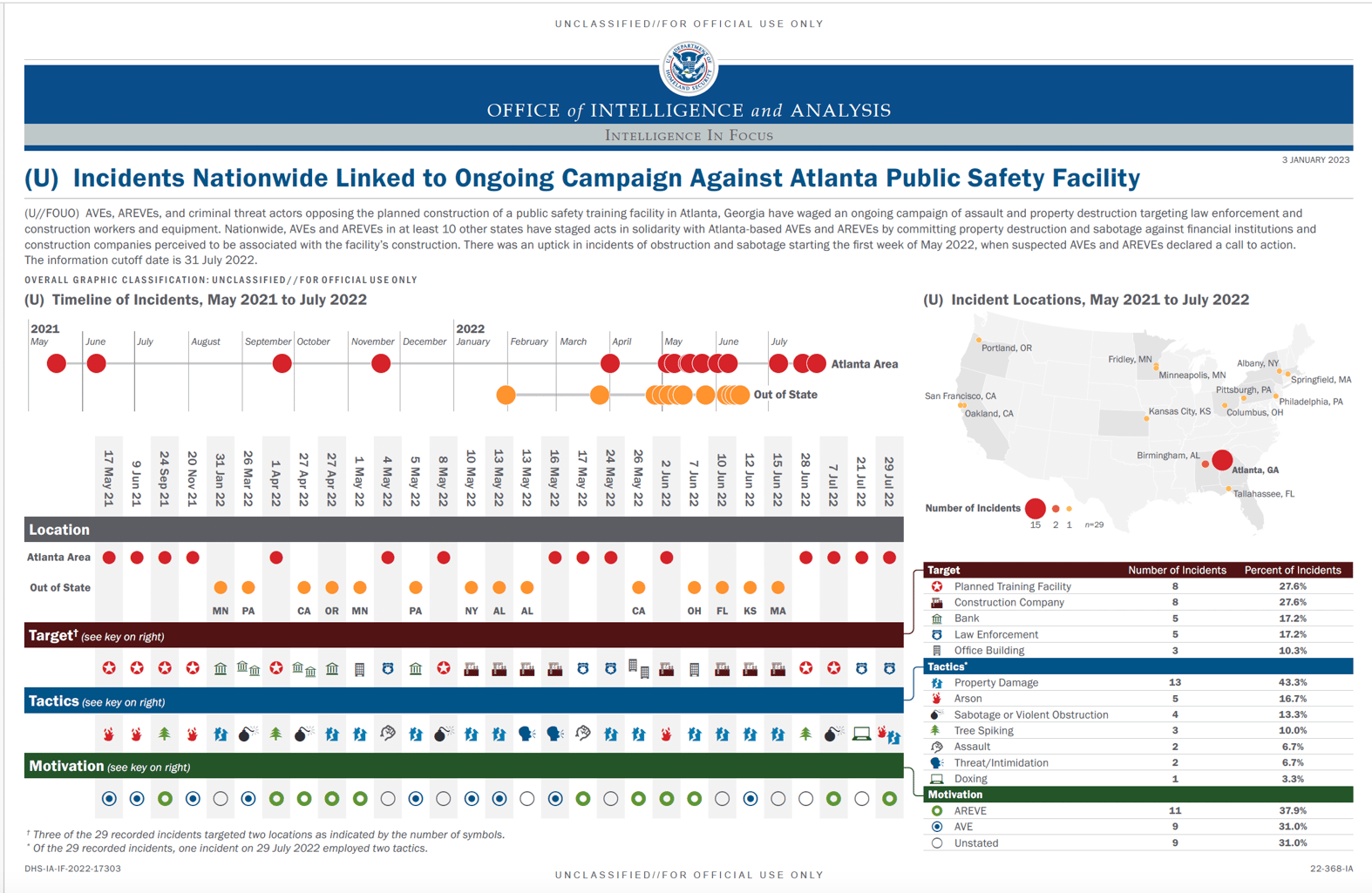

In early 2023, the Department of Homeland Security claimed in an intelligence report that anti-Cop City acts of vandalism around the United States, including window-breaking, were inspired by “anarchist violent extremism” and “animal rights / environmental violent extremism,” categories the agency uses to describe domestic terrorism. In a chart tracking the incidents, the agency used the symbol of a bomb to label acts of sabotage that appear to involve activists damaging ATM card readers with superglue. The agency also characterized anti-law enforcement sentiment and criticism of environmental harms as “DVE [domestic violent extremist] narratives.” The report, first posted by an anonymous Twitter, or X, user, was obtained by New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice in response to a public records request, and is described in a letter sent to members of Congress this week.

In the letter, sent Friday, civil liberties organizations, including not only the Brennan Center, but also the American Civil Liberties Union, the Center for Constitutional Rights, and the Legal Defense Fund took issue with the document and criticized DHS for “inappropriate use of federal counterterrorism authorities.” Recipients include the leaders of House and Senate committees focused on intelligence and homeland security.

“Reports like this and others that the DHS Office of Intelligence and Analysis have provided to state and local law enforcement appear to be motivating and justifying a politicized crackdown we’re seeing in Georgia,” said Spencer Reynolds, senior attorney for the Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security program and coauthor of a recent report that criticized DHS’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis for its overly broad mission and lack of protections for First Amendment Rights.

The civil liberties groups are demanding that the lawmakers press DHS to “cease disseminating information that treats ideological support for the Stop Cop City movement as an indicator of ‘domestic violent extremism,’” and that they “investigate DHS’s use of intelligence authorities and standards that have permitted repeated abuses, and adopt robust legislation to curtail them.”

For the past two years, community members in Atlanta have been organizing to stop construction of a $90 million police training center known as Cop City. In an attempt to physically block construction, a number of protesters camped in the forest where the training center was set to be built. Some also damaged property of businesses associated with the project.

In response, Georgia law enforcement charged more than 40 people with domestic terrorism, arrested operators of a bail fund, and indicted 61 people under the state Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, which was meant to target organized crime. One forest defender, Manuel Paez Terán, known as Tortuguita, was shot and killed by law enforcement, who said Terán fired first. No one but police witnessed the shooting. Terán was shot 57 times.

A mourner holds a painting of environmental activist Manuel Téran, who was killed by law enforcement during a raid to clear the construction site of a public safety training facility that activists have nicknamed "Cop City", during a press conference in Decatur, Georgia on February 6, 2023. (Photo by CHENEY ORR / AFP) (Photo by CHENEY ORR/AFP via Getty Images)

In arrest affidavits, Georgia law enforcement officials justified the domestic terror charges by claiming that DHS had classified the Defend the Atlanta Forest movement as “Domestic Violent Extremists.” DHS repeatedly denied that they had made such a classification. But the intelligence reports cited in civil liberties groups’ letter to lawmakers add to mounting evidence that DHS did repeatedly characterize Cop City opponents as domestic violent extremists, including in reports sent to law enforcement leading up to the charges, as Drilled reported recently.

The reports cited in the letter show that the agency was casting an even wider net, tracking incidents outside of Georgia that failed to meet even DHS’s broad definition of domestic terrorism.

A second DHS report dated two days after police killed Terán in January 2023, said that the activist’s death was prompting calls for violence against cops across the U.S., “potentially increasing the threat to law enforcement and construction and financial institutions associated with large-scale construction projects nationwide.”

Reynolds pointed out that DHS has an audience of tens of thousands of police. “Intelligence like this promotes exaggerated concern among law enforcement,” he said. “That exaggerated concern predictably results in unjustifiably aggressive arrests.”

The January 3 DHS report included a tally of 20 actions committed by “suspected DVEs who cited AVE and AREVE ideology,” acronyms for anarchist violent extremist and animal rights / environmental violent extremist. They also identified nine additional Cop City-related “criminal incidents” not attributed to domestic violent extremism. The activists primarily targeted law enforcement, construction companies, and banks, according to DHS, and committed assaults, arson, tree spiking, and doxxing.

The report didn’t list the specific incidents. However the Brennan Center searched news reports and activist comuniques for 13 incidents that allegedly occurred outside of Georgia, and identified eight cases that aligned with DHS’s descriptions. All were vandalism.

One of the incidents involved activists using super glue and plastic cards cut into thirds to jam ATM card readers at Wells Fargo and Bank of America locations in Philadelphia. Administrators of the blog Scenes from the Atlanta Forest posted a comunique about the incident, stating that the banks were funding the Atlanta Police Foundation, which supports the project. “This attack was done in solidarity and complicity with those disrupting the construction of a police training grounds in Atlanta.” It added, “We are excited to hear about construction workers being chased out and construction vehicles being messed up.”

The DHS report said the incident was inspired by anarchist violent extremism and marked it with the symbol of a bomb on a chart describing “tactics.”

The document was vague on what exactly DHS considers to be domestic violent extremist ideologies. It characterized “anti-law enforcement sentiment and criticism of perceived damages to the environment” as “DVE [domestic violent extremist] narratives,” and claimed that those ideas are being amplified because of anti-Cop City violence. The report also said that some of the so-called extremists “cited concerns about climate change as justification for incidents of property destruction.”

Asked for comment, DHS directed Drilled to definitions listed in a June 2023 strategic assessment on domestic terrorism. The document describes an array of motivators for “environmental“ and “anarchist violent extremism,” from Indigenous people’s rights to anti-gentrification sentiments to opposition to oil and natural gas infrastructure developments. The agency did not answer any other questions.

Fine print on the January 3 document states, “US Persons linking, citing, quoting, or voicing the same themes, narratives, or opinions raised by threat actors are presumed to be acting under their own volition, and to be engaging in First Amendment-protected activity, unless there are reasonable, articulable facts tending to show that they are acting at the direction or under the control of a foreign threat actor or violent domestic threat actor.”

Reynolds said that DHS’s characterizations “undermine social movements and political dissent of all stripes by conflating it with terrorism and suggesting that widely held political beliefs and views are themselves inherently dangerous.”

Notably, the report refers to people committing environmentally-motivated property destruction as animal rights / environmental violent extremists, or AREVEs, despite the fact that the movement to stop Cop City has little to do with animal rights. The document provides a hint as to why. A footnote references the movement Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty, or SHAC, which in the early 2000s sought to shut down laboratories practicing animal experimentation using direct action strategies, including property damage aimed at a range of associated businesses and individuals. In the report, DHS also labels SHAC activists AREVEs and claims they are a model for the Cop City opponents.

The SHAC case is valuable for understanding today’s anti-terror crackdowns on environmental activists. In the 1990s, animal product industries expended vast resources attempting to stop increasingly disruptive protest actions, which at times included property destructions or release of animals that the companies viewed as property. Radical environmental and animal rights movements, such as the Animal Liberation Front and the Earth Liberation Front, were more closely related in earlier decades than their modern iterations are now. Law enforcement strategies to quell so-called “eco-terrorism” and “animal enterprise terrorism” developed in tandem with these movements.

The industry’s efforts found fertile ground after 9/11. A group of Huntingdon opponents known as the SHAC 7 were a key test case for the federal government’s crackdown on radical environmental and animal rights activists. Members of the group ran a web site that posted activist communiques that at times included the home locations of people associated with the company and its contractors, or that claimed responsibility for anti-Huntingdon actions, from demonstrations to vandalism. Federal courts sentenced several of the activists to prison time, under an industry-inspired law especially designed for “animal enterprise terrorism.”

There is no federal domestic terrorism law specifically catered to environmental activists. However, state laws framed as protecting critical infrastructure have spread around the U.S. in recent years, amplifying penalties for activists trespassing on the sites of environmentally harmful projects.

The recently-released documents show that DHS’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis has established itself as a key federal node spreading concerns about eco-terrorism to local law enforcement officers and prosecutors who have their own suite of laws to apply. Indeed, the DHS strategic assessment shared by the DHS spokesperson noted, “Most EVE-related criminal activity in the last few years has violated state or local laws, rather than federal laws.”

In Georgia, it was a recently amplified state anti-terrorism law that was repurposed against environmental and racial justice activists. As the civil liberties organizations, put it, “DHS’s reporting has injected federal counterterrorism resources into the dispute.”