This story was reported by the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP) and Mongabay Latam, with support from the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting and published as part of the Opaque Carbon journalistic partnership bringing together 13 media outlets from eight countries to probe how the carbon offset market is working in Latin America. It is republished here with their permission. You can also read the original article in Spanish here.

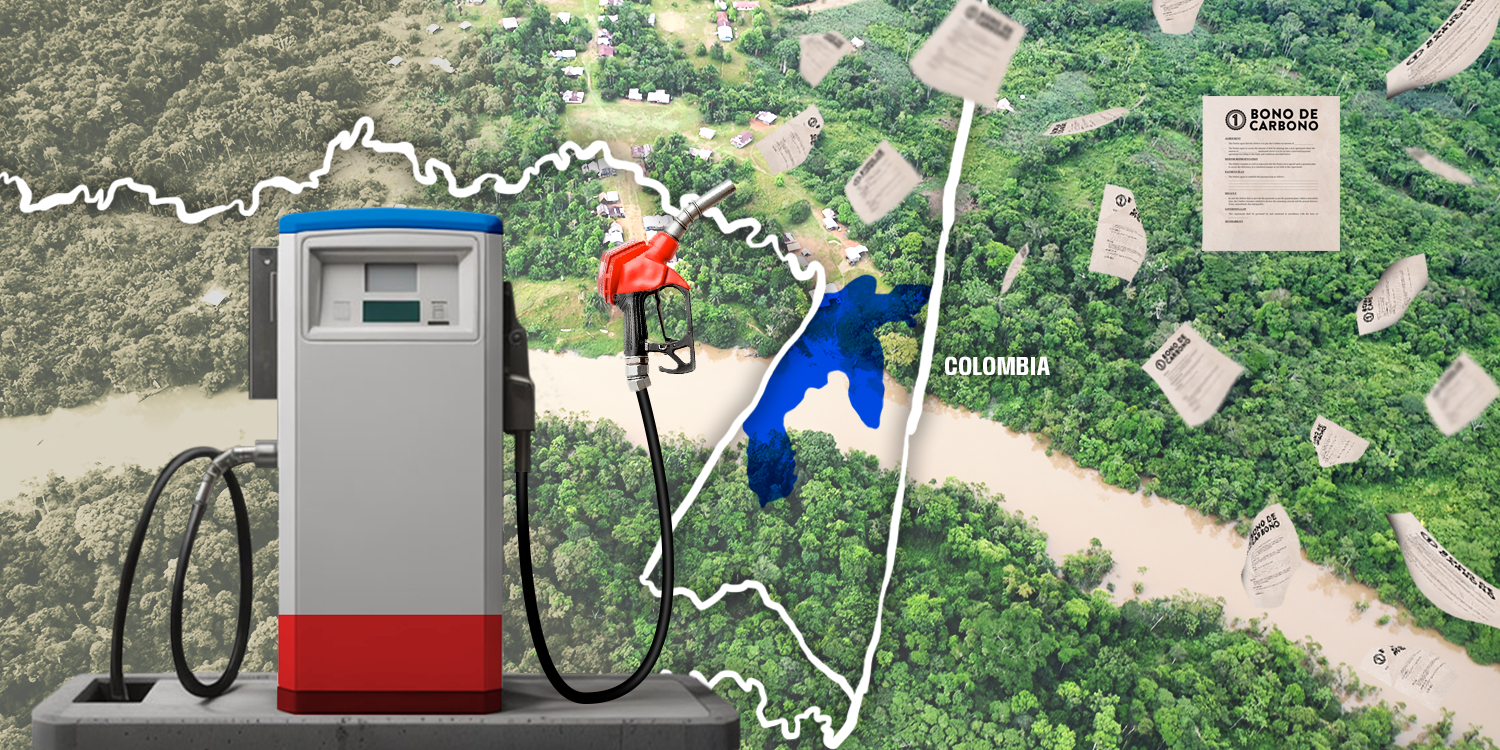

From September 2022 to May 2024, Chevron's Colombian subsidiary bought 3 million carbon credits from an Indigenous community in the Colombian Amazon. Those credits allowed the oil company to offset part of its environmental footprint in Colombia. It used a market mechanism known as REDD+, which puts a value on the conservation efforts of the Cotuhé Putumayo Indigenous reservation, and thus reduced the amount of carbon tax it had to pay to the Colombian government given that its economic activity is highly polluting. Each credit used is equivalent to one ton of carbon dioxide—one of the greenhouse gases driving climate change—that in theory no longer rises into the atmosphere as a result of the tribe’s conservation effort.

It would be good news, save for the fact that members of the Indigenous community hosting the project claim not to know anything about it. Six leaders from the Cotuhé and Putumayo Rivers reservation, located at the top of the small foothills in the extreme south of Colombia, told the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP) that they know nothing about the documents, activities or money raked in by an initiative called 'Preserving the Life of the World, Mowíchina arü Maü, Cotuhé and Putumayo Rivers' supposedly being implemented within their communal land.

This is the second time Chevron has used the environmental efforts of an Indigenous community that claims to be unaware of the project in question to offset its emissions in Colombia. Between October 2022 and June 2024, the oil giant purchased and used 1.1 million carbon credits from the Pachamama Cumbal project amid the Andean high mountain tundras and cloud forests of an Indigenous reservation in southwestern Colombia. Complaints soon arose among the Pasto Indigenous inhabitants of the Greater Cumbal reservation. They claimed to be unaware of the project’s existence, as an investigation by CLIP revealed in June 2023. A group of them took the project to court. Both initial and appeals judges sided with the Pasto, ruling that their fundamental rights had been violated.

Chevron defended itself at the time by saying that it was confident that the project had "permits and approvals from the corresponding Indigenous government authority and also (...) the corresponding socialization processes.” The oil company claimed to have a robust due diligence process to ensure high-quality offsets and promised that "our offsets have a degree of compliance accepted by the governments in the regions where we operate."

Both projects, the one in Cumbal and the one in the Amazon, were developed by the same Mexican company, Global Consulting and Assessment Services S.A. de C.V., assessed by the same auditing firm, Deutsche Certification Body S.A.S., and authorized to enter the carbon market by the same certifying standard, ColCX. While the relationship between developers and auditors should be independent and impartial, CLIP uncovered that Global Consulting's CEO was a founding partner of Deutsche Certification Body. In other words, the company where she now works hired her former firm to audit her project, creating a potential conflict of interest for both companies.

Despite these companies’ track records, Chevron Petroleum Company—a subsidiary of Chevron Global Energy Inc. in Colombia and owner of 460 Texaco-brand gasoline stations in the country—once again bought credits from a project in which they were involved. At least 1.3 million credits bought by Chevron from the Amazon-based project were used after judges halted the Cumbal project.

This is the main finding of this new investigation by the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP) and Mongabay Latam, with support from the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting and published in partnership with Drilled. It is part of the Opaque Carbon journalistic partnership, which brings together 13 media outlets from eight countries to probe how the carbon offset market is working in Latin America.

Chevron used almost one million of these credits from the Amazon after the entity that oversees all auditors in Colombia suspended Deutsche Certification Body's accreditation. In total, the oil giant bought 1.8 million credits after journalistic revelations made the issues with Global Consulting’s Andean initiative clear. The oil company argues that at no time did the project in the Amazon report any problems and that Global Consulting told it that the Indigenous authorities denied that there was a conflict in the reservation, although it clarified that it now no longer has any commercial relationship with the developer.

These findings raise serious questions about the due diligence standards at one of the largest fossil fuel companies in the world. They show that, even though the REDD+ mechanism promised to be an innovative financial solution linking companies seeking to pay to offset their carbon footprint with local communities caring for strategic forests to mitigate the global climate crisis, in some cases these communities are not benefiting from such arrangements.

The Cotuhé and Putumayo Rivers Indigenous reservation, crossed by the Cotuhé River seen here, is home to 945 square miles of Amazon rainforest in a very high state of conservation. Photo courtesy of Rodrigo Botero / Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development (FCDS).

A 100-year project in the Amazonian trapeze

In September 2022, the Colombian certifying standard ColCX approved the REDD+ project Conservando la Vida del Mundo, 'Mowíchina arü Maü, Ríos Cotuhé y Putumayo, described on its public registry as "an initiative of the indigenous Tikuna inhabitants of the Cotuhé and Putumayo Rivers reservation, represented by the Greater Tarapaca Indigenous Cabildo (CIMTAR), their governance body" over a period of 100 years.

The center of the project—which translates to 'life of the goddess of the Cotuhé and Putumayo rivers' in the Tikuna or Poguta language—is an Indigenous territory of 245,000 hectares (the size of Luxembourg) in the Colombian Amazon, stretching from the country's border with Peru almost to its border with Brazil. It is named after the two rivers that flow through the land: the Cotuhé that flows north from Amacayacu National Park to meet the mighty Putumayo or Içá, a tributary of the Amazon river, right before the town of Tarapacá. Around 2024 people live in the 12 Indigenous villages there, mostly of the Tikuna ethnic group, but also from the Okaina, Bora and Uitoto. The tropical rainforest there is in a good state of conservation, even though illegal gold mining dredges have been detected in the two rivers in recent years. The majority of the reservation’s villages have a fair to critical level of access to public services like electric power, sewage, waste treatment and drinking water, according to the Indigenous Human Well-Being Indicators (IBHI) matrix developed by the state-run Amazonian Scientific Research Institute in collaboration with the communities.

The Greater Tarapaca Indigenous Cabildo Association (CIMTAR), the Indigenous authority that has historically governed the reservation, appears in the ColCX registry as the project owner, while Mexican company Global Consulting and Assessment Services S.A. de C.V. is listed as its developer. Several Indigenous leaders from the reservation, however, state that they know little about the initiative, which should be bringing them income to cover their basic needs and support their work caring for the rainforest.

"Zero on all counts: zero information, zero participation, zero benefits. We have no documents, we don't know what was sold, and we do not know what it was invested in," Pepe Cham García, a Tikuna Indigenous leader and CIMTAR's current legal representative, said.

“People have no knowledge of whether or not progress was made, and that generates concern. We don't know if there was any disbursement, nothing concrete. No information came from those responsible,” said José Herlinton Pérez, a former Puerto Nuevo village leader.

The fact that two leaders of this community say that they have not been given information or participation in the project means that the project might be in breach of several of the social and environmental safeguards designed for REDD+ projects in Colombia. They include obligations to be transparent in its information, to obtain the community's free, prior and informed consent, to ensure the full and effective participation of its beneficiaries, and to be accountable to them for its economic results.

The Indigenous inhabitants of Cotuhé Putumayo do not know more because certifying standard ColCX has not published the project design document (PDD, in the sector's jargon) that supports any initiative. Neither has ColCX published the project’s auditing report, which would have preceded its approval and authorization to sell credits in the voluntary carbon market. Something similar happened in the Cumbal case in the Andes.

We have asked ColCX for access to the project's documents since December 2022, as part of an exercise mapping carbon credit projects and market actors. Unlike its competitors, the US-based Verra and the Colombian Cercarbono and BioCarbon Registry (formerly ProClima), ColCX is the only certification standard operating in Colombia that does not make such documents public for all its projects.

Response from the certifier—whose parent company Canal Clima is part of Valorem, the holding company belonging to the Santo Domingos, one of the richest and most powerful families in Colombia—has been negative each time.

In January 2023, ColCX technical manager Catalina Fandiño told CLIP by email that "the design document for each project is confidential and is the property of the community and/or developer," adding that she would request them from the developer. Two months later, she followed up saying that "we didn’t obtain approval to share the requested information." In April 2024, after a new request, CEO Mario Cuasquén said he was barred from sharing it due to "a confidentiality clause that obliges parties to refrain from disclosing more information." In September 2024, Cuasquén explained that the Cumbal case had triggered a process of self-criticism within the Santo Domingo group, resulting in major changes to their internal policy that now does allow publication of these documents. However, he warned that this new policy doesn’t apply to Global Consulting's initiatives because of the aforementioned confidentiality clause in the developer’s documents.

The Indigenous people of CIMTAR, who theoretically own the project, have had no better luck accessing this information.

Unanswered information requests

Soon after assuming the legal representation of CIMTAR, Pepe Cham decided to write to those responsible for the initiative. On October 25, 2022, he sent a letter to ColCX introducing himself and requesting information about the project given that, in his words, "it claims to be located in our territory.”

"Neither I as legal representative nor the other members of CIMTAR's Executive Committee have any knowledge of the content, conditions and agreements that support this project and we have had no contact with the company Global Consulting and Assessment Services S.A de C.V.", he told them, as seen in e-mails that Cham provided to us. Two weeks later, ColCX CEO Mario Cuasquén replied that from their perspective as a certifying standard, the project "has been duly executed, under the protection of contract No. 008-2019 celebrated between Global Consulting and Assessment Services S.A. de C.V. and the Asociación Cabildo Indígena Mayor de Tarapacá CIMTAR.”

The certifier also forwarded Cham a letter in which Global Consulting CEO Barbara Lara told ColCX that "all activities related to the design, implementation and execution of the project that Global Consulting has carried out to date have been authorized by (...) CIMTAR and covered under Contract No. 008 of 2019 signed between Global Consulting and the Resguardo Cotuhé Putumayo - CIMTAR". She said that Cham's predecessor as legal representative, Marcelino Sánchez Noé, signed that contract and then, on March 21, 2022, sent a letter authorizing the start of the project.

The Mexican businesswoman also said that they had learned of the change of legal representative in the reservation, but argued that she knew that Sánchez had filed an appeal against the Ministry of the Interior resolution that confirmed said change. The company, she said, would refrain from intervening until that situation was resolved. "Global has decided to remain impartial and to wait for the appeal (...) to be resolved by the office of the Deputy Minister, since until that happens, it will not be able to share information with Mr. Pepe Cham García related to the project," Lara wrote.

Two months later, one day before 2022 ended, Vice Minister Lilia Solano confirmed the original decision of the Ministry of the Interior and ratified Pepe Cham as CIMTAR's legal representative. Though the Indigenous leader was officially recognized by the Colombian State, he received no response from Global Consulting to his request.

Another year and a half later, in mid 2024, Pepe Cham initiated a new round of letter writing seeking information about the carbon credit project active on the community’s land.

In an information request sent to Global Consulting on August 9, Cham once again underscored that "the community and its current leaders do not have full knowledge of the project and its conditions, a situation that affects both parties considering the aforementioned safeguards." He noted that his predecessor Marcelino Sánchez also did not have such information.

"It is CIMTAR community’s right, in accordance with national and international norms, to possess information and full knowledge of this process," he added, requesting documents referring to "the objective, duration, area, implementation conditions, financing conditions and administrative conditions" of the initiative. He also requested documents proving a socialization had taken place with the reservation's inhabitants and "especially (...) information on the economic benefits left by the project and how they have been distributed in the CIMTAR community, specifying amounts, people benefited, projects benefited, as well as the method, time and place of the disbursement of resources.”

More than six months later Cham says he has not received a response from the Mexican company.

That same August 9th, Cham sent a similar information request to ColCX, stressing the same points. On September 3, Mario Cuasquén responded, although he did not do so in substance. He argued that the public information request could not proceed, and again told CIMTAR's legal representative that he was not authorized to provide the requested information "in view of the confidentiality clause of the contractual agreements in force" and explained that he wasn't familiar with part of the data requested, especially the financial details. He closed by saying that "the project (...) can be consulted publicly on the ColCX website", despite the fact that the website does not include basic documents such as the PDD or the auditing report.

Frustrated by this lack of response, Cham sought help from three public entities. The Ministry of the Environment, which oversees the carbon market, responded that it "hadn’t received any response from Global Consulting", while the Ministry of the Interior, which oversees ethnic minorities’ rights, and the Ombudsperson's Office did not respond.

We have been requesting an interview with Barbara Lara of Global Consulting since March 2025, but have not received a response.

The Cotuhé Putumayo Rivers reservation is home to some 2,000 indigenous people, mostly of the Tikuna group, distributed in twelve villages, including Buenos Aires seen here. Photo courtesy of Rodrigo Botero / Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development (FCDS).

A tale of two CIMTARs

On March 18, 2025, Marcelino Sanchez, the Indigenous leader who signed the contract underpinning the project, sent us an e-mail introducing himself as the legal representative of the Greater Tarapacá Indigenous Council-CIMTAR and attaching a letter whose content we refrain from disclosing at his express request, in which he demanded that we not report on this subject.

Three days later, Sanchez sent a new e-mail, copying Barbara Lara of Global Consulting, attaching said letter, and highlighting his 15-year trajectory as an indigenous leader. "Right now our priority is the formalization of our Indigenous Territorial Entity and subsequent liquidation of the Association," he wrote in the email's body. Up until the date of publication, Marcelino Sanchez has not responded to interview requests or specific questions about the carbon credit project.

The title Sánchez used in his communications underscores one of the case's complexities: there are currently two governance bodies that coexist in Cotuhé Putumayo. On the one hand, there is the Greater Tarapaca Indigenous Cabildo led by Pepe Cham since January 2022 (as recognized by the Interior Ministry in April 2022) and on the other, the Greater Tarapaca Indigenous Council led by Marcelino Sánchez since March 2022.

This is so because the reservation is in the process of fulfilling the old dream of becoming an Indigenous territorial entity (ETI) with political-administrative functions. This was a promise of Colombia's 1991 Constitution, which declared the country multiethnic, but has only been implemented in parts. In 2018, the administration of Juan Manuel Santos issued a decree laying down a pathway for Indigenous lands located in the non-municipalized areas of Amazonas, Guainía and Vaupés to be incorporated into the national ordinance with a category similar to that of municipalities. From that moment on, the Indigenous territories began to create and formalize their Indigenous councils, which are the form of local government assigned to them by the Constitution (similar to a mayor and city council in the U.S. context). While this transition takes place and one replaces the other as the internal governing body, which will eventually administer and execute public funds directly, the two coexist.

According to the cabildo leaders, the reservation agreed in 2019 that they would create the Indigenous council but that it would only assume the cabildo’s duties once the new territorial planning figure was already fully functioning. “Everyone knows that the association will remain until the final moment in which we become an Indigenous territorial entity,” says Rafael Ahuanary, another local Indigenous leader.

To make things even more confusing, both governing bodies in the reservation—the cabildo and the council—use the same acronym, CIMTAR.

ColCX declined to discuss the project, claiming to have received a "request for non-disclosure of information" on March 18. According to the certifying standard, this communication instructed them that "as the body of representation and authority in our community, the Greater Tarapaca Indigenous Council is the only body empowered to make decisions on the disclosure and management of information related to our indigenous reservation", which is why ColCX claims it decided that "it must refrain from providing written or verbal information about the project". Finally, the certifier invited us to consult the public information of the initiative on its platform, which continues to include neither the PDD nor the audit report for the project.

Even though ColCX accepted the Greater Tarapaca Indigenous Council’s request for non-disclosure of information, at no point does the certifier’s platform mention it. Instead it publicly lists the Greater Tarapaca Indigenous Cabildo (CIMTAR) as both project "owner" and the "governance body" of the Indigenous reservation. The project validation statement also states that it is the Indigenous Cabildo that "acts on behalf of the community of the Cotuhé and Putumayo Rivers reservation".

The platform of certifier ColCX shows that the project owner is the Greater Tarapacá Indigenous Cabildo and not, as several of the actors involved now say, the Greater Tarapacá Indigenous Council, which shares the same acronym. Source: ColCX Platform.

We asked ColCX with which of the two bodies - cabildo or council - it interacts with, on what grounds it was taking sides with one of them and why has it not responded to Pepe Cham's months-old requests for access to the project documents, but the certifier didn’t respond. It also didn't answer who sent the letter asking it not to discuss the REDD+ initiative.

Beyond who is right about which governing body is in charge, one fundamental question remains: Why don’t the inhabitants of the Cotuhé Putumayo reservation have access to detailed information about the carbon credit project on their land?

The links between developer and auditor

How could a REDD+ project unknown to the Indigenous group implementing it be approved and then allowed to sell credits in the voluntary carbon market?

How could the world's 29th largest company by revenue end up buying the environmental results of an indigenous community without those producing them receiving anything in return?

The answer to these questions seems to have, just as it did in Cumbal, two prongs: a tangle of potential conflicts of interest on the one hand and a lack of due diligence on the other.

In the carbon credit value chain, a project only reaches the stage of certification and credit issuance after an assessment carried out by an external auditor, a third party hired by the developer but with an obligation to remain independent and impartial from it. Although the Cotuhé Putumayo auditing report is still not publicly available and certifying standard ColCX refuses to publish it, there is already an underlying problem: the multiple links between the developer and the auditor call into question this distance.

The clearest and perhaps most problematic link is that Bárbara Lara Escoto, Global Consulting's CEO, was a founding partner and shareholder of Deutsche Certification Body, according to company documents filed in the chamber of commerce, something CLIP’s investigation on the Cumbal case showed. In other words, the Mexican firm hired its manager's former business partners to evaluate their project.

There are also links in the opposite direction. Oscar Gaspar Negrete, the CEO and sole shareholder of Deutsche Certification Body as of June 2022 and also the person who signed the validation and verification certificates for the Cotuhé Putumayo project, appears in two Global Consulting and Assessment Services S.A. de C.V. company documents available in Mexico's Public Registry of Commerce. In one document, dated 2016, he appeared as a commissioner of its supervisory body, a role that is usually chosen by shareholders. In another document, dated 2019, he appeared as "representative and/or delegate of the shareholders’ assembly".

Gaspar Negrete was not only a business partner of Barbara Lara in the Colombian auditing firm, but was also linked to the Mexican company that she manages today and that developed the project with CIMTAR. Both facts suggest that the companies might have a double conflict of interest, given that an auditor of carbon projects must "remain impartial with respect to the activity validated or verified, as well as free of bias and conflicts of interest," according to one of the international ISO standards that regulate their work and apply in Colombia.

Neither Deutsche Certification Body nor Global Consulting have responded to interview requests since March 2025.

By Gabriela Garzón and Miguel Méndez

In October 2023, two months after an appeals judge ruled against the Pachamama project, the auditor Deutsche Certification Body lost its accreditation. The Colombian National Accreditation Body (ONAC) decided to withdraw the accreditation the company had held since 2021 to assess greenhouse gas reduction projects, including REDD+ projects like Cotuhé Putumayo. A month later, ONAC's appeals committee confirmed and made that decision final. This means that the company can continue auditing projects in Colombia but, in ONAC's words, "it is no longer authorized to issue reports or certificates under the accredited status, nor use the accredited symbol, nor make reference to the accredited status".

The reasons for the auditor’s sanction are less clear. ONAC denied our request for access to the dossier supporting the decision, stating that "we can only share information that has been officially published," due to international standards and confidentiality clauses signed with its accredited companies. Its decision came five months after CLIP’s investigation detailing Deutsche Certification Body and Global Consulting’s possible conflicts of interest.

There are other points of concern for the Indigenous leaders of Cotuhé Putumayo. First, they don't understand how the project ended up being developed by Global Consulting given that, according to the six leaders’ account, there was an initial socialization meeting in the village of Puerto Huila around 2019 in which a possible project was discussed with a different company called Taita Samay S.A.S. One leader recalls that Taita Samay appeared as leading the proposal with Global Consulting as a support to prepare project documents and carry out social work. They say they still don’t know when or with which company the contract underpinning the project was signed.

In any case, all six leaders insist that a contract wasn’t signed during that first meeting, but that its purpose had been outlining a route towards an eventual project. “We reached an agreement to begin working, a plan on how to move forward. There was a commitment to meet again to advance on that planned path of work, but that never happened,” says Jhovanny Carvajal, leader of the village of Puerto Huila who attended that meeting.

“To this day we’ve all wondered what’s going on, because there is no clear and truthful information about the situation,” agrees Antonio Supelano, a leader of the Ventura village who was also present that day.

Global Consulting and Taita Samay share directors: Bárbara Lara Escoto, Global Consulting’s CEO has also been the legal representative of Taita Samay (whose name means 'father's rest' in Quechua) since 2019.

The six Indigenous leaders are also unaware of when Global Consulting's project entered the carbon market. Three years later, in November 2022, they even met in the village of Buenos Aires with a different carbon market company called Allcot to explore the possibility of doing a project together. They didn't get past that first meeting because at that point they became aware of the existence of the other initiative. "We detected it there, we asked for information, we didn't get it and we saw that it was risky to begin a project," Allcot's technical director Mercedes García Madero said. Even if CIMTAR's leaders ignored the other active project’s existence and hadn't even seen its documents, the risk of starting another project in the same place was that they would all end up selling the same environmental result twice, something known in the carbon market as double counting.

To make things even more complex, one of the villages that is part of the reservation, the Tikuna or Magutá who live along the Pupuña stream on the border with Peru, are considered an Indigenous people in a state of initial contact and therefore require additional protection given their vulnerability. The reservation is also adjacent to the area where the Yuri-Passe, two of the Indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation still existing in the Amazon rainforest, live. In November 2024, Colombia’s Interior Ministry established an intangible zone in the vicinity of the Pure River National Park and a buffer zone next to it to protect them. The existence of the Yuri-Passe was established by neighboring Indigenous communities and by the research of the late expert Roberto Franco in his famous 2012 book Bad Cariba.

The oil company client

As in the case of the initiative carried out behind the backs of the Indigenous communities in the Andean forests and paramos of Nariño, the best client of the project in Cotuhé and Putumayo has been the U.S. oil company Chevron.

Between September 2022 and May 2024, Chevron Petroleum Company—the main Colombian subsidiary of Chevron Global Energy Inc.—used 2.98 million credits from the project to reduce its carbon tax burden in Colombia, according to public records on the transaction platform of the certifier ColCX. A second subsidiary, called CI Chevron Export S.A.S., used another 21,427 credits. Other companies that also used Cotuhé Putumayo credits include gasoline distributor Zeuss S.A.S. (387,000), Alberto Ochoa y Cia S.A.S. (2730) and OZ EDS S.A.S. (500).

A significant part of those credits were used by Chevron after the problems involving the developer Global Consulting and the auditor Deutsche Certification Body the Nariño project became known. Since the Pachamama Cumbal initiative was suspended by a judge in July 2023, the oil company used 1.3 Cotuhé Putumayo million credits; credits generated by a project that the Indigenous people of CIMTAR say they know nothing about. Since ONAC withdrew Deutsche Certification Body's accreditation, Chevron has used one million Cotuhé Putumayo credits.

Chevron confirmed that it purchased credits from the Cotuhé Putumayo project from Global Consulting, with whom, in its words, “at the time we had a commercial agreement.” It added that “today Chevron Colombia has no contractual relationship with the developer of that project nor does it exchange credits of the mentioned projects or other projects”. (See Chevron's complete response here).

According to the oil giant, “Global Consulting at no time reported social or environmental problems in the Cotuhé and Putumayo reservation, nor in any other project [and] its reports highlighted that all legal and regulatory parameters were complied with.” The company added that the developer “recently let us know that the Indigenous authorities of the reservation have denied social conflicts caused by this project.” It did not answer which authorities stated this or who asked them. Nor did it say how much it paid for the Cotuhé Putumayo credits, or list the projects from which it has bought credits over the past five years.

Regarding the legal problems of Global Consulting’s project in Nariño, Chevron said that “it was aware of the legal situation surrounding the Pachamama Cumbal project, which is why, once the legal action filed by some members of the reservation became known, we asked our supplier to suspend the exchange and withdrawal of certificates from that project.” It did not answer why it used 1.5 million credits from another project developed, audited and certified by the same companies involved in the Cumbal project after the rulings against it. The oil company also failed to mention that, as another CLIP investigation revealed, it exchanged almost 289,000 Pachamama Cumbal credits after the court-ordered suspension (something it attributed at the time to the fact that its “supplier acquired without prior notice credits of said project for Chevron Colombia, which were not adverted in a timely way in our internal processes and mistakenly ended up being part of the offsetting for said period.”).

Chevron did not respond to questions about what due diligence procedures it conducts to assess the quality of the carbon credits it purchases or who makes decisions on such purchases within the company.

When asked if the Cumbal problems generated any self-criticism, the company said that “after analyzing the journalistic information surrounding the project in Nariño, we put in place a strategy to improve internal procedures and safeguards” and “we initiated a review to ensure the viability of the projects in which we invest, which includes the participation of international stakeholders of the corporation to assess future projects.” It did not detail these procedures.

The sum of peculiarities - a project unknown to its beneficiaries, documents that are not public, undeclared links between developer and auditor, a certifier that refuses information to the community and a buyer who doesn’t know the project reality on the ground - have sown serious doubts about the legitimacy of this environmental initiative.

For these reasons, on April 24, Pepe Cham filed a legal action on behalf of the cabildo requesting protection of their fundamental right to petition that, in his opinion, has been violated by Global Consulting. Cham wrote in the legal writ that “by having total control of the information related to the project development and denying effective access to it to the CIMTAR Association by refraining from responding to information requests,” the development company “evidences its dominant position as well as the defenselessness and subordination in which CIMTAR is left, being denied access to information and contractual documentation where the Association itself is supposed to be a party and regarding a REDD+ project that is allegedly being carried out in its territory.”

On May 8, Judge Henry Geovanny Ramírez sided with Cham, ordering Global Consulting and its Colombian subsidiary SPV Business S.A.S. to “issue a substantive, clear, concrete and consistent response to the plaintiff’s request” within two working days of the judicial notification. According to the judge, Global Consulting “is not justified (...) in refusing to respond” to CIMTAR’s information requests.

Four days later, Global Consulting denied the CIMTAR cabildo’s request for information, arguing that a response may be negative as long as it explains the reasons for it. In her reply this Monday, Barbara Lara stated that the requested information “qualifies as a trade secret” and that “it has a commercial value derived from its confidentiality.” Lara also argued that the contract was signed not with the cabildo but with the reservation, through the council represented by Marcelino Sánchez, and that therefore “there is no legal or contractual basis to accede to the request” by Pepe Cham.

Even so, Cotuhé Putumayo leaders are confident that the income generated by the the project’s carbon credits will reach their reservation, to fund needs such as health or education for its inhabitants. “We’re looking for a good way out, for the collective benefit,” says Jhovanny Carvajal. “If everything had been well planned and organized, we wouldn't have so many shortages,” says José Herlinton Pérez.

As Indigenous leader Pepe Cham told the Ministry of Environment in another letter, dated January 2025, "this is a REDD+ project that belongs to us and of which we are the owners, but for which we do not have any information or a single contractual document.”