Late on Friday, September 15, after hinting at it for A WHILE, California joined the growing list of climate liability suits with a whopper, accusing the world's five largest oil and gas companies (Exxon Mobil, Shell, BP, ConocoPhillips, and Chevron), as well as the American Petroleum Institute and 100 as-yet-unnamed entities that include operatives, think tanks and front groups that contributed to the spread of disinformation about climate change, of a litany of offenses, including public nuisance, misleading advertising, misleading environmental marketing, failure to warn, negligent product liability...the gang is all here.

Not at all to downplay the states, cities and counties that moved earlier on this—cases in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Hawaii, Baltimore, Colorado, Puerto Rico and more all walked so that California could run, and none of those cases would have been possble without the first round of cases a decade or so (Kivalina, New Orleans, and AEP), not to mention all the journalism and attribution science that has continued to build up the evidence base for these cases over the past decade. What's exciting about this case is that precisely because it is coming on the heels of those others, it's taken the strengths of all of them—the fraud claims of Massachusetts AND the liability claims of Rhode Island, Hawaii, et all AND the collaborative enterprise of the Puerto Rico climate RICO—and rolled them all into a super-case. And then of course, California is massive: its the nation's most populous state, the world's fifth largest economy, and it faces every climate impact there is.

It's also important to note that California's case is being filed after the Supreme Court cleared the jurisdictional hurdle that's kept these cases ping-ponging around the appellate circuit for the past five or so years when it opted not to hear oil companies' appeals on this front in the Boulder case, and all but told the fossil fuel defendants not to bring them that argument again. That ruling got all 30-odd cases moving towards discovery—the period in civil cases when documents are subpoenaed and current and former staff are deposed—an exercise oil companies have been trying to avoid at all costs.

As a native Californian, I've spent the past several months in a near-constant panic about my home state, and my family who are all still there. I left after spending two straight summers being smoked-in by wildfires (not two days, two entire summers) and evacuating three times. Never did I think flooding would be a primary concern, and yet this year I've worried about family back home facing not only floods but also a freak hurricane. So, on a personal note, it's encouraging to see the golden state fighting back. Especially because California's laws and lawsuits have the potential to shape federal policy, and yet it's been ceding that influence to Texas far too often lately.

And as a climate litigation nerd, it's fascinating to see all the strategies I've been following the past several years come together in this Avengers-style case. People often forget that California is also one of the country's largest oil and gas producers, so this case will be very interesting to watch from that perspective too; Chevron, one of the five named oil defendants in the case, is headquartered in California and its attorney, Ted Boutrous of Gibson Dunn, has been the primary spokesperson for the oil company defendants in climate cases that Chevron is involved with. A legendary First Amendment attorney, Boutrous often argues that anything his client has ever said about climate change—even if and when it was knowingly misleading—was in the interest of shaping policy and is thus protected under the First Amendment. He's also argued in several cases that the climate-related complaints filed against his client are SLAPP suits (strategic litigation against public participation) intended to punish them for their opinions on climate change.

The API has made similar claims, as has Exxon, both of which have alleged some sort of conspiracy against the industry because the lawyers bringing these cases sometimes talk to each other (a perfectly normal and not at all illegal practice). In a statement to The New York Times, Ryan Meyers, general counsel of the American Petroleum Institute, said: “This ongoing, coordinated campaign to wage meritless, politicized lawsuits against a foundational American industry and its workers is nothing more than a distraction from important national conversations and an enormous waste of California taxpayer resources. Climate policy is for Congress to debate and decide, not the court system.”

Sure it's a pretty standard industry statement, but let's unpack what Meyers is arguing here because it's illustrative of the industry's approach to accountability more broadly, and the various legal arguments it plans to deploy in these cases:

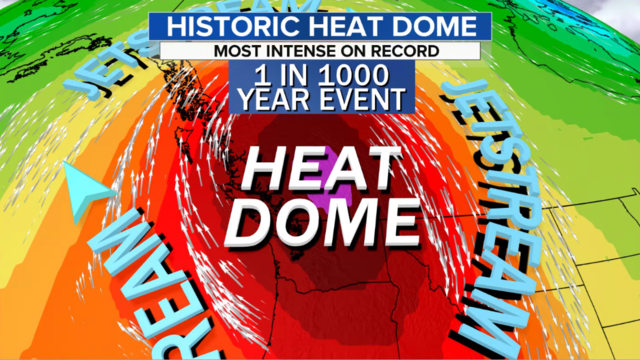

The California suit also takes a novel approach to damages, again informed by the suits that have come before it. Rather than peg damages to a particular extreme weather event, which can be tough to back up in court (in much the same way that one person's cancer is hard to blame on only one factor, extreme weather events are hard to connect solely to climate change, although attribution science can often reveal what percentage of an event's damage is attributable to climate change and there is growing consensus around the idea that climate change increases the likelihood of certain events as well as the resultant damage), the complaint seeks to create a fund that would be used both to deal with extreme weather events and to help the state and its residents adapt to and mitigate climate change. Again, all of those costs are currently being borne by taxpayers, this suit seeks to require the fossil fuel companies to foot their fair share of the bill. And it follows a model that's already been successful in California, where a $305 million abatement fund for lead paint was created in 2019.

Richard Wiles, executive director of the Center for Climate Integrity, which has been involved in most of the U.S. climate suits, called the California filing a "watershed moment" for U.S. climate litigation and "an unmistakable sign that the wave of climate lawsuits against Big Oil will keep growing."

In other situations where an industry has faced multiple suits from states and local jurisdictions—tobacco and opioids, for example—companies have eventually decided that fighting so many large legal battles at once is worse for business than settling. Particularly given how much they seem to want to avoid discovery, it's possible the oil companies will go that route as more and more cases are filed. It's hard to imagine that happening, but it's even tougher to envision them going along with a request that's front and center in California's suit: a jury trial.