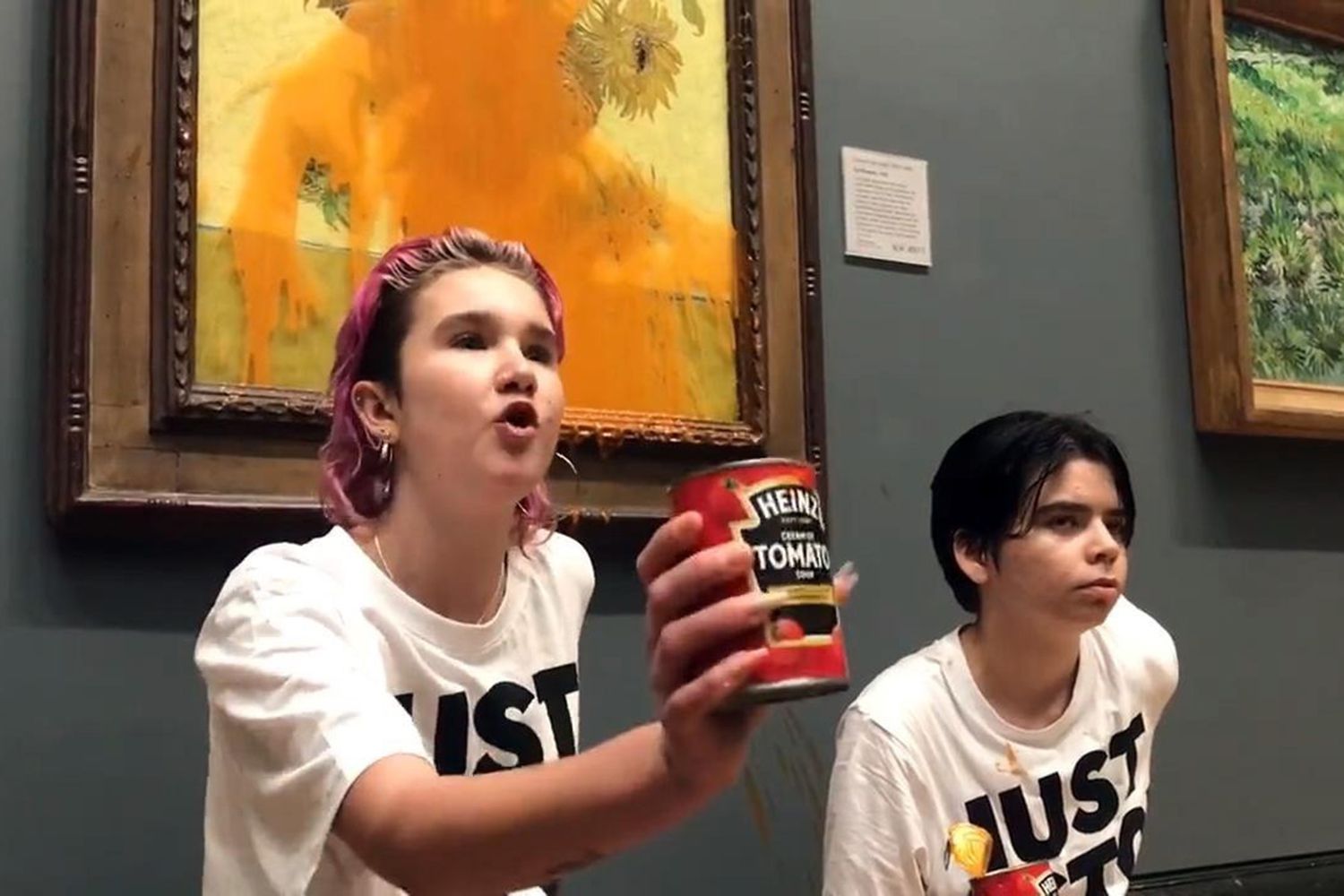

More than the protestors locked on to construction equipment, or the monkeywrenching along the Dakota Access Pipeline, or any of the massive visual protests Greenpeace has pulled off over the years, one action stands out as a flashpoint for how people around the world feel about environmental protest today: the tomato soup incident. Soupgate.

In October 2022, activists with the group Just Stop Oil in the UK threw tomato soup at Van Gogh’s famous painting, “The Sunflowers,” in the National Gallery in London, then glued themselves to the wall under the painting, asking onlookers “What is worth more, art or life?”

Within 24 hours most major media outlets had covered the protest in some way. Many covered it multiple times over the course of several weeks. It also inspired multiple copycat actions, with activists throwing mashed potatoes on a Monet in Germany, and pea soup on another Van Gogh in Italy. Those within the climate movement discussed the stunt and whether or not such actions were effective ad nauseum. Atmospheric scientist Michael Mann even commissioned a survey on it, and used the results to declare the tactic “alienating,” irking many of the social scientists who study social movements. The fact that the painting had remained intact—the soup only impacted the display case covering it—and that the activists had known that it would—didn’t stop various conservative commentators from decrying the use of “destructive” tactics and citing the incident as proof that climate activists are a “deranged cult.” Left-leaning media wasn’t impressed either. Mother Jones senior editor Michael Mechanic called the action “repugnant,” while New York Magazine writer Eric Levitz deemed it “flawed”.

None of those commentators had said anything when, six months earlier, the UK passed its updated Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, which was drafted and proposed explicitly as a reaction to disruptive climate protest. The bill dramatically restricts protest rights, enabling police to impose restrictions on where, when, and how loud a protest can be, and to arrest protestors who are occupying public spaces, hanging off bridges, or otherwise, vaguely, "intentionally or recklessly causing public nuisance.” The new law stipulates that damage to a memorial (like the statue of slave trader Edward Colston that was toppled in Bristol as part of Black Lives Matter protests) could result in up to 10 years in prison, while those protesting within the new “buffer zone” surrounding Parliament face increased fines and jail time. It also criminalizes being on private and some public lands, which although common in the U.S., where trespassing laws have been around forever, is less so in the U.K., particularly in Scotland, where the “right to roam” makes all land available for public use provided that right is not abused. Human rights organizations in the country have argued that this aspect of the law criminalizes a way of life for the many Gypsy and Traveller communities in the U.K. Though it was presented as necessary to deal with large, disruptive protests, the law is also applicable to one-person demonstrations. And perhaps most concerning, the law extends to the courts as well, restricting activists’ ability to justify their actions by explaining anything at all about why they acted or the urgency of the climate crisis. That restriction has civil rights advocates outside the climate movement concerned as well.

“Judges, in wanting to uphold the law, have tried to limit what the jury is allowed to hear,” Oscar Berglund, a senior lecturer at the University of Bristol whose research is focused on protest, said.”So defendants weren't allowed to give certain kinds of evidence, and weren’t allowed to mention climate and so on, that context wasn't allowed to be heard in court.”

“As we’ve seen with anti-terrorism laws, which were quickly used to go after climate protestors as well, it's absolutely the case that if you grant certain powers to the state to deal with one problem, they will use it to deal with other problems as they see fit,” Berglund added.

The U.K.’s anti-protest legislation was driven and enabled by exactly the sort of reaction to disruptive protest tactics that the tomato soup stunt elicited. In response to protests by the group Extinction Rebellion that routinely shut down roads and bridges, the think tank Policy Exchange, which has received funding from both U.S. and U.K. oil companies and lobbying firms, put out a report in 2019 called “Extremism Rebellion,” urging precisely the sorts of changes to policing protest that are now law. The report got picked up by various pundits and politicians, and the idea that Extinction Rebellion were dangerous radicals began to spread. At a summer party hosted by Policy Exchange in 2023, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak thanked the think tank for helping to draft the policing bill.

Even when they are explicitly tied to climate protest, protest-criminalization bills are not being created in a vacuum. It’s important to remember that they are coming not only on the heels of Indigenous-led pipeline protests in the U.S. and Canada, and increasingly disruptive climate protests in multiple other countries, but also in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, which began in the U.S. but quickly spread across borders. The line about memorials in the UK bill—which analysts there have noted is likely a response to the toppling of the slave trader statue in Bristol—is a perfect example. So is both the plan for and the resistance against the police training facility dubbed Cop City in Atlanta, where activists are protesting the increased militarization of police and the loss of crucial forest due to the development of a facility where officers will be trained in exactly the sorts of militarized, counter-insurgency tactics that are increasingly being used to suppress protest. Cross-racial organizing for both racial justice and climate action has increased dramatically in recent years; that threatens various powerful entities—from industries to politicians to police—and they are responding in kind.

While the reaction to “Soupgate” seemed over the top, it’s also not terribly surprising that people were upset by it, because shock was the point, according to Dana Fisher, a sociologist who researches protest and runs the Center for Environment, Community, & Equity at American University. Civil disobedience is meant to be disruptive and it’s a tactic that’s been used by multiple movements, including the suffragettes, the civil rights movement, and the anti-Vietnam War movement. “Most movements start out trying to work through the institutional political system, and what happens is they either die down because they give up, or they succeed, and then they give up, or they don't succeed, and more people join the movement, and more people get pissed off, and if they are not squelched by the powers that be, they tend to radicalize,” Fisher, whose book on climate protest Saving Ourselves comes out next year, said. “And you get this radical flank, which is the first folks to radicalize, doing more and more disruptive protests. Radicalizing historically means going to art galleries and not throwing tomato soup on glass coverings, but rather slashing art.”

She said radicalizing can also mean destroying property in some way, but it can also refer to less destructive tactics, like boycotts and sit-ins. “The point is to push those sympathetic to the cause toward taking action—not to get everyone out throwing soup at paintings, but to get them off the couch and to a protest, for example.”

“I recognize that it looks like a slightly ridiculous action,” Phoebe Plummer, one of the two Just Stop Oil activists involved in the tomato soup action, said in a video she posted shortly after the incident. “I agree, it is ridiculous! But we’re not asking the question, should everybody be throwing soup on paintings? What we’re doing is getting the conversation going so we can ask the questions that matter, questions, like is it okay that Liz Truss is licensing over 100 new fossil fuel licenses, is it okay that fossil fuels are subsidized 30 times more than renewables when offshore wind is currently 9 times cheaper than fossil fuels?”

Fisher said the tomato soup action was textbook “radical flank effect”: it inspired multiple other actions, got global media coverage, videos of it were viewed 10s of millions of times, and it got people talking about climate change for weeks.

If civil disobedience follows a predictable path, so too does the backlash to it. Historically, governments, industry, and law enforcement have attempted to paint environmental activists as out-of-touch outsiders, elitists. It’s a narrative that is boosted by the fact that white-led environmental groups have their own history of failing to take into account the demands of people of color and working class people — and continue to misstep at times to this day. One of the things that the fossil fuel industry does best is to exploit regular people’s genuine, and sometimes valid, critiques of activists to its benefit. By twisting those negative opinions, the industry can more easily demonize and criminalize its enemies. It also tends to react the most aggressively when threatened, which is why the latest wave of attempts to criminalize environmental activists is coming just as climate and racial justice movements are coming together in ways not seen in the past.

The reaction to the soup incident makes more sense in the context of not only the history of social movements but also the history of Just Stop Oil, which was spun off by Extinction Rebellion co-founder Roger Hallam for the sole purpose of engaging in disruptive, direct action protests, particularly once Extinction Rebellion announced a temporary halt to disruptive tactics in January 2023. The biggest critique of Extinction Rebellion and, subsequently Just Stop Oil, has tended to be around class. “Here in the UK, it’s working class people who will be most impacted by the climate crisis, and what you see in a lot of circumstances is working class people getting really angry about climate protestors,” Berglund said. “I don’t think that’s good for the climate movement, I think it has a potentially long-term damaging effect. If your enemy is the fossil fuel industry, you want the public to see you being dragged off the road by shareholders, not by the working class people who will be most impacted by climate change.”

The U.S. environmental movement has a history of being tone deaf on race and class, too. Between 1968 and 1972 when most of the big green organizations were created, “people were out in the streets fighting for social justice—you had the Black power movement in the streets. You had the women's movement that was emerging, the gay rights movement, the anti-Vietnam War movement. So even young white kids were putting out street heat. But the environmental movement wasn’t engaging.” Rev Yearwood, president of the Hip Hop Caucus and longtime climate justice activist said. “The environmental movement said at the very beginning, we are not going to be a part of that kind of movement.” The climate movement has just begun to shift that thinking over the past few years, Yearwood added. “At some point in time, they realized—and some have some haven't—we can't do this alone. We're not big enough or strong enough to beat the industry as a I say, a Birkenstock movement that's on the East Coast and on the West Coast. And so now they are at a point where they're literally trying to do a crash course on racism.”

Though it doesn’t always get it right, the climate movement is shifting, and more often than in the past, grassroots groups from the frontline communities most impacted are leading environmental fights, and the climate movement in general is getting better about incorporating racial justice demands with a push for climate policy. That shift is sparking increased backlash. It wasn’t until a broad cross-racial, cross-class coalition showed up to protest the Dakota Access Pipeline on the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation that the industry felt the need to draft “critical infrastructure” laws criminalizing pipeline protest, for example.

That’s because the increased intersectionality of the climate movement is making it more effective—inspiring a broad coalition of support, from labor unions to racial justice advocates—which also makes the backlash less effective. Mountain Valley pipeline protestors, for example, have frequently been accused of being “not from around here,” but the accusation falls flat because the primary resistance against the pipeline is local. “I would argue that it’s the Mountain Valley Pipeline that is not from around here,” scientist and activist Rose Abramoff said. “It's locals who don't want this pipeline going through their land.”

When Cancer Alley activists attracted some funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies this year to fight against the continued spread of petrochemical facilities there, the industry’s first line of attack was to label them out-of-state agitators who don’t represent the views or values of Louisianans. Shamyra Lavigne, who works with RISE St. James, the organization her mother started, has lived in St. James parish her whole life, as has her mother, and her mother’s parents before that. “ I find it humorous that they do not want outside money coming in, however these chemical plants are owned by foreign owners,” she said. Formosa, the company RISE blocked from building a massive plastic facility in St. James, is a Taiwanese company, for example. “So getting foreign funds is the name of the game when it comes to petrochemical industries,” Lavigne said.

In other countries, too, accusations of environmental protestors being outsiders or “foreigners” is a standard go-to. In Uganda, for example, those in favor of the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) are prone to saying that activists who oppose the pipeline are city folk from Kampala who don’t understand the benefits the pipeline will bring to the rural Hoima region where it’s being built in eastern Uganda. But those criticisms fall flat when protests are being led by people like Bob Barigye, a biology teacher who grew up in Hoima and has been arrested four times protesting the EACOP. "My activism is to go to the streets,” he said. “As the proponents of the pipeline are making documents, talking in seminars, for us, we hit the streets because we know this makes more impact.”

India has long used accusations of outsider or “foreign influence” to go after environmentalists there as well. “They are very clever about how they actually limit environmental activism,” Disha Ravi, co-founder of Fridays for Future India, said. “They're not attacking us in public, but they're being very strategic about the kind of tools they use.” Those tools include revoking certain licenses, making it impossible for activists to raise money outside of the country. Still, as Indian lawyers and activists are increasingly leading the fight against coal, it’s getting harder to make the case that it’s only foreigners who want to see India get off coal.

Critics have used whiteness and class privilege to discredit some climate protestors as well. And here again, sometimes that critique is valid, and activists would do well to center those most impacted by climate in their actions. But there’s also a long history of trying to dissuade those with privilege from using it on behalf of those who lack it. Historian and journalist Nick Estes said splitting off white allies is one of the ways that authorities are trying to break racial and class solidarity in the climate movement. “Since Standing Rock began in 2016, followed by the George Floyd protests in 2020, it has gone very quickly from police targeting Indigenous, Black and brown people to targeting any white people who dared to fight alongside us,” he said.

When people across the country went to Standing Rock to stand with the Lakota and Dakota people defending their land and water rights there, fossil fuel industry spokespeople and police highlighted the number of people from “out of state” as proof that the protest was staged or that protestors were paid. It was a false narrative cooked up to delegitimize the protest, but it was also ignorant of indigenous communities and activism. “The thing about Indigenous movements, in contrast to modern political movements or political parties, is that they're not movements of strangers, they’re movements of relations, a lot of people are familiar with each other or they're organizing according to their clan system or their, what we call, the societies that are created within traditional governance systems— male societies, female societies, warrior societies, all kinds of different societies that exist,” Estes said. In the case of Standing Rock, the Sioux, or Oceti Sakowin people, are located in what is today Montana, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Manitoba and Saskatchewan in Canada.

“And so after the defeat of Keystone XL, the Northern leg, there was a lot of people in Standing Rock who were paying attention,” Estes said. “So when I first went up to the camp, a lot of the people back home that we had worked with on the lower rural reservation issue were already there. Members of the Oceti Sakowin had their own little camp system set up. It was actually just uniting people on the ground. Our nation, the Oceti Sakowin, the nation of the Seven Council Fires. It was all proof that these things had never gone away.”

If they’re hard to get right, and guaranteed—even engineered—to piss off the public and ratchet up policing, why engage in more disruptive tactics? “Well, because they work for the desired goal, which is to get attention,” Fisher said. “I just went on TMZ Live to talk about the U.S. Open climate protest and the first question they asked me was why these activists would go to such lengths and I said, ‘Well because no one has ever asked me to come on TMZ Live and talk about climate protests before and here I am.’”

Many activists also say they prefer to engage in direct action because it feels like they’re accomplishing something tangible. “We're trying to stop this pipeline, and this is one of the most effective ways to do it, is to just get in front of and literally stop work on the pipeline,”Abramoff, who was recently arrested for locking herself to a drill at the Mountain Valley pipeline, said. “We stopped construction for about half a day.”

Indigenous-led protests have tended toward this sort of disruption as well, often setting up resistance camps on or near construction sites and blocking construction. If police seem to be particularly targeting Indigenous-led movements it’s not just because of garden variety racism, but also because, thanks to treaties that give tribes legal land and water rights, the disruptive protests of many Indigenous-led groups has been remarkably effective, from defeating the Keystone XL pipeline to igniting a nationwide resistance to pipelines with Standing Rock. “Indigenous movements are challenging a quarter of carbon and greenhouse gas emissions from the U.S. and Canada— two of the largest per capita polluters on the planet,” Estes said. “We're like 1 percent of the population here in the United States. It’s more in Canada but not that much more. We’re punching well above our weight class in terms of our impact on the future of the planet. And I think the fossil fuel industry recognizes that.”

Fisher said the unfortunate reality is that less-disruptive protests, even when they’re large, just don’t get as much coverage or attention. People getting arrested brings media and social media attention, which is why so many of the activists engaging in direct action are aiming to do just that. The March to End Fossil Fuels, during New York Climate Week, which organizers claim had a turnout of 75,000, only generated a couple of stories, for example. “But, then you go from that to the next day where we had a couple hundred people who blocked the Federal Reserve, and a hundred people got arrested. There were way fewer people, but that one got news coverage all over the place,” Fisher said.

That’s part of what radicalizes activists over time, according to Fisher, this feeling that the sanctioned pathways of resistance don’t often work. The vast majority of people don’t start out doing disruptive actions, but rather showing up to organized protests, and maybe campaigning and calling elected officials. Joanna Oltman Smith, who was arrested earlier this year for smearing finger paint on the display case protecting a Degas statue called “Little Dancer,” at the National Gallery in D.C., said she spent decades engaging in actions that broke no laws, from joining her local community board in New York to working with citizen lobbying groups like Moms Demand and the Trust for Public Land. “And I just started to feel like... the extreme weather events that were happening in my life were being caused by all of our manmade emissions and that the local politics wasn't up to speed in terms of coming up with solutions around that.”

Her first foray into more disruptive protest was what she calls “ silent, meditative witness in front of the BlackRock headquarters.”

“Occasionally I've been arrested there for nonviolent civil disobedience, things like protesting in the lobby after they ask us to leave or making a little bit of a challenge for people entering the building,” she said. The action in D.C. that Smith took part in with the group Declare Emergency, alongside fellow activist Tim Martin, “was my first time stepping up as an individual,” Smith said, “putting myself on the line to really do something that we knew would raise the alarm, that would pierce the bubble of mainstream media.” Smith said the action was planned not only for maximum media attention, but also to carefully avoid actually destroying any property. “We very deliberately used tempera paint that is otherwise known as washable finger paint that's used in nursery schools all over the world,” she said. Nonetheless she and Martin were indicted in May on charges that included “conspiring against the U.S. government,” a crime that comes with a maximum of 10 years in prison and a $500,000 fine. Their cases are still making their way through the legal system.

Part of the point of what researchers call the “radical flank” of any movement is to get the sort of reaction Plummer and Fisher talk about, to get people who are sympathetic with the cause to think, as Fisher put it “maybe I’m not going to glue myself to a road, but I’m going to get off my couch and go to a march, or get involved in electoral politics.” The radical flank’s job is to shift what’s deemed appropriate or possible in one direction or another; it’s a phenomenon known as the “Overton window,” named for the conservative strategist who first described it, and it can be applied to movements that shift public thinking toward either end of the political spectrum.

In many countries, you could argue that far-right ideas, for example, have shifted the entire political spectrum to the right more than civil disobedience has shifted things to the left in recent years. In Australia, it’s mostly been left-leaning Labour governments that have passed state laws criminalizing protest, for example, not conservative governments. Researcher Liz Hicks says that’s the Overton Window at work. “The conservative and industry position against climate activists is so extreme and ridiculous that laws repressing speech start to look like the moderate position,” she said.

Shocking, disruptive climate protests are an attempt to tug that center back in the direction of social justice. But it’s a tug-of-war that won’t soon end.

“As more people are disruptive, even engaging in non violent civil disobedience, law enforcement and counter protesters are going to emerge who are going to be violent against those protesters,” Fisher said. “It happened very clearly during the civil rights movement. And that was one of the reasons that a number of people who wrote about the movement say that the government started to respond, because sympathizers who were paying attention may have not supported the civil disobedience, but they absolutely were repulsed by the violence against these young Black Americans who were getting beaten up for sitting at a countertop and refusing to move, for example. That kind of violence initiates what we call moral shocks. Moral shocks are wonderful motivators to get people to do stuff absent of organizational ties and embeddedness in movements. People who care about the climate crisis, all of a sudden seeing these young people being harmed is going to motivate them to do something. Because they are going to feel that it is unacceptable and that is the kind of pressure that will be needed to actually get the kind of changes that are necessary.”

It’s a bitter pill to swallow, this idea that backlash to the point of violence is what may ultimately catalyze a response, or that anyone might be asked to sign up for getting punched in the face to get people to care.

Meanwhile, the concern voiced by climate-conscious observers over the tomato soup protest, that the action could turn off supporters, doesn’t seem to be holding up a year later. Fisher and her team collected data at the March to End Fossil Fuels during New York climate week in September, surveying 170 participants selected at random, and found that a shocking 95 percent supported civil disobedience—defined as intentionally breaking the law as part of a protest. 67 percent said they strongly support it, and only 5 percent said they neither supported it nor didn’t support it. “So nobody said they do not support these groups,” Fisher said, referring to groups like Climate Defiance, Declare Emergency, and Extinction Rebellion.

That’s particularly interesting given that only one percent of the participants who agreed to be surveyed had ever turned out for a large-scale climate protest before, and the New York march itself was a planned, permitted protest, so these were not by and large people who participate in civil disobedience themselves. “In terms of anybody arguing that people and organizations doing civil disobedience turn off people who are engaged in the movement from participating in the movement, this is absolutely showing that is not true,” Fisher said.

That may be because more and more people are experiencing climate impacts themselves. While the majority of folks engaging in disruptive protest are not from frontline communities, they have increasingly had some sort of personal experience with climate change. Fisher said 87 percent of the people she surveyed at the climate march in New York reported having experienced extreme heat in the past six months. 85 percent said they had experienced wildfire smoke. 60 percent said they had experienced more frequent and powerful storms, including hurricanes, typhoons, and tornadoes.

“We know that lots more people have experienced climate shocks and they have actually had personal experience with climate change,” Fisher said. “And this is evidence that the people who are experiencing it are doing more than just sitting on their butts complaining, or cleaning out their houses, or moving. They're getting out into the streets.”