradable permits,” but also noted that even these policies would shave 1 percent off GDP and result in massive productivity losses and lower wages.

While the U.S. would go on to sign the Kyoto Protocol later that year, the industry would continue to successfully block the government from ratifying the treaty. In 1998 as world leaders prepared to meet in Argentina for the fourth COP, Exxon funded the Atlas Economic Research Foundation—today known as the Atlas Network, a global network of more than 500 “free market” think tanks—to host a workshop in Buenos Aires on how damaging Kyoto would be for Latin American economies. Exxon public affairs executive Randy Randol sent Atlas staff a report Charles River Associates had published on this very topic, and suggested they bring Montgomery in to speak at the pre-COP workshop.

At the same time, Stanford’s Weyant brought together many of the same presenters from the 1996 Ipieca symposium, Montgomery and Tol included, to contribute to a special issue of The Energy Journal, the academic journal published by the International Association for Energy Economics, entitled “The Costs of the Kyoto Protocol: A Multi-Model Evaluation.” The U.S. Department of Energy, EPA, and the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) were thanked by name for funding both the journal issue and the modeling alongside “about 20 corporate affiliates.” One of those affiliates was Exxon, which also had an employee on the journal’s board of editors.

The Kyoto target was far more modest than the one set in 1988 in Toronto: it asked countries to commit to a 5 percent reduction of 1990 emissions levels by 2012, where Toronto had demanded a 20 percent reduction of 1988 emissions levels by 2000. The Kyoto treaty was nonetheless deemed impossibly damaging to the United States economy and never ratified. A 2001 State Department memo briefing an official for a meeting with the Global Climate Coalition reminded them to let the GCC representatives know: “POTUS rejected Kyoto, in part, based on input from you,” and to ask them for ideas: “interested in hearing from you, what type of international alternatives to Kyoto would you support?”

W. David Montgomery appeared on Capitol Hill again to testify against climate policy and in favor of lifting the country’s export ban on oil and gas from 2011 until the ban was lifted in 2015. Every time, he leaned on his position as a former IPCC author to establish his climate credentials. Much of his work has since been criticized for baking in assumptions that skew the results.

Similarly, Nordhaus has been criticized by several economists for failing to update some of the assumptions in his DICE model to keep pace with climate science and extreme weather realities. A new report from Carbon Tracker, for example, noted that none of the neoclassical economic models embraced by both industry and policymakers account for climate tipping points. Scientists predict that the collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)—the Atlantic Ocean’s main current system—will be catastrophic, for example, reducing the amount of land suitable for growing wheat and corn by a whopping 70 percent. Despite the clear cascading threat to food security that climate change poses, economic studies have tended to brush off AMOC collapse and other tipping points, which don’t fit neatly into existing models, as inconsequential. That could mean major market corrections in the future that cause global instability.

“Each layer in the process of assessing the risks of climate change has assumed that the previous layer has done its job adequately, and has relied upon the previous layer’s reputation, rather than scrutiny of the work undertaken,” an earlier Carbon Tracker report on flawed economic models and their impact on pension fund investments noted. “Pension funds relied upon consultants, because of their reputation in the field; consultants relied upon academic economists, because their papers had passed refereeing [the peer-review process]....the foundational layer in this inverted pyramid of trust—the refereed mainstream economic literature on climate change—did its job extremely badly. Therefore, the work of the layers above—the consultants, the funds, the financial regulators and governments—is also unsound.”

Industry has been happy to use these flawed models to block or promote preferred policies, though. After fighting it for years, ExxonMobil publicly supported the idea of a carbon tax in 2015 and actually lobbied for one in 2017 – two decades after it funded economic research that called the idea into question and lobbied aggressively to render it unviable.

"A lot of years were wasted, in my opinion, trying to come up with this idea of what is the optimal amount of warming, what's the optimal price to put on carbon, as if those things are even tractable problems scientifically,” Ben Franta, founding head of the Climate Litigation Lab at the University of Oxford, said. “This obsession has lasted for decades in lieu of actual solutions, practical solutions, to the problem. And it's still dominant today.”

Ipieca, ExxonMobil, Flannery and Montgomery were all contacted for comment for this piece. None responded by our deadline, but we will update the piece if comment is received.