Nostalgia for a supposed “golden age” of the past. Fear of sharing power with women and people of color. Apparent contempt for ordinary people. Determination to resurrect the myth of American exceptionalism. An apocalyptic conviction, even giddiness, that civilization and the planet are inevitably doomed.

These bleak convictions unite many far-right politicians and their techno-libertarian backers. But has this powerful coalition found an unexpected ally in the mainstream media?

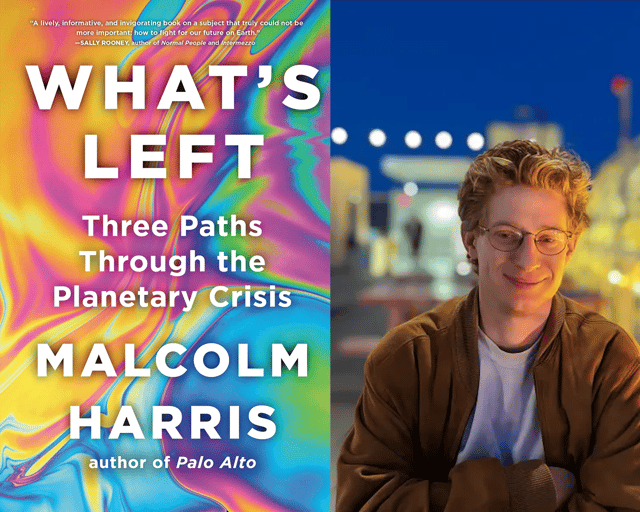

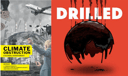

In her new book Apocalyptic Authoritarianism: Climate Crisis, Media, and Power, University of Toronto media scholar Hanna E. Morris argues that whether they realize it or not, some climate journalists, obsessed with preserving a self-determined “moderate center,” are deploying some of the same tropes and reinforcing some of the same narratives as the extreme right. Even as they see themselves defending democracy and confronting the climate crisis, these media elites might be contributing to a prize sought by both the MAGA right and the fossil fuel industry: Preventing the emergence of a hopeful, democratic, and class-defying movement against climate change.

Earlier this month, Morris spoke with Drilled about the who gets to choose which climate solutions are “right” and which ones are “wrong,” what the media’s divergent treatment of the Green New Deal and the Inflation Reduction Act reveals about its entrenched biases, and why a sense of fatalism and inevitability seems to pervade so much mainstream climate coverage.

The conversation below has been condensed and edited significantly for clarity and accuracy.

Want to listen to an extended version of this conversation? Check out today’s podcast episode:

I think a good place to start would be two terms that you mention throughout the book: “apocalyptic authoritarianism” and “apocalyptic environmentalism.”

“Apocalyptic environmentalism” is referring to largely environmental thinking that emerged out of the Cold War era. This was an era when there were a lot of existential anxieties. There were real fears of nuclear warfare. And there was, for the first time, the Apollo 17 photos of Earth—often referred to as the “blue marble” photos—which showed the Earth floating [in] this vast expanse of darkness. Coupled with this fear of total annihilation with nuclear warfare, seeing this vulnerable, tiny planet floating in this vast expanse of darkness ignited a global environmental movement that imagined an apocalyptic scenario of a total destruction of Earth by humans.

Why I introduced this term of “apocalyptic authoritarianism” is, around 2016, there became a lot of national anxieties at the same time as not feeling any stability in terms of the direction of the nation, not knowing what’s going to unfold, not knowing how to respond. There [also] became really notable impacts of climate change. So there was this pairing of national anxieties with climate anxieties that reached a crescendo around 2019, where there was a spike in climate coverage for the first time. This is the year that scholars [said] climate change “trended.” Media coverage [of the climate crisis] was up [73] percent compared to 2018.

With this feeling of total instability, total anxiety, there became this imagining of a certain group as being “saved.” That’s those who are more traditional figures of power, those who claim to be able to right the ship and return on the stable path of Manifest Destiny [and] bring the nation out of this. And this led to a lot of reactionary posturing that united the traditional figures of power on the right and in the center around this common enemy of the so-called “new” New Left that was blamed as further suspending the nation and the world into total crisis, and positioned these traditional figures of power that I call “visionary sage figures” as the ultimate authorities that must be followed.

That’s not a very democratic way of responding to or reckoning with the very real political and climate threats that are occurring.

One of the arguments you make in the book is that a lot of the mainstream media, including a lot of climate journalists, are quite obsessed with, or at least nostalgic for, the past—this sort of “golden age,” as you describe it, where journalists were revered and powerful and the arbiters of what is true and what is not. How [would] you would describe the state of climate journalism today?

I have to say that it’s not a good time to be a journalist, as you probably know.

I can confirm!

It’s been longstanding pressures on journalism with movements towards social media and digital media and a struggle to adapt to these new business models. Also, a drop in public trust because of Trump calling the U.S. press the “enemy of the people” and a lot of direct attacks on journalists.

So it’s completely understandable [to try] to find a way out of this. Among more traditional journalists writing for really big publications, legacy presses like the New York Times, whose publisher, A. G. Sulzberger, for example, consistently has been writing public-facing pieces buckling down on needing to protect these traditional modes of doing reporting.

Instead of thinking about how to move away from hyper-capitalistic business models and figuring out how to have collectively owned newspapers, more support for independent newspapers [and] local journalism, there’s [a consensus] among these big, important national presses, this buckling down on, No, we need to continue how we’ve been doing this. The same goes for reporting practices. Sulzberger consistently says, The nation needs us. They need journalists. This romanticization of journalists being a stabilizing force.

“Democracy dies in darkness.”

Exactly. Again, journalism is extremely important and is under attack. But there could be, I argue in the book, this moment of trying to grapple with how to do journalism differently and include more people [and] come out of communities. Instead of having this identity of civilizing “others” [who] need to listen to journalists, making that a bit more equitable in terms of the power dynamics.

I looked at [climate] journalism between Trump’s first election in 2016 until his second election in 2024. This was when climate journalism in the U.S. took off for the first time. In these news stories, and also in editors and writers and publishers commenting about their perception of journalism today, there was this romanticization, this nostalgia, for a post-World War II period. This was a period when—in stories that we tell ourselves—the U.S. was considered to be a global stabilizer and global leader.

Part of that was journalists seeing themselves as not just bringing people together on the national level, but also a global level, too. U.S. journalists providing this force of reason, this democratizing force. U.S. journalists were respected during this period in a larger way, in a more fundamental way, than maybe they are now. So it kind of makes sense why there’s this nostalgia for this period.

But this was a period when there was not a lot of diversity in newsrooms. There was not a lot of robustly democratic processes for decision-making. Women, people of color were not included. This was before civil rights movements and pro-democracy, revolutionary politics of the late 1960s, 1970s. This romanticization of this [post-World War II] period in time is quite striking and illuminating. I argue that it closes off imagining ways of trying to figure out what to do in this Trump era, and how to respond to climate change in a robustly democratic way.

One of the themes of the book is, who gets to decide what are the “right” solutions to climate change? What are the “wrong” ones? One of the places that plays out is how the media covered the Green New Deal, compared to how it covered the Inflation Reduction Act.

The Green New Deal was proposed and developed by a progressive contingent during Trump’s first presidency. The Sunrise Movement was a youth-led climate justice movement that was founded in 2017 but built upon decades of community organizing around climate justice and visions for how to have a national-level response to climate change in a way that centered justice and democratic decision-making.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, progressive congresswoman of color—this is important, too, because the climate justice movement is really led by young women of color—was elected in 2018, running on the Green New Deal as a core policy commitment. Her election was an upset. It was quite unprecedented. She ousted a longstanding Democratic Party figure, and she showed how there was desire for a different way of imagining American politics.

In 2018, before the Green New Deal was picked up by the national press, there were surveys [of] the key tenets of the Green New Deal: including lots of people in deciding how to respond to climate change and what energy transition would look like; [involving] working-class oil and gas laborers in imagining how to transition to renewable energy; centering historically marginalized groups—young women, Indigenous people, Black and brown people. Eighty-one percent of Americans supported these key tenets of the Green New Deal. That’s a striking statistic.

When Ocasio-Cortez was elected, there became this fear-mongering that occurred, of feeling uncomfortable [about] a new direction for the U.S. that destabilized traditional figures of power in the Democratic Party. A lot of news reports started positioning Ocasio-Cortez as directly antagonistic, for example, to Nancy Pelosi, threatening to [send] the nation into further chaos. Comparing Ocasio-Cortez to Trump by saying, These are both extremist figures. We need to get back to a moderate center. We need to re-stabilize the nation. These insurgents—they were called [in] a lot of reporting from the New York Times to the Wall Street Journal—need to be stopped.

And the Green New Deal was picked up and lumped into this fear-mongering about a so-called “far left takeover” of the Democratic Party led by young women of color. National polls showed how in just a few short months of this—a lot of national news coverage and also political discourse from Democratic Party members—there is an extreme drop in support for the Green New Deal.

The Inflation Reduction Act, a couple years later, was positioned as being, This is what we need to do. In contrast to the Green New Deal, the Inflation Reduction Act is developed by these older, more moderate, more “reasonable” men like Biden. The Inflation Reduction Act is how to respond to the present moment, the chaos and crisis, in a reasonable way. This is the correct way of responding to climate change. The Green New Deal is not. These different ways of positioning two policy positions was very revealing and showed that there was this real uniting around “othering,” or fear-mongering, about progressive activists and politicians.

I’m certain, given how they’ve covered Trump for the last decade, that a lot of legacy media institutions think of themselves as antagonistic to Trump and MAGA and the far right. They think of themselves in a superior way because they are not that. But you show that they’re actually using a lot of the same tactics and relying on a lot of the same narratives.

Again, this striking statistic of how the Green New Deal was supported by 81 percent of people at the time: There’s this desire for radical change, for comprehensive change, among most Americans. It’s not actually dangerous or unpopular to be imagining politics differently. This is what people want. And by not addressing this, it fuels really authoritarian figures like Trump. If there was a leaning into, instead of fear-mongering about, these progressive visions for change, then perhaps there could have been a stronger coalition to oppose Trump ahead of 2024, instead of breaking these coalitions and pushing people away.

In national news coverage and commentaries that were trying to provide interpretation for unfolding events happening between Trump’s first [and] second election, there was this real fear of mass politics across the board, and there was a lack of distinguishing between different political positions. The “moderate center”—those who consider themselves to be moderates—[are] making these false equivalencies, positioning Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as the same as Trump, for example.

What is dangerous about this is that this “othering” isolated primarily young women of color as the dangerous “other” that needed to be removed from the nation, needed to be removed from politics. That was happening from the moderate center and the right. This led to a really dangerous echoing on the right and the center of positioning the so-called new New Left, which the New York Times referred to young women of color-led progressive politics that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and contingents for climate justice and the Green New Deal represented, as really anti-American, socialist, Red Scare fear-mongering from the moderate center to the far right.

Together what this led to is ultimately the calls for removal from politics of a historically marginalized and formally disenfranchised group of young women, and the further centering of traditionally privileged figures of power—these white older men and women. It’s pretty dangerous that there was this isolation, this call for eliminating a whole group.

These progressive people could have provided important coalition building and pathways for responding to Trump’s politics, pathways for responding and including more people in decision-making, and it would have been popular. It’s just really alarming to see that there was this coalition, almost, that formed between the moderate center and the far right to get the new New Left out of politics.

Power structures successfully preserved.

Yep.

From the “moderate center” to the far right to the Silicon Valley techno-libertarian types, a commonality among these different groups [is] contempt for ordinary people—that 81 percent of people who backed a lot of the tenets of the Green New Deal. I would add, in a lot of cases, capital-“d” Democratic elites do not think very highly of the average person. Can you talk about that idea that, as you put it in the book, “the people are the problem”?

There’s this real sense of unease at the prospect of mass politics—so, essentially, democracy. Tapping into longstanding myths [of] Hobbesian “law of the jungle” chaos: If people are left to their own devices, it would lead to utter chaos. Apocalyptic visions of collapse. There needs to be these elite figures, these visionary sages, to guide the chaotic, brutal masses out of the barbaric present into a bright future.

This myth circulates across different groups of folks who are in positions of material power and have a lot of wealth, and also symbolic power—in these newsrooms reporting, or elected officials who have [a] platform. There’s this real disdain and feeling of needing to control people.

It’s taken to an extreme when the masses, the people, are positioned as unnecessary. This chaos that is predicted with climate apocalypse, for example, and the mass death that’s imagined, is almost welcomed by some figures. As you can see with figures like Elon Musk and Peter Thiel, the techno-libertarian extreme, they almost morbidly celebrate the prospect of there being this apocalypse, this mass death and destruction of the masses, because then it affords them the opportunity to have total control [and] power. There’s no accountability, no need for that pesky thing called “democracy,” because everyone’s gone. It’s just them. They’re able to now build their fiefdoms, their colonies on Mars. They can do what they want.

It moves to a dangerous extreme where there’s constant disdain or assumption that the masses are just mindless, dumb, dangerous people. It can lead to imagining and romanticizing about mass death. That is really scary. It’s a terrifying way of thinking about people.

You point out in the book how that mentality, while not to the same Thiel-Musk extreme, in some of the media coverage does show up [as a divide between] the “doomed others” and the “saved selves.” This idea that an “epic climate migration,” to quote one New York Times headline, is inevitable, and essentially the battle [against climate change] is lost. It seems like a lot of the discussion is not, “How do we prevent this from happening?”, but instead, “How do we assuage our own guilt for having let it happen?”

Can you talk about that fatalism that pervades so much coverage of the climate crisis? I think a lot of the people behind it would think of it as very different from the Thiels and Musks of the world. But it actually shares some of the same worldviews and advances some of those same ideologies.

There’s what I call in the book a Dr. Frankenstein dynamic. In news coverage it is acknowledged that the U.S., for example, has contributed substantially to climate change, has caused some serious problems in world affairs. There’s news reports and also opinion commentaries that admit the U.S. created the monster, like Dr. Frankenstein created a monster.

But then [they say], Now the U.S. is the only one that can solve it. Dr. Frankenstein’s the only one that can capture and contain the monster. This [framing] further asserts the need for these elite, visionary sage figures to be the ones, and claims that they’re the only ones capable of “solving” climate change. Also positioning the U.S. as the main player needed to design a way out, that needs to be followed by everyone. This assumes that there’s the inevitable “saved.” The U.S. largely imagines itself, and figures like Musk and Thiel and elite figures within the U.S. imagine themselves, as inevitably the ones that are going to be saved—not to mention plans to escape to Mars or apocalypse bunkers.

[They] imagine themselves as being the ones who of course will be saved and in control of who to bring up into the so-called “life world” with them. They imagine everyone else being at risk of dying or inevitably doomed and damned, and they’re in the position to choose who to save. A lot of the times, in the reporting that I saw, there was this assumption that those who will inevitably be doomed and dead are poor people of color living in the Global South. There were a lot of images showing this mass destruction after climate-induced storms in the Global South, entrenching this idea that the Global South is already lost. They’re gone. And the U.S. and the Global North are empowered to choose who to save or who not to.

That’s not a way of representing reality. That’s [not] going to lead to bringing lots of people together from a lot of different places to figure out how to respond to climate change in a democratic way. If it’s already assumed that whole groups of people are going to be dead and gone, then that’s not leading to their inclusion in international negotiations in a meaningful way. It’s not leading to thinking about how to integrate and include lots of people into different societies. And it’s making it seem like those who need saving are being given a favor by being brought up into a Global North country.

This fear-mongering about mass migrations—bringing folks from these chaotic, apocalyptic scenarios up into the presumed saved, stable, Global North “life world”—leads to a lot of scary anti-immigrant sentiments when thinking about climate change.

What [are] some of the consequences for more hopeful, democratic, and participatory movements, like the climate justice movement, when these are the only stories that are allowed to be told?

I think what is really important about climate justice narratives and movements are that they disrupt this idea that there are just a small number of elite figures that know all and can save all. The climate justice movement says [that] lived experiences, different knowledges, are important to figure out what are the impacts of climate change and what can be done about it. It shows that people can come together, so it disrupts this narrative of the masses being chaotic and dangerous and dumb. It shows that mass movements actually can provide really important ways of responding. People want to work together. They want community.

These climate justice spaces and movements are countering and poking holes in these myths that apocalyptic authoritarians are trying to tell in order to claim their authority and their power.

I wanted to ask you about some of the antidotes to apocalyptic authoritarianism and this sense of fatalism about inevitable collapse. You talk about “radical hope” and “robustly democratic decision-making processes.” Can you explain what those are?

Radical hope is countering the assumption that there’s going to inevitably be an apocalypse. That’s important because these apocalypse narratives can be taken up to claim that there’s those who are saved and those who are not, and those who are saved can choose who to bring with them. So it closes off these more democratic imaginings for how to respond to present-day issues. Radical hope, then, is disrupting that bleak future, that morbid future, that future that is fundamentally anti-democratic and authoritarian.

Robustly democratic decision-making processes would not be these top-down, elite-driven claims of absolute authority. Robustly democratic ways of imagining how to respond would include being comfortable with the fact that there isn’t one silver bullet “solution” to climate change. It isn’t just “one plus one equals two.” There’s many different ways of responding. It shows that there shouldn’t just be one superpower that decides how to respond and how every other country should respond. There should be a lot of different ways of imagining what can be done.

This centering of radical hope and robustly democratic decision-making points towards these alternate pathways. Being comfortable with not knowing, too, [and] not having control. Being open to different ways of living, different ways of building societies.

How would you see that manifesting in a “reimagined climate journalism”?

First of all, there needs to be a rupturing of this fear of the masses that is part of a lot of the fundamental groundwork of reporting. Traditional journalists, in a lot of ways, imaging themselves as sort of “civilizing,” or providing stability, providing this information that needs to be read and consumed by the masses in order to have a stable, civilized society—that identity needs to be changed.

Instead, thinking about members of different groups as more than just readers, but as participants, as part of the news-making process is a first step, I think, for reimagining journalism. This movement away from imagining people as masses or faceless consumers or readers, but multi-dimensional, dynamic subjects who are different and smart and capable and want change and are willing to put the work in to do that.

A part of that, then, is disrupting these binaries, these simple narratives that position anyone who is advocating for change as “extremists.” Being comfortable, again, with not having control, not knowing the direction that the future holds, and being okay with the possibility of robust democracy. The only way to respond to climate change, in a really fundamental way, is having a robustly democratic political-economic system, and not having these gluts of power that have led to climate change to begin with.