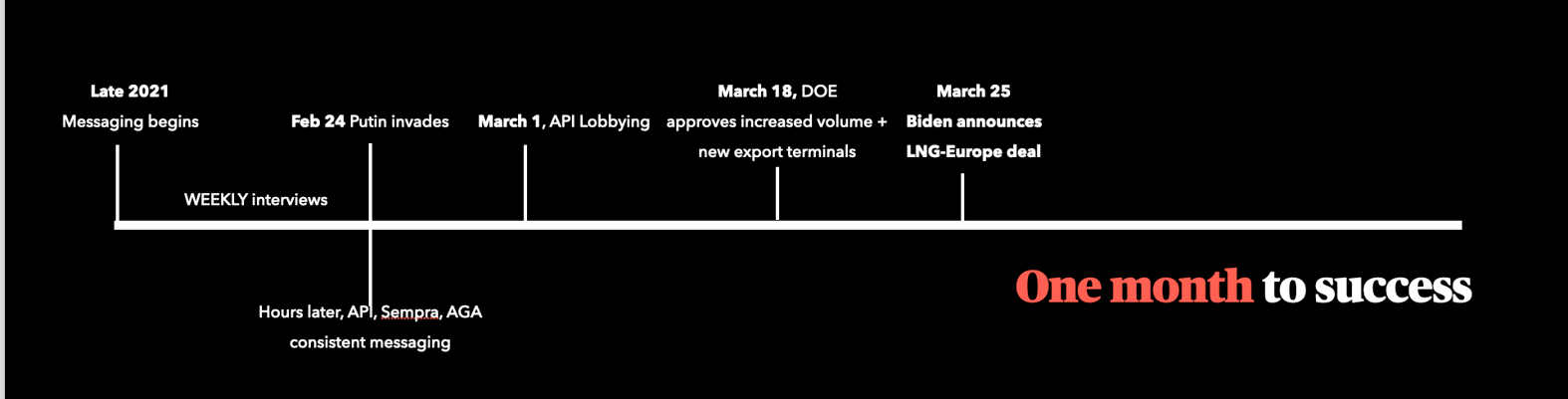

Long before Putin invaded Ukraine, the U.S. fossil fuel industry was preparing to turn Russian aggression into a boon for the gas industry. For months leading up to the invasion, the industry was busy highlighting the need for the United States to increase production and the damage that the Biden Administration's climate policies (of which there were none at the time) was doing to the industry.

Within hours of the invasion on Feb 24, 2022, gas industry spokespeople from Sempra, the American Gas Association, the American Petroleum Institute and more were pushing out remarkably consistent messages via social media and cable news, particularly these three:

By March 1, 2022, just five days after the invasion, the American Petroleum had submitted its lobbying laundry list to the Department of Energy, including asks like:

By March 18th, the DoE was in fact swiftly approving most applications, and by March 25th, Biden was announcing a U.S.-European Union liquefied natural gas deal that the Trump administration had tried and failed to get done back when Sempra Energy's Dan Brouillette was Energy Secretary: 15 billion cubic meters in 2022, with a standing order for 50 billion cubic meters a year until 2030.

One month exactly from invasion to making the industry's dreams come true. It's a breathtaking example of disaster capitalism.

In the year since, the industry has further capitalized on Russia's invasion of Ukraine. The U.S. fossil fuel industry alone has locked in 45 long-term contracts and contract expansions for LNG since the start of the war, according to research by Friends of the Earth, Public Citizen and BailoutWatch. That’s a major increase from the 14 such contracts signed in 2021. In Europe, despite announcements from most EU countries of a ban on Russian gas and oil, only two countries (the UK and Lithuania) have actually stopped importing the stuff. In 2022 Russia was the second largest supplier of LNG for the EU.

Russian LNG imports to Europe have actually increased since the invasion of Ukraine; they were up by 46% between January and September 2022 compared to 2021. Yet, the EU's urgent need for non-Russian gas continues to be used to justify more LNG terminals, more drilling everywhere, and the need for American companies to lock in 20- and 30-year contracts. Some of those contracts are so long that European politicians are seeking to ban them because they would block most countries' ability to meet their Paris Agreement commitments.

Meanwhile, Biden's Department of Energy continues to fast-track approvals for LNG terminals, most recently the Alaska LNG Project, which would emit 10 times as much greenhouse gas pollution as the much-protested ConocoPhilipps Willow project. And at a meeting of the energy ministers from the G7 countries in Japan this week, Japanese ministers are pushing for increasing the use of LNG, with no indication that Biden Administration officials will push back.

When burned, gas produces fewer CO2 emissions than coal or oil. But it produces large quantities of methane, a greenhouse gas that is 80x more potent than CO2 over 20 years. And those emissions aren't just generated by the use of gas, they're emitted throughout the extraction, refining, and distribution process. Because methane is both intense and short-lived, experts say tackling methane emissions in the near term could give the world a much-needed window in which to figure out how to transition away from fossil fuels. Dramatically increasing methane emissions, on the other hand—which is what the current attempt to lock in gas for decades will do—could exacerbate near-term climate impacts.