In the spring of 2023, a dozen police vehicles arrived at an Indigenous camp in northwest British Columbia where people were protesting Coastal GasLink, a $14.5 billion gas pipeline that would run through the traditional territory of the Wet'suwet'en people. The police arrested five people, mostly Indigenous women, and released them without charges the following day.

It was the latest episode in a “troubling pattern of police intimidation” towards peaceful land defenders, according to the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, an organization that advocates for Indigenous rights. Those defenders are rejecting fossil fuel expansion because of the potentially heavy impacts on their drinking water, wild salmon and the global climate. They come from First Nations–a Canadian term referring to Indigenous people who aren’t Métis or Inuit–whose ancestors have lived in this area for thousands of years and never formally ceded or surrendered their territories to the federal government.

But there was no public comment on these latest arrests from TC Energy, the Calgary-based pipeline company behind Coastal GasLink—the firm which earlier tried to build the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline in the U.S. The same week that dozens of armed police raided the Wet'suwet'en camp, TC Energy featured an Indigenous elected councillor on the project’s Facebook page saying he was “very proud seeing our members being a part of building this pipeline on our Traditional Territory.”

The company meanwhile claims that it has “an unwavering commitment to reconciliation,” the process by which the federal Liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is attempting to repair centuries of violent and discriminatory policies towards Indigenous peoples.

“Reconciliation should never happen at the barrel of a gun,” countered Chief Na’Moks, a hereditary chief of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation, who for years has been a vocal opponent of the Coastal GasLink pipeline and fossil fuel expansion. “When they say this is in our best interests, or for our benefit, it is absolutely not. When you take away the freshwater and food sources from people, you’re taking away their freedom.”

Indigenous land defenders and climate activists say this is part of a years-long industry strategy to silence protest against massive new oil and gas infrastructure in Canada: loudly proclaiming support for Indigenous self-determination while deploying militarized force against protesters who don’t want polluting projects on their territories.

Kris Statnyk, a Gwich’in First Nation lawyer who’s been closely following the Coastal GasLink standoff, refers to this fossil fuel industry strategy as “redwashing.” “It’s a way of making their claims about their relationship with Indigenous peoples sound better than they actually are in reality,” he said.

“At this time, we are focused on safely completing construction to deliver lasting benefits for Indigenous and local communities, B.C., and Canada for decades to come,” a TC Energy spokesperson wrote in an email to Drilled.

The origins of this strategy can arguably be traced back to 2012, when four First Nations women helped launch Idle No More, a national protest movement calling for greater recognition of rights and sovereignty for Indigenous peoples and rejecting tar sands expansion on their traditional territories. For weeks, protests, blockades and hunger strikes dominated Canadian news and eventually led to a meeting between then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Indigenous leaders. Meanwhile, First Nations on British Columbia's Pacific coast mobilized to block a $6 billion tar sands pipeline known as Northern Gateway that was being proposed by the company Enbridge.

In short, resistance to the fossil fuel industry became part of the DNA of one of the most important Indigenous rights movements of recent decades. The oil and gas industry (and its political supporters) would not stand by quietly in the face of this escalating threat to its business model.

A national conservative group called the Macdonald Laurier Institute (MLI) responded by launching a yearslong research project dedicated to neutralizing First Nations opposition to resource projects. “The country faces the prospect of hundreds of billions of dollars of investment in the resource sector being held up by Aboriginal protests,” reads one paper from the think tank in 2013.

The Macdonald Laurier Institute has strong ties to the oil and gas industry. It has received $115,000 in contributions from the Charles G. Koch charitable foundation in addition to donations from the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers and the Exxon-owned Imperial Oil, one of Canada’s top tar sands companies. It’s also a member of a global coalition of nearly 600 neoliberal think tanks called The Atlas Network, with deep ties to fossil fuel billionaire Charles Koch and the oil and gas industry in general. Koch has funded several of the think tanks within the Atlas Network, which works to spread neoliberal policies that protect industry from regulation and the wealthy from taxes. Atlas provided a grant for MLI’s work attempting to win First Nations support for extractive industries.

“The Macdonald-Laurier Institute is an independent and non-partisan think tank,” a spokesperson wrote in response to detailed questions from Drilled. The Atlas Network didn’t reply to a media request.

The institute’s strategy for dealing with Indigenous opposition to oil and gas expansion appeared to have two distinct prongs. The first involved urging companies and governments to make First Nations “equity partners” in natural resources projects on their territories, allowing communities, some with high rates of poverty, to have partial ownership and enjoy a greater share of revenues. The second prong, as detailed in a 2013 MLI paper written by a former Lieutenant Colonel in the Canadian Armed Forces, called for security forces to employ counterinsurgency tactics against Indigenous protesters–especially young First Nations males from a so-called “Warrior Cohort” who have “a taste for violence and excitement”–in order to protect critical infrastructure.

The Macdonald-Laurier Institute claims this research was conducted on behalf of pro-industry First Nations leaders, reflecting a long-standing debate within Indigenous communities about the benefits and negatives of oil and gas expansion. Making these leaders the face of industrial projects had clear political advantages, providing “a shield against opponents that is hard

to undermine,” according to 2018 strategy documents from the Atlas Network and MLI.

Five years after this initiative had started, the Macdonald-Laurier Institute was claiming victory for transforming the national conversation. “Previously, the focus surrounding Indigenous groups highlighted their protests over pipelines and other major resource projects,” according to the documents. “Today, the conversation has shifted to show that Indigenous peoples are active across the natural resources sector.”

But whether all this actually benefited First Nations is debatable. As part of this strategy, MLI worked with its partners to delay and obstruct legislation designed to bolster energy rights on the traditional territories of Indigenous peoples–while claiming to be acting in those communities’ best interest. Nevertheless, the think tank had become an essential political bridge-builder. “Many elected officials now depend on the relationship that MLI has built with the Aboriginal community,” read the 2018 documents. “This connection provides credibility and support needed to battle opponents.”

One of the first major tests of this strategy took place in British Columbia, where for years oil and gas producers had been unlocking vast volumes of natural gas by fracking shale formations in the province’s northeast, polluting billions of litres of freshwater according to the environmental group Stand.Earth. The industry needed a way to transport this gas to the west coast so it could be liquified and exported to markets in Asia.

That was the genesis for two massive new projects. TC Energy would build Coastal GasLink, a 416-mile gas pipeline stretching to the west coast town of Kitimat. And a consortium of oil and gas companies including Shell, Petronas and PetroChina would develop LNG Canada, a $40 billion liquified natural gas export terminal.

This massive financial bet rested on the assumption of growing markets in Asia for Canadian gas (a gamble that industry experts now say is growing riskier due to the rapid global rise of renewables displacing fossil fuels.) But the pipeline also faced uncertainty at home.

It would have to traverse some of the most challenging mountainous terrain in the country, and it also needed to cross the territories of First Nations that were never officially surrendered in treaties to European settlers. “It's a place where jurisdiction over the land is still very much in dispute,” said Kai Nagata, Energy and Democracy Director for a B.C.-based environmental group known as Dogwood.

As TC Energy sent teams throughout the 2010s to convince First Nations communities along the route to support the pipeline, the B.C. government began making six-figure financial contributions to a new group called the First Nations LNG Alliance, composed of Indigenous leaders in favor of gas expansion. That group in turn formed a research partnership with the Macdonald Laurier Institute and the University of British Columbia, according to internal government documents made public through a freedom of information request. It soon became an outspoken advocate for Coastal GasLink.

The goal of the First Nations LNG Alliance was to “cooperatively advance shared interests with industry and government,” the documents read. Making Indigenous communities the public face of new gas projects could help win over foreign investors. “First Nations leaders should be in front of proponents to communicate this support because overseas proponents are paying attention to opposition groups,” explain the documents.

Still, by 2019, opposition to Coastal GasLink became impossible to ignore. Wet’suwet’en hereditary leaders and other members of the First Nation had for years occupied a series of camps along the pipeline’s proposed route. The industry advanced its efforts to co-opt the language of Indigenous empowerment while also working with law enforcement to assure aggressive responses to Indigenous-led resistance. TC Energy wanted to remove the camps, so it applied for an “injunction” from B.C.’s Supreme Court. “In effect, it’s a restraining order,” Statnyk said, “saying that [protesters] can't impede construction or they will be arrested.”

The TC Energy spokesperson told Drilled that the “injunction is in place to support a safe working environment for the many Indigenous and local women and men at our worksites.”

Once the injunction was granted, police had the legal authority to raid the camps. In January 2019, officers from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s Community Industry Response Group, a unit formed partly in response to anti-pipeline protests several years earlier in the U.S. at Standing Rock, broke down a checkpoint gate and arrested 14 people. “They looked like an army coming up with armored vehicles, attack dogs and snipers,” Chief Na’Moks said. The officers were authorized to shoot Indigenous land defenders if necessary, according to documents later shared with reporters.

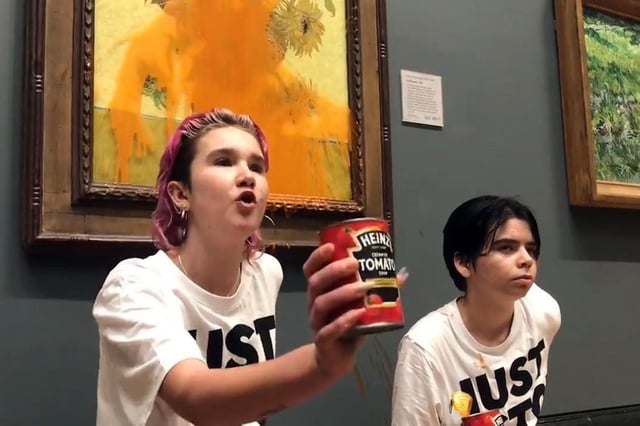

But people still refused to vacate the camps, and in February 2020, the RCMP made another round of arrests. Videos of rifle-carrying tactical squad members moving in with helicopters and vehicles were shared widely on social media, and within days the raids had inspired solidarity protests across the country. Protesters blockaded ports, roads and railways, bringing much of Canada’s rail and freight network to a halt.

Oil and gas proponents responded with their own counteroffensive. Stephen Buffalo, the head of a pro-industry group called the Indian Resource Council, did media interviews accusing the blockaders of being controlled by secretive U.S. funders, asking “who’s really pulling the string here?” Federal disclosures obtained by DeSmog revealed that his group that year received $100,000 from the oil and gas producer Canadian Natural.

In Alberta, home to the Canadian tar sands, then-Premier Jason Kenney accused the protesters of scaring away oil and gas investors by creating “the appearance of anarchy.” (Kenney has long cited Atlas Network groups as the source for his political worldview, and he’s been praised by the network for adopting policies proposed by a climate crisis-denying Canadian member called the Fraser Institute). His government in June 2020 passed a new law prohibiting protests that interfere with highways, railways, oil sands operations and other “essential infrastructure,” with fines as high as $25,000 and jail sentences of six months. Law professors and civil liberties experts in the province called it an “unjustifiable violation” of “fundamental rights and freedoms.”

Around that time, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers and a major oil and gas producer known as Cenovus helped launch a new group called the Indigenous Resource Network, which began making the case in national newspaper op-eds, resource conferences and presentations to the federal Canadian government that Indigenous prosperity is impossible without oil and gas projects such as Coastal GasLink.

All this has resulted in confusing parallel realities, where oil and gas companies and their First Nations allies loudly proclaim that gas expansion is healing the injustices of colonialism, while TC Energy relies on the RCMP, a police force created at the height of Canadian colonialism to assert dominance over Indigenous communities, to violently suppress pipeline opponents, many of whom are also First Nations.

These warring narratives have helped create “division and conflicts within communities, and all of that is very much in the interests of the oil and gas corporations and the government itself,” Nagata said. “It just helps to exhaust and wear down the resistance.”

Construction on Coastal GasLink is now more than 80 percent complete and the pipeline could start transporting gas later this year. The LNG Canada export terminal in Kitimat is expected to be operational by 2025. This is all being marketed to foreign investors as a triumph for Indigenous self-determination, even as more than a dozen people, most of them First Nations, face criminal charges for protesting the pipeline. During a third raid on Wet’suwet’en territories in November 2021, armed officers used a chainsaw to break down the door of a cabin holding land defenders and journalists.

Despite these raids, TC Energy sees itself as the victim of violence. Citing a 2022 nighttime attack on Coastal GasLink equipment that reportedly caused $20 million in damage, and which is still under investigation by the RCMP, the spokesperson wrote that “we have experienced unlawful and dangerous activities, including acts of violence by anarchists that have put people, property, and the environment at risk.”

Statnyk sees in the story of Coastal GasLink implications for climate protests and free speech all over the country—whether Indigenous or not. “There’s probably no one in Canada with a stronger position than the Wet’suwet’en,” he said, referencing the decades of court decisions and precedent appearing to affirm the First Nation’s sovereignty. “If this can happen to them on their territory…then it can happen essentially anywhere.”