Kusmunda open cast mine owned by South Eastern Coalfields Limited (SECL), a subsidiary of Coal India Limited. Photo credit: Rishika Pardikar

At the confluence of three open cast coal mines in central India—Gevra, Kusmunda and Dipka—the landscape seems like a whole other planet. From above, the mined land looks like terrace farming. Below, the ground is black and workers move around in huge trucks amid coal dust all day.

Gevra and Kusmunda are two of the world’s five largest coal mines and each produce about 50 million tonnes of coal every year. Overall, India produces about a billion tonnes of coal annually, second only to China.

Coal meets about 55% of India’s energy needs and is important for energy security. Unlike the U.S. and some European countries, India does not have adequate oil and gas reserves to provide baseload power. And imported oil and gas are expensive. So, the country relies on coal to meet the growing energy demands of 1.4 billion people even while renewable energy continues to grow.

Many coal districts also have a significant Adivasi—Hindi for “first peoples”—population. Given that a lot of forested lands that are now coal mines were once home to these communities, it’s just as important that an energy transition recognizes historical land and forest rights of these communities as it is to do right by coal workers.

Then there’s the Adani group, with coal mining operations across India and also other countries like Australia and Indonesia. Its chairman and founder, Gautam Adani, is a close friend of prime minister Narendra Modi and the second wealthiest man in Asia. Over time, the group has grown as the largest private developer of coal not just in India but also the world. And with this growth, came opacity in operations, crony capitalist favors and police action against protesting Adivasi communities.

In this context, the challenges of planning a socially and economically just transition away from coal are clear. Drilled visited the country’s coal belt to fully understand that task.

At present, while discussions about a ‘just transition’ are happening at the national and academic level, there is nothing tangible about an energy transition on the ground across coal-heavy districts like Korba and Sarguja in Chhattisgarh where industry talk is still fixated on “MTPA” (million tonnes per annum) to quantify the benefits of ever-increasing coal production.

‘Coal is everywhere. Today they will mine here, tomorrow there’

Gevra, Kusmunda and Dipka mines are owned by South Eastern Coalfields Limited (SECL), a subsidiary of the state-owned enterprise Coal India Limited. All three mines are located in the district of Korba in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh.

Overall, Chhattisgarh contributes about 20% to India’s annual coal production. Other states in the coal belt are spread across central and eastern India in Jharkhand, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal.

The mining sector across minerals like iron ore, coal, limestone and bauxite is a major contributor to Chhattisgarh’s economy where coal alone contributes 13% to the economy. Coal also supports hundreds of thousands in direct employment at mines and thermal power plants and indirect employment like transportation, maintenance and other associated activities in the state. Heavy industries like steel and cement and brick kilns are also big consumers of coal in the state.

Gevra open cast mine also owned by SECL. Photo credit: Rishika Pardikar

While travelling from one coal district to another in February 2025, we saw posters for local body elections underway in the state of Chhattisgarh. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the party of the prime minister, swept these polls.

Manifestos of contesting candidates included promises of ensuring appropriate compensation for lands taken over by coal mining and also employment.

“Coal is everywhere but we get nothing from it. Only 20% [of the local population] get permanent employment. And there’s no land for rehabilitation [post displacement for coal mining] because coal is everywhere. Today they will mine here, tomorrow there,” said Manjeet Yadav, a resident of Bhathora village.

People from Bhathora have previously protested and even stopped coal mining activities by SECL at Gevra mine seeking adequate compensation for their land and employment.

“Land acquisition is the toughest task,” Partha Mukherjee, general manager (mining) for SECL’s Kusmunda project told Drilled.

The first step for any newly proposed coal mine is an announcement by the Government of India that it intends to acquire the land under the Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition and Development) Act. “From the time of declaration under the Act to actual possession of the land is a very long process. Resettlement and rehabilitation and providing employment is very challenging,” Mukherjee adds.

Private mines to nationalization and back again

Industrial coal mining in India traces its roots to British colonialists who needed it to fuel steam-powered ships and railways. After independence in 1947, coal mines moved to private hands. Then, in the early 1970s, the coal sector was nationalized.

From then to now, a majority of coal in India has been produced by the state-owned enterprise Coal India Limited. Today, Coal India Limited produces about 80% of the country’s coal. However, private coal mining operations have slowly expanded since economic liberalization in the 1990s, spurred by loans from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund and associated reforms.

The Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act was amended to allow private businesses to mine coal for use in their own power plants or cement or iron and steel production. The private sector could not sell the coal it mined. But captive use was allowed and in part necessitated by the inability of Coal India Limited to meet coal demand across the country, especially by power plants. Over the years, the government also subcontracted activities like removing overburden (layers of soil and rock that lie above the coal seam) and extracting and transporting coal to private businesses.

In 2020, the Modi government opened the coal sector as a whole to commercial coal mining. The move was, at least in part, aimed at undoing a Supreme Court ruling that shook the entire Indian coal sector just a few years earlier. In 2014, the Supreme Court declared the allocation of nearly 200 coal blocks in the 1990s and early 2000s as illegal and arbitrary, effectively reneging on the previous 20 years of coal block allocations to the private sector. Modi’s move to open the sector to commercial enterprise was a way to address private sector concerns over the ruling.

“Essentially, the government said look, the Supreme Court may have made this decision but we still think private coal mining is a good thing,” Rohit Chandra, a professor at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi explained. “So, we will find a way to auction coal blocks without restricting its end use [like the Coal (Nationalisation) Act previously prescribed]. And private companies can mine and sell the coal in the market to end users.”

The Modi government also introduced the ‘mine developer and operator’ (MDO) model for the coal sector. Under this model, state-owned enterprises like Coal India Limited continue to own the coal mines while the development of the mine, including land acquisition processes and actually running the mining operations, are handed over to private entities. The aim behind the MDO model was "streamlining operations, enhancing productivity and reducing mining costs".

Questions remain, however, about the extent of actual productivity and efficiency in private mining operations given that competitiveness is attributable in large parts to labor arbitrage. Private businesses engage workers through informal arrangements where pay rates can be less than half of those provided by Coal India Limited. Private businesses also do not have other labor responsibilities like overtime wages and pensions. On the other hand, employees of Coal India Limited are unionized and have far greater bargaining power than those in the private coal mining sector.

“There are issues with low wages and non-provision of medical, education and housing facilities [with the MDO model]. Today, Coal India [Limited] provides all of this,” said R C Mishra, general secretary for Chhattisgarh of the Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC). INTUC has a membership of about 30 million workers across the country.

A review paper published in February 2025 in the journal WIREs Climate Change, titled ‘India’s Coal Conundrum: Decarbonisation Amidst a Developmental Legacy’ throws light on Coal India Limited’s approach to development, or developmentalism. As has been the case in many other coal-producing countries, including the U.S. and Australia, coal “company towns” have been central to Coal India Limited’s approach.

“For many coal-adjacent towns like Dhanbad, Asansol, Chandrapur, Korba and Bokaro, coal companies played a material role in developing some basic public goods and institutions in the areas; until the early 2000s the best schools, dispensaries and hospitals in these areas were often run by coal companies,” the paper reads. “Even today, over 1 million people live in [Coal India Limited] housing, and a similar number of people benefit from [Coal India Limited] providing water to villages for both residential use and irrigation. Given the absence of state capacity in much of India's hinterlands, [Coal India Limited]'s developmental role becomes an important feature of regional polycentricity as multiple actors take partial responsibility for local development.”

However, the paper also notes that such benefits were largely “enclave developmentalism” and “highly politically mediated” benefits that rarely reached poorer sections of the society like landless laborers and marginalized communities like the Adivasis.

On the MDO model, Partha Mukherjeee, the general manager (mining) of Kusmunda too had questions. “Private entities have lesser cost of production with contracted labor. For us [SECL], salaries of permanent employees and daily wages are a very high cost. How can we compete with them?” he asked. He added that the MDO model for coal operation is still in its early stages and how it works out in the long term remains to be seen.

At present, the Adani group is the largest MDO in India. Other private businesses that have bagged MDO deals include Thriveni Sainik Mining Private Limited, which the state-owned power generation company National Thermal Power Corporation relies upon.

Journalistic investigations have revealed how the Modi government worked in secret to favor Adani in coal deals.

In another case where a coal mine was allotted to the state electricity generation company of the western Indian state of Rajasthan, the MDO model again favored Adani at the cost of the state exchequer. Such allocations also raise serious questions about whether coal - increasingly in the hands of private players and under the pressures of crony capitalism - can offer energy security for the people of the country.

“The whole point of allocating coal blocks to state-owned power generation companies is that it reduces the cost of coal and the cost of electricity. And there is assured supply. But what we see today is that the state is buying its own coal at a higher price from Adani,” said Sudiep Shrivastava, a lawyer based in Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh who has challenged the MDO model in the Supreme Court of India.

D K Soni, the petitioner in the MDO case before the Supreme Court which Shrivastava is arguing, said the MDO model has allowed Adani to mark good quality coal as reject quality and sell it privately at a high cost, while selling low quality coal to the state government of Rajasthan. Soni is a lawyer and a Right to Information (RTI) activist based in Ambikapur, Chhattisgarh. The RTI Act is India’s equivalent of the Freedom of Information Act.

“All political parties need money and they favor big businesses like Adani. But the BJP has surrendered fully to Adani,” Soni said. BJP, the party of prime minister Narendra Modi, has been in power nationally since 2014, and is in power in the state of Chhattisgarh as well.

Further, Soni added that India is not planning its coal mining operations properly. “We need to first use areas which are already being mined [for coal] before opening new forests,” he said. “Some of the forests in Chhattisgarh are centuries old. We cannot plant such forests today. Bears used to live very close to our cities but now we don’t see them. These forests also had a lot of medicinal plants which were used by villagers.”

Adani operations in sacred forests

“This is PEKB. And this is Parsa,” said Muneshwar Porte, stretching one arm and then the other, in two different directions. Both pointed to coal mines operated by the Adani group in Hasdeo Arand forests, in the district of Sarguja in Chhattisgarh. The region is home to the Gond community, an Adivasi population.

Porte too belongs to the Gond community. They are animistic and tree-worship is a dominant part of their spiritual beliefs. The two coal mines were built on previously forested lands that the Gond community considers sacred.

PEKB stands for ‘Parsa East and Kente Basan,’ a coal block spread over 27 square kilometers where operations began in 2013. And Parsa, which is still under development, is 12.5 square kilometers. PEKB has the capacity to produce 15 million tonnes of coal per year and Parsa about 5 million tonnes.

Muneshwar Porte at the edge of PEKB coal mine which used to be a forest. Photo credit: Rishika Pardikar

On 30th March, prime minister Narendra Modi visited the state of Chhattisgarh. He laid the foundation stone for inaugurating new thermal power plants and spoke from a podium about how his government has provided houses to Chhattisgarh’s poor, and to Adivasi populations in particular.

Within two days of Modi’s visit, tree-felling for the second phase of the PEKB mining project began. The Gond community has consistently opposed such mining operations on their lands because they consider the trees sacred and forest produce provides them nutrition and livelihoods.

Gond women humming while working in rice fields. The same women faced police batons and firing when protesting against the expansion of Adani’s Parsa coal mine. Photo credit: Rishika Pardikar.

Sunita Porte, another member of the Gond community recollects how, when they were protesting against the felling of trees for Parsa coal mine in October 2024, Chhattisgarh police opened fire on them and beat them with batons without regard to the presence of children. “Some of us had taken our children along. But the police did not care who they were hitting,” she said. Several people were seriously injured in this incident.

Additionally, the police lodged legal complaints, locally called First Information Report (FIR), against ten community members, including Muneshwar Porte and Sunita Porte, accusing them of endangering the lives of police forces. Drilled has seen copies of the FIR. It states that 70-80 villagers, armed with sticks and slingshots, had gathered in protest of tree-felling and aimed to “obstruct government work with intention to kill.”

High-handedness by both government authorities and coal companies is not an uncommon occurrence in these areas. The community tells us about past instances where local journalists were harassed and data on their phones were deleted by “dalaals” (brokers or middlemen in Hindi) contracted by the Adani group. These agents offer a variety of services to the companies that hire them, including negotiations with local communities for land acquisition.

There are ongoing resistance movements against Adani’s coal operations in other coal belt states like Jharkhand too.

A renewed push for underground coal mining

Meanwhile, the Indian coal ministry is planning to boost underground coal mining with an aim to increase the country’s underground coal production capacity threefold to 100 million tonnes by 2030. But the move raises concerns about worker safety.

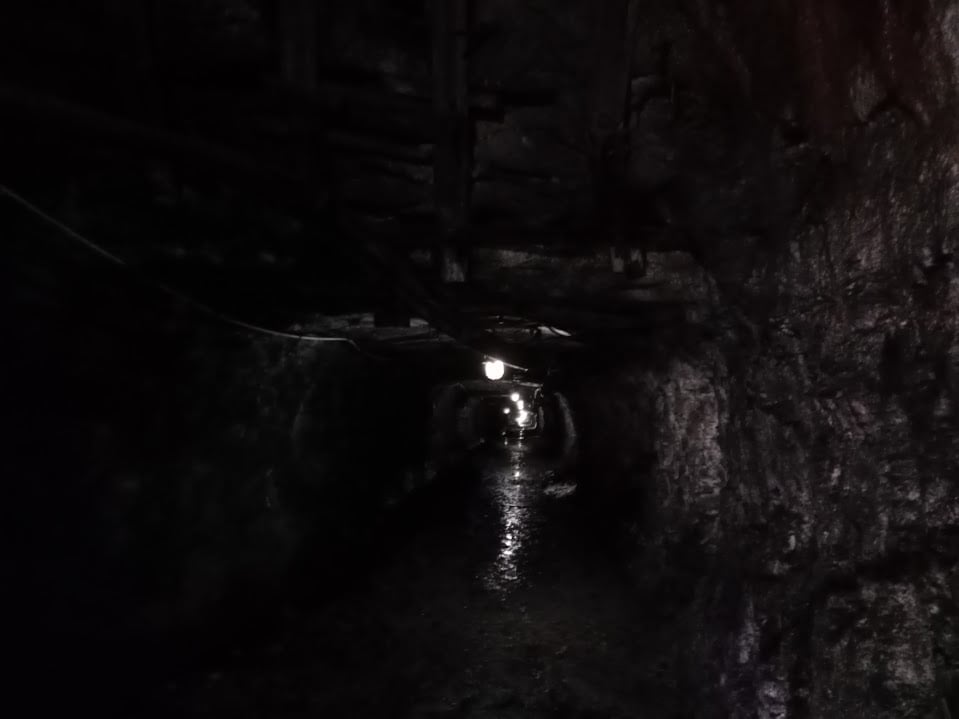

A 300-feet deep underground coal mine in Bishrampur, Chhattisgarh. Photo credit: Rishika Pardikar

On 20th February, two days before our planned visit to the town of Chirmiri in Chhattisgarh we heard about the death of a worker in an underground mine in the same area. We met local journalists who told us no one knows how many people actually die in underground coal mines because the management hides it.

Deaths in underground mines invite investigations by the Directorate General Of Mines Safety which is a regulatory agency under the Indian labor ministry. The journalists say management-level employees of underground coal mines never let word about deaths leak out to the larger public to avoid scrutiny and closure of the mine.

Accidents are less common in underground mines that do not use blasting technology and instead use a machine called a ‘continuous miner’ to excavate. On the condition of anonymity, a medical staffer at a hospital run by SECL told us that roof collapse is the major reason for deaths and serious injuries and that blasting technologies often lead to such accidents.

A piece of coal from the coal seam in an underground coal mine. Photo credit: Rishika Pardikar.

Worker death and injury is not a unique feature of underground mines; workers in open cast mines are prone to injuries and deaths in other situations like truck accidents. Fatal accidents are not uncommon along coal transportation routes outside the coal mines either. We came across a small board displayed by the roadside that highlights nine cases of accident-caused deaths in the last three years within that particular stretch of 500 meters, and advised caution.

These risks to health and life are in addition to those posed by exposure to high levels of air pollution.

A 2014 study published in the journal Atmospheric Pollution Research found high concentrations of particulate pollution and also sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and heavy metals in an assessment of air quality in a coal field in Jharkhand. More recently, a 2024 study by the National Foundation for India (NFI) showed widespread respiratory and skin diseases across six districts in India’s coal belt where coal mining is a major occupation. NFI is a non-profit organization that works on a host of social justice issues across India.

Coal dust in Kusmunda coal mine operated by SECL. Photo credit: Rishika Pardikar.

An energy transition away from coal could mean a safer and healthier livelihood for such workers. But those benefits come alongside serious economic risks that need to be addressed. Over 13 million people are dependent on coal in India today across activities like mining, transport, power generation and sectors like iron, steel and brick-making. Most of these workers are also engaged informally and, given so, the energy transition presents an added layer of precarity for many of them.

On scale and skills, the clean energy sector cannot absorb all coal workers. Additionally, there are regional disparities. Coal, and therefore coal jobs, are concentrated in central and eastern India while solar and wind power, including manufacturing capacity, is concentrated in western and southern India.

The review paper referenced earlier makes a prescient observation: “There is no pareto optimal coal transition; there will inevitably be millions of losers from the decline of the coal industry, and the ideal goal is to foster a parallel developmentalism which can at least partially compensate some losers and provide enough political cover so that the political and bureaucratic classes see this as a desirable pathway. So far much of this basic confidence-building and convincing stakeholders is yet to be done.”