This is part three of a seven-part series produced in partnership with Grist as a companion to the SLAPP’d season of the Drilled podcast. You can see all seven pieces together in a beautiful layout over on Grist’s site, where you’ll also find other great climate stories.

Greenpeace was founded just as the contemporary environmental movement was taking off in the 1970s. What set the organization apart from others at the time was dramatic protest actions at sea: Greenpeace activists zoomed little boats in between whaling ships and harpoons, risking their lives to save whales. From the very beginning, Greenpeace was ardently opposed to any kind of violence. Still, governments and companies began to label its activities as ecoterrorism.

“I don't think there's any credible examples of anything remotely like something you could describe as ecoterrorism in Greenpeace's history,” said Frank Zelko, a historian at the University of Hawai‘i who wrote a book on the organization called Make It a Green Peace!. “Unless you reframe ecoterrorism as a bunch of people just blocking bulldozers or hanging a banner between a couple of chimneys.”

It’s important to note that Greenpeace’s efforts to save wildlife at times took aim at Indigenous peoples and practices. For example, an anti-seal-hunting campaign Greenpeace launched in the 1970s destroyed subsistence living for a number of Indigenous communities and a major income stream for many Indigenous nations. By the 1990s, activities like those began to get pushback.

“We challenged the white organizations back in the early 1990s with environmental racism,” said Tom Goldtooth of the Indigenous Environmental Network. “Greenpeace stepped up.”

In 2017, when the RICO lawsuit hit Greenpeace, Goldtooth was in touch with the organization again. “We said: ‘Hey man, this is mucked up. We’ll stand with you. You’re going to fight this.’” But by 2024, as the lawsuit looked like it would go to trial, it became less and less clear that Greenpeace actually would fight Energy Transfer.

Management for Greenpeace in the U.S. assessed that they had a 5 percent chance of winning. If this went to trial, they determined that Greenpeace as they knew it might cease to exist.

Then, around the winter of 2024, Gibson, Dunn, & Crutcher reached out to Greenpeace with a settlement proposal: Energy Transfer would drop the lawsuit if the organization put out a statement. Greenpeace would have to indicate that there was violence during the Standing Rock movement, that the pipeline did not pass through the Standing Rock Sioux’s land, and that the company did not deliberately destroy sacred sites. In other words, they’d have to refute the statements that Energy Transfer had claimed as defamation.

The statement Energy Transfer wanted Greenpeace to make “would have been a lie,” Goldtooth said.

Over the next few months, Greenpeace leadership deliberated over the settlement offer. A worst-case trial scenario could mean the loss of a 50-year legacy and could scuttle Greenpeace’s future impact. It could put up to 135 staff members out of work and risk dismantling the organization's global network. It could cause reputational damage to the Standing Rock Sioux, allies, and other activists who would be forced to testify, and it could set a legal precedent for suing movement organizations out of existence. The best-case trial scenario: Greenpeace would lose, but would be able to say that it went down fighting. Some in the organization concluded that this trial scenario would be catastrophic.

A worst-case settlement, on the other hand, didn’t seem quite as bad to some. It could cause a public relations crisis, and Greenpeace might lose a few million dollars a year in funding. Some staff might resign, and Indigenous peoples and nations might stop working with the organization. The statements that Greenpeace would have to sign could also be used by Energy Transfer to go after the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. But Greenpeace would live to fight another day.

Managing the worst-case scenario of a settlement became the option Ebony Twilley Martin, Greenpeace’s newly appointed executive director, and several senior managers supported.

However, the view was not shared by everyone, and the question of the settlement began to divide the organization.

Multiple people high up in the organization strongly opposed Energy Transfer’s settlement proposal. For example, Deepa Padmanabha resigned as deputy general counsel because she disagreed with senior management’s position on the settlement, according to sources close to Greenpeace. Staff members who got wind of the possibility of settlement organized a letter to the board, expressing their own concerns. Meanwhile, Twilley Martin met with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe about the possibility of settling.

“It would've hurt us, no doubt,” current Standing Rock Chairwoman Janet Alkire said of the settlement. “ We'd have to fight against that too. Again, lies. It's not true.” However, she said she viewed the decision as Greenpeace’s to make.

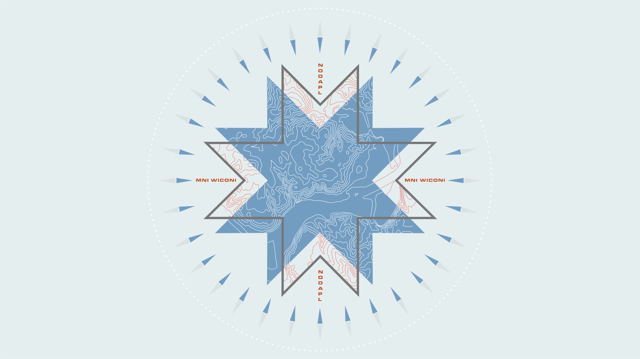

Tom Goldtooth also spoke with Twilley Martin on the phone multiple times. He said he knew she was under a lot of pressure, but he was clear in his conversations with her about what it would mean for Greenpeace to accept Energy Transfer’s terms. “This would end our relationship with you, with Greenpeace,” he said he told her. “It was that serious. This is a life and death issue to our Indigenous peoples. This is a life and death issue to life itself, to water, to the river.”

Goldtooth said that Twilley Martin was quiet. “I feel it hit her hard.”

Ultimately, it was up to Greenpeace’s board to decide. “It was clear for us that it was a hell no,” recalled Niria Alicia Garcia, a Greenpeace Inc. board member. To Garcia, the survival of Greenpeace was not the most important thing on the line, but she said it made sense to her that certain people did want to accept the settlement.

“When you’re an eight-figure, big legacy, big green, you are going to have to hire people who know how to keep a 501(c)(3) viable and afloat,” she said, referring to nonprofit organizations that are tax-exempt under Section 501(c)(3). “And at the same time, you’re going to need to hire people who are fully aligned and ready to embody the mission. That is the forever tension in nonprofits that exist to be in service to the movement.”

In the spring of 2024, the board voted to reject the settlement proposal. It came at a cost: Ebony Twilley Martin, the first Black woman to serve as Greenpeace’s executive director, hailed as a “historic first” in the environmental movement, left the organization. Padmanabha ultimately rejoined the U.S. organizations as senior legal adviser.

A spokesperson for Greenpeace in the U.S., Madison Carter, wrote in a statement: “Difficult conversations are a common byproduct of risk assessment exercises, and this case is no different.” She added: “SLAPP lawsuits like the one we are facing from Energy Transfer are intended to divide movements and drain resources, which is why it is paramount that we remain as prepared as possible for any and all outcomes.”

Twilley Martin declined to comment.

Garcia, the Greenpeace board member, said, “I’m proud that we stuck to our values and decided to stay true to the spirit and the mission and the purpose of why Greenpeace ever came to exist.” She added, “At the end of the day, nonprofits are discardable; they are revocable; they are replaceable — and the movement is not. Relationships are not.”

North Dakota’s Morton County District Court set a date for trial: February 24, 2025.

You can find the rest of the stories in this series, the podcast and other related stories here.