The Ndaoya community gathered to discuss solutions. Photo by: Dawn Attride.

On a dirt track off one of the main roads of Chongoleani, a coastal area in Tanga, Tanzania, live the Ndaoya, a community that was brought together by displacement. Amidst the half-built houses in their village, they gather underneath the sprawling umbrella of their resident Mjohoro tree to meet members of 350, a global climate advocacy organization, who are on a brief trip here. “Under this tree, the air feels different, purified,” Mohammed, the community’s leader, tells the group's visitors. The tree's fingers form a transient border between the balmy heat and the cooler, shrouded shelter; a liminal space that maps to the impermanence the Ndaoya now live in because of the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP).

The pipeline will snake along its course underground from Lake Albert in Uganda through the Tanga region of Tanzania, ending in Putini at the shoreline. Though construction hasn’t yet started here, its effects are tangible in the family lands now cleared and farming livelihoods now ceased. EACOP was sold to locals as a promise of a better life –– one where they could have jobs working on the project and better land after displacement.

A tense silence hangs in the air as the community regards the visitors: Baraka Machumu, an energetic local environmental activist, and members of 350. Mohammed clasps his hands in his lap and speaks candidly –– these people are here to listen and bring solutions, he says, nodding for others to speak.

EACOP’s announcement was hopeful for Chongoleani, says Pauline, a soft-spoken woman sitting to the edge of the group. “We were promised foreigners would buy from our business,” she says. A former coconut farmer in Putini, Pauline was moved twice since 2019, when she lost her land to EACOP, before joining this Ndaoya community. “Before, I used to plant, harvest, eat and have surplus to sell. Now, we sit idle and feel [like] visitors to this land… I have ten people who depend on me. If there were any benefits, we would have seen them by now. I’m not hopeful,” Pauline murmurs, eyes downcast.

“I don’t even have one tree left to my name,” Mwalimu, a former fruit farmer, says. His hands move in sharp angles, replicating his family’s farming plots that he lost in Putini. Each season, he says, he would bag hundreds of mangos and lemons from his 142 trees, earning $5,000 in profit. When he was forced to give up his land by the government, he was compensated with a one-time payment valued at a single season’s worth of produce—$5,000— and given 70 days to vacate.

Mwalimu began building a house in Ndaoya but the poor compensation didn’t leave him with enough money to finish it. The buzz of EACOP’s development also caused land prices to surge in the region, leaving many locals unable to buy new farmland for business.

Resource-rich, yet lacking return

“To stop Uganda from exploiting its natural resources in order to develop as a country on the grounds that we, as Europeans, have over-polluted or are over-polluting could be regarded as paternalistic, cynical, and selfish to say the least,” EACOP’s French developers, Total Energies, say. In Chongoleani, such development remains to be seen where communities have, so far, suffered net losses nearly 10 years after the project was first announced.

Human rights organizations estimate that 100,000 people will lose land as a result of the EACOP project, yet Total posit that only 5,000 will be affected and that they will be relocated into “better conditions.” The project will “leave no mark on the landscape” purely because the pipeline is underground and so is “invisible,” Total states. Yet the removal of crucially important mangrove trees and threats to marine life around the port in Tanga say otherwise.

Some impacts can’t be measured. The pipeline will disturb around 2,000 graves, despite urgent pleas from locals to the government. These pleas have fallen on deaf ears: development is the priority. Activists say those who disagree are silenced –– Lynn Kamande of 350, for example, tells me how an activist she knows who spoke out against EACOP was struck by a machete to the back of the head (he thankfully survived).

EACOP will be the world’s longest heated pipeline, transporting up to an estimated 246,000 barrels of oil daily at peak capacity for the next 25 years to the Tanga port, set for export to foreign markets. The Climate Accountability Institute projects that the pipeline's peak annual emissions will be double Uganda and Tanzania’s current fossil fuel emissions, if completed.

“If” is the large question looming over EACOP –– typical investors across Europe and the U.S. have declared they won’t finance the project. TotalEnergies, China National Offshore Oil Corporation, Uganda and Tanzania have committed more money to make up for the lack of funding. As of March 26, the first tranche of EACOP funding is complete but it remains to be seen if backers can secure the rest of the $5 billion needed to execute the pipeline.

Waiting in fear

While countries and corporations are still hashing out the if’s, when’s and how’s of extraction, communities like Ndaoya are dealing with the very real consequences of EACOP displacement. Others wait in fear of the same fate.

When the Bomba Sita community planned a recent meeting, for example, the location was changed at the last minute –– the community worried they were being monitored by local leaders who might report them to authorities. Instead, they held the meeting on their homeland, an orange farm. Here, the air is ripe and citrusy, a delightful oasis away from Chongoleani’s hectic main roads.

An elderly woman picking oranges at the Bomba Sita farm. Photo by Dawn Attride.

“Our parents were born here. We don’t know any other land,” Salim, a farmer in this community says. In 2017, the district councillor began to question their ownership of the farm and asked for proof. The community agreed to pay 300,000 shillings each (roughly $100) for adequate certification to the two acres of land. Then in 2023, the same councillor claimed their papers were fake and they had no rights to this land. The Ministry of Land called them thieves. And last year, people came in and uprooted some of their orange trees, Salim says, pointing to a cleared patch of land where a small shack is built, with a timber yard adjacent to it.

The community doesn’t know what’s happening on that patch of land, but it’s often guarded by a local man, and foreigners come and go to this site, surveying their land. “There is no progress of the construction of EACOP so far in our community but there is a map charting the way. We are waiting in fear,” Salim says, noting they feel EACOP land grabbing has opened the gateway for other investors to do the same.

Bomba Sita woman points to EACOP route on their land. Photo by Dawn Attride.

Land snatching is particularly prevalent in Tanzania compared to other African countries as, technically, the president owns all the land. Kenya was supposed to be the end destination of EACOP but, according to a source at Total Energies, the company pushed for Tanzania instead.

Bomba Sita has filed a case against the district commissioner and was due to have their first hearing in November, but their case still hasn’t been heard. The judge was absent that day, which doesn't surprise Machumu. “The government [often] uses that tactic to make the community members too tired to go to court,” he says.

Legal standstills as the project barrels on

“Eyewitnesses say company employees sometimes travelled in large convoys, at times accompanied by police, army and private security forces, which intimidated communities even more,” Global Witness reported based on their interviews with over 200 pipeline-affected people. One of them was Swalehe Nkungu, a Tanzanian farmer who was badgered into signing a contract he couldn’t read in 2023. The compensation was far below the cost of new land, and he and his family of 12 children spent the money trying to survive. He has tried to engage with civil society groups for help, landing him in multiple interrogations from government officials who threatened to cancel his passport.

Yet, TotalEnergies reporting is optimistic. In a recent project update, the company reported that 99% of households have been compensated. And that 97% of grievances are “solved and closed.”

If the project was as wonderful as developers make it seem, there would be support and not regular protests and arrests, says Dickens Kamugisha, chief executive officer of the Africa Institute for Energy Governance (AFIEGO). Kamugisha and six of his staff have been arrested, put in police cells and questioned, only to be released days later without being charged.

In 2020, AFIEGO and other NGOs filed a case in the East African Court of Justice against the governments of Uganda and Tanzania arguing that the project violates both international and regional environmental treaties and human rights charters. They also filed an injunction asking that EACOP’s construction stop until their case is heard. Like many legal actions against pipeline projects in East Africa, their case has faced serious setbacks and been dismissed many times.

“It’s in the best interest of the government and companies to throw out these hearings,” Kamugisha says. “[They] are taking advantage of that to proceed with the project as if there is no legal challenge.”

They continue to appeal their case.

While they have been battling out what Kamugisha calls “Africa’s climate case of the century,” EACOP construction has progressed, slowly but surely.

Environmental degradation beyond the surface

Mohammed, Ndaoya community leader, takes us to a local primary school. It’s lunch time. Some of the young students peek out from behind the gnarled trees in the schoolyard while others laugh, twirling around the newcomers.

Mohammed walks on. The terrain changes from the dusty, orange earth of the yard to a porous sand with plant shoots emerging, like fingers from the ground. Tiny crabs dart in and out of the holes, scuttling under the thumping rhythm of the footsteps. The flat landscape is broken sparingly with the silhouettes of mangrove trees. “The existence of mangroves will look like a fable to future generations,” Mohammed says, as he sits into the tree's limp cradle. In the distance a bell clangs, calling students back to class.

One of the main tenets of Kamugisha’s case –– and of many other critics' arguments –– is environmental destruction. EACOP’s route affects nearly 800 square miles of protected areas, disturbs wetlands and may affect water quality. Nearly a third of the project runs through the Lake Victoria basin, which 40 million people across East Africa rely on. In Tanga, locals are particularly worried about the marine ecosystem.

Mangroves sequester carbon at 10 times the rate of tropical trees, act as a natural flood barrier and are key players in Tanga’s marine biodiversity. To balance out the carbon impacts, Total plans to replant the trees elsewhere (it’s unclear where or when yet as Total did not respond for comment). This means little to the people of Tanga who have suffered severe coastal flooding and many of whom rely on the marine ecosystem for income.

Although pipeline construction is still stunted in Tanzania, the port building at Chongoleani has been moving along steadily, disrupting local fisherfolk activity. According to the EACOP Resettlement and Livelihood Restoration Plan, impacts to fisherfolk in Putini –– particularly those who don’t have boats –– are “severe,” meaning they can’t fish anymore when the jetty is operating, which is presumably the next 25 years. The plan lays out the losses and risks for both sea and land farmers, and suggests solutions like “borrow[ing] money from friends and relatives” or “borrow[ing] land from relatives.”

Tanga’s Coelacanth Marine Park is home to some of the best-preserved seagrasses and corals globally. Local conservationists worry that the activity and potential pollution from the operating oil port would destroy this ecosystem, and eradicate the home of some of the world’s oldest fish called coelacanths, referred to as “living fossils.” Oil spills are not an unlikely reality –– the EACOP Environmental and Social Impact Assessment confirmed that, “EACOP oil spills will occur over the lifetime of the project.”

Growing unrest among youth

Mohammed worries about the impact of EACOP on future generations. Following displacement, many parents can’t afford school fees or electricity for their kids to study at night. The ongoing torment of the project has left young people angry and emboldened to speak up.

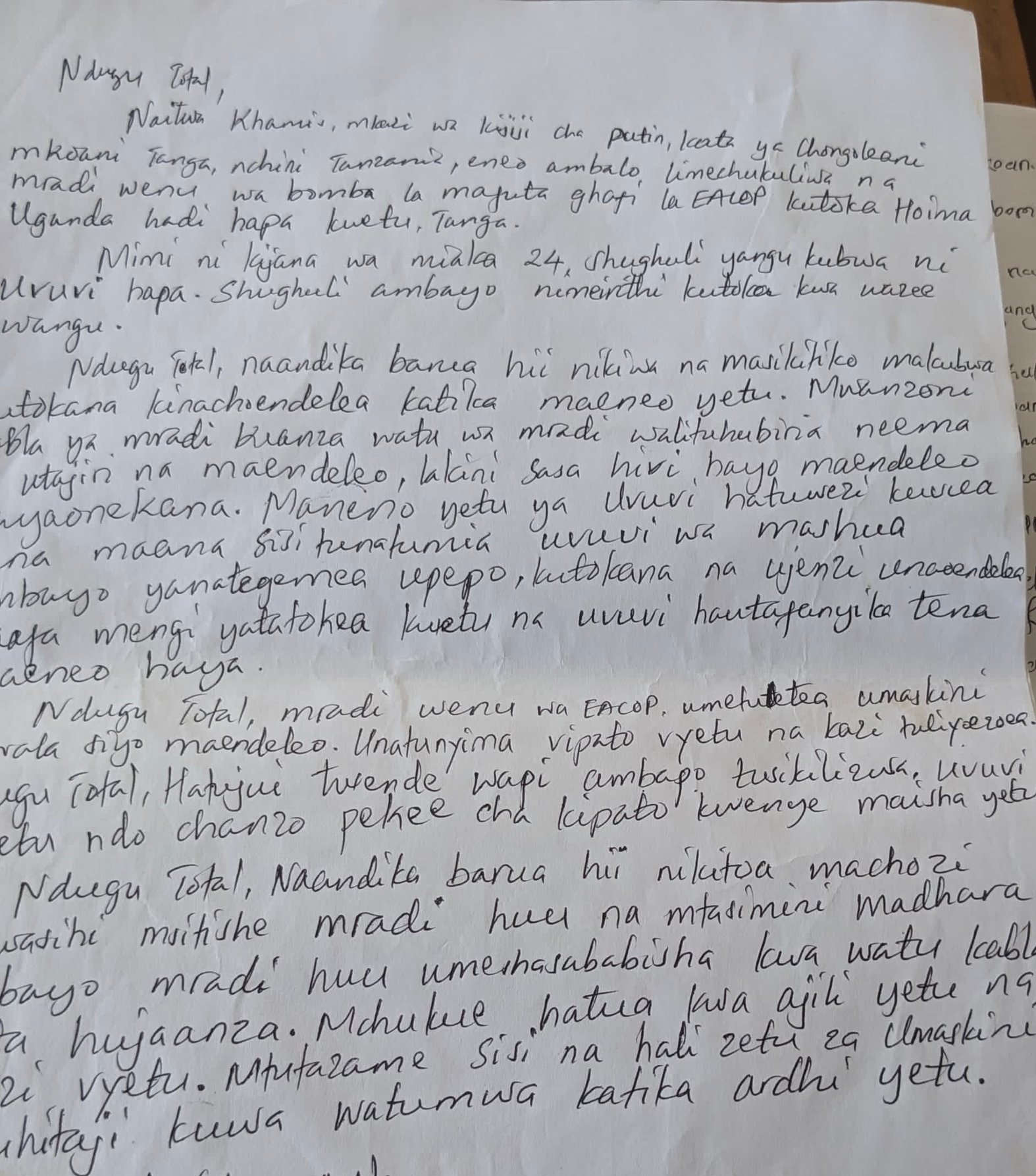

“Dear Total,” Machumu reads aloud from a letter. “Your project broke me. You took my light and education. Since you take my family’s lands [sic], they cannot support my study because the money you gave them is not enough to buy new farmland. How would you feel if that was your child? Is this what you call development?”

![Handwritten letters to Total Energies from Tanzania’s youth. [Credit: Baraka Machumu]](https://drilled.media/cdn-cgi/image/width=3840/cdn-cgi/imagedelivery/wTzk2S2Vnup17_3QtUMt7w/i23f3253f1c44ccb51b62be4b21e5a947/lg?q=https://prod-files-secure.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/a735deaf-8b61-4656-b83c-53e34949af51/ed1c490d-b1ff-43be-b617-ff6b3181905b/Tanzania_Letter1.jpg)

Handwritten letters to Total Energies from Tanzania’s youth. [Credit: Baraka Machumu]

Machumu has collected similarly emotional letters from Tanzania’s youth to send to Total Energies. At COP29, he shared their plight with the climate community.

Machumu, who works with Green Conservers, a Tanzanian youth-led organization that fights for climate justice, says he relies on international groups like 350 to deliver funding for local communities. At COP29, while Machumu was relaying stories of EACOP’s personal tolls, the Global North was short-changing developing countries with half-baked climate financing offers, causing leaders of those countries to storm out of discussions.

Local journalists who will report on the issues are disappearing, Machumu and Kamugisha say –– they are increasingly being silenced or bought out. The atmosphere of fear in Tanzania is far worse than Uganda, Kamugisha says, noting his struggle to get Tanzanian witnesses, out of fear of persecution.

So, what now?

2025 was the initial target for EACOP’s completion, but the pipeline is only half constructed, with growing pressure from international organizations and lawsuits.

Many locals have lost their land, which likely won’t be reversed whether EACOP is ever constructed or not –– the government has acquired the land. Elsewhere in Tanzania, such land snatching has forcefully displaced Indigenous Tribes to make way for the safari industry and Middle Eastern royalty. Left in limbo and grappling with food insecurity and poor compensation, concrete solutions for EACOP-displaced peoples look scarce.

350’s initial goal of the REPower Afrika campaign in Tanzania was to install renewable energy in pipeline-affected communities. On their visits, Ndaoya said they need solar fridges to help the women’s ice cream business and solar pumps for clean water. For Bomba Sita, they too need water pumps and lighting for their children to study at night. As of this month, it remains unclear whether 350 can actually deliver on this, saying they have “shifted their goals” towards campaigning and advocacy, without citing a causative reason for the change.

In Uganda, 350 has rolled out multiple solar projects to EACOP-affected communities. Their target for installation in Tanzania was the end of 2025.

As of this writing, the East African Court of Justice has not yet delivered a ruling on the civil society organization’s appeal. Given the lack of success of legal action against EACOP, it seems unlikely to stop the project. Yet, Kamugisha remains hopeful: “It is possible to stop the project and, in my view, even if we save one family, [if] we save one child who now suffers because of this project, it will be a success.”

This is the second in a series of stories looking at TotalEnergies’ expansion in Africa (you can read the first one here). It’s a continuation of our “New Oil Colonialism” project, which started in Guyana and compares the promises of oil majors to the reality on the ground in new oil countries.