This story is co-published with the Center for Media and Democracy.

It’s been nine months since a jury in North Dakota delivered a devastating blow to Greenpeace, ruling that one of the best-known environmental networks in the world owed the pipeline giant Energy Transfer over $666 million. If even half of that sum were to prevail on appeal, it could be enough to shutter Greenpeace entirely in the U.S. However, the legal battle is still underway.

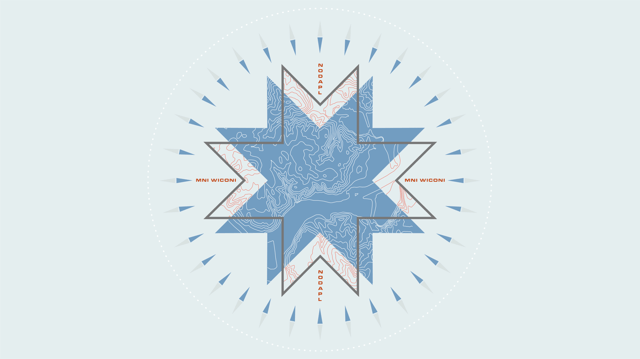

Nearly a decade ago, thousands of people poured onto an isolated prairie at the edge of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North Dakota to support the Indigenous nation in attempting to block construction of the Dakota Access oil pipeline. In the wake of the protests, after the pipeline was built, its parent company Energy Transfer filed a lawsuit arguing that the uprising had actually not been an Indigenous-led movement to defend the tribe’s water, sovereignty, and sacred sites, but was instead a conspiracy to thwart the fossil fuel industry, driven by the historically white-led nonprofit Greenpeace.

In March, a jury delivered an overwhelmingly favorable judgement to the company. Since then, the judge overseeing the case has reduced the damages by almost half. Greenpeace plans to demand a new trial. However, the judge has not yet issued a final ruling, which has put everything on ice.

Meanwhile, the court battle has hit U.S.-based Greenpeace Inc. hard. The nonprofit cut 20% of its staff this year via a voluntary separation program.

Despite that, Marco Simons, interim general counsel of Greenpeace Inc., said that the bruising legal fight has failed to paralyze the organization. “Like many other organizations, we will be approaching 2026 with a leaner staff,” he said. “But we plan to continue the work across our core campaigns (climate, oceans, and democracy) for the foreseeable future.”

Energy Transfer did not respond to a request for comment.

Thin Evidence and Jury Bias

Drilled, with support from CMD and Grist, spent a year investigating Energy Transfer’s case against Greenpeace, resulting in a six-part podcast called SLAPP’d and an in-depth article published by Grist.. The series explores the argument that the case against Greenpeace was a SLAPP suit (Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation) meant not to win on the facts but to make environmental groups afraid to support grassroots protests against the fossil fuel industry.

In addition to examining the merits of the case and the history of the law firms involved, the reporting team investigated the impact of the lawsuit on Indigenous defendants and uncovered details about a divisive legal settlement proposed by the pipeline company. Lawsuits like this often reveal information the plaintiffs didn’t intend, including, in this case, new details about Energy Transfer’s efforts to repress the Standing Rock movement and about potential safety issues during pipeline construction.

Drilled, Grist, and CMD were the only national outlets to send a reporter to cover the entire three-and-a-half-week trial. Energy Transfer claimed that Greenpeace was responsible for virtually all of the company’s protest-related expenses, from construction delays to property damage, loan financing costs to public relations bills. However, the evidence presented in court told a different story.

Greenpeace is actually an international network of independently run nonprofits, but the lawsuit specifically targeted two of its U.S.-based organizations, Greenpeace Inc. and Greenpeace Fund, along with Greenpeace International, which is based in Amsterdam.

It’s true that Greenpeace Inc. took part in the movement to stop the pipeline, but the organization’s role was limited.

On the ground at Standing Rock, Greenpeace Inc. helped support an organization called Indigenous Peoples Power Project, or IP3, which provided nonviolent direct action training to people who showed up to support the movement. The trainings discouraged violence and property damage. Greenpeace sent a total of six employees to work with IP3, some for a few days, others for a few weeks each. By comparison, the local sheriff estimated the peak population at the Standing Rock resistance camps to be in the ballpark of 10,000 people.

In addition to the half dozen employees who worked with IP3, Greenpeace Inc. held a Standing Rock supply drive, sent lockboxes designed to assist people in creating human chains that could help block construction, and donated $15,000 to IP3, according to evidence presented in court. Energy Transfer claimed that Greenpeace sent another $40,000 in donations to Standing Rock causes, although it is unclear how the company calculated that figure. The executive director of Greenpeace at the time also independently raised approximately $90,000 to support Standing Rock groups.

Although that’s a significant amount, it’s far less impressive than the $8 million in donations that came in through crowdfunding pages alone. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe reports raising more than $11 million — none of it from Greenpeace.

In short, the funding, supplies, and people Greenpeace sent to Standing Rock paled in comparison to the overall support that poured into the movement from other sources.

During the trial, none of the police officers or Energy Transfer workers called as witnesses remembered much about Greenpeace from their frontline experiences. Energy Transfer’s lawyers could only point to a single reference to Greenpeace in more than 1,700 pages of police operations briefings, and the organization was hardly mentioned in hundreds of pages of daily intelligence reports written by Energy Transfer’s security contractors.

In the deposition of Energy Transfer Board Chair Kelcy Warren, he asserted that an entirely different environmental organization, Earthjustice, was influencing the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

In addition to its on-the-ground claims, Energy Transfer also alleged that Greenpeace used defamatory statements in a propaganda campaign that convinced people to join the movement. However, the statements in question didn’t originate with Greenpeace. In fact, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe stands behind them to this day.

Tribal leaders were particularly incensed at the argument that Greenpeace defamed Energy Transfer by saying that the company deliberately desecrated sacred sites when it built the pipeline and that the pipeline passed through tribal land. Standing Rock has continued to assert versions of those arguments in its ongoing legal fight to stop the pipeline. To leaders of the Standing Rock nation, the lawsuit against Greenpeace is an indirect attack on the tribe and on Indigenous sovereignty more broadly.

Despite the many holes in the case, the jury upheld most of Energy Transfer’s claims. But a closer look at the jury selection process helps explain why. In the months leading up to the trial, mysterious newspapers appeared on doorsteps throughout the county. They featured articles reminding residents of the disruptions they faced during the pipeline protests. For example, one headline read, “THIS MONTH IN HISTORY, OCTOBER 2016: Area schools locked down as authorities respond to pipeline protests.” A murky trail of funding connected Warren, the Energy Transfer board chair, to these newspapers. One potential juror even brought a copy to jury selection.

As it turns out, seven of the 11 selected jurors and alternates had economic ties to the fossil fuel industry, and a large proportion of the jury pool expressed negative views of the Standing Rock movement.

Toward the end of the trial, one juror who worked in the petroleum industry even stepped forward to disclose that his work hours were at times charged through a company called MPLX, which transports, stores, and processes natural gas liquids and oil — and owns a minority interest in the Dakota Access Pipeline. The juror noticed the word “MPLX” on a document displayed as part of the case. He was allowed to continue serving on the jury anyway.

After the trial, Greenpeace argued in court that a number of the jury’s decisions and damage calculations conflicted with the law. In some instances, Judge Gion agreed. At issue were legal technicalities. For example, the jury awarded trespass damages to both Dakota Access LLC and its parent company Energy Transfer. However, the judge found that the plaintiffs only proved that Dakota Access owned land. In another example, the judge found that some of the defamation damages were duplicative.

Gion reduced the total damages awarded to Energy Transfer by nearly half — to $345 million. But that’s still enough to crush Greenpeace in the U.S.

The Anti-SLAPP Fight Goes International

Earlier this year, Greenpeace International turned to a Dutch court for relief. In 2024, the European Union adopted a directive meant to protect people from abusive SLAPP suits. Leaning on that directive, the group argued in a February complaint that the Dutch court should declare Energy Transfer’s suit a SLAPP and force the company to cover its expenses for fighting the lawsuit. Ultimately, such a ruling would block enforcement of any damages against Greenpeace International. The case is the first test of the anti-SLAPP directive.

Greenpeace International provides resources to regionally based independent Greenpeace nonprofits and helps coordinate their efforts. The evidence presented in court suggests that the organization’s most significant role at Standing Rock involved signing an open letter written by a different organization, BankTrack. More than 500 other people and groups also signed the same letter, which encouraged lenders to divest from the Dakota Access Pipeline.

When Energy Transfer asked Judge Gion in North Dakota to block Greenpeace International’s suit in the Netherlands, he denied the request. So Energy Transfer has now filed an appeal with the North Dakota Supreme Court. Industry groups including the American Energy Association, Grow America’s Infrastructure Now (GAIN), and the Institute for Energy Research have all filed amicus briefs in support of Energy Transfer.

As of 2023, GAIN was funded by Energy Transfer. In a deposition first published by Drilled, Energy Transfer’s vice president for corporate communications, Vicki Granado, said that the PR firm DCI is behind GAIN, and that Energy Transfer was paying $100,000 per month to keep the organization going. She also confirmed that Energy Transfer approved DCI setting up GAIN’s predecessor Midwest Alliance for Infrastructure Now, or MAIN.

A final decision from Judge Gion on the Energy Transfer lawsuit could come as early as at the next scheduled hearing on December 18. The same day, the state Supreme Court will hear arguments related to the Dutch case.

Regardless of the results, it’s yet another chapter in a free speech battle that could drag on for years and someday reach as high as the U.S. Supreme Court.