Separating the economy, and people, from the environment has always been key for extractive industries in the U.S. A lot of it hearkens back to ideas underpinning colonization, as well as a particular interpretation of the Bible, and the ideals of the Enlightenment. Back in the 1600s, philosophers like John Locke and Renee Descartes explicitly claimed humanity’s dominion over the rest of nature, arguing that our right to use nature for our benefit—not just for sustenance but also for profit—was granted by God. Locke in particular argued for private property, and for property rights to be connected explicitly to extraction. If someone was not working the land in some way, according to Locke that land was empty and up for grabs. As the United States was formed, political leaders were faced with a choice between the John Muir approach to conservation, which saw nature as worthy of protecting because of the beauty and peacefulness it bestows on humans (some humans; Muir certainly did not buck the trend of colonial white men by extending this view to, say, the Indigenous people who had already been enjoying this land for centuries), and Gifford Pinchot who viewed nature as simply another input to the economy

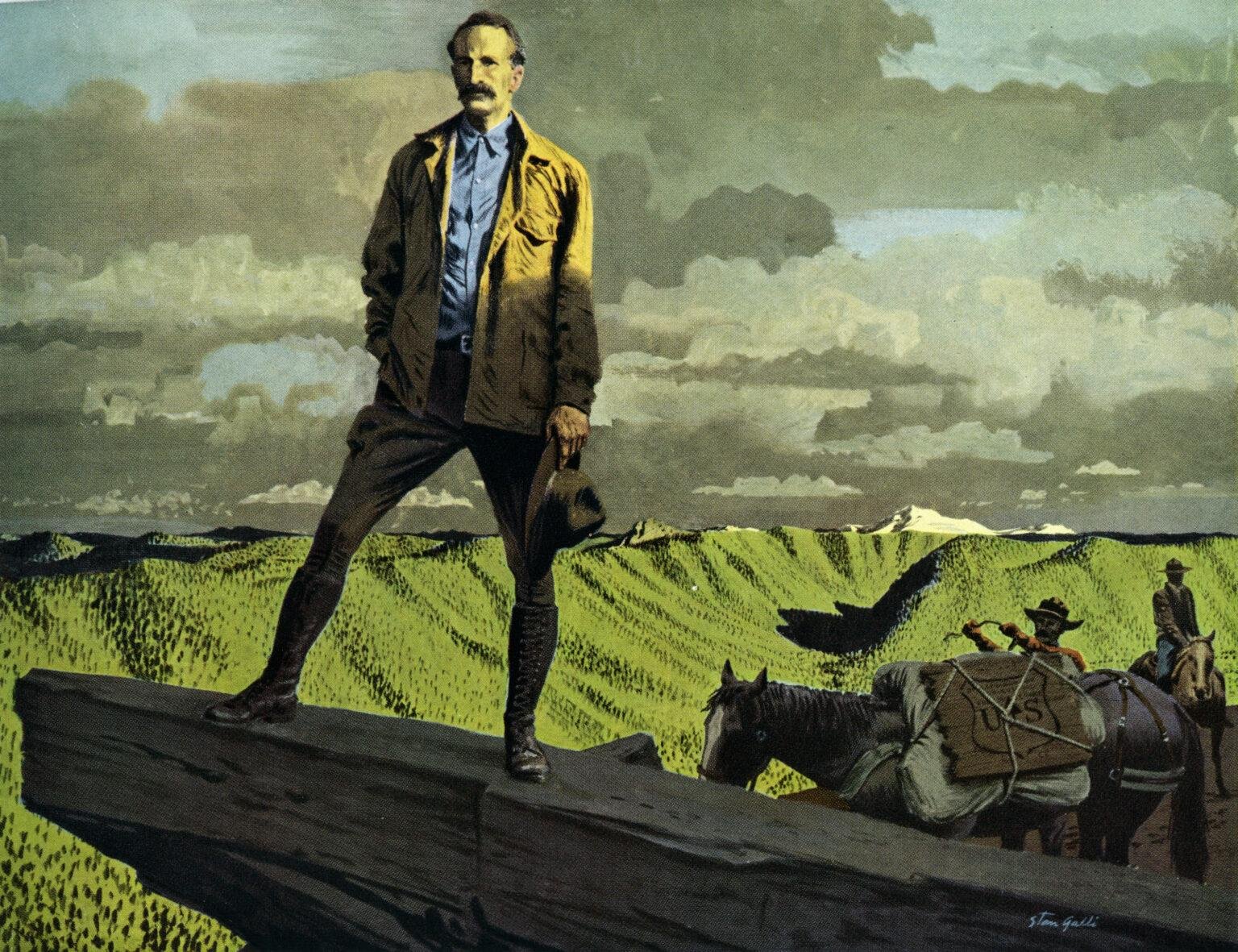

Although less well-known than John Muir, Gifford Pinchot was the United States’ first forester, in the sense of somebody who was professionally trained to manage forests. “And that's really important because it introduces the idea that nature is something that should be managed,” Melissa Aronczyk, media studies scholar at Rutgers University, explains. “ForGifford Pinchot, natural resources were just that: resources. It was lumber that Americans needed for development. It was water that may be needed for serving cities. And there was an economic benefit to protecting forests, but you had to protect them for the service of American enterprise and the American economy.”

Pinchot was not technically a publicist, but he was an absolute expert at managing various publics, which included not only high-level politicians but also the general public, teachers, and scientists. “From the very beginning of his life as a professional forester, Pinchot was constantly promoting himself and his work,” Aronczyk says. “He was very aware of the value of public support for his vision of forestry, and he used every means at his disposal to accomplish that. He wrote textbooks that he expected would be taught from kindergarten on up about forestry. And indeed, they were. There were thousands of copies of his books sold. He created what we would today call, I guess, press events, PR events, sometimes with Teddy Roosevelt, where he would be sure to invite all of the news media of the time to cover the event when he appeared to announce a new policy or in front of an important natural resource. And he also made very close behind-the-scenes connections with lumber operators and others who would then, of course, end up supporting Pinchot whenever he wanted a new policy to be put forward. He was able to show us that forestry was a public matter and that that particular vision of forestry as a resource to be managed was the way to think about nature.”

Pinchot was operating right around the time that coal was booming and the oil industry was just getting off the ground.

There was this perfect storm happening in the U.S. at the dawn of the 20th century, a convergence of factors all leading to an extractive society: a philosophy that extolled the virtues of independence and freedom, and that attempted to understand nature through categorization and classification; a religious narrative that said God has created this land for you; enough wiggle room in both to cast gross inequity as somehow okay; a new economic paradigm in which competition and individual success reigned; seemingly abundant natural resources that needed only to be found and managed. AND a brand new country in which the government was almost indistinguishable from industry.

“Pinchot was really the earliest example of that,” Aronczyk says. “And it's important to think about that because it reminds us that the state and corporations were often very, very much on the same side when it came to talking about nature and the environment.

Extractive industries availed themselves of the burgeoning PR industry early on and in the hands of professional PR guys, these ideological threads were woven into a foundation that underpinned everything from the fight against environmental regulation to the painting of environmentalists as out-of-touch hippies, or elitists on a quest to preserve some rarified ideal of “pristine nature.”

“If you think about the monopoly companies of the early 20th century, these were mainly in heavy industry: rail, steel, coal, and oil,” Aronczyk says. “And these industries relied on the favors of the government to achieve their size and their power. So as we know now, of course, those industries were also terrible for the environment. And we also know that back in that era and what you call the progressive era, Americans were becoming increasingly worried over the size and power of corporations. And so we could think about how public relations was essentially designed to reassure Americans that these companies were good citizens and that their vision of how to use the environment as a resource was the right vision.”

The fossil fuel industry spent a lot on PR from its early days, but you see that spending ramp up quite a bit after World War II, particularly in service of making sure that Americans understand the need to prioritize the economy above the environment…never mind that the two are deeply intertwined.

From school curricula to short films, industry presentations to media interviews, this theme has been hammered again and again for decades. Even the economic studies industry spokespeople point to as proof that taking care of the environment is bad for the economy were commissioned by industry groups like the American Petroleum Institute.

“You know, the PR techniques they're so smart and going like one or more steps above the level of just the thing you're trying to sell to really shape the context we’re all operating in—don’t sell water, put people in the desert,” says Ben Franta, head of the Climate Litigation Lab at Oxford University, and author of the paper “Weaponizing Economics” about how the fossil fuel industry and its PR firms hired economists to create models and papers that emphasized the value of fossil fuels and downplayed the cost of pollution. “The development of neoclassical economics basically asserted that the economy left to its own devices would spontaneously find an equilibrium that was optimal. Or natural, at least. In many ways that theory was formulated as a scientific defense against Marxism.”

Ivy Lee, the godfather of public relations, pioneered the use of shoddy economics for PR, creating the Bureau of Railway Economics to help his railway clients push back against regulations. Staffed by real economists, the Bureau would put out white papers and reports on how proposed wage hikes for rail workers would make goods more expensive for the public, or how regulation would harm the rail companies and every industry that worked with them. Journalists had no idea the bureau was funded by the rail companies and quoted its experts as credible disinterested third parties.

In the 1950s, 60s, and 70s oil companies spent millions of dollars creating curricula, from Amoco’s “Kingdom of the Mochans” which paints anyone who cares about the environment as primitive and backwards (with a layer of racism on top) to Phillips Petroleum’s “American Enterprise,” used in high schools throughout the U.S. in the 1970s to teach the basics of the economy…which include of course a reliance on fossil fuels and an understanding that industry and jobs must be prioritized over trees and water.

These projects subtly deliver the message that American freedom is the product of extractive capitalism. A slideshow dug up by Carroll Muffett, the CEO and president of the Center for International Environmental Law, lays bare some of the thinking behind this messaging. It’s part of a presentation given to the Society of Petroleum Engineers in the early 2000s, which Muffett shared with Drilled and Earther as part of our “ABCs of Big Oil” series. It was made by John Tobin, a well-known oil industry consultant, for an industry-backed group called the Energy Literacy Project. In it, Tobin lays out the idea that public education about energy can help the oil industry maintain its social license to operate despite scientists’ increasingly dire warnings about the role it plays in driving the climate crisis and growing public desire to get off fossil fuels. In his words, “the industry can be profitable in spite of its image.”

“The public’s perception of the industry has been abysmal for years,” Tobin told us. “And getting a more positive view, starting in K through 12 and keeping going, including adults and so on? We like to call it … developing science-savvy citizens, that will be able to make informed, well-reasoned decisions on their prudent use of natural resources, oil and gas in particular, and be able to make well-reasoned decisions on how they want to see the industry regulated.”

In the presentation, he specifically outlines an approach called the three Es, which he calls “a path to an improved image (and, potentially, improved profits).” The Es stand for energy, economy, and environment, and it seems they’re in that order intentionally.

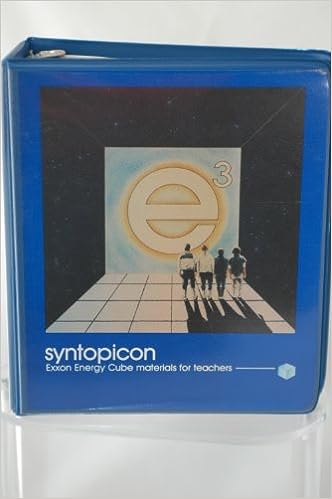

The idea is that every policy decision must weigh the impact on each of these three facets of human life. Exxon used this three Es paradigm, too—they called it the “energy cube.”

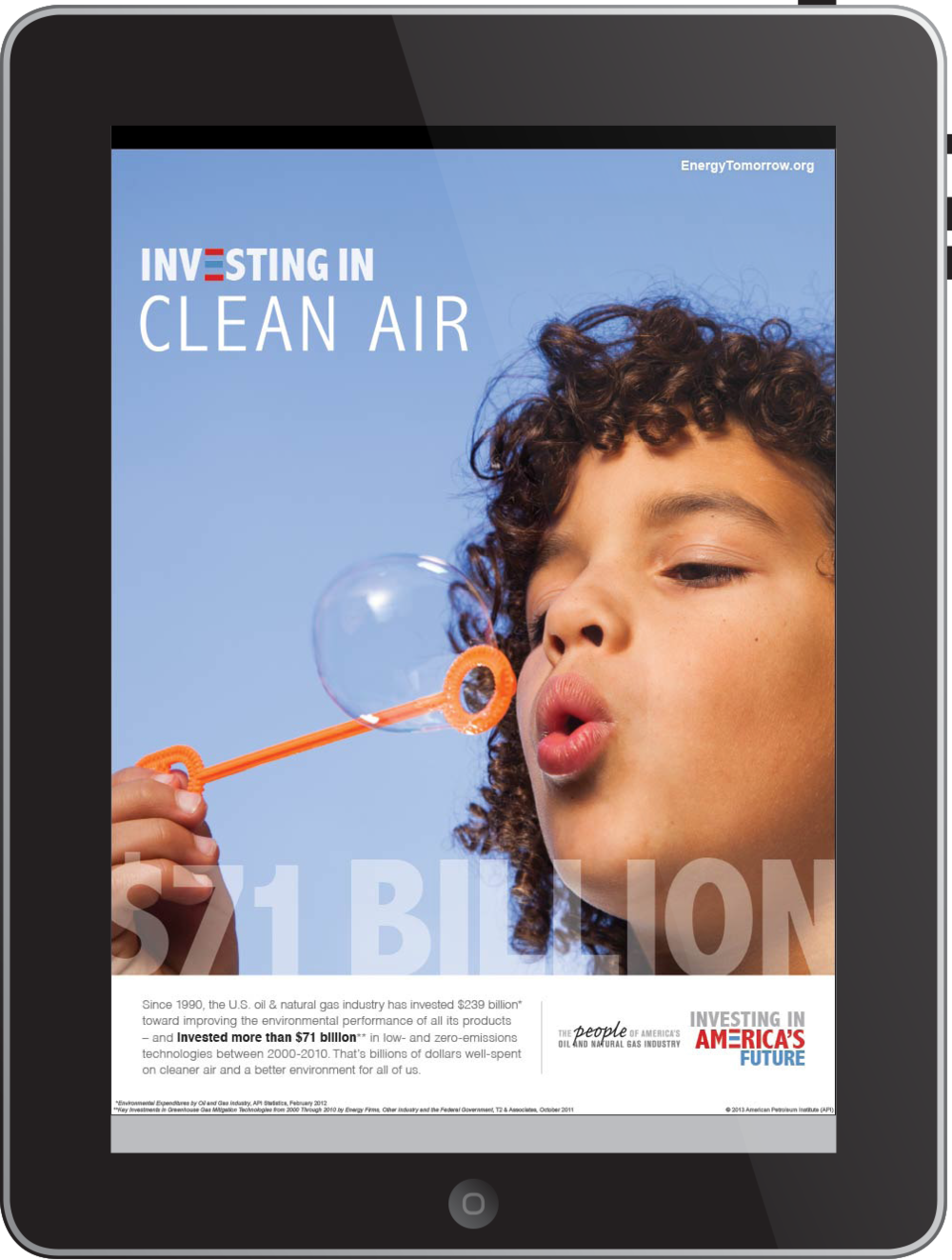

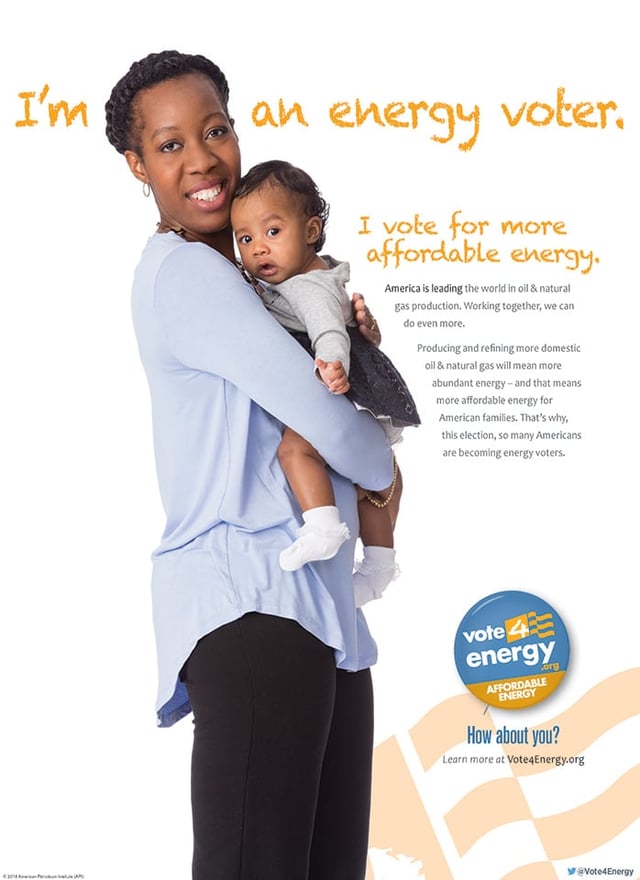

Today the “three Es” paradigm shows up in ads, social media campaigns, and media interviews, too, alternately emphasizing the industry’s job creation capabilities, the importance of prioritizing economic concerns, and the industry’s prowess at balancing its massive environmental impacts with discreet, contained conservation projects.