Particularly since the 2018 round of IPCC reports there's been an uptick in climate activism and now the IPCC itself has noticed. "This is the first time that a chapter specifically identified this subject as important on its own and it got allocated a section," says Dana Fisher, PhD, who researches activism and contributed some of her expertise on the subject to the report. The report also mentions a different form of activism—litigation—and its role in helping to drive climate policy for the first time. References to both show up in the Technical Summary, and Chapters 1, 5, 13, and 14. Today we're going to look at the IPCC's take on activism, the organization's somewhat unexpected role as a catalyst for protest in recent years, and what the most recent example of that (the global Scientists Rebellion protests following the release of this mitigation report) might tell us.

For Fisher, being asked to write something on activism for the report prompted some new research as well. "I got asked to write this new section on civic participation in Chapter 13 [the policy chapter] of the IPCC report. And so basically, I was asked to do this big review of all the different ways folks get involved," she says. "And that request to contribute to the IPCC came right when Greta was getting attention here in the United States. And then I also got asked to write this thing on Fridays for Future for Nature Climate. And so I had been doing all this stuff with the Resistance and had been studying climate activism since the 1990s, but this was the beginning of starting to think about youth climate activism in particular."

She wanted to include mention of these new activists in her write-up for the IPCC report, but there was one problem. "They were like, 'Well, this is good, but we need to measure. What is the effect on carbon and climate change? And there's very little research on that."

It's just the sort of question Fisher has spent her whole career trying to answer. "This has been my argument on activism in general: we need more data about who's participating, what are they participating in and why are they participating? So then we know the effects of what they're doing," she says.

Because of her ongoing work studying activism of all kinds, Fisher already had some pretty robust data sets to draw from. She had already looked at the various motivations for people showing up to protests during the Trump Administration (like the Women's March, for example). At most of those protests, Fisher found that people were motivated by different things. But when she looked at the data for climate protests, she saw something else entirely. "In contrast to the inconsistency across all the women's marches, there were patterns—really clear patterns—starting at the People's Climate March in 2017 and then going into the climate strikes, which were very, very different people," she says. "So there are different folks, but they have the same patterns of motivation."

Equality, for example, was a persistent motivator for climate protestors, which Fisher says is important because "we always talk in the social movements world about what can they do to expand the tent and bring in more folks." Broadening the climate movement to a climate justice movement did that.

Fisher made some real progress tracing the effects of climate activism, and that work plus her review of previously existing research turned into a 10-page draft of her section for the IPCC report that was then whittled down to a few paragraphs. The bit on youth climate protests in particular was ultimately two lines: "Climate strikes and other more confrontational forms of climate activism have become increasingly common. Very few studies look specifically at the effect of these tactics on actual climate-related outcomes and more research is needed to understand the climate effects of citizen engagement and activism."

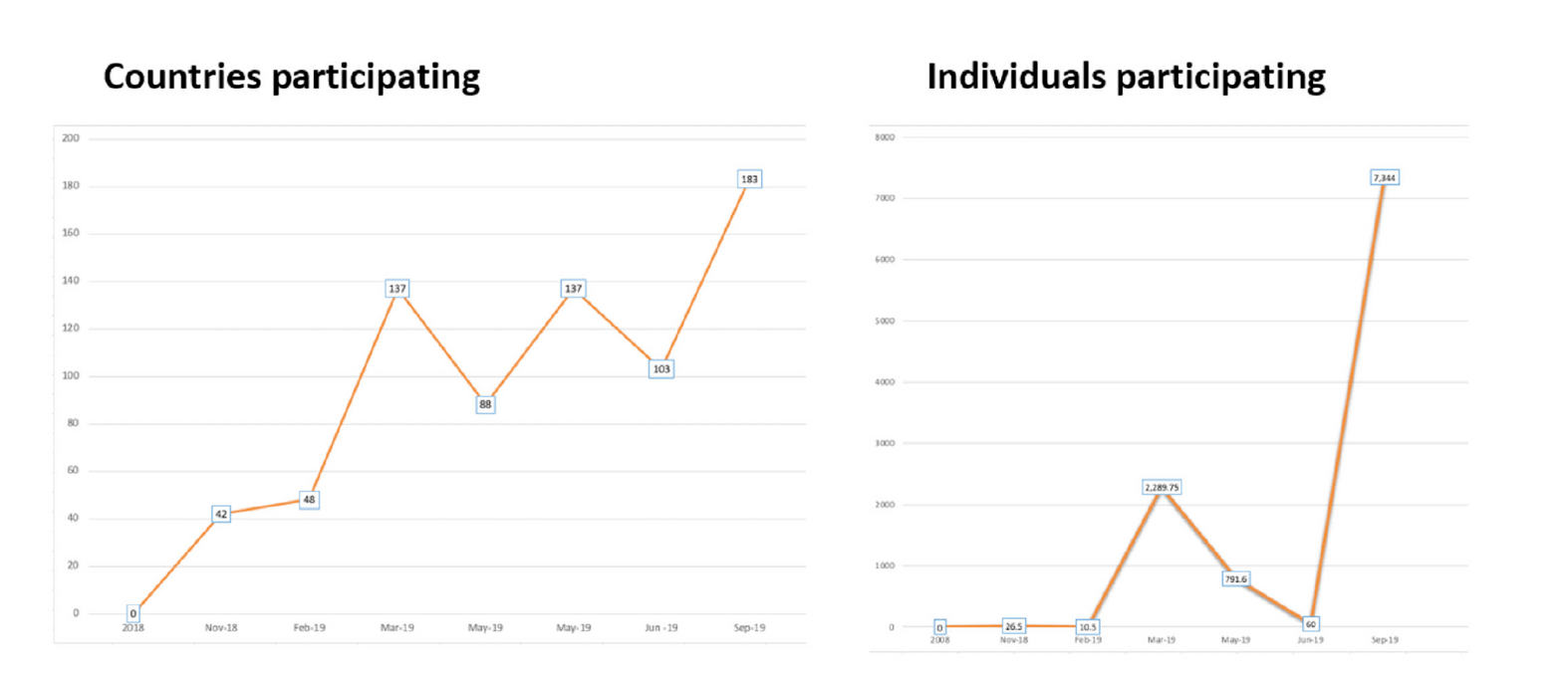

But the original draft became an article for the journal Wires Climate Change: "Climate activism and its effects," which includes this really striking graph from Fridays for Future showing the increase in participation in climate strikes just from 2018 to 2019:

Here's hoping that both the impact and the research assessing that impact are an even bigger part of the next IPCC report. A potential problem? Those "vested interests" we finally heard about officially in this report, some of them quite involved in the IPCC itself. "Seems problematic that Saudi Arabia gets to decide whether or not my statement about climate activism and the role that it plays in foreign policy makes it into the Summary for Policymakers," Fisher says.

One thing Fisher points to around the effect of youth climate activism is the role that young climate activists played in the 2020 election in the U.S. "Young people have been increasingly engaged and motivated by climate," she tweeted this week. "The youth vote played a huge role in Election 2020."

The political impact of climate activism shows up in the IPCC report as well, which notes "Grass-root movements build political pressure for accelerating climate change mitigation, as does increasing climate litigation."

The impact of Indigenous climate activism is also well documented (personally I would point to the fossil fuel industry's coordinated effort to criminalize protest in the wake of Standing Rock as a key indicator here), and noted in the IPCC report: "Indigenous resurgence (activism fuelled by ongoing colonial social / environmental injustices, land claims, and deep spiritual/cultural commitment to environmental protection) not only strengthens climate leadership in many countries, but also changes broad social norms by raising knowledge of Indigenous governance systems which supported sustainable lifeways over thousands of years."

Meanwhile, the IPCC report itself continues to be a catalyst for protest. From the report's release day, on April 4, til April 9, 2022 Scientist Rebellion called for the largest global scientific and academic strike in history, demanding "immediate and radical action in the face of the Climate Emergency." Announcing "1.5 is dead. We need a climate revolution," the group leaked an earlier draft of the IPCC report (a thing that really seems to terrify the IPCC!) and called for scientists and climate researchers to take to the streets. On April 6th, over 1,000 Scientist Rebellion activists in more than 25 countries did just that, many chaining themselves to government offices or corporate headquarters and risking arrest. In Los Angeles, four activists chained themselves to the doors of JP Morgan Chase Bank in peaceful protest and were met with a swarm of police in riot gear who arrested them. Climate scientist Peter Kalmus was one of the four and he was arrested. He says the group wasn't expecting that level of police turnout at all. Kalmus later criticized the media for failing to cover both the IPCC report and the Scientist Rebellion action. While outlets that routinely cover climate news—Inside Climate News, Scientific American, Smithsonian—covered it, as did a few local outlets (LAist, for example), few mainstream national or international outlets did (Al Jazeera and The Independent were notable exceptions), despite the fact that it was, as promised, the largest civil disobedience campaign by scientists in history.

"The governments of the world must immediately stop expanding fossil fuel infrastructure and begin to ramp it down quickly according to a detailed plan - no more vague "net-zero by 2050" sloganeering. This is, of course, what the new IPCC report recommends," Kalmus says. He explained that the reason his group in LA and several others around the world targeted JPMorgan Chase in particular is that it currently funds more new fossil fuel infrastructure around the world than any other bank.

There has long existed an anti-protest bias in the U.S. media, which has also struggled to adequately cover the climate crisis for decades. Which is unfortunate, given that Chapter 13 of the IPCC report also clearly states: "The media shapes the public discourse about climate mitigation. This can usefully build public support to accelerate mitigation action, but may also be used to impede decarbonisation."

But what Fisher's work, along with the larger body of research on social movements, shows is that it's not necessarily publicity that moves the needle where protest is concerned, so much as the size of the crowd and the connection of protest to either civic action (voting, particular policies) or to stopping specific activities (like the building of a pipeline), both of which tend to scare both politicians and corporations into action.

Max Berger, a cofounder of the grassroots organizing incubator Momentum, which helped birth Sunrise, says part of the key to effective organizing is planning. Or in Momentum parlance "frontloading."

"It essentially just means planning, but it specifically means planning for a movement that you hope will decentralize," he says. "So, you know, if you look at movements like Occupy and Black Lives Matter that broke out spontaneously or somewhat spontaneously, they may have a group that really helped kick them off and get them started, but it basically went viral without a plan to operate at scale. And so what ends up happening in my experience is, you know, those kinds of movements decohere very rapidly because there's very little holding it together, because it wasn't really planning to get as big as it got. So basically front-loading is just a process by which you spend time thinking about what do we do if this gets huge? So as people are entering into the movement, you can arm them with the knowledge and the frameworks that they need to operate as part of it even if it gets really big. And I think that's something that has served Sunrise really well — not that you don't have to answer a million different questions and figure things out, it's not like this unfolding protein that just collapses into the shape that it needs to be, but it certainly guides your decision-making once the movement is unfolding in a way that can be really helpful, both for leaders and for even new people coming in the front door to understand, okay, if I sign up for the movement, this is what I'm signing up for. This is why they believe what they believe. This is what we're fighting for. This is how we're going to fight for it. And so it allows you to then take leadership in your local community and make decisions that make sense for your local context while still being part of something much larger and more coherent."

Kalmus has often said we need a billion climate activists, but for now he says he's particularly focused on getting scientists out into the streets. "Earth scientists are finally realizing, I think, that we actually have an important role to play in nurturing and lending legitimacy to this burgeoning movement. One of my main goals, personally, is to help get as many Earth scientists off the sidelines and causing good trouble as quickly as possible."

At the same time that the climate movement is growing, the use of litigation as a tool in the activist toolbox has exploded in recent years as well. There are now more than 1800 climate cases making their way through courts around the world at the moment, more than 1300 of which have been filed in the United States. This IPCC Report for the first time named litigation as a tool for driving policy shifts. "Climate litigation is growing and can affect the outcome and ambition of climate governance," Chapter 13 notes. Elsewhere in the chapter, it adds: "Activism, including litigation, as well as the tactics of protest and strikes, have played a substantial role in pressuring governments to create environmental laws and environmental agencies tasked with enforcing environmental laws that aimed to maintain clean air and water in countries around the world."

So perhaps with a billion climate activists and a few thousand lawyers, and maybe a bit of help from the media, those vested interests might just begin to lose some power.