This is part six of a seven-part series produced in partnership with Grist as a companion to the SLAPP’d season of the Drilled podcast. You can see all seven pieces together in a beautiful layout over on Grist’s site, where you’ll also find other great climate stories. You can also find the rest of the stories in this series, the podcast, and related stories here.

Up until October 2023, Energy Transfer claimed that Greenpeace also committed defamation when it said the pipeline would poison the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s water and that the pipeline would catastrophically alter the climate. In order to prove those claims, Energy Transfer would have to turn over internal documents to show how safe the pipeline really was.

However, the company sought to avoid handing over the pipeline safety records and dropped the claims. But Greenpeace didn’t drop its requests for the files — and as they continued to fight about it, some documents became public record.

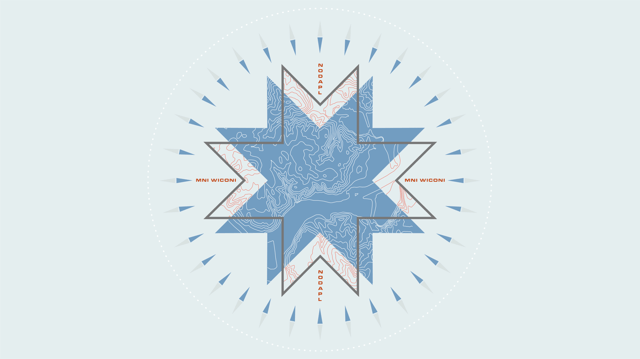

A report commissioned by Greenpeace, based on field reports and completed in January 2024, found that Energy Transfer’s contractors allowed 1.4 million gallons of drilling mud to disappear into the hole they bored under the riverbed. Drilling mud is a clay and water mixture combined with chemical additives, used to lubricate a drill and carry away fragmented earth. Oil companies usually describe drilling mud as non-toxic, but at times it has been found to include harmful pollutants, and it can hurt delicate ecosystems. The authors, from an engineering firm called Exponent, found that the drilling mud was supposed to flow back out of the tunnel and onto the shore to be stored in an excavated pit. But some of it never did. Enough drilling mud to fill two Olympic-sized swimming pools disappeared into the environment.

Energy Transfer has gotten in trouble in the past for using unapproved additives in its drilling mud. During pipeline construction in Pennsylvania, the company leaked thousands of gallons of drilling mud into wetlands, creating sinkholes and polluting tap water. Energy Transfer’s subsidiary Sunoco pleaded no contest to 14 criminal counts related to the spills. In Ohio, the same year the Dakota Access pipeline was completed, Energy Transfer leaked another 2 million gallons of drilling mud into the environment as it built a different pipeline — some was laced with diesel.

The spill described in the Exponent report was news to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, despite its years of raising questions and concerns about pipeline safety. So in October 2024, when the tribe filed its latest lawsuit against the Army Corps, the lawyers cited the drilling mud report as one of many reasons that the pipeline should finally be shut down. Standing Rock’s lawsuit was dismissed in March, although the tribe has appealed.

Energy Transfer alleged that Greenpeace committed defamation by accusing the company of deliberately destroying sacred sites. At the heart of that claim is the word “deliberate” and whether or not, on September 3, 2016, the company intended to destroy the sites. Court documents, public records, and testimony at trial paint a hazy picture of just how those sites were handled.

Tim Mentz’s survey began by Tuesday, August 30, and lasted through Thursday, September 1. That same week, Energy Transfer emailed police to inform them that their construction crew was moving east toward the river, according to a record displayed during the trial. Because of the company’s concerns about protests, sharing construction information with police was a routine practice at the time. The company’s schedule, which it outlined in an email, suggested that the bulldozers wouldn’t arrive in the area with the sacred sites until after September 8.

On September 2, 2016, after Mentz identified the sites, Mike Futch, the project manager for the North Dakota section of the Dakota Access pipeline, sent out his construction manager and a security guy to investigate. "We concluded that the features that Mr. Mentz had identified were outside the limits of the disturbance that we had planned,” Futch said on the stand.

According to Futch, construction crews were able to avoid any stones on the edge of the right-of-way. That analysis, Futch said, allowed him to sidestep calling in the company’s archaeology specialists. The company saw no reason to call the Standing Rock Sioux, either.

Energy Transfer’s bulldozers arrived at the site the next morning — Saturday, September 3, on Labor Day weekend — more than six days earlier than what it had indicated in the schedule sent to police days before. Public records obtained from the Morton County Sheriff’s Office confirm that that morning, the company moved its bulldozers at least 15 miles east to the area that Mentz had been working in.

That the bulldozers were moved out of order on a holiday weekend is a key reason the tribe and water protectors believe that Energy Transfer deliberately destroyed the sites. So exactly when Energy Transfer decided to bulldoze the area matters.

“Yes, we did advance and do some out of sequence work,” Futch told the court. Not because of the sacred sites, he said, but only to get ahead of a powwow planned for the area: The crews wanted to be out of way before new people arrived on top of the protesters already present.

Futch said several law enforcement officers, including the deputy incident commander working under Morton County Sheriff Kyle Kirchmeier, were notified of the change in plans. But when Kirchmeier testified, he said he was unaware the bulldozers would be in that area. Normally, he added, he was notified of construction plans, but not this time.

The dog handlers were surprised, too, according to police reports obtained from the sheriff’s office. The owner of Frost Kennels, Bob Frost, told police that Energy Transfer had asked the company to bring the dogs out around mid-September when a ruling in Standing Rock’s lawsuit against the Army Corps was expected. The security workers anticipated that the dogs would be patrolling a fence around a construction site, and one worker said he thought they'd be joined by two police officers per dog handler. Instead, Bob Frost found out in the middle of Friday night, only hours after Earthjustice filed the coordinates, that they needed to show up with dogs the next morning at 10 a.m.

While Energy Transfer’s defamation claim focused on the word “deliberate,” the company has also disputed that there were any sacred sites at risk at all. “Apparently a guy named Mentz came up with a story,” the former Energy Transfer Vice President Joey Mahmoud said in an email at the time.

In court, Gibson Dunn lawyers and the company’s witnesses pointed to a report from the chief archaeologist of the North Dakota State Historic Preservation Office, Paul Picha, who concluded that “no cultural material was observed in the expected corridor. No human bone or other evidence of burials was recorded in the inventoried corridor."

Picha was deposed by lawyers, but the interview wasn’t shown in court. He said that his assessment didn’t actually mean much about the truth of Mentz’s claims.

“So if the North Dakota State Historic Preservation Society says something isn’t a cultural site, that doesn’t mean it isn’t a cultural site to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, correct?” asked one of the lawyers.

“Yes,” Picha replied.

Energy Transfer’s own archaeology contractor, Gray & Pape, concluded in a separate report, obtained via a public records request, that four of Mentz’s sites were in the path of the pipeline. The archaeologist, Jason Kovacs, reported that those four stones didn’t show signs of being archaeological sites and that there was no ground disturbance there — although one of the stones was covered in dirt.

However, Kovacs clarified what he meant when he was deposed for trial. He told lawyers, "I’m not qualified to assess what is cultural property or not," and he confirmed that the company had no Indigenous specialists on staff.

"The vast majority of the times, we have no access to the tribal perspective,” said Kovacs. “My assessment of an archaeological site has to be on the archaeology itself, and that’s where I leave it. It may have further significance, but that’s, you know, not archaeological."

His testimony was never aired for the jury.

Energy Transfer’s lawyers presented what appeared to be its key evidence that Greenpeace International defamed the corporation. In November 2016, an organization called BankTrack asked banks to divest from the Dakota Access pipeline, noting that the company’s personnel deliberately desecrated documented burial grounds and other important cultural sites. The letter was signed by 500 organizations, including Greenpeace International.

“Does Greenpeace International stand by that?” Trey Cox asked Mads Christenson, Greenpeace International’s executive director.

“We believed that to be true at the time, and we still do,” Christensen replied.

“Wouldn’t you have to talk to Energy Transfer to understand their state of mind?” asked Cox.

“Our understanding was very clear from the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and allies that a number of concerns about sacred sites had been pointed out that were later desecrated and destroyed.”

Christensen added, “If you’re aware of the fact and still go ahead, then it must be deliberate.”

You’ll find the rest of the stories in this series, as well as the podcast and related stories here.