This is the first story in an ongoing collaboration with The Intercept Brasil. The story is also available in Portuguese on their site.

Brazil wants to become a world leader in sustainable fuels, but in its eagerness to take on this role, the South American COP30 host may be falling into a major trap set by the agricultural industry. The country is allocating around $500 million in public funds to corn ethanol production—and the beneficiaries of this windfall are companies with a history of environmental and labor violations.

An investigation conducted by Drilled and The Intercept Brasil shows that six of the seven companies involved in corn ethanol projects financed by the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) over the last 12 months, or their subsidiaries, had a record of environmental violations or labor and land issues.

The only company that hadn’t had such a record began to build one shortly after its application was approved. The violations highlight the contradictions in the Brazilian corn ethanol sector's promises, which pitch themselves as sustainable while receiving billions of reais in investments as a climate solution.

BNDES guarantees that “all approved financing complies with current regulations, including from a socio-environmental, labor, and CO2 emission reduction standpoint”. But according to experts interviewed by The Intercept and Drilled, the public bank's actions are inconsistent, “reckless, and potentially irregular,” according to Bruno Teixeira Peixoto, a lawyer and legal advisor on socio-environmental and climate integrity.

“Economic and political bias often ends up overshadowing these assessments. Sometimes, certain agendas become more of a priority,” says Fábio Ishisaki, public policy advisor at the Climate Observatory. The BNDES stated that financing “the biofuel sector is part of the federal government’s strategy to support energy transition and decarbonization.”

The uncontrolled growth of corn ethanol production could lead to deforestation, warns a researcher from IEMA, who conducted a study with the Climate Observatory. (Photo by Mauro Zafalon/Folhapress)

The corn ethanol sector says it is sustainable because it promises to expand the production of grains that supply ethanol plants without deforestation, thus helping to contain the climate crisis by replacing fossil fuels with biofuel made from corn. The idea has the support of state governments, the federal government, and far-right politicians—and was brought to COP30 by the agricultural sector and the government as a “sustainable and scalable” solution to address the climate crisis.

However, according to an analysis by the Climate Observatory and researchers at the Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), the uncontrolled growth of corn ethanol production could indeed cause deforestation, increase greenhouse gas emissions during its production and distribution, lead to increased use of pesticides, and expand agricultural frontiers.

Even so, the sector has received a considerable amount of public funding, boosted by the enactment of the Fuel of the Future law, the country's main policy to promote decarbonization in the transportation sector and encourage the use of sustainable fuels by the Lula administration.

Since 2020, seven companies have applied for and received financing from the National Development Bank (BNDES) for corn ethanol projects. In total, R$ 3.31 billion was requested by them.

Most of this amount, R$ 2.5 billion (around USD 500 million), was financed by the National Fund on Climate Change, known as the Climate Fund. It’s part of the National Policy on Climate Change and earmarked for mitigation and adaptation projects. At least R$ 644 million had already been paid by the BNDES by August 31.

Since its creation, the Climate Fund has been used in 177 contracts for various sectors, totaling R$ 12.66 billion. The six projects linked to corn ethanol account for 19.7% of the total amount already allocated by the bank through this financial instrument. That’s well above the average of the other projects supported by the fund.

Among all Climate Fund operations, only 21 contracts exceed R$ 100 million, six of which are focused on corn ethanol. Four of these financing agreements, signed with the companies 3Tentos Agroindustrial, Coamo Agroindustrial Cooperativa, FS I Indústria de Etanol S.A., and São Martinho, are among the largest operations ever approved by the Climate Fund. Each of them contracted financing of R$ 500 million.

But the group of ethanol mill owners did not only grab funds with projects sold as sustainable. They have accumulated approximately R$ 10.14 billion in financing contracted by the BNDES in 22 years – including those from the Climate Fund. Of this amount, R$ 7.49 billion has already been released to the companies.

Although the first contracts date back to 2003, the largest volume of funds – around R$ 6.29 billion – is concentrated in projects signed since 2017, the same year that the Renovabio law, Brazil’s national biofuels law, was enacted. Of this most recent amount, R$ 4.02 billion has already been released by the BNDES.

Graph released by the National Union of Corn Ethanol (Unem) showing the sector's expansion. The entity declined to comment to the press. (Image: Unem/Press Release)

Brazil is currently experiencing a corn ethanol plant construction boom, with 24 plants in operation, 16 already authorized, and 16 announced by investors, according to the National Union of Corn Ethanol (Unem), an entity that represents the sector. This is not surprising.

The country, together with Italy and Japan, is leading efforts to establish a commitment to quadruple the production and use of sustainable fuels by 2035. According to sources at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, there is an interest in opening markets and positioning Brazil as a producer of sustainable fuels—particularly sustainable aviation fuel (SAF)—and not just a supplier of raw materials for their production in emerging markets.

In the leadup to COP30, Brazil recruited other countries to sign on as well and proposed that the other signatories adopt ambitious national policies for sustainable fuels and cooperate to, among other actions, accelerate the licensing of sustainable fuel projects and related infrastructure. To date, 19 countries have endorsed the document. The so-called “Belem 4X Pledge” has some worried that President Lula’s proposed “roadmap” to phase out fossil fuels will be “paved with biofuels” as one COP30 observer put it.

Corn ethanol fits into this scenario mainly because there is a decree in the country, 6961 of 2009, which vetoed the expansion of sugarcane cultivation and new sugarcane ethanol production facilities in the Amazon, Pantanal, and Upper Paraguay Basin, considered sensitive ecosystems. There is no such veto for corn.

Since 2017, corn ethanol plants have been concentrated in the midwest of the country, mainly in the Cerrado region of Mato Grosso. However, with the industry lobby opening the public funding floodgates, industrial plants and monocultures are moving up to Matopiba, an agricultural frontier formed by the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí, and Bahia.

Among the 16 new corn ethanol plants whose construction has been authorized by the National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP), there are two in Bahia, one in Tocantins, and another in Rondônia. Of those announced, there are two more in Bahia, one in Tocantins, one in Piauí, and two in Pará, in the Amazon.

Financing ignores companies’ environmental violations history

Among the minimum requirements for those who want to apply for financing from the BNDES, according to the bank's own website, are compliance with environmental legislation and fiscal, tax, and social obligations.

However, The Intercept Brazil, based on environmental data available on the Cruzagrafos platform, on Ibama's infractions website, and through the Access to Information Act (LAI), reveals that there are companies with a history of environmental violations that have been awarded financing.

Coamo Agroindustrial received R$500 million in approved funding for the construction of a corn ethanol plant in Campo Mourão, Paraná state. In 2018, in the same area, the company was fined more than half a million reais by Ibama for violations against the flora in the Atlantic Forest. The fine is listed as paid on the Ibama's website.

Coamo's ethanol plant project in Campo Mourão, Paraná, announced in May this year by the company. (Photo: Coamo/Press Release)

Cerradinho Bioenergia, on the other hand, had access to R$ 5 million from BNDES in 2024 to grow eucalyptus that will be used to supply a corn ethanol plant in Chapadão do Céu, Goiás state. In the same municipality, the company was fined in 2009 by Ibama for deforestation. The fine of more than R$1.3 million is still listed as awaiting payment or appeal in the federal agency's database.

São Martinho, another company on the list of seven beneficiaries of public funds from the BNDES, contracted financing in the amount of R$ 1.24 billion solely for operations related to corn ethanol – R$ 500 million of which came from the Climate Fund – for the construction of a corn ethanol plant and a silo in Quirinópolis, Goiás, and to invest in innovations at other plants.

The company has a long environmental and labor violations’ history. Between 2007 and 2008 alone, it was inspected by the Ministry of Labor and Employment, which found irregularities affecting sugarcane cutters in the workplace, such as inadequate meal areas, lack of protective equipment, and absence of periodic medical exams.

Even after several fines, São Martinho continued to violate labor standards, and was therefore sued by the Public Ministry of Labor. In 2017, it was fined for environmental damage resulting from the burning of sugarcane straw between 2007 and 2011 in Piracicaba, São Paulo state. In January of this year, it was fined R$ 5 million for compulsory dismissal of elderly workers.

FS, with US and Brazilian capital is the first in the country to have a 100% corn ethanol production plant, had R$ 500 million in financing approved by the Climate Fund to build its fifth plant in Mato Grosso, in the municipality of Querência.

The fourth had already been announced in 2025 in Campo Novo do Parecis city, and the first three were installed starting in 2017 in Lucas do Rio Verde, Sorriso, and Primavera do Leste.

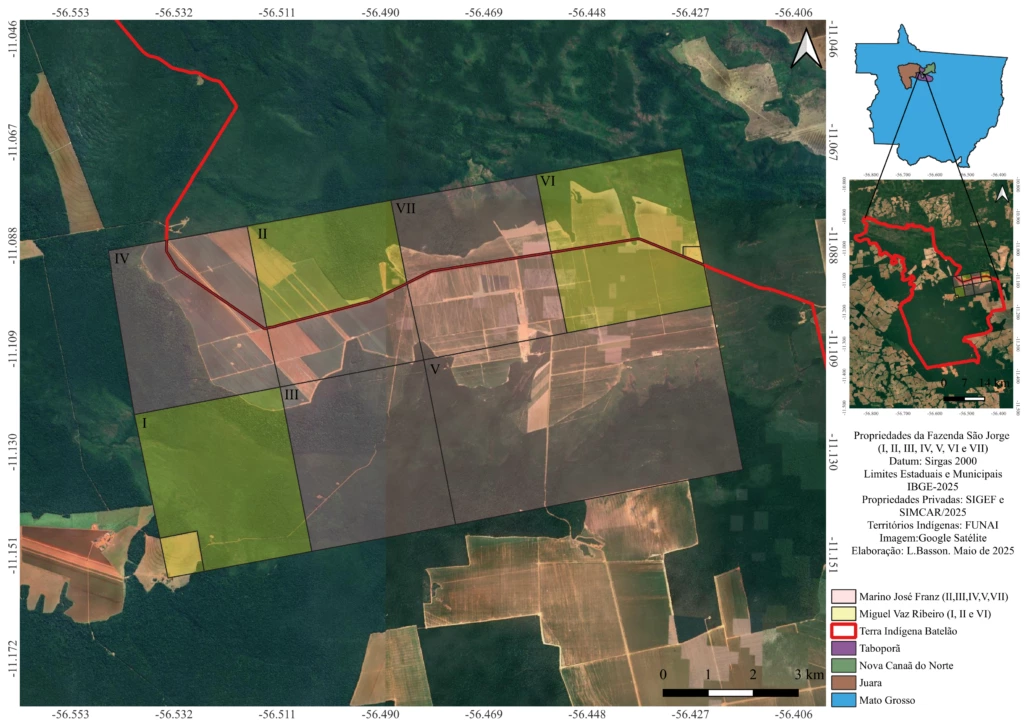

Marino José Franz, one of FS's partners, and Miguel Vaz Ribeiro, current mayor of Lucas do Rio Verde, in Mato Grosso, and also a partner in the company, have farms overlapping the Batelão Indigenous Land, in the Amazon region of Mato Grosso. The case is under federal court dispute.

In 2020, FS itself was fined by the Mato Grosso State Environment Secretariat for entering false data in forestry guides in Sisflora, the state's Forestry Product Marketing and Transportation System, according to documents obtained by The Intercept Brasil via public information requests. Forest guides are documents that record the origin, destination, and other information about wood, firewood, charcoal, and other products of plant origin. The false data consisted of license truck plates that did not exist.

FS has already been fined by the Mato Grosso Environment Secretariat for entering false data in forestry reports. The company has Brazil's first plant that produces 100% corn-based ethanol (Photo: FS/press release)

The technical report on the fine emphasized that this type of commercialization allows companies to “legalize” or “launder” products and by-products of illegal origin.

FS entered 15 false vehicle license plates into the state environmental agency's official system and was fined R$ 11,500. The company did not present a defense. As it paid the fine in cash, it received a 30% discount, paying less than R$ 10,000.

A recent Reuters article states that Brazilian prosecutors are investigating illegal use of native wood to supply corn ethanol production plants. FS has said that its 87,000 hectares of planted forest, including eucalyptus and bamboo, can supply all of its operations and expansion plans. The company’s U.S. partner, Summit Agriculture, meanwhile, is embroiled in various lawsuits over its efforts to seize land via eminent domain to build a carbon capture pipeline connecting corn ethanol facilities across multiple Midwestern states from Iowa to North Dakota.

3Tentos Agroindustrial, the only one of the seven companies on the financed list that had no environmental fines, was caught in July this year using trafficked workers in the construction of its new corn ethanol plant in Porto Alegre do Norte, Mato Grosso. The company requested R$ 500 million from the Climate Fund for this plant. R$ 200 million has already been disbursed for this operation.

Repórter Brasil reported that government inspectors rescued 563 workers from the company's construction site, the largest rescue carried out in 2025. The money for combating the climate emergency was used by 3Tentos in a project with unsanitary housing, no water, no electricity, poor food, and even debt bondage “with strong indications of human trafficking,” according to Repórter Brasil. After the case came to light by the media, the BNDES decided to suspend the funds allocated to 3Tentos.

BNDES stated that it is currently evaluating the explanations provided by 3Tentos, which may result in a request for the return of the funds already transferred to the company.

However, the bank did not make it clear whether the history of violations is an impediment to receiving funds. It only said that all the companies mentioned in this investigation “underwent a thorough registration analysis and no final judgments were found resulting from environmental and/or labor violations that would prevent the granting of financing.”

This analysis includes an assessment of social and environmental risks, in accordance with the Socio-Environmental and Climate Management Regulations for Operations. For the Climate Fund, the bank says it also requests a calculation of CO2 emissions avoided with the implementation of the financed project. “The BNDES's Social, Environmental, and Climate Responsibility Policy also applies to the biofuel sector,” the reply concludes.

According to lawyer Bruno Teixeira Peixoto, the BNDES has duties of due diligence, assessment, and ongoing monitoring of social, environmental, and climate risks under the rules and regulations of the Central Bank of Brazil (Bacen) and the National Monetary Council (CMN).

Although for the BNDES a history of fines, penalties, or legal proceedings under appeal is not a legal impediment to financing, Peixoto considers this to be a serious point of risk exposure to which the bank is subject. “It is not prudent to rely solely on the existence of final judgments in infractions and convictions,” he says.

Financing companies with a history of environmental violations, explains Ishisaki, from the Climate Observatory, can pose risks to the bank, although it is not an impediment to granting credit. “Environmental and climate risks are not only risks of damage, but also reputational risks. If the business is seen to have a reputational risk, this must also be considered in the portfolio,” he explains.

Ishisaki points out that the bank can be held liable for financing an activity that causes environmental damage, but that there is currently a gap in this process due to the time it takes for lawsuits analyzing the guilt of companies to be processed.

For Peixoto, the bank should explain how the history of environmental fines impacts the risk rating of projects and companies to be financed. “Did this history of companies raise the project's risk rating? If so, what concrete measures and countermeasures were required and even met by the beneficiary companies?” asks the consultant. The BNDES did not respond to our questions about what documents it required.

FS Bioenergia partners have farms overlapping the Batelão Indigenous Territory in the Amazon region of Mato Grosso. The case is currently under federal court review. (Image: Lidielze Basson)

For Peixoto, the 3Tentos case is evidence that the BNDES’s own monitoring and follow-up mechanisms are flawed, since the case came to the bank’s attention via the press.

“The responses provided by email [to The Intercept] so far do indeed reveal that the BNDES acted in a manner that was, at the very least, reckless and potentially irregular,” says Peixoto. In the case of financing through the Climate Fund, the consultant points out that there is “an inconsistency” on the part of the BNDES in releasing large sums without clear monitoring of the direct and indirect benefits in terms of climate goals.

We also contacted the companies mentioned in this report directly. São Martinho stated that “the financing obtained from the BNDES strictly follows the legal and regulatory criteria and requirements applicable to each operation.”

The industry's main argument in defense of its sustainability claims is the use of second-crop corn to supply the mills, but the government does not certify grain suppliers and relies on data provided by ethanol producers. (Photo: Mauro Zafalon/Folhapress)

Cerradinho Bioenergia clarified that it sent the BNDES all the necessary documentation requested for analysis of its eligibility to receive funds from the bank. It also reported that the fine imposed on the company has been contested in an administrative proceeding with Ibama since 2009. The area in question remains embargoed.

3Tentos stated that the case did not occur at the company's facilities, “but at an external accommodation under the responsibility of the construction company hired to carry out part of the work,” and that it had not been fined.

FS and Coamo did not respond to our questions.

The new Saudi Arabia and its contradictions

Before COP30, mill owners helped build a narrative to position Brazil as the Saudi Arabia of biofuels. Selling Brazilian ethanol as sustainable is fundamental to this narrative.

The main argument of the agricultural sector regarding the sustainability of corn ethanol is that the grain used in the manufacture of biofuel is from a “second crop”, that is, planted in the same area where soybeans were harvested. This, in theory, would prevent further deforestation to open up areas for cultivation, one of the main causes of greenhouse gas emissions.

Data from the National Supply Company (Conab) show that Brazil achieved a historic record for corn production in the 2024/2025 harvest, with 141.1 million tons, 27% more than in the 2023/2024 harvest, driven by an increase in the area planted with second-crop corn. For the 2025/26 harvest, projections point to an expansion of the cultivated area in both the first (+6.1%) and second corn harvests (+3.8%), says the agency.

In 2024, 20% of Brazilian ethanol was already made from corn, equivalent to 7.55 billion liters – sugarcane, the dominant feedstock for ethanol in Brazil, generated 29.7 billion liters, according to data from the 2025 National Energy Balance.

The National Biofuels Policy, Renovabio, created to expand biofuels in the energy matrix, does not certify the corn producers, only the mill owners who refine the corn into ethanol. So there’s nothing in place to ensure that the corn is always a “second crop.”

The ANP has a technical report with procedures for tracking the origin of fuel raw materials. However, the information is entered by the biofuel producer and the intermediary that supplies the grain—such as a warehouse, trading company, or grain dealer. They can be audited, but they have to guarantee the origin of the raw material, which means that, in practice, the government is dependent on the information provided by the market itself.

The sector has at least two events at COP30, one of which is within the Blue Zone, where official negotiations, the Leaders' Summit, and national pavilions are located. (Photo: Unem/Press Release)

Although corn ethanol is a biofuel that emits less greenhouse gases than petroleum-based fuels, when it positions it as “sustainable,” the agricultural sector ignores how corn production can lead to increased land use for planting. Corn yields more liters of ethanol than sugarcane—one ton of corn produces between 370 and 460 liters of ethanol, while one ton of sugarcane produces 70 to 80 liters of ethanol—but the grain requires much more land to be cultivated: 1 hectare of sugarcane cultivation produces 6,800 liters of ethanol, while the same area of land with corn produces between 2,300 and 2,500 liters of biofuel.

A study by the Institute of Energy and Environment (IEMA), in partnership with the Climate Observatory, shows that it is possible to expand biofuel production in Brazil without deforestation.

Considering the additional amount of biofuels needed to meet domestic demand in 2050, within the context of an economy that eliminates more carbon than it emits—that is, a carbon-negative economy—the study projected an increase in the production of ethanol, biodiesel, green diesel, and sustainable aviation fuel, and how much additional land would be needed to produce their raw materials: sugarcane, macauba, soybeans, and second-crop corn.

The study considers only the use of 100 million hectares of areas already occupied by degraded pastures identified by MapBiomas, “without the need for any additional deforestation or competition with food production.”

For corn and sugarcane ethanol alone, the study predicts a total of 53.8 billion liters of this biofuel in addition to the 37.3 billion liters produced in 2024 to supply the domestic market in 2050.

To reach this amount, using 100% second-crop corn—planted in the area where soybeans were harvested—53 million hectares of land will be needed in addition to the 3 million used in 2024.

This represents almost all of the 56 million hectares of degraded pasture that the study identified as available for agriculture in general, which includes the production of raw materials for biofuels, the production of planted forests, such as eucalyptus, used in power generation, and food production. The remaining 44 million hectares would be used for the recovery of native forest and the recovery of degraded pasture into productive pasture for livestock. To accommodate all agricultural demands in this scenario, according to the study, deforestation would be necessary—which dismantles the agricultural narrative that second-crop corn will not have to deforest areas to meet ethanol demand.

“Corn appears to be a kind of lobby by those who already produce soybeans to create new demand: they produce soybeans, soybean meal, oil, and now corn as well,” says Felipe Barcellos e Silva, a researcher at IEMA and one of the study authors.

“From a socio-environmental perspective, the increase in the use of biofuels is viewed with caution, since their large-scale production depends on extensive areas of monoculture of sugarcane, corn, soybeans, among other crops,” warns the study by IEMA and the Climate Observatory.

The expansion of corn planting for ethanol production would also lead to an increase in the amount of pesticides used on crops, say researchers at UFMT. Brazil is already the world's largest consumer of pesticides, and Mato Grosso, the epicenter of corn ethanol production in Brazil and home to three biomes of fundamental importance to the planet—the Amazon, Pantanal, and Cerrado—is the largest consumer of pesticides in the country.

When analyzing the continuous use of pesticides in the case of second-crop corn planting, researcher Márcia Montanari, from the Center for Environmental Studies and Worker Health (Neast) at UFMT, states that this practice impoverishes the soil from a mineral and biological point of view.

“Fertilizer contains a lot of heavy metal chemicals, such as cadmium and lead, which contaminate the soil and groundwater. You amplify the overload of this soil and increase the need to use more and more chemical inputs. This promotes the spread of contamination,” explains the researcher.

Although the agricultural industry claims that monocultures are less harmful to the environment than oil, they still cause problems, Pignati points out.

“The production process [of corn and sugarcane ethanol] is quite dirty, and people say it's clean energy. It's clean at the end of the chain,” he says. "If you take into account deforestation, planting with intensive use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers, which also contaminate water, air, rain, animals, breast milk, blood, urine, and which causes a series of diseases, from acute to chronic poisoning, both alcohol produced from sugarcane and that produced from corn is one of the dirtiest forms of energy there is.”