The first hearing in Greenpeace International’s anti-SLAPP suit against Energy Transfer begins in Europe today. The international environmental nonprofit claims the suit Energy Transfer filed against it in state court in North Dakota amounted to a SLAPP—Strategic Litigation Against Pulic Participation, a harassment suit meant to dissuade the company’s critics. Meanwhile, Greenpeace USA is in the process of appealing the verdict in the suit in question, which resulted in a March ruling ordering the organization to pay the pipeline company some $666 million in damages. The suit alleged that Greenpeace, not the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, had orchestrated the 2016 and 2017 protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline, despite the fact that Energy Transfer’s attorneys only ever managed to document around $150,000 in donations flowing from the nonprofit to organizers on the ground, and a couple of non-violence trainings. The suit also included defamation claims, alleging that Greenpeace defamed Energy Transfer by stating that the pipeline company destroyed sacred sites in the construction of the pipeline, that the pipeline threatened the Standing Rock Sioux tribe’s drinking water source and that the pipeline would exacerbate climate change. Those last two claims were dropped when Energy Transfer was pressed to provide documentation that they weren’t true.

Drilled’s current podcast season traces this case from the early days of the Standing Rock protests in 2016 to today. In today’s episode, we dig into what Energy Transfer might have been trying to hide by keeping the discussion of water and climate change out of court. Listen below, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Transcript

Alleen Brown: [00:00:00] It is an unseasonably warm day in October, 2024. Rolling hills covered in golden grasses stretch on either side of Highway 1806 on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, and I'm riding in a truck with Doug Crow Ghost. He leads the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's Department of Water Resources. Behind us is a truck pulling a pontoon boat.

We're with a crew of people heading to the Missouri River, about 10 miles downstream from the Dakota Access Pipeline, which Doug calls DAPL.

Doug Crow Ghost: We're documenting that if there's a pipeline break, DAPL is saying that they can get these big skimmer boats on the water to go up there, to start getting rid of the, uh oil. And we've been saying, hell no. There's no way. But we're gonna document it anyway. And we are gonna drive along, take pictures of, there's some certain they call 'em, uh...

Alleen Brown: They're trying to find out if the Missouri River is high enough so that emergency [00:01:00] boats could clean up an oil spill. But the catch is for our plan today to work, we have to be able to get our boat on the river.

And as we arrive at the marina, it becomes clear that a pontoon ride might not be happening today. Doug starts chatting through the window with the local guy.

Doug Crow Ghost: Are you freaking kidding me? It's, you can't, it's unusable.

Alleen Brown: The water level is too low.

Doug Crow Ghost: Do you think you could get that, uh, pontoon in there? I know it.

No way it's soft there, but might get stuck. Yeah. He ain't gonna get no pontoon in there. Yeah. See this shit show

Alleen Brown: To some degree, this proves Doug's point. He figures that if we can't even get the pontoon on the water, then Energy Transfer isn't gonna be able to launch big, heavy emergency boats to skim away oil.

Doug Crow Ghost: I, I drove out here last week to check it out and it was good.

Boat ramp guy: Yeah last week it was...

Doug Crow Ghost: Alright then. Well, shit,

Boat ramp guy: I don't want you guys fucking have a shit show over there.

Alleen Brown: Doug's a big talker and he's got his hands in a lot of things. As the Standing Rock Tribe's Water guy, the Dakota Access Pipeline has been a big part of [00:02:00] his job. To the Standing Rock Nation, the pipeline is among the biggest threats to its primary drinking water source, the Missouri River. So Doug spent countless hours trying to make sense of Energy Transfer's emergency plans, what they intend to do if the oil leaks out. He's also helped with the tribe's ongoing legal fight against the pipeline.

In late 2024, standing Rock is getting ready to file a new lawsuit to stop the flow of oil. And the water level measurements they take today are meant to help prove that the pipeline is unsafe. We get out of the truck and inspect the water line.

Doug Crow Ghost: Look, look at how far it went down just for this not even to be dried yet.

Alleen Brown: How would that happen?

Doug Crow Ghost: The Army Corps of Engineers. The mismanagement of the river.

Alleen Brown: The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's legal fight against the pipeline isn't against Energy Transfer. It's against the US Army Corps of Engineers. That's the federal agency that's in charge of [00:03:00] granting permission for the pipeline to pass through federal land, including under the Missouri River. It was the Army Corps that the tribe first sued back in July 2016, right before the Standing Rock protest really kicked off.

Back then, they were trying to get the federal government to require a deeper review of the pipeline route. Fast forward to today, the tribe's legal fight to stop the pipeline is still going on. It wasn't until Trump came into office in 2017, as the Standing Rock protests were already winding down, that the Army Corps did grant permission to drill under the river.

But after the pipeline was already installed, a judge took back that permission and said that the project does require a deeper environmental review. Eight years after the oil started flowing, that review, an environmental impact statement, still isn't finished. The pipeline operates with no official permission from the Army Corps and the Standing Rock Sioux tribe is sick of it.

The Army Corps of [00:04:00] Engineers also runs a series of dams along the river. Dams Standing Rock and other indigenous nations never wanted. So this new lawsuit Doug is helping prepare, it's not just gonna focus on the pipeline, but rather on multiple environmental justice issues that this nation has been putting up with for decades.

Pulling up behind us is a whole team of emergency managers from the tribal government as well as an elected member of the tribal council, and a reporter from a local newspaper.

Boat passengers: Yeah. Hey guys! Patch everybody in.

Doug Crow Ghost: Okay...

Alleen Brown: Doug briefs us on the plan. Since it's too shallow for the pontoon here, we're gonna head to the next closest option for launching a boat, which is 20 minutes away at Fort Rice.

Doug Crow Ghost: Two things are gonna happen there. One, we're gonna, it's gonna be up. The water's gonna be good. We're gonna get in the boat and we're gonna go to DAPL site, or we get down there and it's just like this. It's unusable, and we document that as [00:05:00] well. All right. Load up then you guys. Thank you.

Alleen Brown: You know, in all these years covering the Standing Rock movement, I've never actually gotten out on the water. But I have no idea as we turn onto the highway that I'm about to get even more intimate with the Big Muddy than I'd bargained for. This season of Drilled, we bring you SLAPP'd, the story of an Indigenous nation fighting for its water, an environmental nonprofit facing extinction, and an energy giant using the courts to punish protestors. I'm Alleen Brown.

The draft of Energy Transfer's environmental impact statement for the Dakota Access Pipeline was released about a year and a half ago, and it describes the company's version of what would happen if the pipeline breaks. [00:06:00] It says that within 13 minutes of a leak, Energy Transfer would shut down the pipeline.

Their boats into the river from a dock like we just visited, and they'd isolate the spill with containment booms. Skimmers, absorbent material, and vacuum suction would collect the oil. If the water was too low to launch a boat, Energy Transfer would use cranes to lower watercraft into the Missouri, and they say they have airboats on hand. But Doug and other Standing Rock leaders don't buy it. For one, the report was written by a company with ties to the oil and gas industry, he tells me about it as we drive to the next closest boat dock.

Doug Crow Ghost: [scoffs] we told him that's a conflict of interest!

Alleen Brown: Making matters worse, large sections of the emergency plans and the spill response report are blacked out. Redacted. Standing Rock leaders say they have no ability to check the work of Energy Transfer and the Army Corps.

Doug Crow Ghost: How can you really comment on something you can't see? And this is what we always said. [00:07:00] Where's the transparency?

Alleen Brown: A final decision on the easement-- the permission to drill under the river-- is expected in the next year. The writing is on the wall with Donald Trump about to become president. The Army Corps will likely grant it.

The Standing Rock Sioux tribe decided they weren't gonna sit around and wait before filing a new lawsuit.

Doug Crow Ghost: Anyway, ask me more questions.

Alleen Brown: Okay. I can do that.

Doug Crow Ghost: Come on Alleen.

Alleen Brown: As we drive. I'm noticing the way the sun is struggling to pierce through a kind of fog.

Uh, do you think this haze is, uh, from the wildfires?

Seriously, this is a serious question.

Doug Crow Ghost: Oh, oh yeah, it is. Um,

Alleen Brown: North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum declared a state of emergency a week ago. High temperatures, dry conditions, and wind are creating the perfect conditions for wildfires. Earlier in the week when I was visiting here, I'd driven by fields scorched by wildfire.

The fire had meandered through agricultural land and jumped the road. The blackened areas had the unsettling appearance of [00:08:00] an oil spill. The climate impacts of burning oil were a key issue in the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline, and here in North Dakota, it isn't hard to see how the climate crisis is impacting everyday life.

Doug takes a turn on Boat Dock Road. His team didn't use to use this dock too often, but with the water levels being so low, that's changed.

Alleen on tape: When did it start becoming an issue?

Doug Crow Ghost: Oh, it's 10 years. At least. 10 years, every year. Usually around this time, and then springtime, it'll flood, and then wintertime, it'll, it'll go low. And it just depends on the runoff. A lot of times too, of Montana's, uh, headwaters. Mm. If they had a good winter and a and a nice runoff, would there have be more luck getting into the water here though? Oh my God, yes.

Alleen Brown: The headwaters of the Missouri River are in Montana. In 2017, universities in the state did a study on [00:09:00] how climate change is impacting the river.

The researchers found that not only has Montana's snow pack in the mountains declined, the snow that does accumulate is melting earlier in the year. By late summer, there's less water than there used to be. That means more drought. Over the next century, what we're seeing today is expected to get worse. A deciding factor for how bad the droughts and fires will get is how many fossil fuels continue to be extracted, transported, and burned.

It's products like the oil carried by the Dakota Access Pipeline that are making the climate crisis worse.

Doug Crow Ghost: Let's go check it out, kids. Let's see if we're gonna go pick the big one today.

Alleen on tape: Now, I don't know if I need this giant jacket

Alleen Brown: I debate leaving my coat in the car. It's October in North Dakota, but the temperature is climbing above [00:10:00] 80 degrees.

Don Holmstrom climbs out of the backseat and heads down the ramp toward the dock. Don is the former director of the US Chemical Safety and Hazard Boards Western Regional Office. Now he works as a safety consultant for Standing Rock. He pulls out a sonar depth finder device and it says it's deep enough for us to launch.

While some of the crew sets up the pontoon, I chat with Harold Tiger and Erika Porter, who are emergency managers.

Alleen on tape: I'm curious to hear more about the wildfire.

Harold Tiger: From the reports I received, it was caused by a combiner that was combining in the field. It caught fire.

Alleen Brown: It turns out, they responded to that fire I saw.

They tell me this is the time of the year when farmers harvest hay. All it took to spark the fire was a combiner hitting a rock.

Erika Porter: We closed down the road while that fire skipped over Highway 63. The smoke was so bad that it was [00:11:00] hard to see through the smoke going across that highway.

Alleen on tape: I guess, how unusual is this? How unusual is a wildfire like that?

Erika Porter: We call it curveball climate.

Harold Tiger: Well, and and it has a drastic effect on our people. I mean, things are not happening normally at certain times of the year, so we need to start looking at that, looking outside of the box to get better prepared for those things.

Alleen Brown: The climate crisis is often called a threat multiplier. The oil in the pipeline stands to make the climate crisis worse, and also the climate crisis stands to make the impact of any oil spill worse. And there's one more piece to this puzzle that we'll get to in a second: The Missouri River dams.

We climb onto the pontoon.

Doug Crow Ghost: Ready?

Get it. Okay, let's go. Thank you, there

Alleen Brown: We putter into the little bay that leads to the river. For a second, it seems like our journey might end before [00:12:00] it's begun.

Erika Porter: Are we getting stuck?

Alleen Brown: We aren't... yet. Erika cranks up the pontoon jams.

Erika Porter: There's that pontoon song!

Alleen Brown: Don drops the depth finder into the glassy water as we troll south through a basin that's wider than a football field. Doug drives carefully navigating the braided channels that cut pathways through muddy sand bars. The constant fluctuations of the river mean the curves of the channels are unpredictable.

The stretch of the river that borders Standing Rock is called Lake Oahe. It's a reservoir that was created in the early 1960s. The Upper Missouri River today is actually divided up by a series of dams. That's because in the 1940s, the U.S. created a program called the Pick Sloan Plan. That plan is the origin story of the Standing Rock Nation's poisoned [00:13:00] relationship with the Army Corps of Engineers.

The Corps wanted to build a series of dams to control the Missouri River. The dams were meant to ease flooding, provide power and irrigation, and also make it easier for boats to transport people and products. The thing is, the Indigenous nations along the river didn't want the dams. The US government built them anyway.

They flooded and destroyed entire communities, drowning grave sites, as well as sources of food and income. People from Standing Rock say they were never adequately compensated, though it's not clear that any price could have made the dams worth what was lost.

Avis Red Bear: And it wiped all that out. It wiped away out our cherry trees, our plum trees, our, you know, it was a hunting grounds. And so they, this, this Army Corps of Engineers, when they flooded our lands, they wiped out a way of life, you know?

Alleen Brown: Avis Red Bear was born just after the dam flooded the land, [00:14:00] but she grew up hearing about what happened. And as far as Doug is concerned, the injustice of the dams is ongoing. The climate crisis may be helping create drought conditions, but it doesn't explain how quickly the water level is going up and down.

Alleen on tape: Um, yeah. So what's the deal? So the.. obviously the dam, the water is low. Why would they, why would it be low right now? Why is it low right now?

Doug Crow Ghost: Because they're trying to keep the level of the, of the Missouri River, at average, at an average, uh, level down in Kansas and Missouri for, for navigation for barges,

Avis Red Bear: so their ships can get in the water.

Doug Crow Ghost: Yep. Yep.

Alleen Brown: The Army Corps controls the release of water from reservoir to reservoir. They're attempting to balance a tangle of different needs as they do this, from preventing flooding to protecting endangered species, to letting people fish, to making sure companies can transport products. In Doug's view, the Army Corps [00:15:00] prioritizes the commercial needs of people outside the bounds of the reservation.

Lake Oahe ends up stuck in a constant state of flux.

Doug Crow Ghost: So I call our Lake Oahe the bastard reservoir of the, um, Pick Sloan Act. And it is, and you've seen it today. Today is a, you know what you guys, I am so glad you guys came today. Avis, uh, Don, because you guys are seeing firsthand what I have to go through almost on a weekly basis when we go out to do sampling on the river, we can't get out there.

Alleen Brown: When Doug and the other Standing Rock members on the boat today, think about the threats to the water, it's about not just the pipeline, but also the dam.

Avis Red Bear: So, I mean, it's just, it's so unjust, but I just love this. It's so beautiful. I'm so glad we came out.

Alleen on tape: I know. Me too. It's so beautiful.

Alleen Brown: The Army Corps denied my request for an interview. A spokesperson told me that the Army Corps operates the reservoir system according to the [00:16:00] law with guidance from a master water control manual. The spokesperson said water levels fluctuate seasonally based on precipitation, runoff, and multiple congressionally authorized purposes, including flood control, navigation, water supply, recreation, and fish and wildlife. These operations are system-wide and are not managed for any single user or economic interest.

There's another thing influencing Standing Rock's lawsuit strategy: The Greenpeace case. In its original conspiracy lawsuit, Energy Transfer claimed that Greenpeace committed defamation by saying that the pipeline would poison the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's water.

They also said its defamation to say the pipeline would catastrophically alter the climate.

Threats to their water and to the climate are two of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's key arguments against the pipeline. Energy Transfer's suit was [00:17:00] suggesting these threats don't exist.

And if you're gonna make claims like that in a lawsuit, then you have to prove it. Energy Transfer would have to hand over internal documents proving how safe the pipeline really was.

But they argued that sharing so many documents was too much of a hassle. To avoid having to turn them over, they dropped the claims about water and climate safety. But Greenpeace did not drop their request for documents. And as they continued to fight about it, some documents ended up bubbling to the surface that weren't supposed to. A report that was supposed to remain confidential appeared on a court website for anyone to download. An engineering firm called Exponent had prepared this report. It was co-written by a former Exxon engineer. Greenpeace had commissioned it as part of its legal defense. And it described something the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe had never heard about before.

It said that there had been problems when Energy Transfer's drilling contractor Michels was drilling under Lake [00:18:00] Oahe.

Doug brings the pontoon to a stop.

Doug Crow Ghost: So basically we're at ground zero and where there would be a pipeline break,

Alleen Brown: That means we're floating above the Dakota Access Pipeline. It's buried 95 feet below the lake bed.

Doug explains what the Exponent report revealed. He takes us back to January, 2017 when Energy Transfer set up two huge drills on either side of the river.

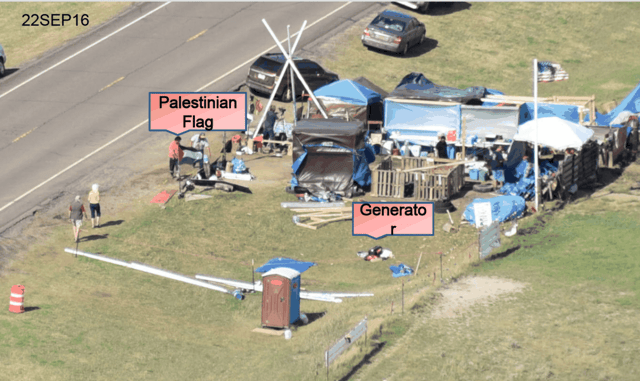

Doug Crow Ghost: At the same time, we had a camp on the other side of that cliff over there where people from around the world were protesting to stop it. And these guys over here were saying, gear it up, let's get it done.

Alleen Brown: The two drills, tungsten carbide teeth cut and ground the rock and soil under the river into fragments, each guiding a drill pipe behind it. The drill pad had been transformed to [00:19:00] resemble a military base.

Doug Crow Ghost: If you guys remember seeing pictures, they had a berm around a drill pad. They had these huge, um, it looked like Kuwait.

They had armed 24 7 guards. They had these big floodlights

Alleen Brown: Over the course of a week, the two drills chewed away pilot holes underneath either side of the river until they met in the middle the day after Valentine's Day. As they traveled thick mud was pumped at high pressure from the shore. Through the drill pipes and out the nozzles at the drill bits at the end.

Doug Crow Ghost: And they use fluid, the, the lube up, the, the sediment, and the rock, and it's just going, going and going.

The drilling mud was made of bentonite clay and water, along with some unknown chemical additives. Oil companies usually describe drilling mud as being non-toxic. But at times it has been found to include harmful pollutants. And it can hurt delicate ecosystems. The drilling mud carried away [00:20:00] the fragmented earth.

That mud and earth was supposed to flow back to the shore into an excavated pit, but some of it never did. The amount of drilling mud that disappeared was enough to fill two Olympic sized swimming pools, 1.4 million gallons. All that drilling mud had apparently oozed into the surrounding environment.

Avis Red Bear: What does it contaminate, what does that mean to our water intake? I mean, I got those kind of questions

Doug Crow Ghost: and so they don't know if it's still in or if it's underneath the water or if it's down or went down river. We didn't, they don't know nothing.

Don Holmstrom: The report didn't say,

Doug Crow Ghost: The report didn't say so.

Alleen Brown: It's unclear what happened to all of that mud. Exponent wrote that there's no indication Energy Transfer's contractors did any water testing. Doug and the tribe are concerned that there could have been something poisonous mixed into the mud that disappeared under the river, which is a big problem because again, [00:21:00] this is the Standing Rock. Sioux Tribe's drinking water source.

An Energy Transfer has had issues with drilling mud before. The company was building pipelines in Pennsylvania and Ohio around the same time it was building DAPL in North Dakota. In Pennsylvania, thousands of gallons of drilling mud leaked into wetlands. The company didn't report it to state regulators who found out that some of the mud contained unapproved additives. It even polluted tap water and caused sinkholes.

The company's subsidiary, Sunoco, pleaded no contest to 14 criminal counts related to those drilling mud spills. In Ohio, 2 million gallons of drilling mud leaked into a wetland, and state regulators discovered that some of it was laced with diesel.

Don Holmstrom: And they weren't told about that by Energy Transfer and their contractors, and so obviously they were pretty mad about it.

Alleen Brown: This is Don Holmstrom, the [00:22:00] consultant who used to work at the Chemical Safety Board. Energy Transfer got in pretty big trouble for its drilling mud spills. The US Environmental Protection Agency proposed in 2022 that the company be banned from any contracts with the federal government. The decision was never finalized, but it meant that Energy Transfer was kept out of federal contracts until earlier this year.

Don has a plane to catch and it's time to head back.

Doug Crow Ghost: Uh, great. If you guys got any other questions as we go, just ask Don. Okay. Let's, let's maneuver back to the uh, port, see if we can dock. Titanic. Alright, let's go. Thank you. I need somebody to look out in the front for, uh, icebergs. No kidding. All. Pull it out.

We the Titanic.

Avis Red Bear: Sidebar side sandbars here.

Alleen Brown: As we motor back the way we came, I think about what I'd researched before this trip. The draft environmental impact [00:23:00] statement from the Army Corps says there's only about a one in 1000 chance that the Dakota Access Pipeline will spill under the Missouri River in a given year.

But as for the entire length of the pipeline, the Dakota Access Pipeline has already leaked 13 times since an entered operation in 2017. The largest leak was nearly 200 gallons. The draft environmental impact statement says that spill risk is inherent to pipelines. You can mitigate it, but you can't eliminate it.

Then there's the climate crisis. Scientists say that if we have any hope of avoiding catastrophic climate impacts, we cannot build new fossil fuel infrastructure. According to climate scientists math, as long as the oil flows, the water is not protected.

In the pontoon, we're chatting idly about the upcoming election. As we motor back.

Don Holmstrom: I've developed a [00:24:00] healthy skepticism. Yeah. About what even people that you end up voting for because maybe they're the lesser of the, of the, the problem.

Alleen Brown: The pontoon stalls. We're stuck.

Doug Crow Ghost: Um, I don't know about your mate. I need a rescue.

No, this is all sandbar.

Erika Porter: Yep. Every bit of it.

Don Holmstrom: Can you back up?

Doug Crow Ghost: Thought we were gonna be able to go through right there.

Avis Red Bear: I'll lead.

Alleen on tape: It's the same on this side. Yeah.

Don Holmstrom: Back up?

Alleen Brown: The deep channel has turned unexpectedly into a sandbar on either side of us.

Don Holmstrom: I don't think we can go forward.

Erika Porter: Yeah. So

Alleen Brown: The boat is lodged in the muck of the river. Four of our crew jump into push.

Doug Crow Ghost: Yeah. Okay. Let me know when you guys are ready.

Alleen Brown: Doug gets ready to rev the motor.

Erika Porter: You [00:25:00] ready, Doug?

Doug Crow Ghost: Yep. Let me know when you hold on.

Erika Porter: Let's go.

Doug Crow Ghost: Ready m go.

Alleen Brown: They're pushing, but this thing is not moving.

Doug Crow Ghost: Is it even budging??

Erika Porter: Push like this. Push like this guys.

Alleen Brown: It's not looking good

Erika Porter: Lean into it.

Don Holmstrom: Starting to move a little bit.

Erika Porter: Okay. Hold Doug. Hold, hold, hold.

Alleen Brown: And here. Dear Listener, the audio cuts out because the time had come for your host to get intimate with the Missouri River. I roll up my pants to my knees and jump in. Now there are six of us pushing and with the mud of the Missouri River oozing between my toes, I begin to see the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's point.

How quickly could a crew really [00:26:00] navigate these channels in an oil spill emergency? And how much lower will this river drop as the climate crisis deepens?

We push again. The pontoon inches a few feet forward, but it's still stuck. We keep pushing. It springs forward.

Doug Crow Ghost: Nothing happened. We're good.

Avis Red Bear: Nothing happened at all!

Alleen on tape: It was nice to meet you.

Don Holmstrom: Yeah, great to meet you. Have safe travels.

Alleen on tape: Yeah, you too.

Alleen Brown: Doug and Don consider the trip a success. We'd unintentionally illustrated their point. Three days later, the tribe files its lawsuit on Indigenous People's Day.

Months later, in the courtroom, in the winter of 2025, the things we grappled with on the water come up in court. Energy Transfer wants Greenpeace to pay them back for delaying the start date of the pipeline's commercial [00:27:00] operations. They say that the pipeline was supposed to be pumping oil by January, 2017, but didn't start operating until June, and that cost them $80 million.

But Greenpeace is arguing that what actually prevented Energy Transfer from finishing the project is that they didn't have the Army Corps permission to drill under the Missouri River. They didn't have the easement. Greenpeace wasn't stopping the oil from pumping, a federal agency was standing in the way.

If Greenpeace was solely responsible for the easement delay, then that means that the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and its lawsuit and its calls to action, the money it poured into the pipeline fight had no hand in the Army Corps decision. The theory of the lawsuit doesn't match with what happened, and removes the Indigenous nation from the story entirely.

Energy Transfer [00:28:00] is also saying that it was Greenpeace's divestment campaign that forced Energy Transfer to delay its loan refinancing by about two years. They say that the delay was because Greenpeace spread lies about Energy Transfer. The alleged lies were meant to convince banks to divest from the pipeline.

And Energy Transfer wants the environmental nonprofit to pay them nearly a hundred million dollars for this. Except that Energy Transfer's own records conflict with this story. The pipeline company took careful notes when their board met, and several sets of board meeting minutes say that Energy Transfer decided to hold off on refinancing, not because of anything about Greenpeace, but because the Standing Rock Sioux tribe was in the middle of their legal battle with the Army Corps, and the banks wanted to wait and see what would happen.

Once again, Energy Transfer's story of Standing Rock erases the role of the Standing Rock Sioux [00:29:00] tribe. I call up Doug, the tribe's water guy, about what's happening with the lawsuit. He wasn't too impressed with the $55,000 that Energy Transfer says Greenpeace put into the movement or the $90,000 that they say Greenpeace's former executive director fundraised.

Doug Crow Ghost: I'm like, what are they suin' em for? They didn't do any, what did they do?

Alleen Brown: He tells me the tribe took in $11.7 million in donations from people who wanted to support the pipeline resistance camps and the legal fight. He knows the number because he managed the budget.

Doug Crow Ghost: We paid over $60,000 just for porta-potties.

Alleen Brown: That's right. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe spent more on toilets for a couple months than Greenpeace allegedly donated throughout the entire movement. The money came via the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's crowdfunding pages, but also an envelope sent directly to the tribal office.

Doug Crow Ghost: Envelopes of, uh, you know, $50 [00:30:00] envelopes with cash or checks in them for $25, whether they donated $5 or $500,000. Um, they all got a thank you letter from the chairman with our IEN number and their tax break number. So we did that to, I want to say, 20,000 people.

Alleen Brown: To Doug, the arguments in this lawsuit just don't make sense.

Doug Crow Ghost: Well, I'd say this is all a bunch of bullshit, and I could tell you that nothing ever happened with Greenpeace.

They didn't do shit. They don't have the right to sit here and even talk about DAPL and definitely Energy Transfer doesn't. You got, you know, and I would say this is all just a, a ploy to try to find a scapegoat.

Alleen Brown: Greenpeace wants to talk about that leak drilling mud in court, but Judge Gion says they're not allowed to.

Energy Transfer didn't answer my questions about the report. [00:31:00] During his testimony, the project manager Mike Futch said there were no problems with the drilling. But a regulator at the North Dakota Department of Environmental Quality told the North Dakota Monitor that he was aware of some issues with drilling mud.

The regulator just didn't think it was a big deal. "This is something we see happening virtually on every horizontal boring we see," he said. There's a world where the Dakota access pipelines, oil and drilling mud spills are considered normal and acceptable, but decades of experience have shown the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe that neither the state of North Dakota nor the US Army Corps of Engineers nor Energy Transfer are authorities they can trust.

And honestly, the tribe was not so sure they could trust Greenpeace either. Because there was a moment last year when Greenpeace was offered an opportunity to avoid all of this. One that meant throwing the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe under [00:32:00] the bus. That's next time on Drilled.