Image showing at least 20 drums of pure chemical bromoform imported into Australia by Sea Forest, including “hazardous materials” stickers.

An Australian company that pioneered the cultivation of seaweed as an all-natural way to reduce methane emissions from livestock quietly imported 4000kg of synthetic bromoform marked “for industrial use only” during the critical early years of its development – enough to feed 34 million cows the methane-busting dietary supplement.

For years Sea Forest has served as the quintessential example of Australian green capitalism. The $139.58m (USD $91.33m) company was founded in 2018 by fashion entrepreneur Sam Elsom and mining industry executive Stephen Turner to cultivate Asparagopsis, a species of Australian seaweed that produces a chemical which inhibits methane production in livestock when fed to them. The seaweed’s methane-busting properties were first identified in research by Australia’s peak scientific agency, CSIRO, that found it to be a naturally-occurring source of bromoform. Bromoform blocks the creation of methane in the digestive system of livestock and is administered either by directly feeding cows seaweed in addition to their regular diet or by processing seaweed to extract the chemical to manufacture a feed supplement or related product. These manufactured products can take the form of an oil that is added to livestock feed or lickblocks that better able doses to be delivered.

According to the CSIRO’s early work, around 5 percent of the world’s total greenhouse gas emissions originate in the digestive systems of livestock and in Australia this process is considered to contribute 11 percent to the country’s greenhouse gas emissions – although local industry has challenged the methods used to attain those numbers. Over a 20-year period methane is 80 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

A Drilled investigation has raised questions about how the company represented some of its activities in its earlier years as it was developing its core product range. Images shared with Drilled show two tonnes of pure chemical bromoform stored in a shipping container bearing the Sea Forest logo at the company’s Swansea site in Tasmania sometime around December 2020. Other images taken inside the container appear to show smaller vials of Bromofom bearing the name “Elsom” on the label and labels on the side of barrels that specify the chemicals were “only for industrial use”. Customs information obtained by Drilled shows that the company also imported another two tonne shipment of pure chemical bromoform from Chinese manufacturer Henan Tianfu Chemical Company in 2021 weighing 2154kg and held in 20 drums. This represents enough chemical bromoform to produce an equivalent of 200,000kg of methane inhibitor. The company repeated the order the following year.

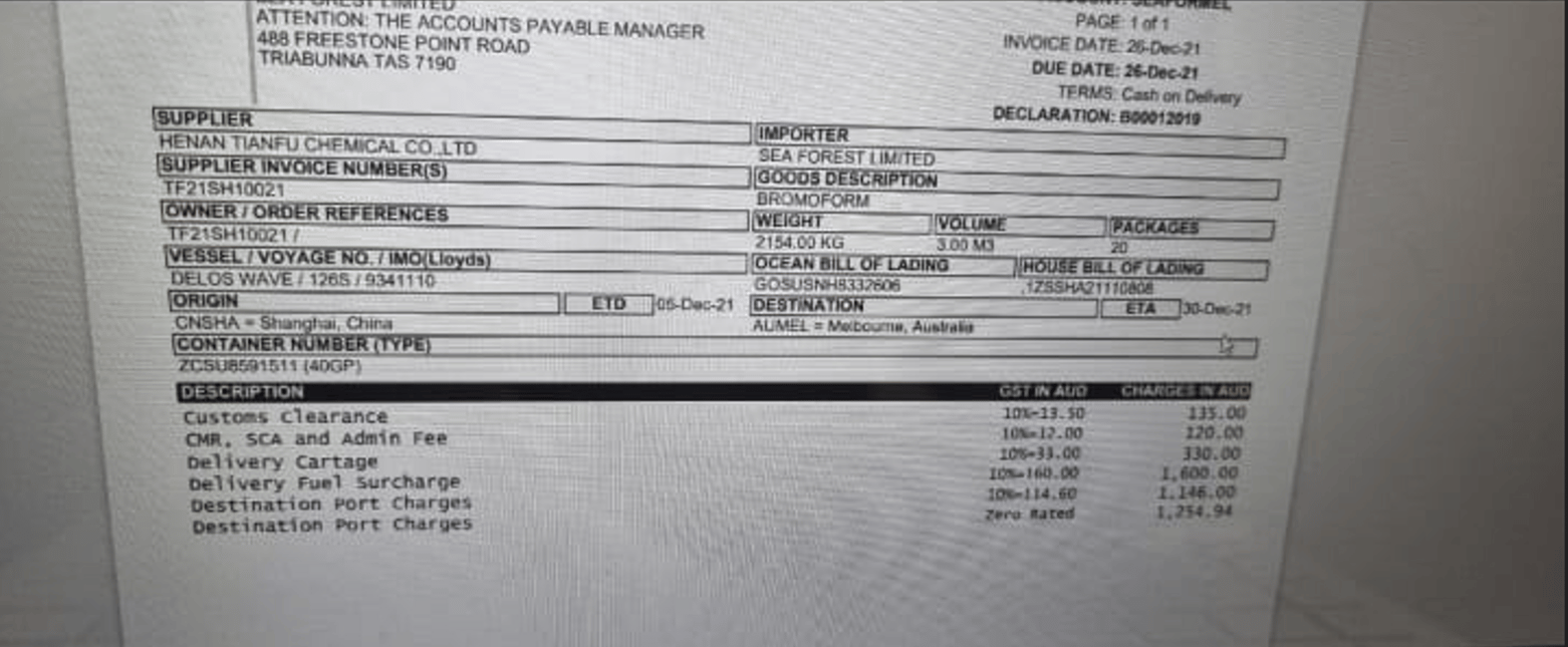

Image of customs information detailing the importation of 2000kg of pure chemical bromoform from an industrial supplier in China.

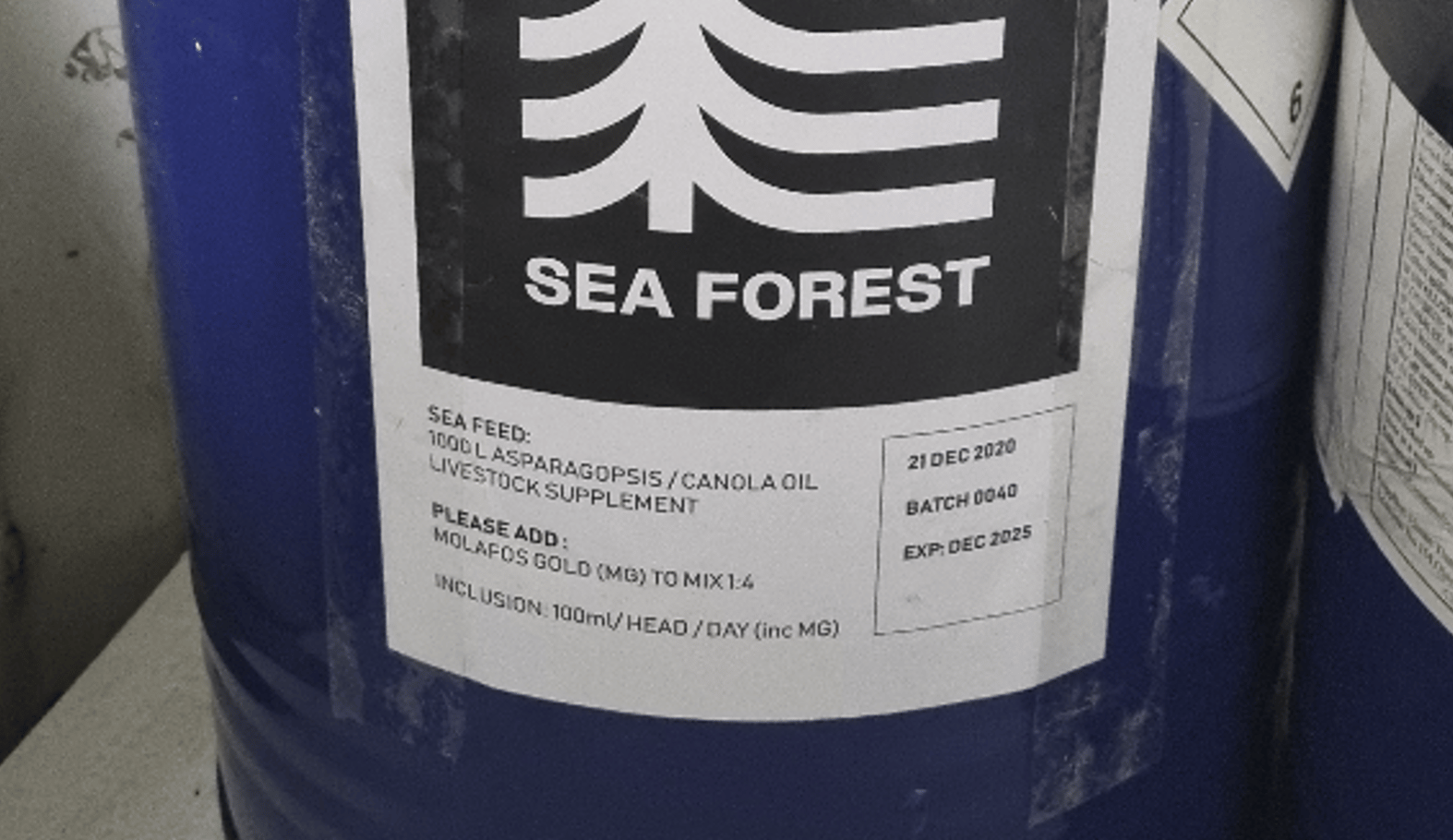

Around this period, Sea Forest was offering dried seaweed that could be added to livestock feed, and working to develop other methods of delivery such as extracting bromoform from seaweed and suspending it in canola oil so it could be administered in a more controlled manner. How its substantial chemical stock eventuated, who ordered it, or its intended use – for example, whether an honest mistake was made in ordering inventory for research purposes, in primary manufacture, to add to products to ensure a consistent concentration of bromoform was achieved, or as an emergency back-up to meet contractual obligations if the need ever arose – remains unclear.

So far the company has not offered specifics. Drilled contacted Sea Forest multiple times to ask about the shipment and ask how it was used. Though company representatives were forthcoming and transparent on some questions, they offered generic or contradictory statements in response to others. Sea Forest director Stephen Turner confirmed the company had imported 4000kg of pure chemical bromoform in two shipments, saying the chemical was used as part of the company’s research and development program. Turner said the company had also bought four smaller quantities from within Australia, amounting to two shipments of 1kg, one shipment of 2kg and one shipment of 10kg. Half Sea Forest’s stock of pure chemical Bromoform purchased from China was stored at its 30 hectare Swansea facility, a former abalone farm the company bought and eventually redeveloped to enable the land-based cultivation of Asparagopsis, with the second shipment stored at a facility in Melbourne, he said.

“They were later delivered to the Swansea facility, and then when facilities were established, transferred to the Triabunna facility,” he said.

Asked repeatedly to clarify whether Sea Forest used its stock of pure chemical bromoform to augment or manufacture its products, Turner said: “Sea Forest produces SeaFeedTM containing bioactives extracted from seaweed and also produces SeaFeedTM containing manufactured bioactives. These compositions, although chemically identical, are each clearly labelled and described in the product disclosure documentation.”

“So Sea Forest has used manufactured products and this has been fully disclosed,” he said.

He added that Sea Forest still held 80% of its pure chemical bromoform stock and that the two quantities had been “imported for the purpose of Research and Development at a time when we were aiming to grow bromoform and iodoform in tobacco plants utilising CRISPR gene editing technology”, but that “this did not eventuate.” In response to follow-up questions about how the other 20% – equivalent to some 800kg of chemical – was used during research employing the CRISPR technique, Turner said that he had only pointed to the CRISPR technique as “one example of the wide scope of alternatives Sea Forest has explored.”

“With hindsight [we] should not have purchased this much,” he said.

Image showing a shipping container bearing the Sea Forest logo at its Swansea site where the company stored its chemicals for a period of time.

Claims that the chemical stock was intended for the company’s research program, however, were contradicted by Sea Forest’s chief scientist Rocky de Nys who, in an interview with Turner present, said he was aware the company had purchased stocks of chemical bromoform as part of its broader research program, but was not aware that it purchased two separate 2000kg shipments, a year apart, until “after arrival”. Asked about how much bromoform Sea Forest would use as part of the company’s research program generally, he said the amounts would normally be measured in “millilitres, grams”. The company’s head of research and development, Masayuki Tatsumi said he could not recall any specific purchase but would have been “definitely aware” of any orders placed after he joined the company. Asked about the company’s past research efforts using CRISPR gene editing technology to modify tobacco plants, Nys said the company’s efforts in the area were limited.

“We never did anything in that space other than read a couple of publications and think, ‘Wow, that’s an interesting idea,’ but we never pursued that. We always had a marine focus with Asparagopsis,” he said.

Turner sought to clarify that he had only suggested CRISPR as “one example” of the research pathways the company pursued during development to illustrate the depth of its efforts, but did not provide any further information about what activity or application might require the purchase of four tonnes of pure chemical bromoform.

Bromoform is related to iodoform, a chemical sometimes used in labs as a disinfectant and for veterinary purposes, and chloroform, a chemical commonly depicted in popular culture. When directly exposed to air, it evaporates similar to hand sanitiser. It is considered toxic in high concentrations, and is a suspected carcinogen. Australia has no specific rules or regulations around the handling or storage of the material beyond requiring the chemical to be stored in a well-ventilated space, the use of proper protective equipment, ventilation hoods and extractors as directed in standard Material Safety Data Sheets.

Professor Fran Cowley, a ruminant nutritionist at the University of New England, said that as a methane inhibitor, there is very little difference in outcome between feeding cows dried seaweed or products made from synthetic bromoform, a chemical that can occur naturally and as a common byproduct in industrial processes such as chlorination in water treatment. Broadly speaking, Cowley compared any wider industry shift from farming Asparagopsis in the ocean to synthetic manufacture, to the production of aspirin; once the painkiller was made from stripping bark from willow trees but today it is produced synthetically in large volumes and sold cheaply. Her own research, some of which has been undertaken in collaboration with Meat and Livestock Australia and Future Feed, and has involved Sea Forest products, showed that bromoform consistently worked to inhibit methane, that there was no noticeable differences between the source of bromoform and that it safely passed through a cows digestive system.

“It’s incredibly effective at inhibiting methane; depending on the dose, the completion rate, you can inhibit methane emissions, using the whole seaweed or bioactives in oil,” she said. “There’s no sign of residue of bromoform in meat.”

Cowley noted that Sea Forest’s Asparagopsis-derived products face stiff competition from existing products such as Bovaer. Produced by Swiss company DSM-Firmenich, Cowley said Bovaer is cheap to produce, buy and is associated with a body of peer-reviewed research making it the “gold standard” for methane-inhibitors. Bovaer is a separate feed additive developed by Dutch chemical company DSM-Firmenich, and made from a synthetic chemical compound known as 3-Nitrooxypropanol that acts as a methane inhibitor. Though Bovaer has been targeted in online misinformation campaigns overseas, it is used worldwide. In Australia, however, she says it is little known outside of livestock producers. Asparagopsis-derived products have captured the public imagination thanks in part to the Australian-connection with early research, she said.

Drilled contacted multiple former Sea Forest employees, most of whom declined to comment on the record, saying they had been made to sign non-disclosure agreements (NDA) and non-compete clauses as part of their employment contract, or that they might face personal or professional retaliation in some capacity. Turner said Sea Forest’s use of non-disclosure agreements and “tiered non-competes to protect its IP” was “normal practice for science and other innovation companies”.

One former Sea Forest employee, Margie Rule, who currently works as a consultant for seaweed producers in Australia and did not sign an NDA as part of her work with the company. She left Sea Forest in April 2021 after company management did not respond to two requests to formalise her employment contract and she successfully sought a job with a rival seaweed farmer founded by Australian iron ore billionaire Andrew Forrest. Rule said she was unaware that Sea Forest had imported such large quantities of pure chemical Bromoform from overseas during her time with it, adding that, in her experience as a consultant, this was unusual among seaweed growers and out of step with broader industry practice.

“My god!” She said. “That’s massive. According to the first 2020 CSIRO study, the seaweed there contained 6.55mg of bromoform per gram, and when they fed the cows approximately 18g, they found a 98% reduction in methane.”

“If Seaforest has four tonnes of pure bromoform, that could produce 34 million doses. Even if they only used 20%, this would still feed 6.8 million cows according to that original feed rate. This would be the equivalent of 122 tonnes of Asparagopsis.”

“I don’t know why you would buy that amount of chemical bromoform if you were growing enough seaweed.”

Image showing a label with information printed on the side of a drum of pure chemical bromoform with the words “only for industrial use”.

Rule, whose PhD involved the propagation of seaweed, worked with early Sea Forest teams that pioneered the use of rope to help grow Asparagopsis in the ocean. She said that despite hope that the leafy-stage of the Asaparagopsis lifecycle could be grown all year round, and that its high growth rate would sustain rapid cultivation, it proved too sensitive to environmental conditions outside a controlled environment, including temperature, light, nutrient load, depth, wave action, salinity and time of year. Rule recalled that early attempts to grow Asparagopsis were “timed perfectly” and a success, but other attempts failed owing to variations in timing or conditions in the marine environment that could not be controlled for.

In one incident in December 2020, Rule said she was called into a meeting after an Aparagopsis crop failed where she was grilled by company leadership who, she says, suggested she was to blame for the die off. Rule – who compared the current state of knowledge in cultivation of Asparagopsis to the early stages of rice or wheat cultivation in earlier periods of human history – said that research work had not yet pinned down the seaweed’s growing period, but was ignored when she tried to point this out for company leadership. In an email dated January 2021 and seen by Drilled, the company’s science team acknowledged internally that Asparagopsis’ growing season had yet to be established. Other former employees recalled that at this time, the company struggled to produce enough seaweed to match its ambitious production targets – a claim Sea Forest has repeatedly and strongly denied. The company does, however, acknowledge that frequent marine heatwaves along Australia’s southern coast made ocean-cultivation of Asparagopsis increasingly difficult in later years.

During this early period, the company was firmly focussed on brand building, Rule said. In one example, she described how production staff and technicians were asked to wear specially-embroidered long white lab coats when participating in photo shoots and other public appearances. She also recalled that she and others were given pens to wear in their pockets during photoshoots to “make us look more sciencey”. In another example, Rule recalled the company sought to collect samples of wild Asparagopsis that could be clipped and re-grown in a controlled environment to build up its stocks. At this time, the company sought to collect wild samples of Asparagopsis tetrasporophyte, an intermediate life stage of the plant commonly referred to as “pom poms” that present as fluffy red buds. These pom poms are considered to contain a higher percentage of bromoform than the leafy-stage of the seaweed lifecycle. However, the wild pom pom samples were frequently contaminated by Polysyphonia pom poms, another species of red, leafy seaweed that look similar to Asparagopsis.

“A good comparison is the difference between gold and fools gold. It’s really easy to confuse them if you don’t know what you’re looking for and don’t have a microscope,” Rule says. “The same is true for these seaweeds.”

At one point, the team sought to identify and remove this Polysyphonia, temporarily storing it into a separate tank as a step towards disposing of it. Rule said she and other staff were then asked by Sea Forest management to maintain the tank for testing purposes.

The tank containing Polysyphonia was later shown to media and other visitors to the facility, Rule said. One article published by The Weekly Times on 28 April 2021 included a photo of Sam Elsom standing next to a land-based tank. The caption read: “Sam Elsom with on-land tanks where growing asparagopsis [sic] seaweed is being trialled. Harvesting the seaweed (below, left) offshore”. Rule said this tank held Polysyphonia at that time, that she had helped place the other seaweed in the tank, and that she was later tasked with providing samples of wild Asparagopsis from another part of the operation for use in close-up photos.

“The company always did collections from wild populations before photo shoots,” Rule said.

Rule also pointed to social media posts from March and August 2021 that depicted similar scenes, and another post from June that year which appeared to show Elsom viewing the same tank while on a tour with a potential investor.

Screenshot of image published by The Weekly Times in an article that appeared on 28 April 2021 about Sea Forest and its activities.

Sea Forest director Stephen Turner rejected this version of events, saying Sea Forest “never showed members of the media, investors or other third parties tanks holding Polysyphonia while representing it as Asparagopsis”. He also rejected any suggestion the company’s activities had created a “false perception” about the nature of its operations.

“The company has not created a false perception of what its actual activities entail, and has aimed for clear communication of its journey from closing the asparagopsis life cycle, establishing commercial farming in both the marine and then the land based environments, extracting the seaweeds bioactives, experimenting with edible and nutraceutical seaweeds, growing at scale macrocystis for giant kelp establishment, stabilizing the bioactives in oil and water (water is still in R&D at trial stage) and replicating those bioactives,” Turner said.

However, Turner said that Polysiphonia was “used in inoculating” tanks “prior to stocking them with Asparagopsis,” noting that the tanks at its Triabunna facility were stocked with Asparagopsis “from 5 October 2021 onward”. This occurred after the publication of the article and other social media posts showing site visitations where tanks of Polysiphonia were viewed by visitors.

Sea Forest later shifted its operations from ocean-based cultivation to growing seaweed in land-based tanks that offered better control over conditions. Built on the site of an old abalone farm, its Swansea facility repurposed existing infrastructure that enabled it to draw in water from the ocean, circulate it through the pens to cultivate the seaweed, and then release it back into the wild. This process enabled closer control of environmental conditions and by all accounts the company was successful in mastering the process.

Current and former employees who were involved with the company around this time described how, by 2023, a new problem had emerged: oversupply. At that time the company publicly expressed frustration about a lack of demand for its products – one news story described its offering as a “golden elixir” – saying it had ten months to move its stock before they reached the end of its shelf life. This formed part of a broader call for the government to establish programs that pushed livestock producers and the dairy industry to cut methane emissions.

In January this year, however, it began to pivot its operations. Sea Forest formally stopped operating its Asparagopsis marine farm “to fully concentrate on land-based production” of pom poms, partly as a result of recurring marine heatwaves driven by climate change. By April 2025, staff working in the marine cultivation of the business were made redundant. The company has since sold one of three boats used to hang its grow-ropes, with another one currently for sale.

Company documents published on the Australian Stock Exchange when Sea Forest went public in late November suggest its hand may have been forced. Over its lifetime, the company has been privately backed by Australian investment bank Macquaire, billionaire Peter Gunn and entrepreneur Zoe Foster Blake and her husband, but over the last two financial years, the company booked a combined loss after tax of $15,975,720 (USD $10,453,712). In promoting its public offering, the company said it now planned an expansion, with new blending and distribution facilities to be built in the Australian states of Queensland, New South Wales, Western Australia and South Africa. According to its 2024 and 2025 annual reports, however, Sea Forest sold as much oyster spat as methane inhibitor. The company reported that it was working to resolve this lack of a market, saying it had made “substantial progress towards commercialisation” but warned that “its ongoing ability to continue as a going concern, recover the carrying value of its assets and meet its commitments as and when they fall due is dependent upon securing additional funding.”

This dynamic raises certain questions about the underlying business model Sea Forest has pursued, and by extension pioneered for other seaweed producers. An easier, less risky and possibly more profitable path to growth might have been to import and repurpose bromoform, an industrial byproduct, into a methane-inhibitor from the outset–but then the initial vision for Sea Forest was not to become an Australian Monsanto. With a corporate identity built around seaweed cultivation, the promise of an all-natural climate solution differentiates its product from competitors and has allowed the company to secure millions in competitive venture capital and government grants to support its growth. With unanswered questions about its practices and clear financial pressures, Sea Forest shows the extent to which green business remains business – and perhaps how easy it can be to become trapped by expectations.