We have covered before how the fossil fuel industry created the advertorial and how it continues work with media on the modern incarnation: sponsored content, created by the media outlets themselves. To be clear, it’s outlets’ internal brand studios that write op-eds, craft slide shows and videos, and produce podcasts for fossil fuel companies, not their editorial staff. But these services are explicitly marketed as a way to make corporate content mirror the editorial content in style and approach, and when it comes to fossil fuel advertisers it often directly contradicts what the editorial staff is reporting. In late 2023, we published a report detailing the many examples of this and delving into the peer-reviewed research that shows how misleading this practice is to readers.

This week, one of the researchers who has contributed the most to that body of evidence, Dr. Michelle Amazeen, at Boston University, published a new study looking at why this practice is particularly misleading on social media, and what media outlets might be able to do to make it less so.

Amazeen spoke with me about that research.

If you’d prefer to listen to this conversation, head over to today’s podcast episode!

Amy Westervelt: I'd love to know just a little bit of the background on what prompted you guys to undertake this study . What made you think, okay, we need to look at what might be done about this stuff?

Michelle Amazeen: Yeah, so I have been studying persuasion and misinformation for probably a decade now, and I started looking into native advertisements just broadly, not specific to the fossil fuel industry. I published a number of studies about the use of native advertising, how difficult it is for the public to be able to identify native advertising and, and distinguish it from news, reported news articles. And I think at one point I had a study where I contrasted two native advertisements. One was from, I think it was Cole Hahn, so it was a fashion designer. That ad was kind of, imitating, mimicking soft news. The alternative native advertisement was from Chevron, which was examining global energy consumption, and that was more hard news oriented.

And so this study looked at the differences between the two of those, how difficult it was for consumers to recognize that this was commercial content and not genuine news reporting. And that got me thinking, okay, well how dangerous is it for fashion retailers to be using native advertisement compared to companies such as chevron and other fossil fuel providers leveraging it. And so that's what got what got me thinking about who is using , this type of advertising strategy.

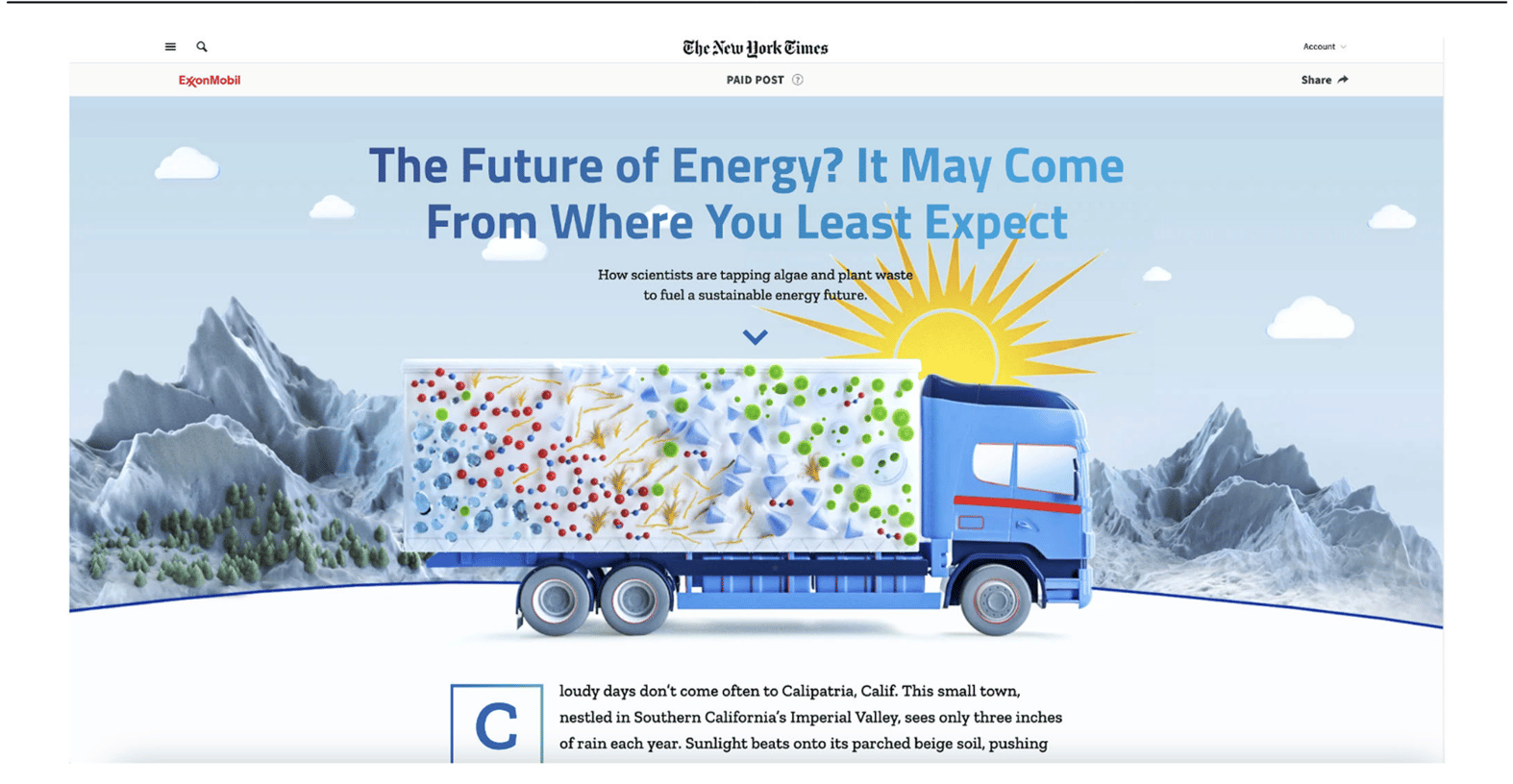

And I live in Massachusetts and I was aware that in 2018. Our state attorney general sued ExxonMobil for the claims that they were making in their advertisements, and I noticed that one of the exhibits in the lawsuit. Was a native advertisement that was created by T Brand Studio.

Amy Westervelt: Mm-hmm.

Michelle Amazeen: And so I think that was the impetus. So I've continued to do more studies on this. I've been working on a book. I have a, a book coming out from MIT press later this year, uh, about native advertising.

Amy Westervelt: Mm-hmm.

[Michelle Amazeen: And became apparent that it wasn't just happening in Massachusetts. You know, there's, there's many states and municipalities who have, brought forth these types of lawsuits. But there's not a whole lot of concrete evidence as to what exactly the impacts are, and so we decided, well, let's see if we can tease that out.

Amy Westervelt: It's interesting because, I've written about the native advertising stuff a bit and cited your research, so thank you. And actually the last time I wrote about it, I talked to someone doing this stuff, but probably not as much as other outlets.

And so the question was sort of like, why? Why continue to do it? And, the thing that really resonated with her the most, 'cause a lot of times newsrooms will just sort of say, oh, well, you know, we have a wall between ad and edit and, um, the advertisers aren't influencing our reporting and all that kind of stuff.

And I said, yeah, but that's not really the concern. The concern is that readers confuse these things for each other. And I pointed her to the studies that have been done on that. And that was the thing where she was like, oh really? I said, yeah. So it does seem like something that at least some newsrooms might be looking for ways to minimize.

But I wanted to ask you about the experiment that you ran. Was, was kind of mimicking a social media feed, right? Is that accurate to say?

Michelle Amazeen: Correct. Yeah.

Amy Westervelt: And maybe I could have you walk through the two possible interventions that people were, seeing in their feed and why you decided to look at those two things in particular.

Michelle Amazeen: Yeah, so I can preface it with the reason why we chose to. Format this as a social media post is because not only do these native ads live on the news organizations websites, but oftentimes these news organizations that are creating these ads. It's not an external ad agency. It's these in-house content studios that are creating it.

Often they are contractually obligated to amplify these native advertisements, meaning it's not just residing on their websites, but the news organizations have to amplify these ads on their social media sites and. What some of my previous research has shown is that when native advertisements are shared on social media, frequently the disclosures that are required by the Federal Trade Commission that distinguish them as commercial content, half the time those disclosures disappear.

And they are supposed to stick with, they're supposed to travel with the native advertisement no matter where it appears.

Amy Westervelt: Oh, interesting. So when it shows up on social that like paid for by thing is not there. Wow.

Michelle Amazeen: it disappears.

Amy Westervelt: Wow.

Michelle Amazeen: So that's why we decided to, okay, well let's show this in a social media feed format. I do have to, I do have to acknowledge that the New York Times. For the most part they follow the rules. Their labeling is good in, in terms of having labeling or disclosures, and they generally stay with the content when it appears on social media. So I wanna be sure that that's clear because in this study we are focusing on a New York Times created ad. Um, but they could make their disclosures more prominent, they could use more clear language. We adopted the language that the New York Time uses, which is paid post.

So that was one of the interventions is the. Disclosure, the New York Times uses the language paid post, which not everybody knows what that means. Um, and that that is one of the, uh, challenges of na, of the current regulation of native advertising is that the FTC does not require any sort of standardization in terms of what the disclosures say.

So the news outlet can call it whatever they want. They do. So it's, that makes it more confusing for the public when one outlet is calling it this, another outlet is calling it something else and so forth. So one of, one of the, um, interventions we had was the disclosure. And since this was an experiment, we had certain people who saw the disclosure and then other people, we did not show them the disclosure. So that was one of our manipulations. And then the other intervention we looked at was what we call an inoculation message. So it was a forewarning about the type of content that people may see in their social media feeds, and we had it. We had the source of that message as the UN Secretary General Antonio Gutierrez. And, he just basically talked about, what's happening, with the climate emergency and warning people to make sure the information that you see that you rely on on social media comes from credible sources who have relevant expertise and who aren't motivated to greenwash their activities or, or to cherry pick data.

So essentially encouraging people to be media literate. So that was the other intervention. Some people saw those messages, other people did not. That those were the people in our control group, the people in the control group. They saw a social media post about sushi, which sounds kind of random, but in the academic literature, uh, that that has been used many times before.

Amy Westervelt: That's so funny.

Michelle Amazeen: Yeah. Um, and then that was, so first there was either the inoculation message or forewarning or the control message, and then people then saw the native advertisement from. ExxonMobil. So either the one with the disclosure or the one without the disclosure, those were the treatment groups, the two treatment groups.

And then there was a third group that was, again, the control group who instead of seeing the native advertisement, they just saw a social media post about a restaurant review, which is. Anonymous and it was, they, we blurred out the name of the restaurant, just 'cause it, it didn't really matter.

Amy Westervelt: Do you have a sense of how well these things work on social versus on the outlets own website. I'm just thinking like, okay. I'm a climate reporter, have been for a long time. My own mother still occasionally sends me native ads as articles that she's seen on climate.

Michelle Amazeen: I mean, I, I believe that. So I opened my book with a vignette about me gradings my students. Papers and one of them, not one of them, a handful of them were citing a native advertisement. They

Amy Westervelt: No.

Michelle Amazeen: Yeah. And so I'm shocked and I'm trying to figure out how, how did they, how did this happen? And, well, I won't give away this story.

You'll have to get my book,

Amy Westervelt: Yeah. Oh wow. That's fascinating.

Michelle Amazeen: but Yes. So I mean, even, you know, it's, it's everybody, it's college students, it's. It's senior citizens, it's, it's even college professors who get fooled by this stuff.

Amy Westervelt: Yeah. Yeah. Um, okay. On the, it sounds to me like from the results of your study, the inoculation messages. Work much better than the dis like the disclosures are necessary and should, you know, and should and could be much more, large and prominent, but the inoculation messages seem to be much more effective.

Michelle Amazeen: So their functions are slightly different. The disclosure, the function of that is to allow people to recognize that the content is commercial in nature, whereas the inoculation. Is supposed to make people more resilient to influence.

Amy Westervelt: So I can see how that would work on social, I wonder how it would work on a website and whether you've looked at that at all. 'cause I know sometimes these ads will intentionally be run next to like legit reporting

Michelle Amazeen: Yes.

Amy Westervelt: I'm thinking especially around the potential of carbon capture. They'll often run this native ad that's like very positive about the potential of carbon capture right next to a reported piece. That's like pretty critical, and it has the effect sometimes I think of people thinking, oh, like there's two sides to the story or whatever.

Like, there's the jury's out, but,

Michelle Amazeen: right. Or sometimes they'll even sponsor a newsletter. Like there's a lot of environmental newsletters that are sponsored by a fossil fuel property

yeah, so don't think I've designed any studies to test that,

Amy Westervelt: Yeah.

Michelle Amazeen: but I, I agree with your conjecture that that probably muddies the waters for, for consumers.

Amy Westervelt: have You talked to any outlets in your research about how much might they be willing to do to counteract the potentially negative impacts of these ads? I don't know if you've heard anything from, from them on that front.

Michelle Amazeen: Yeah. Well, I mean, I guess it Who, who are you talking to? I mean, I've talked to reporters like climate reporters.

Amy Westervelt: Climate reporters, by and large, really want their outlets to do something about

Michelle Amazeen: Yeah. Well, there's many of them are quite a guest. It's at what's happening and some of them have actually left their. Employer because the employer is accepting fossil fuel money and creating ads around it.

Amy Westervelt: Mm-hmm.

Michelle Amazeen: I've also talked to reporters who talked to people from the content studio. The people from the content studio, the, the product market marketers or whatever you wanna refer to them as. They will, they will try and talk with reporters to, to coordinate, to find out what they're writing about. So despite that presumed firewall between the newsroom and the business side of things, it's very porous.

And you know, the, the reporters don't have much recourse, right? They can leave if they don't like it.

Amy Westervelt: yeah.

Michelle Amazeen: in terms of them saying to management, oh, we need to make these more clear. We need to make native advertisements more clear.

I don't know. I mean, Jill Abramson got forced out of the New York Times because in part she thought native advertising was a bad idea.

And another point is that years ago, I believe it was the New York Times, they swore off they, they committed that they would no longer take to tobacco industry ad dollars. Any kind.

Amy Westervelt: Yeah.

Michelle Amazeen: But in 2021, Philip Morris International came back to them, came back to a lot of the majors, the, the legacy media in the US and ran a native advertising campaign, not about cigarettes, but about their, what did they call it?

Tobacco harm reduction efforts. Vaping and some people pointed out, wait a minute, the New York Times and the Boston Globe are carrying this. They had committed that they would no longer take tobacco money and now they're violating it. So I don't know how strong those commitments are when they make them.

Amy Westervelt: I just have one more question for you around, I know that, the social media platforms themselves have been very resistant to, any kind of labeling or content moderation or things like that. Increasingly so in the last six months. I know I've seen people say that even just the unverifiable information kind of labels are censorship .

So I'm curious for your take on, on that. And I know that, even research, like yours is being targeted as sort of like censorship, so I'm, I'm curious what you think about that.

Michelle Amazeen: Yeah. So I actually, uh. Fielded a, a quick poll in January after Mark Zuckerberg made his statement about getting rid of the third party, fact checking, and, uh, found that, I think it was two thirds of Americans do want content moderation on social media, and the majority of them think that fact checking is beneficial, and they were.

Significantly less favorable towards, did he call it? Community notes,

Amy Westervelt: Right.

Michelle Amazeen: that's what he was gonna pivot to. So I mean, we have evidence. I mean, not that there was any question that, that Zuckerberg was doing this for any reason other than to bend to the new administration. Nonetheless, here's, here's empirical evidence suggesting that the public wants.

Amy Westervelt: Yeah,

Michelle Amazeen: You know, it's not censorship. You can still access the content.

Amy Westervelt: Right. You can still read it. You just have some context for it. Alright, thank you so much for taking the time.

Michelle Amazeen: Well, thank you so much, Amy.