Photo: View of the dais during the plenary on November 11, 2025. Credit: IISD/ENB, Mike Muzurakis.

In 2015, parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) signed the Paris Agreement at the 21st Conference of Parties (COP21). Crucially, they agreed to “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change.”

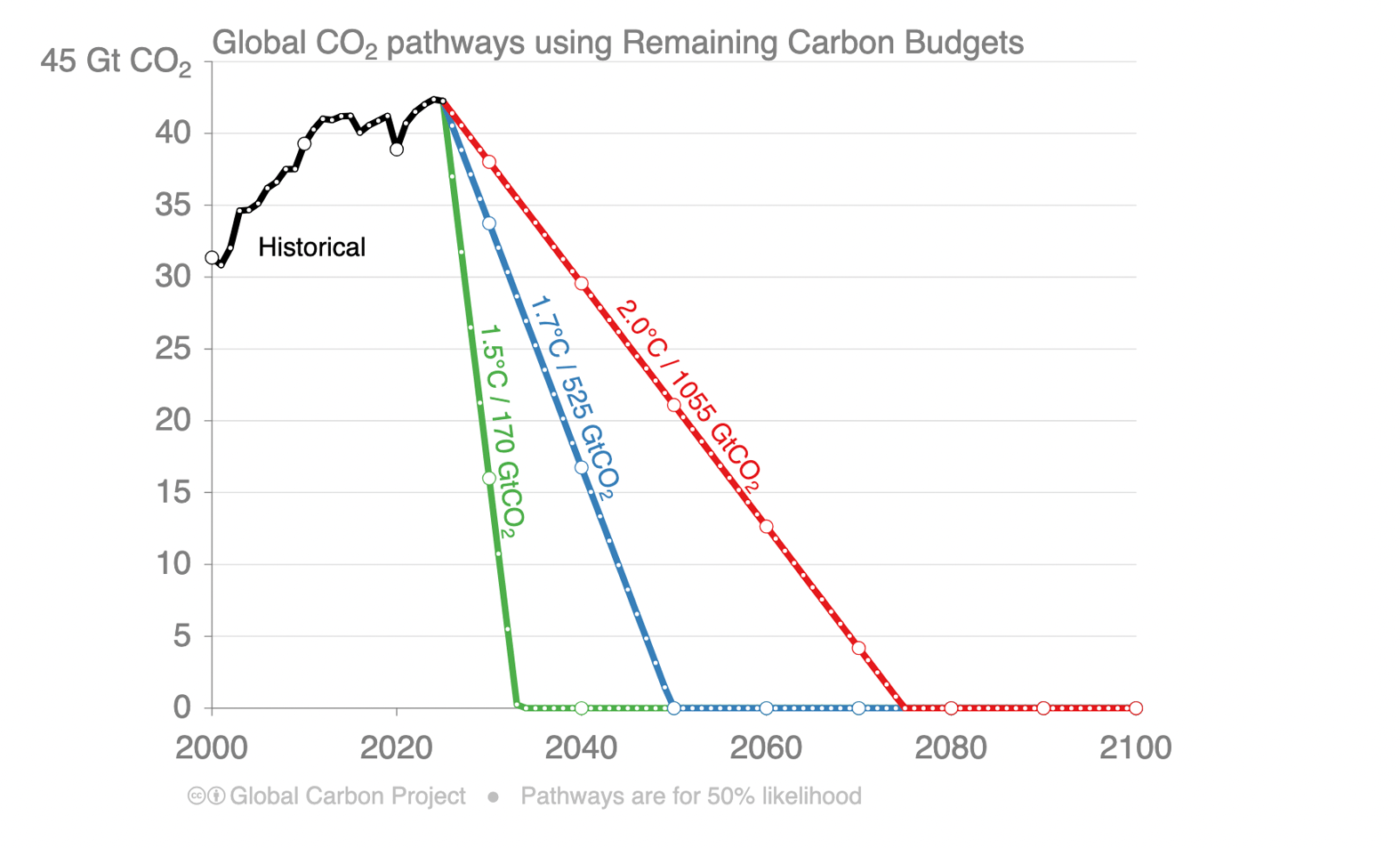

Ten years later, scientists say the goal to limit warming to 1.5C is a biophysical impossibility. The required levels of emission cuts are impossibly steep.

Chart by Robbie Andrew

At COP30, the Brazilian presidency is currently holding consultations on an item that was dropped from the official agenda: the 1.5C ambition and implementation gap. Some developing countries have sought the inclusion of the Paris Agreement text in its entirety i.e. a reference to 2C as well. India’s argument for the inclusion highlighted the impossibility of limiting warming to 1.5C and questioned the reliance on carbon dioxide removal (CDR) in mitigation pathways that allow temperatures to temporarily exceed 1.5C and then bring them back down known as overshoot scenarios. If CDR does indeed work at the required scale—there is no evidence at present to suggest that it will—studies have shown that it could entail other pressures on land-use and food security, primarily in developing countries.

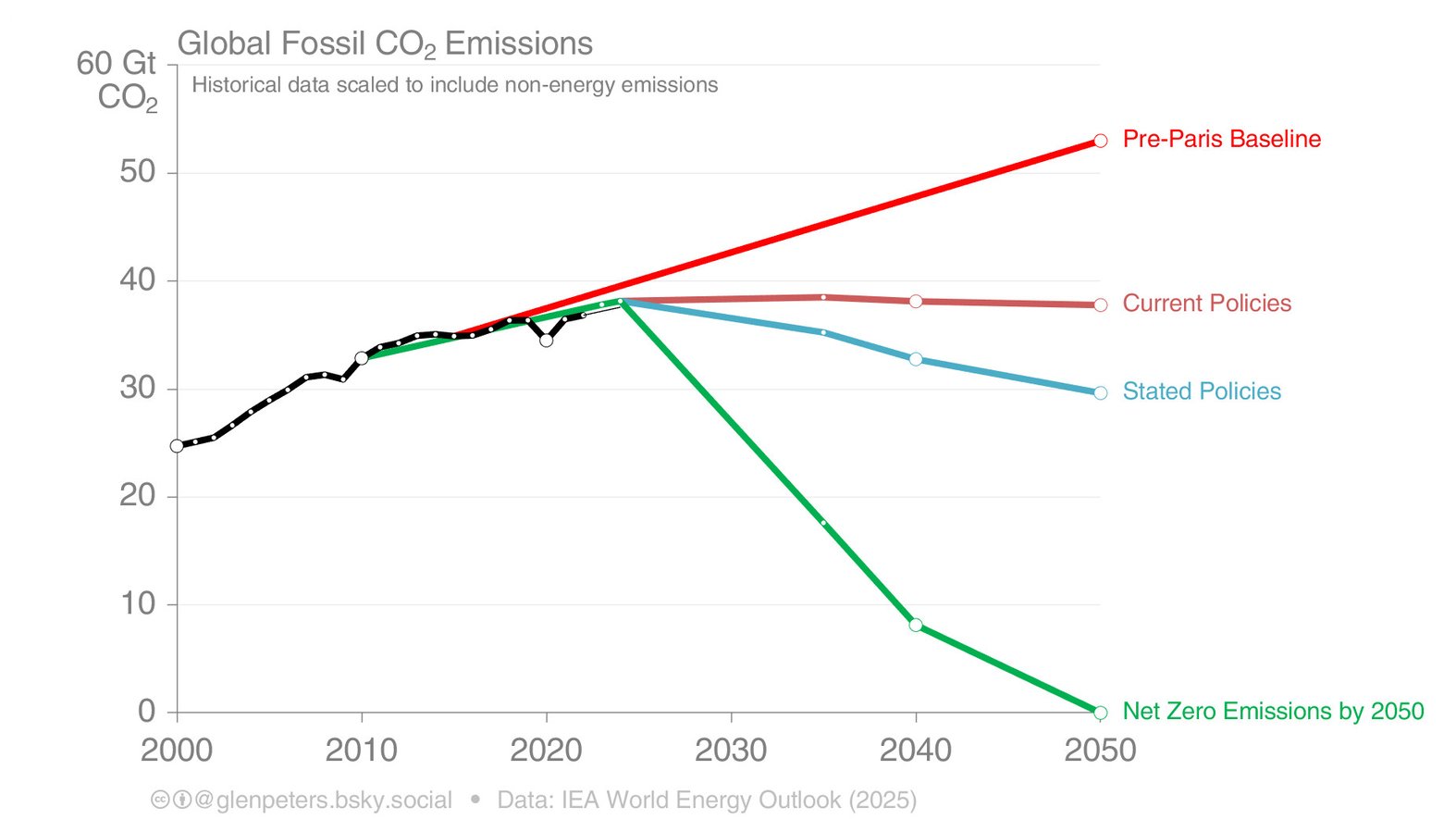

Given such realities and debates, Drilled interviewed Glen Peters, a climate scientist at the Centre for International Climate Research (CICERO) in Oslo, Norway about the Paris Agreement goals, the state of climate (in)action and where we go from here, and overshoot. Peters is one of the authors of the Global Carbon Budget 2025 which showed, among other things, that global fossil emissions are projected to rise in 2025 by 1.1%.

As a climate scientist, what is your assessment of where we are today in terms of achieving Paris Agreement goals?

The Paris Agreement has several goals, but I will focus on the mitigation related goals. In terms of global collective action, the world is not remotely on track. Global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, while the Paris Agreement says they should peak “as soon as possible…and to undertake rapid reductions thereafter” (Article 4). This is not happening. A peak in global CO2 emissions may be approaching, thanks to minor declines in net emissions from land-use change, but a peak in GHG emissions seems some years off.

There is positive progress in some countries, where GHG emissions are declining while the economy is growing, but these are generally developed countries with little or no growth in energy demand, aging and retiring fossil fuel power generation, making it easy to displace fossil fuels with renewable power. These countries would generally need to reduce emissions faster to be consistent with the Paris Agreement, particularly “on the basis of equity”.

The Paris Agreement embeds notions of equity, noting mitigation “will take longer for developing country Parties”. We see positive progress in terms of rapid growth in renewable technologies in a wide range of developing countries. These countries have rapid growth in energy demand, which still lags far behind the energy use per person in the developed world, and even rapid deployment of renewables can’t keep up with the growth in energy demand at this stage. It is worth noting that many developing countries deploy renewable technologies as they are cheap and fast, and climate and pollution benefits are really co-benefits.

Nevertheless, for collective action under the Paris Agreement, the simple arithmetic of cumulative CO2 emissions means that developing country emissions need to peak, and decline rapidly, even if developed country emissions went to zero overnight.

The overarching goal of the Paris Agreement is to keep the global temperature rise “well below 2C” while “pursuing efforts” to stay below 1.5C. The global average temperature is currently about 1.4C and rising at 0.27C per decade, which means the world will cross 1.5C within the next few years, probably by 2030.

The window remains open to stay below “well below 2C”, despite its vague definition, but this still requires peaking global emissions, with rapid reductions thereafter, to get global net zero GHG emissions in the second half of the century. Whether the world stays below 1.5C or 2C, the physics are essentially the same, mitigation just has to happen much faster for 1.5C.

All this does not mean the Paris Agreement is a failure. To me, the Paris Agreement is more a framework, which has the five year cycle of country pledges and review, followed by raising ambition. The world is off track, clearly. For Paris to work, countries need to raise their ambition.

At COP30, there are negotiations ongoing about addressing the 1.5°C ambition and implementation gap. If you had to provide scientific inputs to these negotiations, what would they be?

The 1.5C goal is basically breached. This was sort of clear from back in 2015, and now that failure needs to be acknowledged. The science is clear. Greenhouse gas emissions need to go down towards net zero GHG emissions in the space of decades. There is no easy way to do this, there is no obvious way to share the burden. Each country has to systematically push the barriers of political feasibility across all sectors of the economy. There is not really that much point arguing over the 0.1C differences at this stage. We know it is 1.4C, we know it is rising around 0.27C per decade, and that will continue unless emissions go down rapidly, as simple as that.

Rich countries like the U.K. and others in Europe, the U.S., Canada and Australia talk a lot about "keeping 1.5C within reach" at COPs, but their actions fall severely short. What do you make of this?

The Paris Agreement led to the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5C, which really popularised the net zero mantra. Essentially, it equated 1.5C and net zero CO2 emissions in 2050 with climate bonafides. Unless you had a net zero or 1.5C target, you just didn’t believe in climate. And so pretty much every country and company gave themselves a net zero target. Fast forward to today, and many are now starting to distance themselves, as they realise, “oh, this requires some work”. But it is hard to rewind. Since net zero and 1.5C equals “you are serious on climate”, then by giving up on 1.5C implies you are automatically a climate skeptic, at least politically. We need to get rid of this stigma and focus on what needs to happen. I guess countries and companies can bang on about 1.5C as much as they like, as long as they have a target and policy framework to get there. These targets need to be short term. If a developed country's emissions are not going down, say 5% per year, then they are not really in the ballpark to be consistent with below 2C, certainly not 1.5C. A developing country should be peaking and reducing emissions already. I don’t think countries have to have the full policy suite in place for net zero, but they have to have sufficient policies in place for emissions to be dropping rapidly. That is all that matters.

What is your assessment of climate action in developing countries today? Do you have any critiques?

In developing countries, the clean technology story seems to be going well and getting better. Developing countries are desperate for energy, and the penny has dropped, wind and solar are cheap and fast to deploy. Likewise, EVs don’t require oil imports. I suspect the surprises in the next few years will come from developing countries. However, whether emissions will decline is another story. It is easy to deploy lots of wind and solar, shuttering fossil fuel plants is another story. The challenge will be for developing countries to put the brakes on fossil fuel projects. If I was to give a critique, it would be that the world is your oyster, and you can do this without developed countries, and eventually outcompete them on cheap energy and manufacturing.

You wrote a commentary article last year saying "We no longer need scenarios with impossibly steep emission declines to 1.5°C, but more nuanced country-level scenarios integrating national circumstances and feasible ambitions." I have heard other scientists and researchers too refer to how enabling climate action at the national level is more ideal than simply scaling down ambitious global mitigation targets. Could you elaborate on the thinking behind this suggestion?

There are really two angles to this. First, Paris puts the control in the hands of the countries. It is the countries that deliver. Paris says to focus on the country level, and how they add collectively. Second, each country is unique, in every aspect, and only they know what works. What works in Australia, politically, technologically, socially, will be different to what works in Norway, which will be different to India, and so on. Each country has to find the transformation pathway that works for them, and makes them stronger and more resilient. This should also embolden local actors, to push their politicians, their industries, etc, to act.

Could you explain, in simple terms, what overshoot is? IPCC-assessed scenarios always had overshoot. But it seems to be dominating climate conversations only since the past year or so. And could you also explain the reliance on carbon dioxide removal in these scenarios?

Overshoot is where a temperature threshold is crossed (usually 1.5C) and is returned later. For example, 1.5C is crossed, temperature peaks at 1.7C in 2050, and then temperature comes back to 1.5C around 2100. This has always been how 1.5C, and many well below 2C, scenarios have looked. The overshoot, in many respects, was initially a quirk of scenario design, but has now become the only way to get below 1.5C.

In simple terms, temperature is related to cumulative CO2 emissions, which means that if global CO2 emissions are net zero, then the temperature would stay constant. So if net zero CO2 emissions were reached, and maintained, after 2050, and the temperature was 1.7C in 2050, then all-else-equal, the temperature would remain at 1.7C.

To get back to 1.5C requires net negative CO2 emissions, which is done by removing CO2 from the atmosphere, carbon dioxide removal.

To reduce temperature 0.2C would require about 400GtCO2 cumulative net negative emissions. If that started in 2050, and increased linearly, it would have to reach 16GtCO2 in 2100. We currently emit 40GtCO2. So these are big numbers. Since there are likely to be positive emissions from the hard to mitigate sectors (say cement, some aviation, etc), then additional carbon dioxide removal is needed, making these numbers even bigger!

There are a few other ways to reduce temperature in overshoot, such as rapid reductions in methane, and this effect reduces the size of the carbon dioxide removal.

The challenge with carbon dioxide removal is that it still requires rapid reductions in emissions, reaching net zero. There is no pathway that gets to net zero CO2 emissions without radical reductions in emissions. Even large-scale carbon dioxide removal is not a “get out of jail free card”.

This is one of the reasons that I think we should not focus so much on overshoot. It makes people look to 2100, think about fancy technologies that could remove carbon from the air, all of which we know are extremely expensive, and all the while, emissions are rising. Carbon dioxide removal is not useful if emissions don’t fall to zero. So eye on the ball, ensure emissions are reducing fast before obsessing on carbon dioxide removal and overshoot. It is just a distraction we don’t need now.