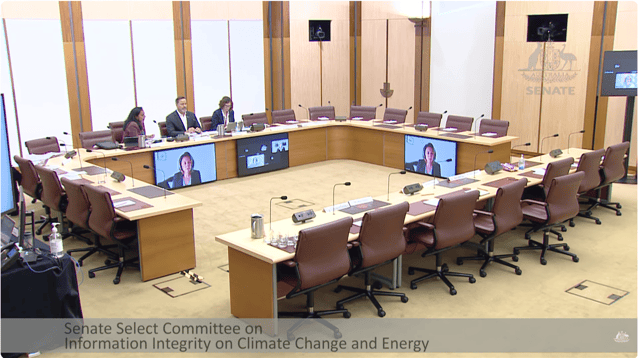

Photo: Uncle Pabai Pabai and Uncle Paul Kabai on their way into court with their lawyers. Photo by Bella Laifoo, courtesy Granta Fund.

They were two decisions, from two separate courts issued both a week and a world apart. One, a class action lawsuit filed in 2021 by a First Nations community in the Torres Strait, alleged the Australian government had failed to meaningfully address climate change. The other, an advisory opinion from the highest court in the world that began as a campaign in 2019 by law students from the University of South Pacific, sought to get the International Court of Justice to advise on the obligations of governments to address climate change under international law – and succeeded in giving the Paris Climate Agreement teeth.

Many had hoped the first, referred to as Pabai Pabai, would make Australian legal history. It was brought by two lead applicants, Uncle Pabai Pabai and Uncle Paul Kabai, on behalf of an Indigenous people who live in Zenadth Kes – the Indigenous name for the islands of the Torres Strait and the people who live there. These islands number about 200 and lie between Australia and its northern neighbour, Papua New Guinea, though only about a dozen are inhabited. The area has been on the frontline of both fossil fuel extraction and the impacts of climate change. Over the last few decades rising sea levels, storm surges and extreme weather events exacerbated by climate change have been making inhabited areas unliveable. Seawater has invaded food producing areas, vegetation has started to die and sites of cultural significance are slowly being eroded and inundated. Residents of the islands report king tides sweeping through gravesites, forcing them to dive to rescue the remains of their ancestors.

Where climate cases have taken aim at fossil fuel companies and their industry associations, Pabai Pabai took aim directly at the Australian government. The case, based in negligence, claimed that the Australian government owed residents of the Torres Strait a duty of care and had breached this duty by failing to take meaningful action to address climate change. It was not the first to make this case – a group of young people had tried to make the same argument in 2020 but had their initial success overturned on appeal in a case that has become known as the Sharma decision. This time around, it was thought the Torres Strait Islanders had better odds. A treaty Australia had signed when it took possession of the Torres Strait Islands made it easier to establish a duty of care, and the scientific evidence on the reality of climate change was overwhelming.

Justice Wigney, a single judge of the federal court, shot down the application. Wigney was explicit in his ruling that climate change represented “an existential threat to the whole of humanity”, was already having an effect on the Torres Strait and the way of life for those who lived there, and that the Australian government had paid “scant regard” to the science when setting its emissions reduction targets. It was impossible for him not to. In evidence, public servant Kelly Pearce had told the court during hearings in Melbourne about her time leading a taskforce to advise the Australian government on options for emissions reduction targets in anticipation of negotiations in Paris that ultimately led to the Paris Climate Agreement. Pearce told the court that the taskforce did not consider the impacts of climate change on the Torres Strait, or any other community, beyond broadly acknowledging there would be some form of impact from extreme weather events.

Despite this very real recognition of harm and negligent activity by the Australian government, Wigney ruled that his hands were bound by precedent. Australian courts have so far maintained a policy of treating climate change as a political issue best resolved by democratically elected parliaments, not courts – even as Wigney appeared to hint that it would be up to a higher court to change this policy.

“That will remain the case unless and until the law in Australia changes, either by the incremental development or expansion of the common law by appellate courts or by the enactment of legislation,” Wigney said.

“The only real avenue available to those in the position of the applicants and other Torres Strait Islanders, involves public advocacy and protest and ultimately recourse via the ballot box.”

The Torres Strait Islanders won on the facts but lost on the law – the inverse of another recent decision in German courts. There, a Peruvian farmer on the other side of the world sued Germany energy giant RWE in nuisance for climate harms resulting from their historical emissions. In that matter, the court ruled that German companies were liable in German law for their historical emissions, but dismissed the matter on the basis that the harms alleged had yet to be suffered – even if they are inevitable. None of these technical distinctions mattered to the people of the Torres Strait. Speaking outside of court, they expressed their shock at how a court could recognize they are losing their home and culture and yet do nothing.

“My heart is broken for my family and my community. Love has driven us on this journey for the last five years, love for our families and communities. That love will keep driving us,” Uncle Pabai Pabai said.

Uncle Paul Kabai said: “I thought that the decision would be in our favour, and I’m in shock. This pain isn’t just for me, it’s for all people Indigenous and non-Indigenous who have been affected by climate change. What do any of us say to our families now?”

In its own statement released afterward, the Australian government said it was “carefully considering the judgement” and that it was working to “turn around a decade of denial and delay on climate, embedding serious climate targets in law and making the changes necessary to achieve them.”

“Australia is now producing record renewable electricity, and energy emissions are lower than when we took office. We’re on track to achieve our ambitious but achievable targets of 43 per cent emissions reduction by 2030,” the statement said.

The community’s legal team is expected to appeal the decision.

Dr Liz Hicks, a lecturer at the Melbourne Law School, says the decision in Pabai Pabai is significant for the way it exposes a crisis of legitimacy in the Australian courts. In trying not to interfere with democratic processes on climate change, courts have increasingly refused to act on climate change at a time when political processes have been failing to respond to the crisis, forcing vulnerable people to seek help in the courts.

“I think what we’re doing here or what courts are struggling with here is having to trade off two crises of legitimacy,” Dr Hicks says. “The short term one is this risk or idea that the court may develop the law in a way that goes into that political space. But there is the longer-term problem of a crisis of legitimacy if the law has nothing to say about accountability for the major source of harm to people’s lives in society, that the law also recognizes is occurring.”

The contrast between the decisions of Australian courts and the ICJ advisory opinion by the world’s highest court is stark. As the residents of the Torres Strait have been battered by climate change, so have Pacific Nations. In one now famous video, Tuvalu’s former foreign minister Simon Kofe gave a speech via video link to COP26 in Glasgow while standing knee-deep in seawater to illustrate the threat posed by rising sea levels. In November 2023, signed a migration deal that would gradually allow its citizens to relocate to the Australian mainland to escape rising oceans, while keeping their citizenship. There are similar stories across the Pacific, which has prompted civil society groups and governments to make climate accountability and climate action a central issue even as their nearest neighbours have prioritised fossil fuel extraction over their safety. New Zealand, for instance, recently confirmed it was quietly quitting its climate agreements to reboot gas exploration, and Australia today vies with Qatar and the US for top position as the world’s largest LNG exporter, while the Port of Newcastle remains the world’s largest coal export port. At present the country has given approvals to several massive new gas projects, including critical approvals needed for Woodside’s $16.5bn Scarborough gas field off the northern Western Australian coast and Santos’ $5.6bn Barossa gas development off the coast of the Northern Territory.

These dynamics were clear as the ICJ began public hearings at The Hague. What began as a campaign by the Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change for the ICJ to rule once and for all on the legal right to a healthy environment, as well as governments’ responsibility to act on climate change, was given momentum when it was endorsed by several pacific governments, including Fiji, Tuvalu and Kiribati, and represented by Vanuatu. Together they sought to have the ICJ clarify the obligations of states to tackle climate change – a push endorsed with a unanimous vote by the UN General Assembly.

Vanuatu’s climate minister, Ralph Regenvanu, opened hearings at the ICJ where he told the court “I choose my words carefully when I say that this may well be the most consequential case in the history of humanity”. He would ultimately be proven right. Australia, for its part, had supported the push for the ICJ to hear the matter and was among the first countries to make submissions where it directly contradicted the arguments put forward by Vanuatu and other Pacific countries. Alongside major polluters including the US and the UK, Australia argued the Paris Agreement was the world’s mechanism for dealing with climate change and there was no obligation in international law to go beyond what it required. When Judge Yuji Iwasawa delivered the ICJ’s advisory opinion on Thursday, the unanimous decision of the court sided with the Pacific when it explicitly rejected the idea that minimum compliance with the Paris Climate Agreement was enough.

“Failure of the state to take appropriate action to protect the climate system from greenhouse gas emissions including through fossil fuel production, fossil fuel consumption, the granting of fossil fuel exploration licenses, or the provision of fossil fuel subsidies – may constitute an internationally wrongful act which is attributable to that state,” he said.

In its opinion, the ICJ outlined how governments—including those that are not signatories to the Paris Climate Agreement—have an obligation to address climate change that includes properly regulating private actors, that inaction amounts to a human rights violation, and that governments that fail to act face liability under international law for these breaches.

Outside, Regenvanu spoke at a press conference on the court steps where he said the decision was a “very important course correction at this time” that found “climate science is at the heart of climate law and the compass for climate justice”. He also flagged potential future litigation against polluting countries like Australia.

“Today’s ruling is a landmark moment, and it’s confirmed what we vulnerable nations have been saying and have known for so long: that states do have legal obligations to act on climate change,” he said. “And these obligations are grounded in international law, they’re grounded in human rights law and they’re grounded in the duty to protect the environment, which we heard the court refer to so much.”

“And these aren’t aspirational ideas as someone would have it. The advisory opinion has clarified the legal consequences for states which fail to discharge these obligations.”

It did not take long for the ramifications for countries like Australia to be recognised. Bill Hare, a climate scientist and CEO of Climate Analytics, said the ruling placed responsibility on governments to “regulate private activity within their jurisdictions and they have a responsibility to all other states for the consequences of actions taken, and this together means that countries have an obligation to limit, reduce and ultimately eliminate fossil fuel production.”

“The ICJ points to potential for serious legal consequences under customary international law if countries do not put forward targets aligned to 1.5°C. Importantly, these obligations also apply to countries whether or not they are Parties to the Paris Agreement,” he said.

An advisory opinion of the ICJ may not be binding in Australian law, but Retta Berryman, senior specialist lawyer at Environmental Justice Australia said it will be influential by setting “a new legal standard for climate justice” and will likely be factored into upcoming negotiations for COP30 in Brazil. Isabelle Reineke, Executive director of the Grata Fund and the litigation funder in Pabai Pabai, said the ICJ opinion “officially marks the end of an era of states ducking and weaving legal responsibility for climate harm” and that it “seriously calls into question the legality of Australia’s current and past policy setting under international law, including its past and ongoing approval of fossil fuel projects.”

“It makes crystal clear that so long as the Australian Government’s efforts to protect the world’s climate system falls short of stabilising global heating at 1.5 degrees, it could be liable to litigation from other countries,” she said.

In its own statement, the Australian government said it “will now carefully consider the court’s opinion”.

Australia is no stranger to litigation over its environmental and climate harms. In 1993, Nauru won $135m in an out of court settlement with Australia for environmental pollution caused by phosphate mining on the island. More recently, the UN Human Rights Committee found in 2019 that Australia had failed to act on climate change following a separate complaint by Torres Strait Islanders. As the decision was non-binding, however, it was ignored. With the ICJ opinion, Australia’s fossil fuel production looks more like a liability than an asset – a ruling that Dr Liz Hicks says shows how recent Australian court decisions such as Pabai Pabai are out of step with the rest of the world.

“The approach of the Australian courts so far [on climate] looks increasingly awkward and at odds with the path many courts elsewhere in the world are taking on climate accountability and how law organises climate politics,” she says. “We look like we’re saying that the particular circumstances of our law and our tradition mean we have to follow a path different from anyone else – even if it produces absurd consequences in the law and the law’s capacity to regulate harm across society.”

“The law has always adapted to the problems that are put in front of it. If it doesn’t, then it breaks. But it’s always taken a critical mass of demands from across society before that happens. The pressure for change is building.”