Although Donald Trump has tried to distance himself from the plans laid out in Project 2025, several of the authors of the blueprint previously served in his administration and have already been floated as agency heads for a second presidency, so it’s hard to imagine the ideas they’ve presented are too far off what another Trump administration would bring. The plans are so extreme, though, that it might be difficult for Americans to imagine their government going that far. But some of the very same organizations that are part of Project 2025 in the U.S. have weighed in on similar plans in Latin America. For a preview of environmental policy during a second Trump term, Americans need look no further than Argentina.

On the eve of the Argentinian presidential election in 2023, conservative political commentator Tucker Carlson—who recently gave the first campaign rally speech of his career, at a Trump rally —met with then-candidate Javier Milei.

“Do you see climate change as part of a socialist agenda?” Carlson asked a spirited Milei. “Yes,” he replied without hesitation. “In fact, given the failure in the economic realm evident with the collapse of the Berlin Wall, post-Marxists moved class struggles to other aspects of life (…) For example, the agenda of man against nature, where man harms nature, when the truth is that the world has had other temperature spikes in the past. It is a cycle that exists regardless of man.”

Just as former president Trump has previously referred to climate change as a “hoax invented by the Chinese,” the current president of Argentina has been very vocal about his belief that climate change is a hoax. “Hello defenders of the idea of climate change,” read his tweet from October 2021, followed by a graph (from an unknown source) showcasing temperature fluctuations from the Paleolithic up to Medieval times, apparently reinforcing his argument that humans are not the cause of rising temperatures.

However, whether it’s man-made or not, climate change is happening and Milei and every other government leader is having to adjust accordingly. Milei’s approach, like Trump’s, has been to say the market will deal with it.

“Milei is not alone in his conceptualization of climate change as an economic externality or something that can be solved with market mechanisms,” said Daniel Ryan, former Director of Investigations at the Environmental and Natural Resources Foundation (FARN) in Argentina. “What makes him an environmental hazard is his lack of proactivity in creating said market mechanisms. If climate regulation is a cost, the most rational thing would be to find ways of making it less ‘costly’ to his idea of ‘freedom’.” But for Milei, that freedom is “wrongly tied to the idea that the expansion of extractivist activities will bring economic freedom to a country that has been sinking in an extractivist model and in an international context of advancing towards more climate resilience economic activities,” Ryan said.

From the outset of his presidential campaign, Javier Milei has forged close ties with right-wing leaders like Bolsonaro in Brazil, Orbán in Hungary, and Bukele in El Salvador, signaling his ambition to become Trump’s ally in Latin America. He has even earned the nickname "Trump of Patagonia" both on social media and in news outlets. Right now, no other alt-right leader outside the U.S. is rising in prominence like Milei.

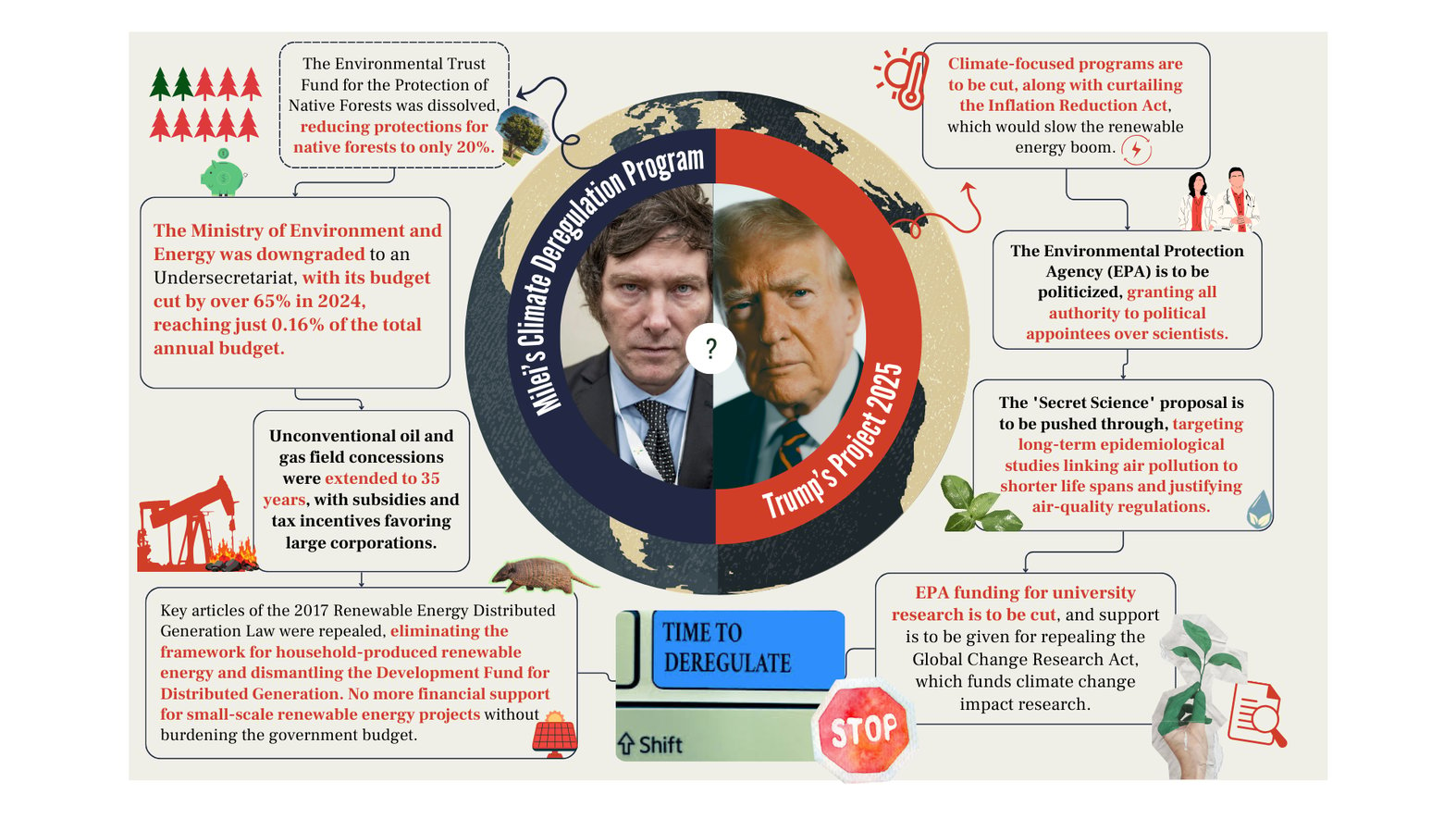

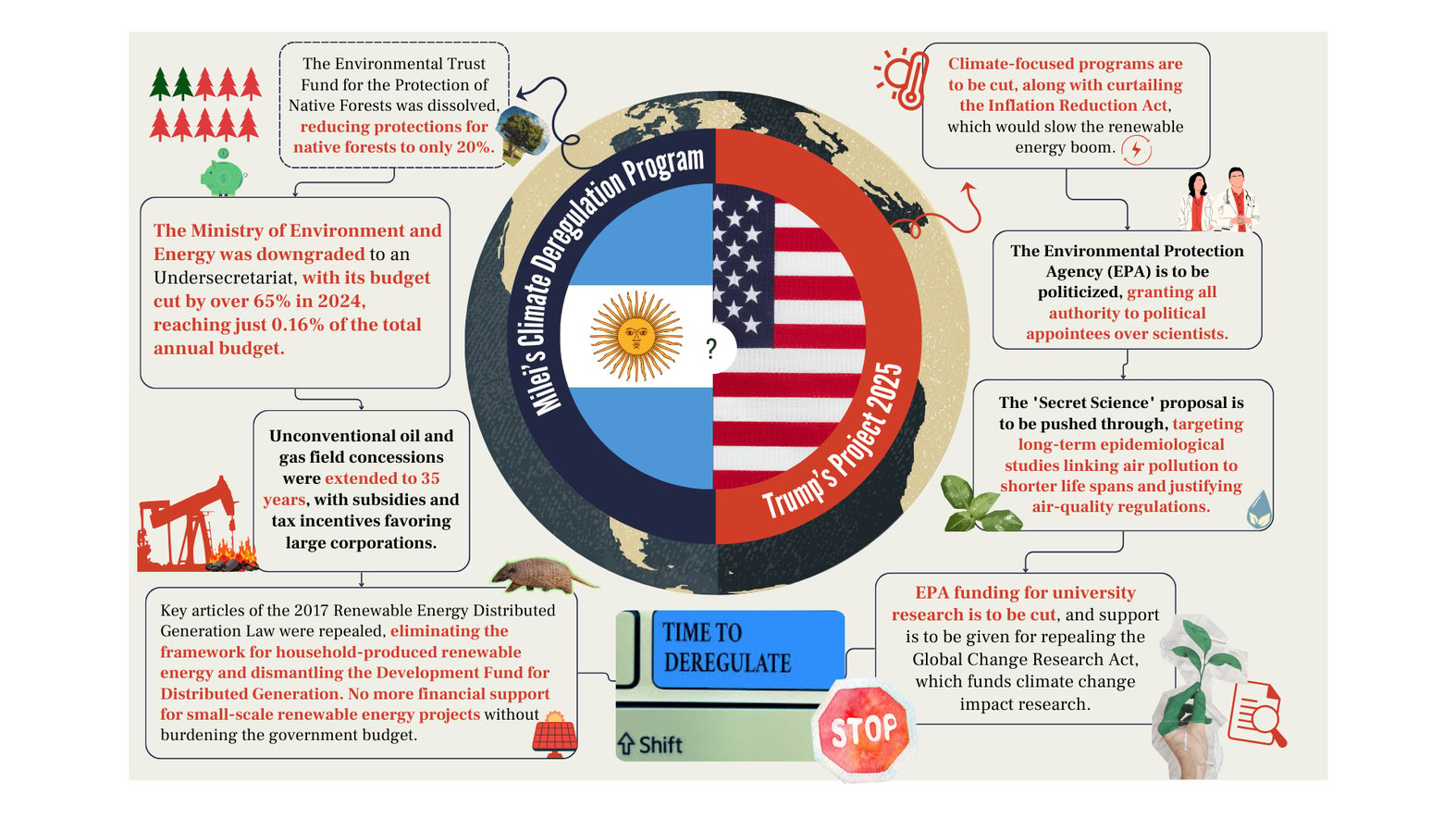

A comparison between Project 2025, written by several former Trump admin officials, and Milei’s deregulation program in Argentina.

Project 2025 proposes to eliminate climate programs, roll back federal commitments to climate action, pull the U.S. out of global climate treaties (again), and dismantle initiatives like the Inflation Reduction Act. Proponents argue that climate regulations hinder business freedom and wealth creation.

Milei’s strategy is closely aligned to the Project 2025 plan, and he wasted no time taking the first step: withdrawing from the United Nations' 2030 Agenda shortly after he was elected in December 2023. The immediate consequences are concerning and indicative of a broader trend within government agencies. In July of this year, the Association of Personnel of the National Institute of Agricultural Technology (INTA) reported that INTA has restricted staff from using terms associated with sustainability, such as climate change, biodiversity, agroecology and carbon footprint in official communications. In response to this, Ana Vidal de Lamas, the Undersecretary of Environment emphasized that the government and its agencies now prefer more neutral terms like impact and management. Vidal de Lamas contends that rising temperatures are “undeniable” yet “natural and cyclical” and that under the new administration, environmental policy will be deprioritized with a government not intending to be “super proactive” in addressing climate issues.

Adding to the politicization that the new administration brings to climate regulation, Javier Milei, in a memo sent to Foreign Minister Diana Mondino on December 18th, instructed all Argentine representatives abroad to align with his principles of “life, (financial) liberty and property”, making it clear that no projects, statements, or agreements that contradict these values will be supported by his administration. In this context, the need for responsibility and environmental action clashes with a vision that prioritizes short-term economic gain.

As Milei’s administration reshapes environmental language, it sets the stage for sweeping changes to Argentina’s environmental policy framework.

The first version of the Law of Bases and Starting Points for the Freedom of Argentinians, commonly known as the Law of Bases, was sent to Congress on December 27th, 2023, mere weeks after Milei took office, with more than 600 articles and a clear blueprint.

First, it aimed to roll back protections under the Forest Law (Law 26.331), reducing native forest protections to just 20%, leaving the rest vulnerable to logging. This could lead to rampant deforestation and biodiversity loss in a country that already faces brutal diminishment of its forest coverage, undermining local livelihoods and contradicting Argentina's international conservation commitments. The draft also proposed changes to the Glaciers Law (Law N° 26.63), allowing mining in sensitive glacial areas, threatening vital freshwater sources. In the fishing sector, the bill suggested extending fishing permits to 20 years without oversight from the Federal Fishing Council, leading to overfishing, damaging marine populations and jeopardizing local fishers' livelihoods. For the hydrocarbon sector, the draft proposed extending concessions for unconventional oil and gas fields to 35 years, maintaining subsidies favoring large corporations and proposed tax incentives allowing mining companies to operate with retention rates as low as 4.5%, compared to the 15% applicable to other economic activities. This disparity would have created an unlevel playing field that favored mining over other sectors, exacerbating the extractive model that has long characterized Argentina's economy.

In terms of energy transition, the draft law proposed the introduction of carbon markets, but lacked a comprehensive strategy for moving toward renewable energy. While it proposed a system for trading greenhouse gas emissions, it offered no concrete measures to reduce emissions or transition to clean energy sources.

In February and June 2024, environmental organizations and indigenous organizations protested at various points in the country, mainly concentrating near the National Congress in Buenos Aires. (photo credit: Ana Dominguez)

This first draft of the bill sparked strong reactions from civil society, including public opposition from more than 150 environmental and human rights organizations with a letter sent to the Congress in January of this year. “For Argentina to become a global powerhouse, it is crucial to build on what has already been achieved while avoiding the destruction of the progress made to date. The proposed changes to current regulations would lead to a reduction in the levels of environmental protection that have already been attained. Indeed, the principle of non-regression contained in the Escazú Agreement (Law 27.566) states that legislation cannot worsen the existing legal situation in terms of its scope and breadth,” expressed organizations such as FARN, FUNDERPS (Foundation for the Development of Sustainable Policies), the Argentine Association of Environmental Lawyers, the Collective for Action on Ecosocial Justice, along with Alianza x el Clima, Aves Argentinas, the Association for the Conservation and Study of Nature (ACEN), and the Circle of Environmental Policies.

Fortunately, that original draft was not approved by Congress; after more than half of the bill’s articles were rejected, senators decided the text was not suitable for further debate in the Chamber and sent it back to the committees of the Chamber of Deputies (Argentina’s version of the U.S. House of Representatives). However, a second draft of the bill was sent back to the Senate on April 25th of 2024, this time without a clear direction for environmental policies, but still with plenty of deregulation.

The most striking aspect of the new (and now approved) bill, is Chapter III, which brought some changes to the Administrative Procedure Law (Law 19.549), particularly around public hearings. The bill suggested that instead of mandatory public hearings, “authorities could use a public consultation or any other method deemed technically or legally appropriate to ensure the best possible participation from those involved.” This very vague sentence gives politicians a lot of leeway to choose whether a public hearing actually happens, or if it gets replaced with some alternative approach. In environmental matters, public hearings are the most effective way to guarantee public involvement in safeguarding the constitutional right to a healthy and sustainable environment—a right that’s written into Argentina's Constitution under Article 41. This also ties into Principle 10 of the 1992 Rio Declaration, which emphasizes that access to information goes hand-in-hand with public participation. Public hearings, vital for a thorough and open discussion about environmental issues, are no longer a certainty in Argentina.

The consequences of this new regulation are apparent in a recent Supreme Court ruling. On October 22nd, the Supreme Court of Argentina officially concluded a historic legal battle over environmental restoration in the Matanza-Riachuelo basin, one of the most polluted rivers in Latin America. In a unanimous decision, the justices ended their oversight of compliance with a ruling issued on July 8, 2008, rejected a collective environmental damage claim, and ordered hundreds of cases related to this significant environmental megacause closed. Before the decision was announced, on June 17 representatives of the Collegiate Body, formed by the Ombudsman of Argentina and five Civil Society Organizations, requested the Supreme Court to convene a public hearing to discuss the compliance with judicial mandates. The Court never convened.

Although Americans are not guaranteed the right to a healthy environment, the ability for communities to weigh in on big development projects has been baked into the permitting process since the early 1970s; Project 2025 (not to mention the Manchin-Barasso “permitting reform” bill) aims to limit public comment in much the same way Milei’s government has.

Another core objective of Project 2025 is to halt the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy. This includes repealing incentives for renewable energy projects and reinvesting in coal, oil, and gas to ensure energy "independence."

Similarly, one of Javier Milei’s first Decree of Necessity and Urgency (similar to an Executive Order in the U.S.), issued only three weeks after he took office, curtails renewables. He repealed articles 16 to 37 of the Renewable Energy Distributed Generation Promotion Regime (Law 27.424) passed in 2017 (curiously by the administration of former also liberal president Mauricio Macri, part of Milei’ support during his campaign). This law aimed to foster renewable energy integration into Argentina’s grid with a framework for distributed generation, where households could produce their own energy and feed their surplus into the national grid. By repealing the articles, Milei also dismantled the Fund for the Development of Distributed Generation, which promoted this small-scale renewable energy boost with financial support that posed no financial or fiscal strain on the government.

At the same time, Milei created new incentives for Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). Article 156 of the approved Law of Bases authorizes LNG volumes for a period of up to 30 years from the start-up of the liquefaction plant and enables permit holders “to export all volumes authorized under this status continuously and without interruptions, restrictions, reductions, or redirections for any reason during each day of the authorization period.”

Elsewhere in the law, article 161 describes the new version of the Regime for Incentives for Large Investments (RIGI), which seeks to bring "Strategic Long-Term Export Projects" to the country. Unlike the earlier draft, which explicitly listed sectors like agribusiness, infrastructure, forestry, mining, gas and oil, energy, and technology as potential beneficiaries, this version focuses purely on investment size, no matter the industry. Furthermore, none of the RIGI-specific sections of the law demand companies to submit Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) for their projects, nor does it require any evaluation of cumulative impacts.

There's also no mention of any obligation to create jobs at the local, provincial, or national level, nor are there any plans for boosting value chains or sharing technology. And in true Trump fashion, no sanction is foreseen for violating environmental regulations. Projects will be able to maintain the benefits of RIGI even if they contaminate rivers, soils and aquifers, destroy glaciers, or cause the extinction of a species. It is simply a set of unrestricted extractivist policies aimed at increasing oil and gas projects in the country.

While RIGI presents itself as the child of deregulatory governments, according to Maria Eugenia Testa, Director of the organization Environmental Policy Circle, Milei fails to understand that “climate deregulation as a way of cost-cutting is a false idea. Clearly what regulation does, even for governments that deny climate change, is to regulate future conflicts which are going to be more and more frequent between local communities and polluting industries. No regulation means more conflict, delayed projects, investments that have no return for companies and overall chaos.”

In the U.S, Project 2025 wants to shrink the size of federal environmental agencies and slash their budgets, most notably the EPA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The goal is to defund regulatory bodies that oversee environmental protection, particularly those having anything to do with climate policy, and to shift responsibility to the private sector. Milei’s administration has already undertaken similar measures by reducing the Ministry of Environment and Energy to an Undersecretariat under the Ministry of the Interior, and by cutting its budget by over 65 percent in 2024.

FARN’s analysis of the federal budget also shows that the budget for Environment (a program within the Undersecretariat) for 2024 was 82,228 Argentinian pesos, roughly equivalent to 80 dollars, for activities such as Environmental Policy in Natural Resources (roughly 13 dollars), Environmental Control (53 dollars), and Sustainable Development (around two dollars and 20 cents). A grand total of 70,234 Argentinian pesos, equivalent to 72 dollars, will go toward covering the expenses of projects such as the Conservation and Management of Protected Natural Areas (39 dollars), the Marine Protected Areas System (less than a dollar), and Training and Capacity Building (a dollar an 86 cents).

__

In the first six months of Milei's presidency, approximately 59,557 hectares of native forest were deforested in northern Argentina, as reported by Greenpeace through satellite imagery analysis—almost three times the entire size of Buenos Aires or San Jose, California. It’s an alarming rate for a country that has lost 8,000,000 hectares of its forest area in the last three decades due to deforestation and fires.

At the same time, according to a report from the Argentinian NGO Chequeado, Vaca Muerta—a geological formation and focal point for hydrocarbon extraction in the southern province of Rio Negro—is witnessing a sharp increase in waste production.

“Data indicates that waste generated from oil drilling and hydraulic fracturing grew by 35.2% from 2022 to 2023, resulting in 1,022,290 cubic meters of hazardous waste being treated, a stark increase from 756,230 cubic meters the previous year,” the report reads. This rise and the associated environmental risks could become even more pronounced with Milei's continued deregulation of the mining industry.

What none of us expect when a far-right president campaigns with an anti-environment platform is how quickly they’re able to cause large-scale and lasting harm. But in less than one year, Milei and his Latin version of Project 2025 have managed to roll back multiple environmental protections; obliterate the budget for environmental regulatory agencies; dissolve the Trust Fund for the Environmental Protection of Native Forests (Fobosques), leaving 80% of forest unprotected from deforestation and forest fires; encourage all provinces to exploit natural resources under the premises of Pacto de Mayo; and paved the way for mining and fossil fuel mega projects.

Milei and Trump embody the very essence of Tolstoy's insight: “Some people go through the forest seeing nothing but firewood.” Can we afford to let such shortsightedness define the future of our planet?