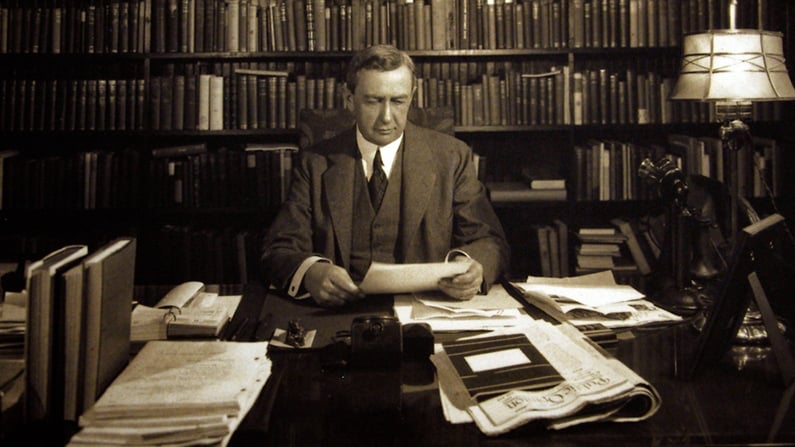

Ivy Ledbetter Lee is widely considered the father of modern public relations (yes, yes Edward Bernays, Sigmund Freud’s nephew, also sometimes claims that prize, but he started his firm 25 years after Lee).

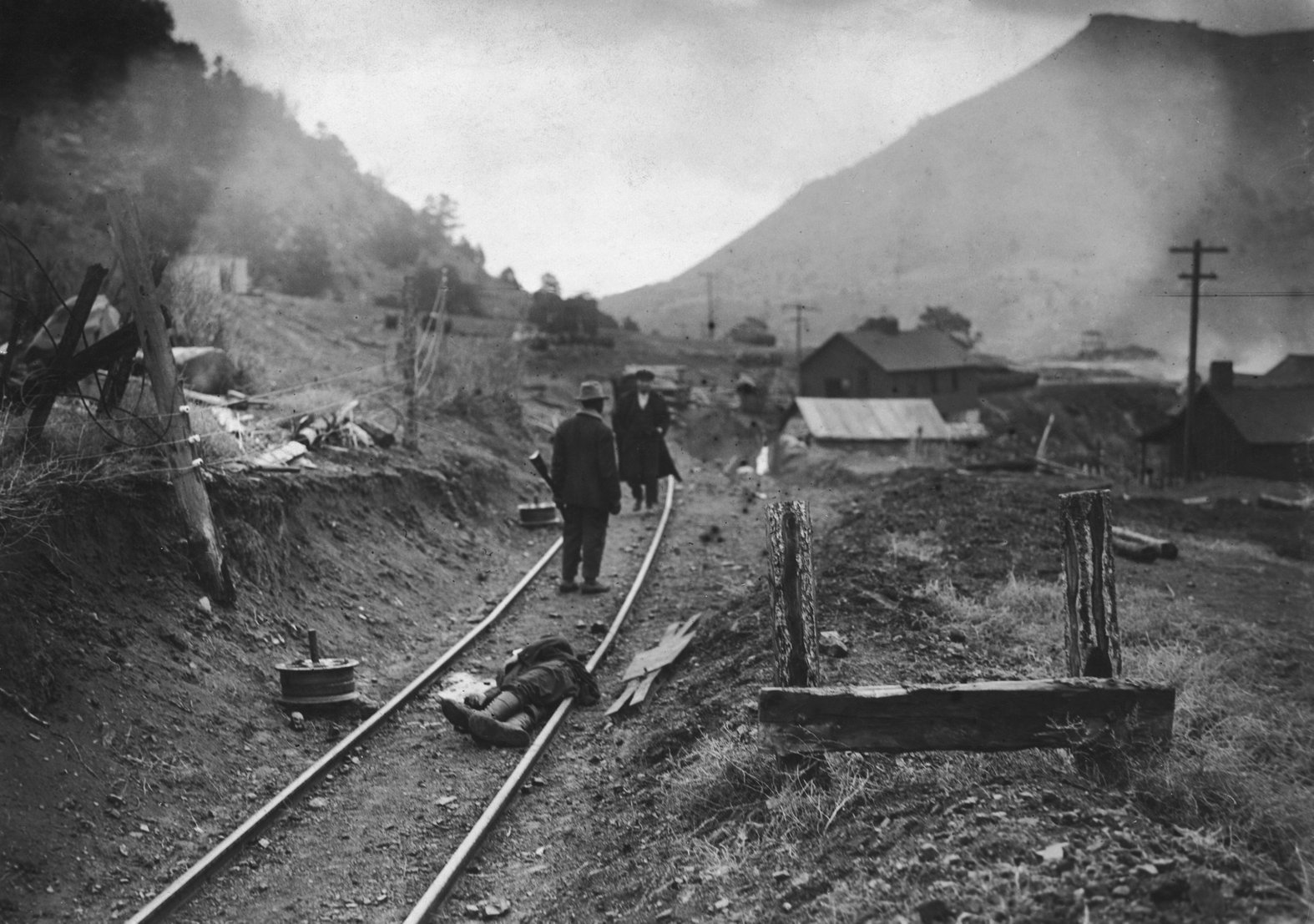

Lee worked for coal companies and railroads and then in 1914 went to work for the Rockefellers. In response to an ongoing strike at a Colorado mine owned by the family, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. had sent in armed guards, who teamed up with the Colorado national guard to bust up the protest. The men invaded a camp of some 1200 miners and their families, and began setting tents on fire, and then shooting at protestors. Ultimately 22 protestors were killed, including 11 children and two women, who were suffocated by smoke when they got trapped in a pit, trying to hide from the gunfire. The incident came to be known as the Ludlow Massacre. The Rockefellers were just a few years out from the break-up of the Standard Oil Trust, and the Ludlow strike quickly made the son as unpopular as his father. They were in great need of a new image, and Ivy Lee was just the man to give it to them.

Archival news photo of the aftermath of the Ludlow Massacre.

Lee went on to work for Standard Oil and the Rockefellers for the rest of his life. After WWI he helped them bring oil companies together into the first industry PR group, the American Petroleum Institute, back in 1919. In 1929, when Standard Oil signed a partnership deal with German chemical manufacturer I.G. Farben, creating Standard-IG Farben, a joint venture that aimed to develop petrochemicals and synthetic fuels, Lee picked up IG Farben as a client too. And when Adolf Hitler began consolidating power in Germany, Farben asked Lee to come to Germany. The $4,000 a year they were paying him was increased to $25,000 a year, and they offered his son a full-time job in Germany, too, for $33,000 a year, big money at the time. Lee met with minister of propaganda Josef Goebbels, and with Hitler himself, along with various other Third Reich leaders, and advised them on relations with the press and with America in general. When the Nazis were planning to kick out the foreign press, Lee advised them against that idea, and suggested they build relationships with the foreign press instead.

Lee also advised them that Americans would never go for the Third Reich’s stance on Jews, but it’s unlikely that he realized at the time how far that thinking went or what it would lead to in a few short years. Lee was brought before the House Un-American Activities Committee to testify about his involvement on “Nazi propaganda” in 1934. The transcript of that testimony is here.

In addition to creating the "crisis actors" narrative we still see in use today and the press release, and launching a whole new industry in the U.S. that then spread around the globe, Lee pioneered the creation of fake expert organizations. On behalf of the railroads in the early 20th century, he created the Bureau of Railroad Economics. The Bureau had the appearance of independence but was created and funded by Lee, on behalf of his railroad clients. Economists at the Bureau would tell newspaper journalists that taxes on railroads or railroad companies were bad, and at the time journalists didn't really think to question this ostensibly independent economic think tank. It's yet another technique we still see all over today.

Biographers of Lee are often torn over whether or not he was well intended. His lofty "principles of PR" are pointed to as ethical touchstones for the industry. We cannot speak to the intentions of a long-dead man, but we can think about the many things he said and wrote himself about the industry he helped to create. Lee was an absolute believer in the power of business to solve problems, of the free market to deliver solutions. His counseling of Hitler was more driven by wanting German and American businesses to keep trading than anything else; ditto his efforts to establish trade relations between the U.S. and Russia. He figured you don't go to war with your trade partners. As a spokesperson for and counselor to industry, Lee always encouraged telling the public the truth, but he also had a very...let's say unusual...understanding of the word "truth" and spoke often about his job being to deliver “my interpretation of the facts" to the public.