Photo credit: The floating storage unit "Armada LNG Mediterrana", a carrier for liquefied natural gas in the Marsaxlokk Bay, Malta. 2021. By Lusi Lindwurm, under a Creative Commons License.

In 2015, when U.S. fracking companies had a glut of gas on their hands and nowhere to sell it, lobbyists, front groups and trade associations came together and successfully convinced the Obama administration to do something that had been on the industry’s wish list for years: lift the country’s decades-old ban on oil and gas exports.

By February 2016, U.S. companies began exporting liquefied natural gas (LNG)—methane gas that has been cooled into liquid for transport—for the first time ever. Newly published documents from a three-year bicameral investigation into fossil fuel disinformation show that almost as soon as they began exporting LNG, the U.S. fossil fuel industry set to work pushing a new narrative that would help lock in gas exports for decades: the idea that LNG, despite being 95 percent methane, a potent greenhouse gas, is a climate solution.

The oil and gas industry is one that knows how to find and amplify the data that fits its narrative. In the case of LNG, those efforts have been aided, as they so often are, by an ecosystem of management consultancies, PR firms, and university researchers ready to provide credible-looking data and reports to support the idea that LNG is climate-friendly, attack science that says otherwise, and craft effective lobbying and advocacy campaigns.

Now, just as global governments faced an existential decision in the late 1990s—to continue burning fossil fuels and ignore climate science or begin a massive energy transition, a decision that the fossil fuel industry ultimately made for all of us—we face a new turning point on climate: will the industry get its wish and lock in methane gas for decades to come, or will governments protect their citizens this time around?

How to Green a Fossil Fuel

The idea that LNG is a climate solution hinges on two bold claims. First, the industry touts LNG as “low carbon”, a comparison that first, smartly, puts the emphasis on carbon emissions rather than LNG’s big problem—methane—and that compares LNG’s emissions to coal’s emissions. Oil and gas majors claim that LNG cuts carbon emissions by 40 to 50 percent. Industry spokespeople often refer to this as “settled science,” but the numbers are not so clear cut.

“It is grossly misleading to state that US LNG is good for the climate,” said Dr. Niklas Höhne, founder of the New Climate Institute and professor at Wageningen University in Cologne.

The study that industry generally points to on LNG’s climate impact is a 2019 Department of Energy analysis that found that the life-cycle emissions of U.S. LNG exported to Asia ranged from 54 percent to 2 percent less than local coal over a 20-year period. The range between 2 percent, a negligible amount, especially when you take into account that methane emissions are more than 28 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere, and 54 percent, the sort of meaningful emissions reduction the industry claims is guaranteed for LNG, is remarkably wide.

This range also depends on geography and energy use. In Europe, by contrast, the DOE found that LNG lifecycle emissions ranged from 56 percent less than coal to 1 percent more than coal. A peer-reviewed 2015 Carnegie Mellon University study found that LNG emitted 32 percent less than coal when used for power generation, but that emissions were 4 percent higher than coal when used as a substitute for industrial heat over the short-term.

Second, the industry’s marketing materials assume that LNG is always replacing coal, and thus always a climate-positive energy choice. That’s simply not true. According to data from Bloomberg New Energy Finance, most of Europe’s gas demand is driven by home heating usage, and less than 20 percent is coal-powered. That means that despite Europe being the top importer of U.S. LNG, in the vast majority of cases, US LNG is not replacing coal on the continent; rather, it is usually just replacing Russian LNG, or LNG from another exporter, according to Höhne.

Historically, the industry has also massively under-reported methane emissions, particularly those associated with pipeline or other transportation-related leaks. “Leaks” can also include regular industry processes, like venting—dumping gas directly into the air, something that tends to happen with increased regularity when the price of gas drops—and flaring, or the burning off of gas, which can happen either as part of routine maintenance or because a company needs to rid itself of excess inventory. Nor do oil and gas majors tend to include the emissions associated with liquefying gas for export, an enormously energy-intensive process, or shipping it across oceans. Forthcoming research from Robert Howarth, at Cornell University, claims that when the full lifecycle emissions of LNG are taken into account, it can be up to 24 times more emissions-intensive than coal.

The math on LNG didn’t always look so bad. When U.S. fracked gas was only being used domestically, it often was replacing coal for power generation, and it really did deliver reductions in the country’s CO2 emissions. U.S. CO2 emissions fell 2 percent from 1990 to 2021, according to the EPA, and the Energy Information Administration found that almost 532 million metric tons (65%) of that decline was attributable to the shift from coal-fired to natural gas-fired electricity generation. Even big environmental groups backed the idea of gas as a “bridge fuel” to renewables during the fracking boom (2008-2015), most notably the Sierra Club.

But the combination of news stories about how fracking fluid was poisoning water, more and more studies on methane emissions and their climate impact, and an explosive 2012 Time magazine story about how the Sierra Club had taken some $25 million in donations from fracking giant Chesapeake during the same years that its executive director was touting gas as a bridge fuel began to shift the relationship between climate activists and natural gas. The reckoning over U.S. gas, combined with a glut of the stuff, forced the industry to invest more into cementing the narrative that gas is clean, green, and a natural partner to renewables—and to begin looking for markets elsewhere.

From Bridge to Destination

In early 2017, less than a year after the first LNG tanker set sail from the U.S., companies began to worry about how to lock in this new revenue stream and maybe, finally, get gas out of its chronic boom-and-bust cycle. An advocacy strategy prepared for BP by global PR firm Brunswick Group, obtained by the House Oversight Committee in 2022, recommends that the company “position the positive role of gas in the context of advancing the transition to a low-carbon future.” Priority audiences for this message were listed as national governments (specifically the U.S., U.K., Brussels, Berlin, and China) and global stakeholders, including top-tier media, think tanks, NGOs, academics and industry leaders.

“Support for gas as a long-term solution can’t be taken for granted,” it notes, highlighting three key challenges to this support: “lower CO2 than coal, but still a fossil fuel”; “renewables dominate the debate in the future of energy”; and “emergence of methane as a flashpoint for gas,” a reference to mounting concern over methane emissions. The solution? BP should “continue to contrast gas as a low-carbon alternative to coal,” “positively present gas as a partner to renewables,” and “take [a] leading role on methane as Achilles heel of gas case.”

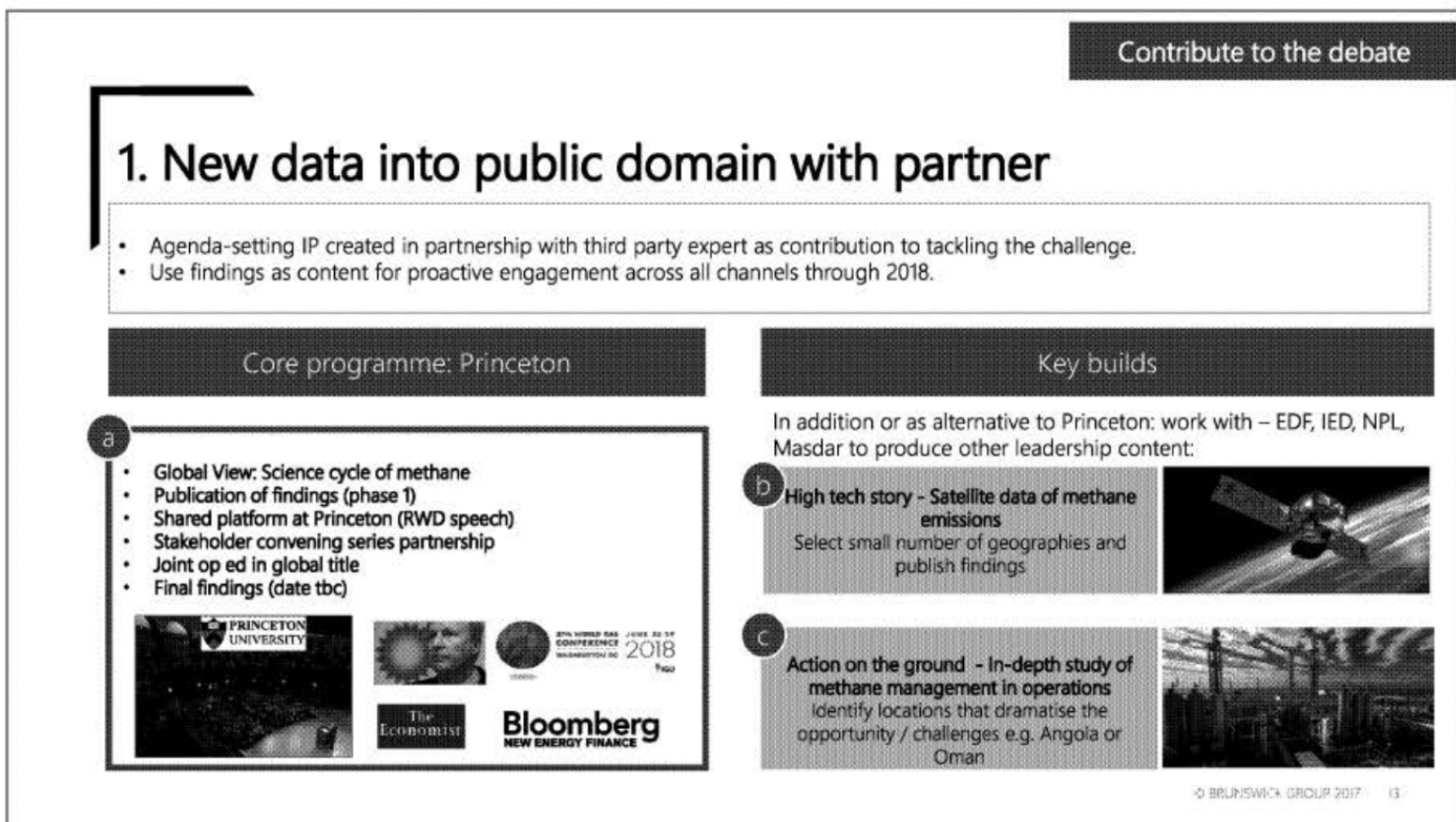

And not just by doing basic PR and advertising, either. Brunswick encouraged BP to “contribute to the debate,” starting with introducing “new data into the public domain with a partner.” The core partner in that effort? Princeton University, where BP funds the Carbon Mitigation Initiative. Brunswick also encouraged BP to work with Environmental Defense Fund, Masdar (the cleantech arm of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company), and other entities to focus the conversation around methane into a “high tech story” on satellite data, a mission the industry as a whole has very much accomplished in the years since Brunswick came up with its plan.

Brunswick’s 2017 strategy for BP

A March 2024 story about EDF’s satellite monitoring program that connects monitoring emissions via satellite with combating climate change.

Later that year, Joe Ellis, then BP vice president and head of U.S. government affairs, in response to an article about the potential of offshore wind wrote: “Promoting and protecting the role of gas as an increasing part [emphasis mine] of the energy mix is a paramount priority.”

In 2018, then-vice president and head of regulatory affairs Robert Stout gave a presentation on gas as a “destination fuel” not merely a transition fuel, and by 2019 the Brunswick strategy was in full swing as a BP workshop on “Gas and Power Advocacy in the Energy Transition” got underway in London. An agenda explained the context and purpose of the workshop this way: “At a time when the oil and gas industry is under increasing societal pressure, we are looking to articulate in a clear manner the important role gas can play in meeting the world energy needs in a sustainable way, not just as a transition fuel but as an enduring part of the energy system in decarbonized form [emphasis added].”

Gone were the “bridge fuel” days of 2015. BP, like the rest of the fossil fuel industry, was committed to gas as a “destination,” not a bridge.

That made the stories that began to pile up about the volume of methane emissions associated with gas a real PR problem for oil and gas companies. The month after BP’s London workshop, Randall E. Davis, one of its lobbyists, forwarded yet another one of these studies with the message, “This is an issue that will not go away, unfortunately.”

Ellis forwarded that email to an internal team of communications and public affairs’ execs at BP with the message: “This is not a helpful story. I’d like us to talk about beginning to push back, perhaps not as BP directly, on such reports and stories that miss the mark.” He asked the team to think about “how pushback or not pushing back supports our advocacy strategy for supporting gas” and ended with a question: “where are we on discussing the specific policy matters around the country that are anti-gas and which ones we might be able to influence?”

“Anti-gas policy matters” are, by another name, electrification policies, including bans on gas in new buildings. These documents show that as early as in 2019, BP was mobilizing to block state-level electrification policies.

The industry has known for decades that methane leaks, including intentional venting and flaring, were a potential problem for the story of gas as a climate solution. A 2015 study commissioned by The Natural Gas Council and prepared by management consultancy ICF lays the issue out clearly. On the draft obtained by the House Oversight Committee, an Exxon commenter notes: “Uncombusted methane is a big part of the inventory.” Uncombusted methane is leaked or vented methane.

As more and more studies on the impacts of methane piled up, the industry made more voluntary pledges. These were often coordinated through the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, a CEO-led collaborative of 12 oil majors that have committed to the Paris climate goals: Aramco, BP, Chevron, CNPC, Eni, Equinor, ExxonMobil, Occidental, Petrobras, Repsol, Shell and TotalEnergies. It also continued its marketing of gas as a clean, low-carbon fuel; according to Influence Map, the industry continues to this day to use this narrative to lobby against methane regulations in the U.S. and EU.

Never Let a War Go to Waste

Fossil fuel companies and their lobbyists got a brief reprieve from needing to sell LNG as climate-friendly when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. The resulting energy crisis created a new storyline for LNG: as a national security and international diplomacy imperative.

It took industry lobbyists just about a month to turn Putin’s invasion into a huge boon for U.S. LNG exports in the form of a U.S.-European Commission commitment to replace Russian gas with American LNG. In 2022 alone, the US fossil fuel industry locked in 45 long-term contracts and contract expansions, according to research by Friends of the Earth, Public Citizen and BailoutWatch, a major increase from the 14 such contracts signed in 2021.

But the victory was short-lived. European legislators resisted North American producers’ attempts to push them toward even longer term contracts, citing their governments’ climate commitments. Once again, producers found themselves needing to return to the story of LNG as clean and green.

In 2022, EQT, one of the largest LNG producers in North America and one of the few early fracking companies to survive the industry’s endless boom and bust cycles, released a report entitled “Unleashing U.S. LNG: The Largest Green Initiative on the Planet.” In it, the company suggests that the United States’ international climate plan should be to replace every country’s coal power with U.S. LNG, and posits that doing so would deliver “at least” a 48 percent reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. It sounds far-fetched, but is filled with data, charts, and footnotes that make it seem almost plausible; that’s thanks to McKinsey & Company, which provided data and analysis for the report.

In October 2022, EQT spearheaded the creation of the Partnership to Address Global Emissions (the PAGE Coalition), which lobbies both US and foreign governments to embrace American LNG as a climate solution. PAGE’s executive director is Christopher Treanor, a lobbyist with D.C.-based firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, and its members are some of North America’s top LNG producers: EQT, Enbridge, Williams, and TC Energy. The group’s website echoes EQT’s report, urging visitors to join it in the fight to “Replace Foreign Coal with U.S. LNG.”

PAGE met multiple times in 2023 with high-level European officials looking for support in its efforts to increase the volume of U.S. LNG imported to the EU. EQT is also a co-founder of Natural Allies for Clean Energy, which works particularly to position LNG as clean and affordable to marginalized communities, and both groups have been heavily lobbying the Biden Administration in the past year, claiming that its pause on approvals for new LNG export terminals will “substantially slow the pace of emissions reductions.”

“Gas has already proven to be a climate solution,” PAGE claims in a blog post. It warns that without consistent access to U.S. LNG, our allies in Europe “could once again become dependent on dirtier, less secure, and less reliable energy.”

That message has been echoed in op-eds by its supporters, including the think tank The Progressive Policy Institute (PPI). PPI has been a longtime supporter of the idea that LNG is the fastest way to reduce carbon emissions. Paul Bledsoe, former strategic advisor of PPI and author of most of its white papers and op-eds in support of LNG as a climate solution, has since left the organization, but sits on the PAGE Coalition advisory council and is a widely-quoted supportive source on LNG exports in the media.

But Höhne and other experts said that building out LNG infrastructure and extending contracts could lock the continent into gas dependency and slow its transition away from fossil fuels. EU countries currently use about 58.5% of existing LNG infrastructure to meet energy needs, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis’ (IEEFA) Europe LNG Tracker, and by 2030 the combined capacity of Europe’s LNG import terminals and related infrastructure could be three times higher than the EU’s expected LNG demand, creating an oversupply problem.

Ana Maria Jaller-Makarewicz, lead energy analyst on Europe for IEEFA, explained that EU policies have resulted in gas consumption declining from 2021 to 2023, while renewables increased.

“Energy efficiency has played a part in it as well as weather and demand destruction,” she said. “If this trend continues, the EU will need less LNG in 2030 than it does today.” Not exactly a cry for more U.S. LNG.

A New Climate Turning Point

After years of campaigning from climate activists, and the urging of some European politicians concerned about more fossil fuel projects coming to the continent, the Biden Administration moved in January 2024 to pause approvals for new LNG export terminals, saying it would take 12 months to evaluate how its approach to LNG meshed with its climate goals.

That pause won’t affect the seven already-operating LNG export terminals in the U.S.,though, or the five new projects that are already under construction, or the eight projects that have obtained their Department of Energy permits but are awaiting financing. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the projects under construction alone will nearly double US LNG export capacity by 2027. But extending the pause—provided Biden stays in office, which remains a big question mark—could at least stop it there.

Although industry groups like PAGE and the American Petroleum Institute have been up in arms about the pause, it may ultimately help their members’ bottom lines. Market forces have only continued to loudly tell LNG producers that there’s more than enough of their product out there already. Between the warm 2023-2024 winter and the rapid increase in LNG production, there’s a glut of gas on the global market again and that means prices are crashing again, which means gas is being flared and vented again, unleashing untold volumes of methane into the atmosphere, again.

In a video produced for this week’s bicameral hearing on fossil fuel disinformation, Jamie Raskin, Ranking Member of the House Oversight Committee, made the sort of “they knew, they lied” statement we’ve grown accustomed to hearing about oil and gas companies when it comes to climate change.

“Since the early 2000s, the oil industry has poured hundreds of millions of dollars into advertising natural gas as a clean and green energy solution,” Raskin said. “There's just one problem. Natural gas isn't clean, and it's not green. The main component of natural gas is methane, a greenhouse gas more potent and climate destructive than CO2, due to methane leaks. Some scientists believe natural gas is as harmful to the climate as coal, and big oil knows it.”

It feels like the 2015 Exxon Knew story all over again—except with gas the moment of truth is now. We’re in it. It’s not a story of what a company knew 50 years ago and buried. We’re not reading about a decisive choice between two paths that was taken decades ago. This is the story of what Big Oil knows today, and what governments are going to let them get away with.