The very first industry-funded school broadcast in the country was the Standard School Broadcast, put out by Standard of California (now Chevron) from 1928 to the 1960s. The oil industry in particular has been very involved in shaping school curricula over the past 100 years, an effort that really ramped up in the 1950s.

“Pretty much from World War II on, the American Petroleum Institute has been actively pushing outreach to schools, and really trying to get their viewpoint about energy and petroleum into schools,” says Robert Brulle, visiting professor at Brown University. “Certainly they were doing that a lot by the 60s and those efforts continue to this very day.”

Lots of other industries have gotten into the business of creating activity books and curricula that put particular brands and products in front of the next generation of consumers and voters too. In her book Hucksters in the Classroom: A Review of Industry Propaganda in Schools, Sheila Harty highlighted the efficacy of "imprint conditioning," the subliminal impact of advertising. Kids—and their parents and teachers—might not think an industry-funded video or coloring book or lesson plan has had a big impact, but Harty writes, "the next time we go shopping, one brand name or label looks more familiar. and we choose it like an old friend."

In The Hidden Persuaders, Vance Packard quotes a marketer encouraging his colleagues to embrace this new strategy: "Eager minds can be molded to want your products! In the grade schools throughout America are nearly 23,000,000 young girls and boys. These children eat food, wear out clothes, use soap. They are consumers today and will be the buyers of tomorrow. Here is a vast market for your products. Sell these children on your brand name and they will insist that their parents buy no other."

The photos below are from a comic book that Disney put out in conjunction with Exxon in the 1980s, at the same time that Exxon was sponsoring the Universe of Energy Center at Epcot. Both were aimed at shaping kids’ understanding of energy and the economy.

This one has an energy conservation theme—and also makes the point that solar and wind are, you know, meh.

Exxon’s Universe of Energy Center was at Epcot from 1982 through 1996. That’s fascinating, because that’s the exact time span that Exxon went from researching climate change to explicitly denying it. (Exxon’s denial started in the late 80s and picked up steam throughout the 90s). The exhibit was originally intended to be called The Future of Energy, and was supposed to focus only on renewable energy, but when Exxon got involved they changed the scope to include fossil fuels as well, and present an "all-of-the-above" approach to energy. Sound familiar?

This exhibit touting fossil fuels opened in the same year that Exxon’s manager of environmental affairs, M.B. Glaser, sent a memo out to company executives about the greenhouse effect. This memo noted that fossil fuel combustion, along with clearing of virgin forests, were the primary contributions to the warming trend.

The memo added: “Our best estimate is that doubling of the current concentration could increase average global temperature by about 1.3 degrees Celsius to 3.1 degrees Celsius.”

“[Exxon] put out these in conjunction with Disney to teach kids about renewable energy and energy conservation and environmental concerns,” says Carroll Muffett, the president and CEO of the Center for International Environmental Law. “And it's perhaps unsurprising that what children learn from Mickey and Goofy about energy conservation and environmental concerns was we really need gas, we really need fracking, we win. Nuclear energy is fine. There are a lot of problems with wind and solar. It may work out eventually, but thank goodness for this bountiful resource of oil, gas and tar sands.”

Exxon wasn’t the only one using comic books to reach the youths. In the 1970s, Amoco put out a wildly racist comic book about “The Mochans,” a “primitive” people who wanted to do unseemly things like use renewable energy. The comic was released as part of a study guide for 7th to 12th graders studying economics—which Amoco graciously provided 40,000 copies of to Indiana public schools.

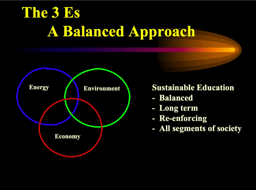

“The industry was teaching kids to be skeptical of regulation, skeptical of the agendas of environmentalists or people who were socially concerned, from their very earliest ages,” Muffett says, “and [they were] constantly emphasizing that anyone who talks about the environment, who talks about human health, should immediately be weighing that and defending it against the economic costs.”

These are the same refrains the fossil fuel industry uses today in its various attempts to shape the minds of young people, both in schools and in the media. And it’s reflected in the way most political pundits seem to think about what’s possible for climate action. You want to preserve a livable world? Well, how much will it cost?

Here’s one more example of the oil industry getting into teaching economics: Phillips’ Petroleum’s American Enterprise educational film series—hosted by none other than William Shatner. (I got my hands on the VHS and digitized it, scroll down to watch all five parts.)

The subtitle is: How Did this America, in its 200 Years of Independence, Become a Nation of Supermarkets, Stock Markets, Skyscrapers and Split Levels; A Country With the Greatest Economic Output in the World?

Phillips took a hands-off approach with the film series in order to make sure it would be acceptable in classrooms.

Instead of developing it themselves, the marketing company that produced it for them contacted economists and historians who helped them put together a five-part series that enthusiastically affirms capitalism. And the series was an unmitigated success. It was picked up by 10 different state education TV programs, and more than 50 percent of the country’s secondary schools had booked the series by 1978, two years after its 1976 release. By the end of 1978 it had been seen by more than 5 million American high school students.

The New York Times ran a story on the series in 1976 as it was being released, calling it, “the latest contribution to the ongoing business effort to interest the American people in the free‐enterprise system.” (See our post on Earl Newsom for more on that front).