By Danielle Mackey and Fernando Silva. Jennifer Ávila also contributed reporting to this piece, which was reported in collaboration with Contracorriente. Photos by Fernando Destephen, courtesy Contracorriente.

Honduran environmentalist Juan López had a priestly calm. His steady gaze and his way of speaking, polite but direct, were notable whether he was philosophizing with friends or leading a protest. Although he knew well the threats associated with fighting for the environment in Honduras, he was vocal about the fact that he had no intention of becoming a martyr.

López was recognized internationally for his work to protect the water and territory of Guapinol, a community in the Bajo Agúan valley. For more than a decade, Guapinol’s environment and social fabric have been threatened by an iron ore mine, Inversiones Los Pinares, owned by Lenir Pérez, one of Honduras’ most powerful businessmen. López, who was also a municipal alderman and was active in his local Catholic Church, helped lead the movement to stop the mine and was branded a criminal in the process.

On a Saturday evening in mid-September, López became the sixth environmentalist killed while defending Guapinol since 2019. As he left church, a masked man on a motorcycle rolled up, raised a gun, and assassinated him. It bore the hallmarks of a hired hit.

On October 4, the Honduran police and public prosecutor announced that they had arrested López’s alleged assassin and two accomplices, but they emphasized that they are still working to identify the intellectual author of the crime. Community members have demanded an impartial investigation. They have reason for concern: So far, no one has been prosecuted for the wave of killings of Guapinol land defenders.

Immediately after López’s murder, the Municipal Committee for the Defense of Common and Public Goods (Comité Municipal de Defensa de los Bienes Comunes y Públicos de Tocoa), a local environmentalist group of which López was a member, pointed out two men whose interests López’s activism had challenged: businessman Lenir Pérez, and Adán Fúnez, the mayor of Tocoa, the municipality where the village of Guapinol is located.

Just a few days before he was killed, López publicly demanded that Mayor Fúnez step down after journalists with Insight Crime published a video confirming the mayor’s ties to organized crime. In undercover footage that shook the nation, the mayor and the brother-in-law of Honduran president Xiomara Castro were caught meeting with members of a drug cartel called the Cachiros to negotiate bribes for Castro’s 2013 campaign as well as for her husband, former Honduran president Manuel “Mel” Zelaya. Fúnez responded to the video by denying ever receiving the money, and President Castro condemned “any type of negotiation between drug traffickers and politicians.” Fúnez has also denied any part in López’s death. He did not respond to a request for comment for this story, nor did Zelaya.

Environmentalist Juan López being laid to rest in the cemetery at Tocoa, Colón, surrounded by those who knew him and shared his struggles. September 2024. Foto CC / Fernando Destephen.

There is no evidence of direct connections between businessman Pérez and the cartel, but Fúnez has been a strong ally of Pérez, and since 2021, the Honduran Public Ministry has been investigating the mayor for falsifying municipal records on behalf of Pérez’s mine. Pérez, sought through his lawyer, Erick Spears, did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Ten days after López’s death, the Honduran Public Ministry issued formal charges against Pérez and twelve other people affiliated with Los Pinares and its pelletizing plant, for environmental crimes including the illegal exploitation of natural resources. Some of the accused were immediately arrested in Honduras, but Pérez has been living in the U.S.

In response to questions from Drilled and Contracorriente, Public Ministry spokesperson Yuri Mora indicated that Honduras will request his extradition. "When the Public Ministry accuses someone who isn't in the country, solicitations or legal requests are always sought so that the person is returned and faces justice," Mora wrote in a text message.

Repression at the hands of a blurry conglomerate of economic and political interests is familiar to environmentalists throughout Honduras – and Latin America more generally. More land defenders are murdered in Latin America than any other region in the world, according to the organization Global Witness – and Honduras is consistently among the top five countries. In 2023, the country had the highest number of such killings per capita, according to the organization’s annual report. It is often difficult for communities or investigators to determine exactly who is behind the aggressions, creating an atmosphere of impunity that appears to protect the powerful.

In the case of Guapinol, even the fact that the mine was a co-investment with North Carolina-based Nucor Corporation, one of the largest steel companies in the world, remained unknown by the public until recently.

Although Nucor has publicly stated that it ceased its ownership and decision-making stake in the project five years ago, new records unearthed by Drilled and Contracorriente indicate that the steel giant retained financial ties to the mining company as of late last year. Nucor did not respond to requests for comment.

The Guapinol defenders are aware of the formidable web that their environmentalism threatens. They’ve faced violent repression since long before López’s assassination, going back to the arrival of the Los Pinares mine.

The Fight for the Guapinol River

The Guapinol River twists through the green expanse of hills and valleys in northern Honduras until it reaches the rural community that shares its name. Under the cool shadow of overhanging trees, women wash clothes in the gently flowing water and children splash about. The only hint of the harrowing battle the neighbors have fought over the past decade to keep the river alive is a boulder painted white with words in blue, stating, “No a las mineras,” or “No to Mines.”

The roots of the fight extend to around 2011, when the Honduran government proclaimed that nearly 250,000 acres of forests would become a protected national park, safeguarding the 34 rivers that rely on the area. The park was then baptized with the name Carlos Escaleras, an environmentalist killed 15 years earlier after opposing a planned African palm-oil processing plant owned by Pérez’s late father-in-law, Miguel Facussé, one of the wealthiest men in Central America.

In April 2013, Pérez and his wife, Ana Facussé, requested permission to explore a 536-acre plot inside the park for iron oxide. Pérez could only proceed legally if congress redrew the park’s boundaries – which legislators did remarkably quickly, by that December.

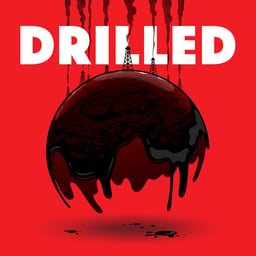

In response to the company’s successive tramplings of norms meant to regulate the industry, environmentalists in and around Guapinol formed the Municipal Committee for the Defense of Common and Public Goods. They signed petitions, demonstrated outside city hall and set up a protest camp to block construction. On October 27, 2018, more than 1000 police and soldiers violently evicted the camp. One environmentalist was killed and various were injured. Two soldiers were also killed.

A Comité Municipal de Defensa de los Bienes Comunes y Públicos (CMDBCP) protest against a thermoelectric project in Tocoa, December 2023. Foto CC / Fernando Destephen.

Before long, the local police and prosecutor accused 31 of the environmentalists, including López and two brothers named Reynaldo and Aly Domínguez, of being an organized crime syndicate called “The Anti-Miners.” López was alleged to be the ringleader. As has happened in the U.S. and other nations, legal structures designed to dismantle organized crime were repurposed to silence environmentalists: The prosecutor turned to a court that was supposed to target drug cartels.

After voluntarily presenting themselves to the authorities in February 2019, eight of the accused spent two and a half years in pre-trial detention, on charges including illicit association and robbery. “Our only crime is defending that national park,” said Municipal Committee member Juana Zúñiga of the detentions.

In February 2022, the Honduran Supreme Court vacated the charges, finding that they had violated due process from the beginning, and the defenders were released. But five days after López’s murder, a Honduran appeals court ruled that it would reconsider the vacated charges against five of the environmentalists, including López – suggesting that even death won’t stop the criminalization.

A Steel Giant’s Ties

A few minutes’ drive from the river, we met with Guapinol residents in February 2023 under the tin roof of an open-air community center to hear about their fight against Los Pinares and Pérez.

Reynaldo Domínguez described how, a month prior, unknown assailants had ambushed and killed his brother Aly and another environmentalist, Jairo Bonilla, as they returned from work. The community understood their murders, like two others over the past several years, as a message to silence the movement.

After we left, drones circled for over an hour above the homes of Domínguez and Juana Zúñiga, who had coordinated our visit. They were accustomed to harrassment like this. They knew it was punishment for having spoken to journalists, and a threat: we’ve got you in our sights. But who owned the drones, they couldn’t say with any certainty.

The next day, on the streets of downtown Tocoa, López held a microphone in front of a crowd of farmworkers and called for an end to the violence in the surrounding valley. Behind him, teenagers held cloth banners bearing the names of their families’ agricultural cooperatives. Grandmothers in ball-caps held the hands of children as they marched, flanked by dozens of young men on motorbikes, who revved their engines until the ground shook. It was an impressive display of farmworker force, led by López.

Four months later, another brother of Reynaldo Domínguez, Oquelí, was shot to death by strangers in his family home. His entire extended family, 44 people who had been born and raised in Guapinol, hastily sold their cattle and land for a fraction of their worth and scattered to live clandestinely in other parts of Honduras and abroad..

Domínguez has little faith that the culprits will be brought to justice without extraordinary efforts by land defenders and the international community.

Over the past decade of the mine’s development, Pérez, the project’s public face, had seemingly endless cash and direct access to the highest echelons of the Honduran government. His clout only made sense later, when it came out that the Los Pinares mine and the nearby pelletizing plant were a joint venture with Nucor. The presence of the multinational had not been publicly known in Honduras, because the partners had channeled their project through Panama-based firms, on whose boards of directors Pérez and various Nucor executives sat.

When Contracorriente revealed the relationship in 2020, together with the Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística and Univision, Nucor responded that it had left the ownership of the project in October 2019 and no longer held “influence in the direction of the company.” But newly unearthed Honduran public records suggest Nucor was still entangled in the controversial mining project as recently as late last year.

Los Pinares’ annual statements indicate that, at least until September 30, 2023, Nucor and Los Pinares maintained outstanding accounts receivable and payable between one another. As of December 31, 2022, according to income statements, Nucor owed the Honduran company 6,448,571 lempiras, or about $262,000. The Honduran company in turn owed Nucor a long-term debt of 860,923,000 lempiras, or around $34.7 million. The following year, the values of both the accounts payable and receivable between the companies increased. The last annual statement in the Los Pinares file indicates that, by September 2023, Nucor's debt to the Honduran company had risen by about $11,000, to 6,706,134 lempiras. Meanwhile, Los Pinares' debt to Nucor increased about $60,000, to 862,466,500 lempiras.

The annual statements do not say what the companies were paying each other for. However, according to an accountant familiar with large financial transactions in Honduras, who asked not to be identified for fear of reprisals, such long-term debts could involve anything from loans to the purchase of raw materials.

Given the repressive and murky landscape, public officials say it is important to know whether Nucor retains connections to the mine. “The ongoing tension in Guapinol serves as a stark reminder of the urgent need for more rigorous due diligence and accountability in international investment and development financing,” said Jan Schakowsky, a U.S. congressperson who has spearheaded congressional action on Guapinol.

A Labyrinth of Moneyed Interests

Throughout the mining fight, Pérez’s business empire has boomed. Under a corporate umbrella called the EMCO group, it expanded into Guatemala, Panama, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Delaware and Florida. The Honduran government contracted Pérez to build a new international airport. In El Salvador, he donated $1 million to Nayib Bukele’s first presidential campaign, and after Bukele won, Pérez received a multi-million dollar contract to build a new cargo terminal for El Salvador’s international airport.

But then, on April 28 of last year, the FBI raided a sprawling $10 million equestrian compound in Palm Beach, Florida, that Pérez had recently purchased. Pérez’s lawyer claimed the FBI wasn’t targeting Pérez but Nucor, offering no additional information. The FBI told Drilled and Contracorriente that it “neither confirms nor denies the existence of an investigation and declines to comment further.”

In August 2023, a group of 20 members of the U.S. Congress wrote to Secretary of State Antony Blinken, calling for a “definitive cancellation of the Los Pinares mining licenses” and investigations into the killings. They noted that the FBI raid of Pérez’s Palm Beach hacienda was “apparently in relation to an investigation into Nucor,” adding that “it is strongly suspected [that Nucor] retains interests in Los Pinares.”

The question of who is behind the various types of repression that Guapinol faces remains elusive. As the revelations about Mayor Fúnez show, Nucor and Pérez are far from the only profiteers in the region.

The U.S. government long suspected Pérez’s late father-in-law, Miguel Facussé, of using his vast plantations, which are near Guapinol, as drug transport zones, where boats and planes might offload their illicit cargo into waiting vehicles. A labyrinth of cartels and smaller armed paramilitary and criminal bands exists in the region, working both for themselves and for various masters. The Honduran police and military have also repeatedly repressed farmworkers, apparently sometimes on behalf of the private sector.

A spokesperson for the largest corporation founded by Facussé, Dinant, said the company “and its owners have never been involved in any activities related to drug trafficking or any other type of illegal activity. We strongly condemn, and make every effort to prevent, the use of any of our property to carry out illegal activities.” Armed Forces spokesperson Captain Mario Rivera told Drilled and Contracorriente that the military presence in the region is for combating drug trafficking and protecting citizens. The Honduran national police did not respond to a request for comment.

The presence of so many groups determined to forge fortunes on the land, and the justice system’s habit of failing to hold murderers to account, makes violence against Guapinol’s anti-mining movement easy – a problem that, unfortunately, is widespread in Honduras. “It is very difficult to identify who is behind the physical attacks against Honduran defenders,” said anti-corruption lawyer Ruth López, of the human rights organization Cristosal. Many companies, both local and foreign, that operate in the country are “unscrupulous” and abusive, she said.

The pelletizing plant associated with the Los Pinares mine. Foto CC/Fernando Destephen.

An Uncertain Prohibition

Last February, a group of eighty Honduran congresspeople made a surprising move, restoring the Carlos Escaleras National Park to its original outline. This should prohibit new or renewed mining concessions in the park.

But the situation for the people of Guapinol remains complicated, according to the legal representative of the Municipal Committee, Rita Romero. “The company has a lot of iron oxide that it extracted while its concession contract was in force,” said Romero. In January of last year, Los Pinares announced that it was going to export about 800,000 tons of pelletized iron oxide valued at $190 million. It did not identify the buyers.

Romero stressed that, although mining at Los Pinares should now cease, it’s unclear if authorities will enforce the prohibition. The Honduran environmental secretariat did not respond to a request for comment.

For now, the cycle of abuses against Guapinol environmentalists remains unbroken. Four years before his assassination, Juan López spoke soberly about the stakes of their struggle. “Mining companies are always going to cause extreme levels of violence, wherever they go,” he told Contracorriente. “They crush the dignity and bodies of local inhabitants, because their goal is to extract wealth from nature, over and over again.”

“As long as you keep your mouth shut and only say good things about development, everything is fine,” he said. “But as soon as you raise questions, you can expect immediate and violent reactions.”

Since the murders of his brothers, Domínguez has lived in hiding, far from home. He pointed out that displacement is exactly what the environmentalists of Guapinol have been resisting. “To me, the struggle that my brothers undertook, so we wouldn’t have to leave the community where we were born, is an act of valor,” he said. He wonders how much longer his community will have to fight.

Danielle Mackey works in both U.S. and Central American media. She is currently based in New York, on staff at The New Yorker, after living mostly in El Salvador from 2008 until 2021 as a freelance investigative, longform reporter. She still writes as an independent journalist, and she sits on the editorial board of Contracorriente.

Fernando Silva is an investigative journalist. His work focuses on covering corruption, power structures, extractivism, forced displacement and migration. He is also an audiovisual producer and has worked for half a decade in this field with organizations that defend human rights and development institutions in the country. In 2019 he graduated from the Investigative Journalism Course at Columbia University and that same year was part of Transnacionales de la Fe, which in 2020 won the Ortega y Gasset prize for best investigative journalism awarded by the Spanish newspaper El País.

Contracorriente is an online media platform that supports in-depth and investigative journalism in transmedia formats, in Honduras and throughout Central America.