This essay was published in partnership with The Nation.

“The world does not end at 2 degrees C,” Bill Gates told the British podcast The Rest is Politics in an episode that aired in January. Gates, one of the strongest and earliest supporters of tech as a tool to address the climate crisis, has spoken before about his belief that we’ll blow past 1.5 degrees—but his more recent assertions that 2 degrees C is unavoidable took many by surprise.

“There’s no stopping us passing 2C,” he said. “In temperate zone countries, in terms of your overall economy or livelihoods, it’s actually not a gigantic thing. Yes, you have to pay to make various changes, you have to have air conditioning… The really bad stuff is, say, you let it go above 3 degrees.”

I listened to the Gates interview sitting in a hotel ballroom in San Diego on January 23, surrounded by hundreds of attendees of the cleantech conference I’d come to observe. The conference was partially sponsored by an arm of Breakthrough Energy, the venture fund Gates founded in 2015 to invest in climate innovation.

I felt the familiar pit of despair in my gut that I get when I think about just how little time we have left to act on climate: of how quickly our world seems to already be spinning out of control, even at less than 1.5 degrees of warming, let alone the 2 degrees Gates seems to be hand-waving away. Outside the ballroom, San Diego was in shambles after nearly 3 inches of rain had fallen the day before, making for the city’s fourth-wettest day in history.

The ballroom—filled with people outfitted in techwear vests, slacks, and neat blazers—didn’t reflect my grim vibe. Across the table from me, picking at breakfast burritos, two investors chatted quietly about the difficulties of getting big businesses—including Caterpillar, one of the world’s largest manufacturers of oil and gas equipment—interested in small cleantech startups. “Don’t be surprised if you have a great dialogue and all of a sudden they stop answering you,” one said. Later on in the morning, the head of BP’s capital growth arm—clad in a blue puffy vest, looking every bit the part of the West Coast finance bro as the countless other white men in attendance—took the main stage for a talk titled “What's in Store for '24 – and Beyond? Perspectives From the Investor World.”

Nothing like a “Corporate Event Pump Up Playlist” to get people hype about colonizing the future. Photo credit: Molly Taft

The Cleantech North America conference is an annual event that brings together investors, entrepreneurs, tech gurus, talking heads—and, of course, representatives from major oil and gas companies, mining giants, petrostates, and other polluters. I’d come to observe panels and learn about new technologies, try to understand terms like purple hydrogen and 45Q, and figure out just how much weight to give Gates-ian claims that clean tech will save us. Bare minimum, I wanted to understand what cleantech even is.

For climate advocates, the tech world can seem like a pleasant but murky unknown: a well-dressed distant cousin who brings gifts at Christmas but sometimes doesn’t show up to family reunions. Climate optimists will point to the explosion of investment in the sector since the Paris Agreement was signed. Politicians tout cleantech as proof that tackling the climate crisis will make everyone rich. Oil and gas companies will eagerly show off how much money they pour into new technologies. Green capitalists will laud the progress the market is making to address climate in the future—without much detail as to how much that’s actually helping to cut emissions in the here and now. Critics of techno-optimism, meanwhile, say that focusing on technological feats at the expense of government action can delude us into thinking that we’re making more progress on climate than we are. I went to the Cleantech North America conference hoping to cut through the noise so that I could find the truth.

It’s an interesting time in the planet-saving tech world. After the pandemic, capital investments in clean tech skyrocketed in 2021 and 2022, only to fall significantly in 2023. The Biden administration’s policies, particularly the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, unleashed a wealth of new funding, making some climate tech investments much more attractive for investors who can count on government funds to help support their cash bets. A possible new Trump administration, however, threatens to undo a significant amount of that progress, and sow even more uncertainty. Once-hyped sectors, like fake meat, have experienced growing pains and a slowdown in investment recently, while other, untested technologies like hydrogen have exploded onto the scene as new darlings for investors.

Despite all of this, climate-related tech is still seen as a sure bet in an otherwise unsteady tech sector. In late January, while I was in San Diego, the New York Times ran a headline that proclaimed climate tech as “Recession Resilient.”

There’s no official definition or regulations for companies labeling themselves as “climate tech.” Wider still is the umbrella for “clean tech.” As I sat in the conference’s opening ceremony in San Diego, listening to the parade of companies honored on this year’s list of 100 top cleantech companies, I was struck by just how many different kinds of ventures can claim this label, from fake meat to technologies for “smart mining.”

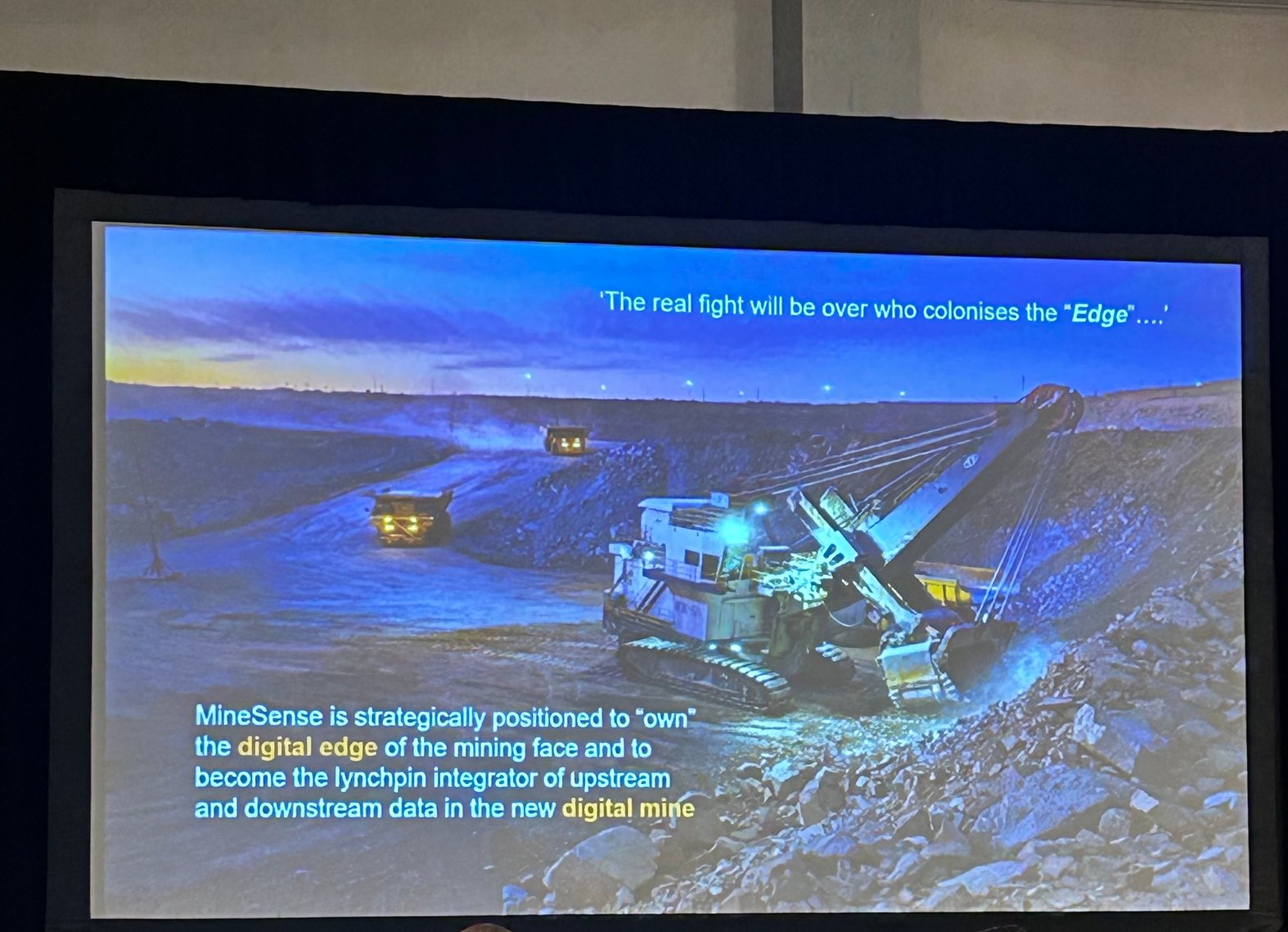

Part of a presentation from MineSense a “smart mining” startup Photo credit: Molly Taft.

Many of these companies seem, on the surface, to have a product that’s pretty good—or, at least, could be useful in the near future. I found myself most drawn in by the descriptions of things that sounded like they could be applied now: an electric vehicle charging app, a platform to oversee data from solar installations, extra-lightweight solar panels. I listened raptly during a pitch for a sealing technology for buildings to keep heat from escaping. Sure, it was dorky, but extremely practical. There were moments when it felt like I was just at a local trade conference for any other industry. But then some startup would wax poetic about its plans to revolutionize direct air capture or perfect hydrogen energy sources—technology that even optimists will tell you is years away from being deployed at scale—and I remembered where I was.

Despite the genial corporate blandness of the conference, cleantech is not a normal industry, but a sector that has been conjured up out of an urgent global call to action. This is a sector that has benefited from the Bill Gates and Al Gores of the world promoting its progress and potentials; a sector that has been highlighted and uplifted as a reason for climate hope as government action has lagged. And while other industries might have timelines dictated by investor interest or market trends, climate tech has a distinct set of scientific timelines operating in parallel to the venture capital investments and initial public offerings. Chief among these timelines is the mandate to move away from fossil fuel use as quickly as possible.

Yet, walking around the conference, you could hardly tell that we’re running out of time. Mentions of 1.5 degrees and 2 degrees were few and far between, as were discussions of any UN proceedings or the need to phase out fossil fuels—despite the science dictating that we need to cut emissions by more than 40 percent over the next six years in order to prevent the worst impacts of climate change. It was much more common to walk into a panel and hear a detailed breakdown of U.S. tax credits for carbon dioxide versus any focus on how last year was the hottest in recorded history. No one even thought to link the intense rains we’d all experienced in San Diego—which shut down much of the city —with increased warming. At least not out loud.

Some of this could simply be chalked up to a more widespread acceptance of climate as a problem, or tech as a solution. Climate startup owner Julia Collins told the New York Times that she used to include a slide laying out a blow-by-blow of the climate emergency in her pitch to investors; she has since taken out that slide. “We’re well beyond the point of having to prove climate change, or that it’s a big market,” Collins told the Times.

But it was hard not to associate the lack of urgency with some of the conference’s most prominent attendees: fossil fuel companies. I listened to a spokesperson from TC Energy—the owner of the Keystone XL pipeline, which will create more than 1 billion tons of greenhouse gasses over the course of its lifetime—speak on a panel about cleaning up urban energy distribution systems. I attended discussions hosted by the investment arm of Tokyo Gas, one of the biggest suppliers of natural gas in Japan, and Idemitsu, a Japanese petroleum company. At one panel sponsored by SLB—formerly Schlumberger, the world’s largest offshore drilling platform, which rebranded itself in 2022 to focus on clean tech—a startup owner proudly announced that Chevron, Equinor, and AGL had all invested in his company. (AGL, Australia’s biggest electric generator, was called “one of the most toxic companies on the planet” by one of its own investors for its overreliance on coal.) Reps from Shell, Chevron, SoCal Gas, Southern Company, and BP were all on the conference guest list. I kept accidentally making eye contact with one man wearing a Saudi Aramco-branded vest as he weaved through crowds like a contented shark.

Their attendance was a choice. Oil and gas companies are not totally necessary to keeping the cleantech industry going, one investor told me; there are plenty of funding sources that aren’t Big Oil. But existing energy companies do make good partners for a lot of startups, and are certainly ponying up some cash for certain ventures.

The investor encouraged me to notice which initiatives the fossil fuel funders were taking interest in: not in near-term technologies that could replace or knock out their product, like solar or EVs, but in longer-term ideas that will take a lot of research and capital, and give them room to keep producing as much oil as possible in the next decade. A startup that works in hydrogen or carbon capture makes sense for an oil company to invest in. Besides, fossil fuel companies have a lot of money to throw around, the investor told me, and it makes sense to diversify.

Isn’t there an innate conundrum, I asked, in a startup ostensibly committed to helping to solve climate change partnering with an oil company that has no plans to stop producing?

If there’s a bottom line to bring on funding to get the company off the ground, not really, the investor told me. “Money is green,” they said.

One of the many companies at the conference that had already taken fossil fuel funding is Amogy, a Brooklyn-based ammonia company that describes itself as “bringing the transportation industry one step closer to net-zero emissions.” Ammonia is one of those solutions that seems like it has real promise. As Maciek Lukawski, Amogy's VP of Strategy & Business Development, explained to me, ammonia is used around the world in fertilizers, meaning that the infrastructure already exists to create and ship it—unlike something like hydrogen, which would require huge amounts of money to build entirely new infrastructure. Amogy’s product—a tech that cracks ammonia to produce hydrogen for a carbon-free fuel, contained in a portable box—could be a game-changer for hard-to-abate industries like shipping.

Since launching in 2020, Amogy has already scored big with investors like Amazon, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,and Saudi Aramco Energy Ventures. Aramco, one of the most profitable companies in world history, has been frank about its objectives to keep producing oil and gas even as it invests in clean energy research and development. The Saudi Arabian government, funded almost entirely by its oil reserves, has been one of the biggest blocks to action since the UN climate process began in the 1990s.

As Lukawski told me, Aramco has already made its own significant technological strides in developing ammonia as a fuel source, creating the world’s first supply chain of ammonia with Japan in 2020. “They’re very well-positioned” to work on this specific issue, he said. “I think we’ll need someone who can bring the scale to low-carbon ammonia production.”

I pressed Lukawski—who, as one of several Amogy employees with a background in working for Big Oil, spent four years at Exxon—on whether he feels any sort of cognitive dissonance in his business partnering with Aramco.

“I have a six-month-old daughter,” he told me, eyes shining. “It makes you think in a certain way. Your focus shifts to thinking about the next generation. The energy transition needs to happen, and it’s not going to be easy, and it’s not going to be cheap—we need all hands on deck.”

–

As the three-day conference wore on, I became better at understanding how profit margins, not science, dictated how corporate types talk about climate. A spokeswoman from Chubb Insurance, a sponsor of the conference, was one of the only people I heard publicly mention searing heat across the world last year. According to the company’s financials, Chubb experienced $400 million in pre-tax catastrophe losses in the second quarter of 2023, compared to $291 million in the same quarter the year before. In the United States alone last year, there were 28 weather- and climate-related disasters that cost more than $1 billion each. Unlike Saudi Aramco or BP, whose profits rely on climate inaction, investors like Chubb have a real financial stake in seeing the tech pitched at this conference succeed.

Even among academics and other talking heads, who have no profit to gain or lose, the capitalist rhetoric didn’t always add up. Most conference attendees seemed, like Gates, to be in agreement that keeping warming under 1.5 degrees was impossible. David Victor, a professor at the School of Global Policy and Strategy at University of California, San Diego, told a crowd on Wednesday morning that he was “optimistic” about the state of the energy transition—especially compared to 15 years ago, when the world was on track for nearly 5 degrees of warming. The 1.5 degree goal “will not be met, and that will look like failure, but in terms of trajectory, that’s actually a tremendous success,” Victor said.

Victor, who argued that “deployment of capital” after the Paris Agreement has helped to not only improve technological outlook but also the political condition, stated that he considered initiatives to direct capital to accelerating net-zero targets to be “nonsense.” “What’s going to make [the energy transition] happen is when finance is just finance,” he said.

If the 1.5 degree goal is already a done deal—if, as Victor claims, the market left alone would be the best instrument to address climate change—it would make sense that startups that provide adaptation would be hot areas for entrepreneurs looking to make money in climate tech. Experts estimate that developing countries will need $2 trillion by 2030 to adapt to the changes they’re already experiencing.

But adaptation technologies consistently fail to get as much attention as other areas of investment. The Cleantech Group found that the adaptation sector made up just 7 percent of total cleantech investments last year, figures that track with research released last year from Oxford and the UN. “Engagement with technologies supporting climate adaptation and resilience has mostly remained flat as a percentage of investments, begging the question, ‘How prepared are we truly for the next phase of climate change?’” Cleantech Group CEO Richard Youngman wrote in the company’s annual report.

I asked a climate tech entrepreneur why, if everyone is in agreement that we’ll zoom past 1.5 degrees, investment in this specific sector is so under-pronounced. “That is the billion dollar question,” they told me. They said that a concept they called the ostrich paradox—a term coined by a University of Pennsylvania marketing professor and economist to describe psychological behaviors that create underpreparedness for disaster—was probably overwhelmingly to blame.

This concept, I think, is a little too forgiving of the capitalist framework that drives tech attitudes.

When we accept that the market will serve as the solution for climate, it seems only natural that more money would go toward solutions like ammonia, or hydrogen, or nuclear, versus setting up seawalls or monitoring wildfires. Treating climate tech as a hero inherently sets up climate as a long-term problem to be solved on schedules that match the stretched out “transition plans” of venture funds and oil companies —not on the schedule the planet demands. A capitalist system that shrugs off the 1.5 degree mark, when millions of people in countries around the world will inevitably suffer from that shift, is not one that is set up to help those same people adjust to an entirely new way of life.

At the end of the day on Tuesday, Breakthrough Energy sponsored a happy hour for conference attendees for “a chance to unwind, and [have] a little fun.” The southern California sun was shining once again over a bay flush with rainwater from the storms the day before. Those same smartly-attired people milled around tables set up on a grassy knoll outside the hotel, snacking on vegetarian hors d'oeuvres, while an iPad hidden behind a palm tree blasted a Spotify playlist titled “Corporate Event Pump Up Playlist.”

I thought about Gates’s casual dismissal of the 2 degree target, and his seemingly single-minded faith in the power of innovation to bail us out of the mess we’re in. “Big thanks to Bill for selling us fake tech and market solutions so governments wouldn’t actually take the actions that would’ve been required to avoid 2C of warming,” Paris Marx, a journalist and host of the Tech Won’t Save Us podcast, tweeted about the Gates interview. “He’s not the only guilty party, but he played an important role.”

The techno-optimists are half right: climate tech could help save the world. There were real ideas here that could truly tackle some of our thorniest problems. But depending on that pure innovation to somehow become a profit-making measure while it's helping to solve the climate crisis—to hold promising future technologies like ammonia and hydrogen beholden to investors, their fates tangled up in the balance sheets of companies who caused the very crisis they're purporting to solve—not only seems like a losing game, but a waste of time we simply don't have. There's no guarantee that even the most genius of the solutions I saw will become scaleable in a way that returns money; no guarantee that investors will suddenly become interested in adaptation technologies, while untold numbers of people suffer from storms or fires or floods or heat. Meanwhile, the BPs and Aramcos of the world are hooked on cleantech not because they're genuinely interested in solutions, but because they want a profitable side business that looks good on their balance sheet while they continue to pump more oil. Pretending anything else—pretending that the market can fix a problem it created—is make-believe.

But it's the only game that people with a pure, unadulterated faith in the power of capitalism want to play. I looked around at all the people my age drinking wine in the early evening light—probably many with kids at home, like Lukawski, who could also feel that nagging pull of panic every time they think about their child’s future. Despite climate tech’s new image as recession-proof, I’d wager that many of the people around me probably took a pay cut leaving high-profile, high-salary jobs—perhaps at oil companies—to try and make the world a better place.

I think they’re trying to do what they’ve determined is the right thing: selling innovation. In an age of near futility on climate, this is the only way they know how to do it.