If you don't work in media, perhaps it has escaped your attention that several hundred reporters have already been laid off this year in the U.S. alone. Just off the top of my head (and I am definitely missing some), The LA Times, Vox, WAMU, National Geographic, and Vice all announced massive layoffs in the past couple of months.

I have been seeing that news and talking to lots of laid-off reporter friends while also running my own small independent nonprofit news outlet, submitting grant proposals for funding, fielding questions from a lot of folks in philanthropy about media, and working on a whitepaper about the media landscape and where climate philanthropy could and should slot into it, so I have more thoughts than usual on this subject. Strap in folks, we're connecting a lotta red threads on the murder wall today, it's gonna be a long one.

Live footage of me right now.

I'm old enough to have had the great honor of getting a real-live lecture from the great Ben Bagdikian when I was a university student. I've read The Media Monopoly multiple times and The New Media Monopoly, and watched as everything Bagdikian warned about has come to fruition and then some. I read Manufacturing Consent during those years too, and recently revisited it. Both very worth a read in this moment, but to paint with the broadest of brushes here, the gist is that control of the media has shifted into fewer and fewer hands over the years and that mass media is used (often willingly so) as a propaganda tool by various corporate forces to help them circumvent democracy.

Climate coverage is the absolute clearest example of this. Especially coupled with the increasing amount of advertorial content that mass media outlets explicitly create for polluting industries. More on that in a minute. Let's start with the 1970s...

In 1970, Herb Schmertz, VP of Public Affairs for Mobil Oil, worked with The New York Times to create the advertorial. I think we need to pause for a moment here to grasp what a massive shift this was, for people to suddenly see weekly editorializing from a corporation in the nation's largest newspaper. Around the same time, Schmertz got the Mobil brass to agree to sponsor a new show on PBS: Masterpiece Theatre. Apparently they went to dozens of potential sponsors before hitting up Mobil and no one saw what Schmertz did: an opportunity to affiliate their brand with elites, with culture, with intellectualism. Schmertz talked later about how the partnership with Masterpiece helped establish Mobil as "the thinking man's oil company." Also important to understand here is that a key part of Schmertz's strategy was the creation of a persona for Mobil and a push to get people to think of the company as a person (this is not my analysis, it comes from Schmertz's own speeches, interviews, and writing on this subject). Schmertz came from a background of political campaigning and he felt that companies should be engaging more in the "marketplace of ideas."

By 1972, Mobil was not only running weekly advertorials in the NYT, but also had branched out to multiple other publications. Schmertz had revamped Mobil's entire comms strategy around this persona he had created and the practice of what he called "issue advertising." They weren't advertising gas or motor oil anymore, they were advertising ideas and policy positions. And it was going so well they figured they ought to branch out into TV. So Schmertz worked with some TV producers to create TV versions of some of his favorite Mobil advertorials. But when he went to place them on the big three networks (this was before cable news was really a thing, and looong before streaming), CBS and ABC turned him down flat and NBC said they'd only run the spots with major edits. The problem, according to all three networks, was that these ads were dealing with controversial issues of public concern, issues their news reporters were covering, and they didn't want to confuse audiences or broadcast propaganda.

Schmertz tells a similar story from this time about The Wall Street Journal in his book Goodbye to the Low Profile, in which he offers advice for corporate propagandists. He talks about a meeting at The Wall Street Journal offices (this is pre-Murdoch), a meeting he had demanded because he felt the paper's coverage of the energy industry was unfair to oil companies. And he says he got through just one of the ten or so bullet points he had prepared for the meeting before the paper's editor Frederick Taylor, got up and said, "Everything you're saying is bullshit," and walked out.

This, to me, even more than the moment when Exxon decided to go from researching climate change to lying about it, was such a decisive moment in the history of how we would go on to grapple with the climate crisis. Mass media at the time actually stood up and said no to corporate propaganda. And within a few years, that would disappear entirely. Mobil played a major role in that shift. Schmertz and Warner were looking at this pushback—especially from the major broadcasters—and they started to freak out a bit. They saw this as not just a one-off issue with ABC and CBS but as a threat to their new political strategy, and to the future they were confident it would deliver. So they went all-in on attacking the networks and positioning their refusal of Mobil's ads as a free speech issue. They started making speeches to business groups and doing interviews with various outlets about this new threat against corporate free speech. And they started looking for litigation that could create more legal protections for that speech. They threw their support behind Bellotti, a precursor to Citizens United that opened the door for corporations to do political advertising. When I talked to Brown University environmental sociologist Dr. Robert Brulle about this years ago he described Bellotti as a watershed moment in the history of "corporate personhood" in the U.S.:

"I don't think people really appreciate how big of a deal that was in shifting the rules of speech in the public space that now suddenly corporations could use their budgets, which are many times larger than individuals', to advocate their position in the public space. And as a sociologist, I would say that what this did was it allowed for a systematic distortion of the public space in that it gives corporations basically a loudspeaker to amplify their voice above everybody else's. And in a media environment where there's many, many competing voices, the ability to get your message out repeatedly over and over and over again in opposition to other voices, is enormously influential in getting your viewpoint to be part of the public discussion and eventually become part of the taken-for-granted worldview."

Mobil went on to support multiple other cases, and Exxon continued that work after acquiring Mobil. In 2003, seven years before the landmark decision in Citizens United that would fully make corporations people and money speech, Exxon filed an amicus brief in another really big free speech case, Nike v. Kasky. This was during a time when Nike was taking a lot of flack for using sweatshop labor and to defend against it, it was putting out a lot of videos and statements really trying to cast a more positive light over labor conditions in its non-U.S. factories. An activist in California, Mark Kasky, sued Nike under California's consumer fraud protection laws. He won and the case was appealed, eventually all the way up to the Supreme Court. In a very rare move, the court opted not to rule, declaring the writ of certiorari improvidently granted (in plain English: they decided they should never have agreed to hear the case in the first place). But Exxon's brief is nonetheless very interesting in the context of the history of corporate free speech and, relatedly, what's happening with media today. [Also just a side note here: Ted Olson, the attorney who would go on to argue and win Citizens United, weighed in on this case too; he was Solicitor General of the U.S. at the time and got special leave to weigh in. His firm, Gibson Dunn, is currently making this exact argument in dozens of climate liability cases.]

In its brief in Nike v Kasky, Exxon argued that when companies are speaking on "matters of public concern" (and yes, they do list "global warming" as an example), they "merit the highest level of First Amendment protection." The brief argues that Nike's speech on globalization, like ExxonMobil's speech on global warming and other corporations' speech on whatever issues impact their business, is actually "petitioning speech" not "commercial speech" and therefore not subject to fraud laws. We made a whole podcast miniseries on this that you should check out, but for our purposes today it's important to understand that, beginning with Mobil Oil in 1970, the fossil fuel industry made a concerted and well-funded effort to make mass media its propaganda arm in every way possible.

Then everything went digital. When the Internet first came about, for a very brief moment, it was largely a communications tool of, by and for the people. And corporations freaked out. I spoke a few years back with someone who was working for a management consulting firm at the time who told me that her Fortune 500 clients were all desperate to figure out how to buy and control that first wave of "influence" on the internet. Which reminded me of another thing Herb Schmertz said that always really stuck with me (yes, I'm obsessed). In a briefing he wrote for the American Management Association about Corporations and the First Amendment in 1978, he described the weekly advertorials Mobil ran in the New York Times as "pamphlets" and connected them to the very first uses of the printing press in the U.S., which was for people to print off their political ideas as pamphlets and hand them out to people on the street corner.

Schmertz positioned Mobil's takeover of the NYT editorial pages as just another step along that path when in fact it was more of a smothering of everyone else's pamphlets. With the Internet, too, you had all these individuals sharing their lives and their thoughts online and then corporations came in and drowned them out. Why? Because really they don't want individuals influencing anything. And then of course the same progression has happened with social media and influencer culture. For a hot minute there were individuals just sharing original thoughts or perspectives, then corporations took over and now if you want to be an "influencer" (a top answer to the "what do you want to be when you grow up?" question these days), you're mostly gonna be influencing people to buy some company's product or ascribe to some billionaire's ideology.

Big Tech has had plenty of other terrible impacts on media, too, stripping out publishers’ ability to monetize content at all and driving them to the brink of bankruptcy only to be picked up by a private equity fund that sells off the parts and delivers big payouts to a couple of top executives. As the great and recently laid-off tech reporter Brian Merchant put it (on Twitter — I know, I know!): “Big tech really has won. Google monopolized search & socials promised reams of traffic. So digital media organizations began catering to their whims; tailoring stories to SEO, pivoting to video—and letting big tech horde the ad revenue. Now we're just handing the stories directly to them.”

And here's where we get to the role of philanthropy in all of this. And a little bit of #storytime too. I've been reporting on climate and related areas since 2003. During various periods of my life, I reported on cleantech and green business for Forbes and The Wall Street Journal, the fossil fuel industry and the fracking boom for Inside Climate News, extreme weather in California for The Washington Post, worked as managing editor of the nonprofit Earth Island Journal, and covered climate and health for The Guardian. At some point 7-ish years ago, I was driving around listening to NPR in my car and saying to myself "I wish I could work for radio!" And then thinking well, I probably could, I bet there's a member station near here that I could volunteer at to get some training. So I went home, sent an email with the subject line "Would you like an over-aged intern?" to my local NPR member station—which was in Reno, Nevada at the time—and waited for a reply. The news director there wrote back and said she generally had a tougher time finding people with reporting experience than training people on audio and that I should come on in. So I did and I wound up doing an internship for a couple of months, and then they hired me on as a staff reporter.

I loved it, but I also quickly realized what every radio reporter knows: that so much great tape never makes it on air, that you collect hours worth of anecdotes and characters and deeply personal stories and then have to whittle it down to four minutes for a news feature that conveys all the facts people need to know. At the time, the first season of Serial had just recently come out and everyone was obsessed with reported narrative podcasts, myself included. A colleague of mine (and still dear friend Julia Ritchey!) and I made a storytelling podcast called Range, focused on what we called the New American West, covering everything from brothels and cowboy poetry to Tesla fanbois. I caught the podcast bug big time and as a lifelong climate reporter, I wondered why there wasn't a narrative, Serial-style climate pod.

Then, some life events set me on a new path. I loved my community radio reporter job, but it paid $19/hour and my babysitter charged $18/hour. So when I found out that I was unexpectedly pregnant with a second kid, two months after my husband had lost his job, I had to shift gears. I quit the radio station and took a lucrative project management gig at a marketing agency my friend ran. It was in San Francisco and I had to be in the office at least two days a week, so when my baby was 4 weeks old I started making 4am drives to San Francisco, pumping along the way, working that day and the next, then driving back to make it home by midnight. I started freelancing again too, to make extra money. And I kept going with the podcasts, because I felt like I needed just one thing that I actually enjoyed doing in my work life. Of course that's when I got the idea for the climate podcast I wanted to make.

I don't know where to put this, so I'm going to stick it here: throughout all of this time and still today, people are constantly pitching me stories and then getting mad if I don't cover or publish them right away. The general consensus seem to be that I am spending my days in bed watching TV, just waiting for that one pitch to come in so I can hop to and rev up the ol' publishing machine. Honestly, this seems to be how a LOT of people think media works, including many of the people funding media. It is not. At any given moment, I am working on at minimum 6 or 7 investigations and it's usually more like 10. It's a damn miracle I reply to email at all, frankly.

At any rate, for one of the three freelance gigs I was doing while also making podcasts and doing a full-time day job (this was 15 years into my "career," just to orient us all), I was covering a climate liability hearing in San Francisco. The judge had requested a "climate science tutorial" and I got there extra early to make sure I could be in the courtroom. All the characters were there: the smarmy oil company lawyers, the goofy scientists, the activists in their #ExxonKnew t-shirts, the eccentric judge...I thought aha! I'll make a true-crime podcast about climate change. The Exxon Knew story had broken a couple years prior, thanks to the work of journalists Neela Bannerjee, David Hasemeyer, and Lisa Song at Inside Climate News and Suzanne Rust, Sarah Jerving, Katie Jennings and Masako Melissa Hirsch at the Los Angeles Times and the Energy and Environmental Reporting Project at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. But it seemed to me like the general public had not wrapped their heads around it; it had not made enough people's heads explode as much as it had mine. I thought maybe if it were presented in a familiar narrative structure, and if people could actually hear the voices of the folks involved, that might do the trick. So I pulled together a list of all the researchers named in all of the documents, cross referenced it with obituaries and set about trying to interview whoever was left.

So, what does this have to do with philanthropy? A few things: One, philanthropy funded the reporting that eventually became the Exxon Knew story, and it was nonprofit researchers who uncovered that Exxon had donated its corporate archive to the University of Texas at Austin, and pointed journalists in its direction. Once the stories were published, it was climate foundations that funded the litigation that leveraged that reporting, including the case I was reporting on. Sitting in that courtroom in San Francisco, I didn't know any of that yet, I just had what I thought was a good idea, but I was also broke so I needed someone to pay for it.

I pitched it to all the media companies that were making nonfiction narrative audio at the time, and heard the same thing from all of them: it was a good idea, but they just didn't think there was a big enough audience for a climate podcast, no matter how narrative it was, to warrant the budget. At the time it was not uncommon for the budget of a slickly produced narrative podcast to be $300,000 or more per season. I knew in my bones that they were wrong on every front – there was an audience, and I thought the show could be made well for less. So I set my sights on grant funding, and eventually secured a $50,000 grant for what I thought was going to be a limited run, one season and done podcast: Drilled.

Couple things to note here: $50,000 is a lot less than $300,000, yes? Remember how I said I knew I could make it cheaper? Yeah, well not that much cheaper. And I was still in the same dire financial straits as before. In fact during this time, our car—which I was using as a studio, because kids are loud, studios are expensive, and cars make great studios—got repossessed, taken right outta the driveway. I learned how to make lentils stretch for weeks, how to do a bit of light check fraud when I needed groceries I couldn't afford, and just how little sleep I could get and remain functional.

Nonetheless, Drilled's launch was hugely successful. Our first season drew more than a million listeners, so we proved the audience part. But more importantly, we gave loads of other people a way to understand climate accountability. The climate-as-a-crime framework has been widely embraced now, it's informed the approach of several documentaries, copycat podcasts, and climate verticals at multiple outlets, but it was new at the time and it helped a really important story—the origins of climate denial—make sense to people.

It also meant that we could sell ads and start doing some production work for other folks, which meant new revenue streams. Then a nonprofit offered us a larger grant to build out a website and a reporting team, and do more seasons, which I enthusiastically accepted. But when they began talking regularly about Drilled as part of their campaign, doing ads featuring our content without running them by us, having conversations with production companies about optioning the show (without talking to me), and pushing for us to cover certain things or approach the stories we were doing a particular way, I felt like I had to make a decision between editorial independence—which seemed to me like the entire reason our work had any value in the first place—and financial stability. I sent a check back (not the full amount because some of it had already been spent, and I think we've established already here that I didn't have any money), and told them I didn't think it was going to work out. It wasn't a big conflict, there was no animosity, at least on my end, just a case of differing expectations and my not being aware enough to establish clear boundaries before signing a contract. I chalked it up as a learning experience and figured I would either get a different grant or find a way to replace that grant with earned revenue. My husband had started a new job, so he had income by this point and I felt confident we'd figure it out.

Two weeks later, my dad hung himself and then Covid hit. A month after that, my husband lost his job again (because of Covid). Then the editor I had hired had a major health scare. I don't really have it in me to fire someone in a pandemic, and especially not someone who's also going through a completely unrelated health emergency. Also I was probably avoiding grieving my dad, so I did what I always do in these situations, which is just work more. I freelanced my ass off to pay her and pay our bills and keep the trains moving. I landed a couple of big production contracts, and it was a ton of work but I figured I could hack it. I had been grinding it out for years, what was a little more grind?

Amidst all that, we made another hit season. This time about the long history of the PR industry and the integral role the fossil fuel industry played in shaping it, as an early and major client. Where the climate denial season had been informed by previous reporting, the PR season was sparked by social science research from folks like Dr. Brulle, as well as Melissa Aronczyk at Rutgers, and Naomi Oreskes at Harvard, plus whistleblowers at various agencies (most of whom I can't name, but Christine Arena, former Edelman VP, is an outspoken advocate and her insight was tremendously helpful). Building on that research and insight, we did our own reporting and research, heading to archives, talking to experts, and piecing together a history of fossil fuel's century-long propaganda war. And again, that work sparked new advocacy campaigns and follow-on reporting.

Then, just as all these new projects I'd agreed to work on hit a fever pitch, my husband got a job offer we couldn't afford for him to turn down, but it required working away from home every week. Which meant I would be solo pandemic parenting, including homeschooling (not by choice, the schools were shut), while also working more than I ever had in my life. For months, I woke up at 2am every day, worked til 8am, got my kids sorted with Zoom school, worked in hour long chunks through that, made them lunch, hung out for a bit after "school," made them dinner, then worked again til we all went to bed at 9pm. After a year of that, desperate and severely sleep-deprived, I hired other people to do tasks I would normally do, quietly burning through half my husband's paycheck every month to keep the business going, a bad move that, yes, still comes up in arguments. I couldn't back out of contracts, including the one new grant I'd taken on to support the launch of a spinoff show focused on the stories behind the nearly 2000 climate cases making their way through courts around the world. And again, we pulled it off. That show won the Covering Climate Now award for podcasts and the one we were producing for another company got a Peabody nomination. It also played a material role in producing evidence that dissuaded the Supreme Court from getting rid of the Indian Child Welfare Act.

The entire time, I could never convince a foundation to fund what anything actually cost or to fund things for more than a year at a time. No one could understand why "a podcast" would cost much to make, never mind that I was also writing dozens of pieces a year for every outlet under the sun, or that we were compiling primary research that was then used in litigation, Congressional hearings, and lots of other people's reporting. Or that we were accomplishing these major narrative shifts over and over again.

In speaking to the brilliant Meaghan Parker (outgoing head of the Society of Environmental Journalists) about this recently, she wondered if perhaps the metrics foundations apply to other types of projects should be re-thought for media work, or even just chucked altogether. In the past year the great folks at Doc Society have taught me a whole lot more about impact measurement, and it's made me think metrics are possible but I still think they should probably be re-thought. I have to explain how podcast downloads work every time I speak with a funder, for example, and even then it doesn't really matter because I could have an episode with five downloads but if one of those people is a Senator who then uses that information to craft policy, that's a huge impact that's not captured by any metric whatsoever (plus all the other non-pod stuff I already mentioned).

At the same time that I was chronically struggling to make ends meet as an independent climate reporter, I was increasingly being drawn into conversations about "strategic communications" in the climate space because Drilled was such a success story. More than once I put travel costs for one of these funder meetings on a nearly maxed-out credit card and crossed my fingers that it would ultimately pay off. Over the past two years I have given the same presentation over and over again to climate foundations, walking them through my very thorough documention of the time and effort the fossil fuel industry puts into things like "narrative work," how much they lean on emotion and standard narrative tropes, how ready they are with a story for every situation. The sheer volume of money they spend on media buys, advertising and PR.

When I ask people who are very interested in climate and media why they aren't funding newsrooms directly, I hear one of two things—either people will admit that they simply can't convince their boards to fund something where they had so little control over outcomes, or they say that this or that outlet wouldn't take their money because of concerns about the appearance of bias.

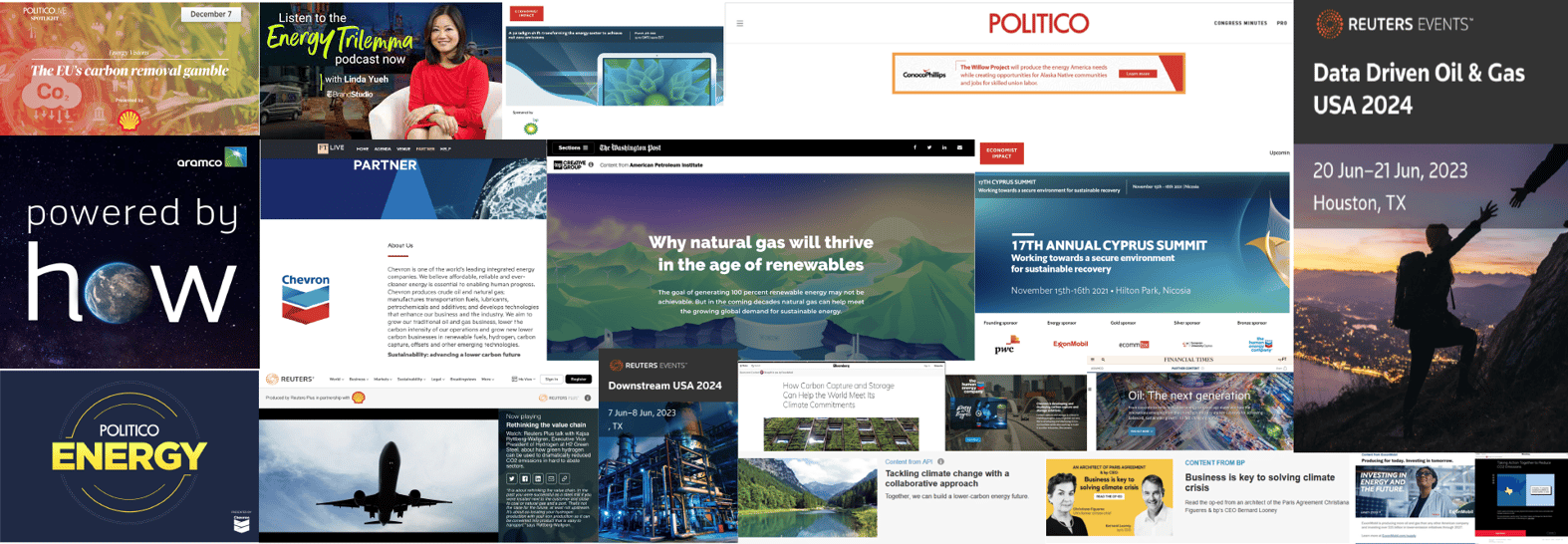

Which is pretty rich when you consider that The New York Times took in more than $13 million from Saudi Aramco alone from 2020 to 2023. Because yeah, surprise! The fossil fuel industry has not stopped investing in media, nor has it pulled back on any of those initiatives our boy Schmertz started back in the 1970s. On the contrary, it's gotten much worse amidst the transition to digital. News media never did figure out the right business model for digital, where advertising didn't work the same as print. The only answer to those missing revenues has been to lean increasingly further into the corporate propaganda business. Today, almost every major media outlet has an internal brand studio that crafts editorials, videos, even events and entire podcasts for advertisers, many of which are fossil fuel companies. Check out the report we did with DeSmog for all the data on this, but the likes of Politico, Reuters, Bloomberg, the NYT, the Washington Post, and the Financial Times are all creating content for oil companies that directly contradicts what their climate reporters are publishing. And we know from peer-reviewed research that at most one-third of people can actually tell the difference between advertorial content and reporting.

After seven years, we finally have support from some organizations that truly get it, that understand the value of keeping reporters on the climate accountability beat long term (shout out to William M. Kohler Foundation, Earth Percent, KR, FILE, and Doc Society). But I am still grinding it out fundraising year after year, while also running both a print and an audio outlet, managing partnerships with national and international outlets, managing an international reporting team working on cross-border climate reporting, handling all the promotion and marketing, doing a mountain of reporting and writing myself, hosting the podcast. Oh yeah and I still have those kids :) There's got to be even a slightly easier way to do this, no? When young reporters ask me how I've been able to carve out a niche for myself, my honest reaction is...have I? Because I still feel like I'm going to drop dead any minute.

I'm currently working on a white paper about media and where climate foundations fit into the landscape (commissioned and paid for by a foundation, yes!). As part of that I'm doing the same amount of research that I would do for any reporting project – talking to dozens of people on all sides of this question to deliver a clear understanding of the landscape and what is stopping so many outlets from doing rigorous reporting on climate — because I really freakin' care about making it possible for dedicated reporters who are passionate about this beat to be able to do this work in a sustainable way. In the course of that work (which I'll share here when it's done!), I've realized that most climate foundations' investments in media seem to be informed by the opinions of one middle-aged PR guy they spoke to a decade ago; no one seems to have bothered to understand how media works from people who actually work in the industry.

The approach climate foundations have taken toward journalism is also driven by a deep-seated fear of losing control of the story. Which is a function of how philanthropy works—the money is supposed to go toward furthering a particular mission; if you can't guarantee that an activity will do that, that you'll be able to measure and report on positive impacts, it's almost impossible to justify the investment. So in many cases, rather than fund reporting, climate foundations are funding nonprofit research or communications work that competes with reporting, efforts that enable foundations to control what's being researched, how that research is framed, and even which outlets ultimately run the story, which is what makes it so appealing. But guess what? It also makes it possible for newsrooms to cut back on their already meager investments in investigative journalism. Which isn't to say nonprofit research or comms efforts aren't important, they absolutely are, but not as a replacement for journalism. As I see tweet after tweet announcing wave after wave of layoffs—layoffs of great reporters who do some of the best work out there on climate—I can't help but feel infuriated by it all and deeply annoyed by the shortsightedness of a "strategy" that's cannibalizing the very outlets everyone loves to shout out in their annual impact reports. The only way to get consistently good climate reporting is to invest in reporters who can stay on the beat. That's it. It's very straightforward. And yet...

I couldn't find a way to make ends meet working a staff reporting job, so I jumped ship and started my own thing years ago. But it hasn't been that much more stable or predictable out here on my own, despite the fact that by every conceivable metric, the work has been very successful. This is the first year that I've been able to comfortably hire people on long-term contracts – long enough to really move the needle on some big investigative projects. But it's still tough to see what the next year will hold.

All of it has me thinking that solving this problem, answering the question of how to support consistent, independent reporting on climate that serves the public interest, is absolutely critical to getting to a place where we can adequately confront the climate crisis (also, bonus! pretty necessary for a healthy democracy).

While climate funding has largely concentrated on projects that compete with cash-strapped newsrooms and independent reporters for resources, fossil fuel funding in media is largely focused on ad buys that undermine the credibility of all climate reporting and bring the mainstream media ever further under its control. Ironically, foundations' fear of losing control is in many ways ceding control to the fossil fuel industry, which has invested heavily in not just influencing mass media but shaping the structures of it to suit the industry's needs.

This Week on the Podcast

A few years ago, Season 5 of Drilled told the decades-long saga of the attempt to hold Chevron and Texaco responsible for oil dumped in the Ecuadorian Amazon. We talked in that season about former Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa's attempt to get the world to pay to keep oil in Yasuní National Park in the ground. That attempt failed, and drilling began in the park in 2016. But opponents to it never stopped fighting and last year they got a measure on the ballot about banning drilling in what's called the ITT Block of Yasuní, an area where drilling particularly threatens biodiversity. 60% of voters opted to stop drilling there. It was heralded as a major win around the world. But reporter Macy Lipkin found that the truth on the ground in Ecuador is a bit more complicated.