If there is a Holy Land for nuclear energy, Australian Shadow Climate Change and Energy Minister, Ted O’Brien, seems to think it's Ontario, Canada. Other countries have well-established nuclear power industries, of course. There’s the United Kingdom where the Hinkley Point C nuclear reactor – dubbed “the world’s most expensive power plant” – where work began in 2007 with an expected start date of 2027 but is now at least ten years behind schedule and billions over budget. Meanwhile, it’s sister project, Sizewell C, is estimated to cost the equivalent of AUD $80bn (GBP £40bn, USD $49bn). There’s France where, in mid-August 2022, half the country’s nuclear reactors were forced offline, many as a direct result of climate impacts such as heat and drought. Over in the United States, storied home of the Manhattan Project, where newly minted energy secretary (and fracking CEO) Chris Wright has announced a commitment to “unleash” commercial nuclear energy, one of the last two new nuclear power builds attempted this century forced Westinghouse into bankruptcy protection, and a separate effort by NuScale to build a cutting edge small modular reactor (SMR) was cancelled in November 2023 due to rising costs. There’s also Finland, a country of 5.6 million people, that finally turned on Europe’s newest nuclear reactor 18 years after construction began, finishing up with a price tag three times its budget. Though it had a noticeably positive effect on prices after start up, the cost of building Olkiluoto-3 was so high, its developer had to be bailed out by the French government. Since then, technical faults continue to send the reactor temporarily offline – a remarkably common occurrence among nuclear reactors.

Ontario, however, is so far the only place in the world that has ripped out wind turbines and built reactors – though the AfD in Germany has pledged to do the same if elected, and US President Donald Trump has already moved to stop new windfarm construction. Thanks to much self-promotion by pro-nuclear activists and Canada’s resources sector, that move caught the imagination of O’Brien and Australia’s conservative party. Now, as Australians head to polls in 2025, the country’s conservatives are looking to claw back government from the incumbent Labor Party with a pro-nuclear power play that critics charge is nothing more than a climate-delay tactic meant to protect the status quo and keep fossil fuels burning. “This is your diversion tactic,” says Dave Sweeney, anti-nuclear campaigner with the Australian Conservation Foundation. “There’s a small group that have long held an ambition for an atomic Australia, from first shovel to last waste barrel to nuclear missile. Some of the people who support this are true believers, for others it’s just the perfect smoke screen for the continuation of coal and embedding gas as a future energy strategy.”

Apples and Maple Syrup

On the face of it, Ontario is an odd part of the world on which to model Australia’s energy future. Privatization in both places has evolved messy, complicated energy grids, but that’s about all they have in common. One is a province on the sprawling North American landmass, and the other is a nation that spans a continent. Ontario has half the population of Australia and spends five months a year under ice. Its energy system has traditionally relied on hydro power and nuclear, where Australia is famously the driest inhabited continent on the planet that used to depend on coal but now boasts nearly 40% renewable electricity as of 2024. One Australian state, South Australia, already draws more than 70% of its power from renewables and frequently records weeks where all its electricity needs are met with solar and wind. Unlike Ontario, and the rest of Canada, Australia has no nuclear industry aside from a single research reactor in the Sydney suburbs. The cost of transmitting power over vast distances in Australia makes up approximately two-fifths of retail power prices. Electricity prices in Ontario, meanwhile, have been artificially lowered by an $7.3bn a year bundle of subsidies for households and businesses. Comparing the two jurisdictions is stranger than comparing apples and oranges; it’s more like comparing apples and maple syrup.

None of this has stopped the province from becoming O’Brien’s touchstone for the marvels of nuclear energy, and “Ontario” from becoming his one-word reply to critics who question the wisdom of creating a new nuclear industry from scratch in Australia. If the country wanted to transition away from coal, the Coalition’s suggestion was it should be embracing nuclear energy — not more renewables — just look at Ontario. “We have to keep learning the lessons from overseas," O’Brien told Sky News in August 2024. “There’s a reason why countries like Canada, in particular the province of Ontario, has such cheap electricity. They’ve done this many years ago. They were very coal-reliant and eventually, as they retired those plants, they went into nuclear.”

Weirder still, O’Brien is not the only Australian political leader to be chugging the maple syrup. Ever since the conservative Liberal-National Coalition began to float the idea of an atomic Australia as part of their 2025 election pitch, its leader, Peter Dutton, has similarly pointed to the Canadian province as an example for Australia to follow. In interview after interview, Dutton referred to Ontario’s power prices to suggest that nuclear is the future for Australia – raising the question: how did Ontario capture the hearts and minds of Australia’s conservatives?

Atomic Australia

The idea of an atomic Australia has long lived in the heart of Australian conservatism. Former conservative Prime Minister Robert Menzies once begged the United Kingdom to supply Australia with nuclear weapons after World War II, going so far as to allow the British to nuke the desert and the local Indigenous people at a site known as Maralinga. The first suggestion for a civilian nuclear power industry evolved out of this defense program and has never been forgotten. Iron ore magnate Lang Hancock and his daughter, Gina Rinehart, today Australia’s richest woman, both remained fascinated by nuclear energy. In 1977, Hancock, a passionate supporter of conservative and libertarian causes, brought nuclear physicist Edward Teller to Australia on a speaking tour to promote nuclear power, including an address to the National Press Club where he promised thorium reactors would change the world.

Though Australian plans to build a domestic nuclear industry have failed due to eye-watering costs and public concerns about safety, the country today is the fourth largest exporter of uranium according to the World Nuclear Association, sending 4820 tonnes offshore in 2022 and providing 8% of the world’s supply. The country is also planning to acquire a nuclear-powered submarine fleet through AUKUS, an alliance with the US and UK. This increasingly tenuous defense deal is thought unlikely to happen thanks to issues with US and UK shipyards, but the existence of the program has been used to justify the creation of a civilian nuclear power sector. There have been at least eight inquiries or investigations into the viability of a nuclear industry in Australia since 2005, and five proposals to build government-owned nuclear waste dumps since 1990. Each inquiry has concluded that nuclear power would largely be a waste of time and money and, with the exception of two facilities in Western Australia that store low-level radioactive waste, efforts to build additional dumps capable of storing higher grades of waste have mostly foundered for lack of community support. This time around, with the current push to embrace nuclear energy, the federal Australian Coalition’s ideas appear to be shaped by the internet, where a pro-nuclear media ecosystem of influencers and podcasters has flourished just as nuclear has become attractive to conservative parties worldwide.

When Australia LNP opposition leader Peter Dutton formally unveiled the gist of his “coal-to-nuclear” transition plan in June 2024, for example, he was asked what the plan would be to handle the waste and responded with a curious sleight of hand: “If you look at a 470MW [nuclear] reactor, it produces waste equivalent to the size of a can of Coke each year.” A fact check published in the Nine papers pointed out that nuclear reactors typically operate on much larger scales than 470 megawatts. Citing World Nuclear Association figures, it found a typical large-scale nuclear reactor with 1-gigawatt capacity will generate 30 tonnes of spent fuel each year – roughly 10 cubic metres, or 10,000 litres a year. It is unclear where Dutton or his speechwriters stumbled onto this talking point, but it appeared to be a corruption of the idea that one person’s lifetime waste from nuclear energy could fit inside a soda can – a common Facebook meme promoted by the Canadian Nuclear Association. A similar claim was repeated last year in a social media video by Brazilian model and Instagram influencer Isabelle Boemeke.

Boemeke, who goes by the online persona Isodope and claims to be the “world’s first nuclear energy influencer," begins her video by outlining her daily diet, starting with black coffee and ending with a post-gym snack of energy-dense gummy bears. In a dramatic transition, she then compares the size of a gummy bear to the size of a uranium pellet, before launching into a didactic explanation of the role these pellets play in generating nuclear power.

“It also means the waste it creates is tiny. If I were to get all of my life’s energy from nuclear, my waste would fit inside of a soda can,” she says, before ending by advising her viewers not to drink soda because “it’s bad for you."

Neither the Canadian Nuclear Association nor Boemeke elaborated on how the world might dispose of the cumulative waste if a significant proportion of the Earth’s population drew their energy from nuclear power – but then that is not the point.

Boemeke is hardly alone. Online there is a small but determined band of highly networked, pro-nuclear advocates, podcasters and social media influencers working to present an alternate vision for an atomic world. Many of those involved in this information ecosystem are motivated by genuine belief or concern over environmental issues, even if their activities often align with right-wing causes and ideas. Nuclear is often positioned as an essential climate solution, as well, although it's typically a cynical promise: nuclear reactors take decades and billions of dollars to build, buying fossil power more time. In the U.S. especially, pro-fossil conservative politicians often use nuclear as a rhetorical wedge: they will ask any expert or advocate in favor of climate policy whether they support nuclear and imply that if they don't, they must not be serious about actually addressing the climate crisis by any means necessary.

One of those helping export the strategy from North America to Australia is Canadian pro-nuclear advocate, Chris Keefer, host of the Decouple podcast and the founder of Canadians for Nuclear Energy. A self-described “climate hawk”, Keefer is a practicing emergency physician in Toronto who built an online presence as an advocate for keeping existing nuclear power plants open. Through his public advocacy, he has been instrumental in cultivating the image of Canadian – and particularly Ontarian – nuclear excellence, a legend he has recently promoted in Australia through a series of meetings, speeches and his podcast.

Nuclear on Tour

According to Keefer, his first encounter with the man who may become Australia’s next Climate Change and Energy Minister took place in early 2023. A group including Ted O’Brien traveled from Australia to the United States and Canada on a nuclear “fact finding” trip. On the itinerary were meetings with center-left and center-right think tanks, energy policy advisors, technology companies, independent advisory services, utility companies, energy ministers and Keefer. Since then, Keefer says, he and O’Brien have “run into each other” at events where they have had “brief informal conversations”.

One such event was in September 2023, when Keefer traveled to Australia to give a keynote address at Minerals Week, hosted by the Minerals Council of Australia (MCA) at Parliament House in Canberra. Ahead of his visit, a write up published in the The Australian Financial Review framed Keefer as a “leftie” and “long time campaigner on human rights and reversing climate change” who had previously “unthinkingly accepted long-standing left-wing arguments against nuclear” but had embraced nuclear due to his unionism. During his time in Australia, Keefer says he met with federal Opposition leader Peter Dutton to discuss “Ontario’s coal phaseout and just transition for coal workers”, Labor MP Dan Repacholi who represents the coal fields of the Hunter Valley, a senior staffer from Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen’s office, and the Australian Workers Union.

Like an evergreen in the desert, the shift in context made the Canadian’s appearance in the seat of Australian power a curiosity. Asked about whether he knew of the MCA’s historical activities on issues such as land rights, labor relations and climate change, Keefer said he had no “detailed understanding” and that he was just happy to speak to “anyone who will listen” about nuclear – a common framing by pro-nuclear advocates. His speech, “How Ontario Decarbonised”, was scheduled before a lunch session with federal Opposition leader Peter Dutton and told how Ontario arranged a “truly just transition for Ontario coal workers”. The pivotal moment, according to Keefer, was Ontario’s 2018 provincial election. The contest represented a fork in the road on energy policy that Keefer framed as a “referendum on The Green Energy Act,” a bill introduced in 2009 that sought to massively expand renewable energy production in the province. The result delivered a thundering win for Ontario’s Progressive Conservative Party.

“The center-left Ontario Liberal Party suffered a humiliating defeat, going from a majority in parliament to losing their official party status and dropping to only seven seats,” Keefer said.

As political folklore this was a tale that would have appealed deeply to Keefer’s audience, whose constituencies were threatened by renewable energy projects. The MCA itself has historically been hostile to Indigenous land rights and campaigned heavily to stop or delay any government response to climate change during the 90s, largely in defence of coal producers. The association again mobilised in 2009, spending AUD$22m to kill a proposed mining tax and bring down the incumbent Labor government in the process, ushering in a decade-long conservative government. To the Coalition members in the audience, Keefer’s story represented hope. The party has been losing ground to climate-conscious independent candidates in recent years, particularly in the wake of the Black Summer Bushfires and the devastating Northern Rivers floods. The promise of an Ontario-style “blue-blue alliance” – a political alignment between certain blue-collar unions and conservatives – would be alluring, especially given how well a pro-nuclear campaign paired with anti-wind scaremongering. Even a nuclear-curious Labor member may have spotted a way to stem the flow of votes to Greens.

Changing Winds

What Keefer presented to the Australian resources sector as a glorious triumph, Don Ross, 70, recalls as a difficult time in his small community that became a flashpoint in a fight over Ontario’s future. When he and his partner Heather first moved to Prince Edward County, an island in Lake Ontario, his neighbors in Ottawa described the tiny rural community as an isolated backwater. Upon arrival, they found the total opposite: a home with people who were warm, kind and generous. The year was 1980 and in those that followed, the idyllic setting began to attract money. With time, vineyards were planted, art galleries opened and restaurants began to cater to the newcomers. So much money eventually rolled into Prince Edward County, that the people with money began working to preserve their favorite rustic retreat exactly as is – and that meant stopping the wind turbines. Today the population sits around 26,000 people, at least until the snowbirds fly south for the winter. Then the population drops with the mercury, even as the winters are getting shorter. It still gets cold – it’s 12C below zero at this time in early January – but the snow isn’t falling like it used to.

“Winter is about two months long instead of four. We get lake snow. Snow doesn’t stay, it comes, then it’s gone in a couple of days. We’ve still noticed a huge change in just our lifetime,” Ross says.

As a longtime member of the County Sustainability Group, Ross says an awareness that the climate is changing pushed him and others to fight for the White Pines Wind development back in 2018. In his telling, the community had the best wind resource in the area and had been pitched as a site for development since the year 2000. There were six or seven serious efforts over the years, all small projects in the range of 20 megawatts that would have allowed the community to be largely self-reliant in terms of power. Only White Pines came closest to completion. It was a ten year development process that Ross says was fought at every step by an anti-wind campaign, with some of the campaigners active since 2001.

“They just took all the information from Australia or America or around the world to fight the same fight – they used the same information, same tactics, played on the same fears and uncertainties,” Ross says. “They were very effective. They had the media backing them, and the conservatives saw an opportunity to drive a wedge.”

Don and Heather Ross in front of turbines near their home. Photo courtesy Don Ross.

By that point the incumbent centrist Liberal government, having wiped out the previous conservative government, was flagging after almost 15-years in power, and Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives were sensing blood. The feeling was that Ford, the brother of former Toronto mayor, the late Robert Ford, would do or say almost anything to take office – and he did. During one campaign Town Hall event, Ford – who turned cultivating outrage as a public relations strategy into an artform – accused the wind developers of corruption and the governing Liberal Party of “forcing its ideology down the backs of small-town conservatives” with all this green, renewable energy.

“I’m dead against these turbines,” he told one woman named Sandy. “This is just a big scam. These things are just a big scam.”

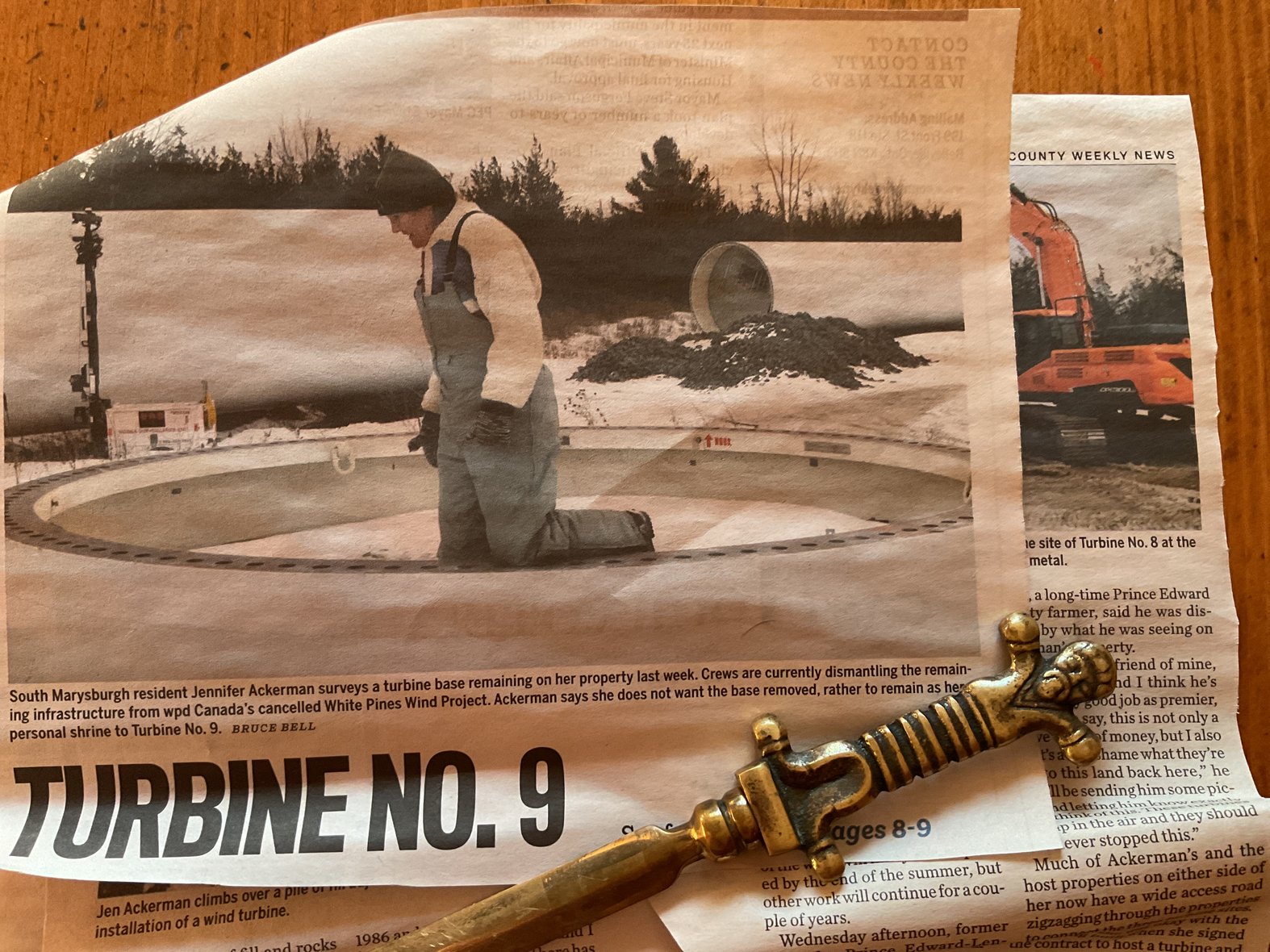

By election day, four of the nine towers at the White Pines windfarm development were already built, the cranes were on site, and the other towers were laying in position ready to go. The development was just four weeks from completion when the election was called for Ford.

On his first day in office, Ford cancelled 758 renewable energy contracts. These were not industrial-scale power generation. Most were small, community-scale projects that had been supported by the previous government. The White Pines wind farm outside Milford was the last significant wind development yet to be finished and firmly within the new government’s sights.

Ontario’s future Energy Minister, Todd Smith – a former radio presenter who has since left politics and now serves as Vice President of Marketing and Business Development at the Canadian nuclear technology firm, Candu Energy, a subsidiary of AtkinsRealis – had opposed White Pines from its inception. If Smith wanted it gone, he would get his way. The Ford government passed legislation, the White Pines Wind Project Termination Act, to kill the project. Its provisions stopped the developers from suing the government but outlined a formula for compensation. Ross and members of the County Sustainability Group tried to protest the decision. They pulled together a 19,360 signature petition to save the wind farm and presented it to the provincial parliament in Toronto. As Ross recalls, the new administration wasn’t interested in what they had to say and the turbines came down.

“None of us thought that would happen,” Ross says. “None of us actually thought for a second they would tear down a windfarm that was so close to being done.”

“Even the people who don’t really care one way or another couldn’t believe it happened. Why would they do that? They spent all this energy, all this money, to put these things in the ground, spent more money and more fossil energy to take it out of the ground. For what? Nothing.”

News clipping of Jen Ackerman on top of the foundation of a demolished wind turbine. Photo courtesy Don Ross.

Next the Ford government slammed the brakes on renewables investment. It shredded a cap-and-trade program that was driving investment in the province, a successful energy efficiency strategy that was working to reduce demand and a deal to buy low-cost hydropower from neighbouring Quebec. During the campaign, Ford promised Ontario’s voters that taxpayers wouldn’t be on the hook for the cost of literally ripping the turbines out of the ground and ending the other 750 or so projects. He had pledged that doing so would actually save CAD $790 million. When the final tally came in, that decision alone ended up costing taxpayers at least CAD $231 million to compensate those who had contracts with the province. The amount finally paid to the German-company behind the White Pines development is unknown. The former developers remain bound by a non-disclosure clause.

Canada’s Nuclear Heartland

At heart, the fight in Ontario was over power prices. Those on the political right charged that renewable energy was responsible for driving up the cost of power, but others, like Professor Mark Winfield from York University, point to an electricity system that had been badly managed over decades. “It was insane,” says Professor Winfield. “If you break down what was driving the capital costs in the whole system, nuclear was still the number one driver, but the way the narratives played out, renewables got blamed.”

Under Ford, Ontario – and later, Canada itself – fell into a nuclear embrace. Much of this, Professor Winfield says, played on a historical amnesia and nostalgia for what was considered a hero industry that traced its origins to the dawn of the atomic era. The province supplied the refined uranium used in the Manhattan Project and its civilian nuclear industry grew out of the wartime program. At first, the long-term strategy was to use domestic nuclear power as a base for a new export industry, selling reactor technology and technical expertise to the world. Development on a Canadian-designed and built reactor, the heavy-water CANDU – short for “Canadian Deuterium Uranium” – began in 1954. Two sites, Pickering and, later, Darlington were set aside for the construction of nuclear plants. The first commercial CANDU reactor would start up at Pickering in 1971 but the hope of a nuclear-export industry died on the back of questions about risk, waste, cost and scandals involving Atomic Energy of Canada that included attempts to sell CANDU reactors to Nicholai Ceausescu’s Romania.

“Even by the mid-seventies, there were very serious questions about cost overruns and all kinds of other things that ultimately led to a Royal Commission,” Winfield says.

That Royal Commission raised questions about the planning model underpinning Ontario Hydro, the government-owned power company responsible for the nuclear build out. The company operated on a “build it and they would come” approach with little oversight and ended up building 20 nuclear reactors. The last at Darlington was completed in 1993. By 1997, Winfield says, Ontario Hydro was $38bn in debt.

“It was essentially bankrupt mostly because of the nuclear construction program,” Winfield says. “It had to strand $21bn in debt on taxpayers and ratepayers, mostly nuclear-related, to render the successor corporation, Ontario Power Generation, economically viable.”

“So Ontario went from an electricity system that was basically almost 100% hydroelectric to a system that was about 60% nuclear by the early 90s. By 1997, eight of the original 20 reactors in Ontario were out of service.”

To compensate, the province began to rely more heavily on coal-fired power for electricity, leading to bad air quality and a public health crisis. Through the nineties there were occasional suggestions to start the nuclear build once again, but Winfield says by 2009 the combination of cost and weak demand meant they went nowhere.

Until 2018, the idea of a nuclear revival in Ontario seemed a fantasy. Then Doug Ford began ripping out wind turbines and blocking the province from considering renewables as part of its energy mix. It was an act designed to play to his base, especially the workforce within the nuclear industry. According to the Power Workers’ Union, Ontario’s nuclear industry employs 60,000 people. A much older count carried out in 2002 put direct employment from the province’s reactors at approximately 11,700 people. Whatever the precise figure is today, the weight of numbers from those directly involved, or further out in the supply chain, offered a constituency that could be appealed to. It also helped that Ford’s government was able to run its energy systems largely by executive fiat. The previous government, Winfield says, had poorly designed policy frameworks to facilitate the rollout of renewable energy and overpaid for the electricity wind and solar generated. The same government passed legislation in 2016 that resulted in Ontario’s electricity system being run through ministerial directive, bypassing external agencies that would normally review costs or test options.

More of the Same

So far, Ford’s government – re-elected in 2022 – has taken advantage of this opaque arrangement to pursue its plan to refurbish 10 existing nuclear reactors, build four new 1200 megawatt units at the Bruce Nuclear Facility, and four new small-modular reactors (SMR) at Darlington – the centerpiece of Ontario’s promised nuclear revival. Until recently, SMRs have been held up by advocates and industry as the hardware of the future, though in serious nuclear circles attention has increasingly been turning to massive, gigawatt-scale reactors such as the Westinghouse AP1000 and the Korean APR1400.

In many ways this is more of the same. Traditional nuclear reactors have typically been designed to chase scale for viability. The result has been big, bespoke plants that are made-to-order, with equally large price tags starting around USD$10bn. That price, however, almost always goes up with every delay, engineering complication and the decades needed to complete construction. SMRs, by contrast, are intended to work in the other direction. Each unit is built to be smaller, more standardized, with fewer components or systems. On paper, this is supposed to make it possible to manufacture the units in large batches, bringing down costs, which are historically the barrier to a broader embrace of nuclear power. As the Globe and Mail reported in early December 2024, Christer Dahlgren, a GE-Hitachi executive, acknowledged as much during a talk in Helsinki in March 2019. The company, which is responsible for designing the BWRX-300 reactors – an acronym for “Boiling Water Reactor 10th generation” – to be installed at Darlington, needed to line up governments to ensure a customer base. Keeping the total capital cost for one plant under $1 billion was necessary, he said, “in order for our customer base to go up”.

The initial price for Ontario’s new reactors, however, was offered before the design had been finished. As the cost is not fixed, any change to the design at any part of the process will up the cost as the plans are reworked. Professor M.V. Ramana, a physicist with the University of British Columbia and author of the book Nuclear is Not the Solution says this is standard for the industry – and a threat to the business that needs to be constantly managed. Even with market capitalizations of tens of billions of dollars, the publicly-owned utility companies most likely to invest in nuclear power take on considerable financial risk with any given project – a risk that only goes up as the price tag climbs through the billions. At some point, this risk hits a ceiling. Credit rating firms will threaten a downgrade, forcing the project to be abandoned to stop the financial destabilization of the company. In this way the nuclear business, Professor Ramana says, depends on the sunk cost fallacy.

“If you start off with a very high cost estimate, then there's not much risk of it going up, because you’ve already padded it so much, right? But that's not what these people are doing, because they know that once you say it will cost $20 billion, the government is going to say, ‘oh, we can't afford that.’,” Ramana says.

“So the industry has to start small, tease people in, invite them into the game. And once they have put in a certain amount of money, once the ground has been dug, then you jack up the cost estimate, and they're stuck.”

SMRs were first suggested as a way to address this problem but may end up repeating the cycle. So far Ontario is the only jurisdiction to fully commit to a new SMR build. In January 2023, Ontario Power Generation, the successor entity to Ontario Hydro, signed the contract to deploy a BWRX-300, and preliminary site preparation at Darlington is currently underway. As Darlington was already an approved site for nuclear operations, the regulatory process is expected to be shorter, meaning the project will move towards construction much more quickly than others might – such as any new greenfield development in Australia. If everything goes to plan – a questionable assumption given the project will bind Ontario and Canada to United States at a time when US President Donald Trump is threatening to impose tariffs – the first reactor is expected to come online by 2028, with additional reactors to follow by 2034 and 2036.

Others have been happy to watch as no one yet knows how much this program is going to cost. With the initial sticker price advertised before the designs were actually completed, it is understood Darlington’s SMR has grown in size since it was first proposed, with a corresponding cost blowout many times the starting price expected. Some estimates, such as Professor Winfields’, put the total cost of the Ford government’s nuclear refurbishment and SMR build plan in the range of $100bn, but firm numbers on the expected cost of the SMR build and the refurbishment of existing reactors have remained elusive. Industry insiders expect the numbers to be released by the end of 2025, potentially after an early provincial election. Drilled contacted the Ontario Department of Energy to ask when information may be available on the cost of its nuclear build out but did not receive a response.

“The idea that anybody would be looking at us as a model in terms of how to approach energy and electricity and climate planning is just bizarre,” Winfield says. “You can’t make this stuff up. We’re a mess.”

“We’ve embedded enormous costs and, the other corollary here, is that our greenhouse gases from the electricity sector are going through the roof. We are on track to an almost vertical growth curve through the 2020s, as, with the province having ruled out all of the alternatives, it is having to run the gas plants to make up for supply shortfalls due to retiring and out-of-service nuclear plants.”

Ontario’s Soft Power

Winfield’s is a very different read of the landscape than the one presented by Chris Keefer, who rejects these criticisms, saying claims about overblown costs and delays are themselves overblown – a deflection that has been repeated by Australian political figures. In a written response to Winfield, Keefer presented a sunnier view of Ontario’s nuclear sector, saying the current refurbishment is going well and arguing the introduction of the Renewable Energy Cost Shift in 2021 – a subsidy introduced during the pandemic, after the election of the Ford government – represents the ills of renewable power. To support a claim that renewable energy forced up power prices in Ontario, Keefer cited analysis by The Fraser Institute, a partisan free market thinktank and partner of the global Atlas Network that has pushed climate denial for years and promoted the use of plastic bags as a health measure during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic. Asked about this, Keefer said he has no relationship with The Fraser Institute and that he relied on the report because there was no easily shareable alternative source. He said he believed it to be “a well researched, factually accurate report.”

Nuclear, in Keefer’s view, remains not just a climate solution, but the climate solution. A self-described “climate realist”, he has developed this theme across more than 300 episodes of his podcast, Decouple – much of this output devoted to specifically promoting the Canadian nuclear industry and the CANDU reactor. It is a story told again and again, whether in conversation with figures like climate contrarian and long-time nuclear advocate Michael Shellenberger and Shellenberger’s former staffer Mark Nelson, or through deep dives into subjects such as the politics of Canada’s nuclear revival, the history of CANDU reactors, and an interview with Ontario’s Energy Minister Todd Smith on “Ontario’s nuclear revival”– published months before Smith took a position as Vice President of Marketing and Business Development with Candu Energy.

Keefer knows his reach. He says he has given no formal advice to the Australian federal Coalition on nuclear but adds that his podcast “is listened to by policy makers throughout the anglosphere,” meaning that “it is possible that the thinking of Australian policy makers has been influenced by this content.” Among his lesser-known guests have been a small contingent of Australian pro-nuclear activists such as Aidan Morrison and former advisor to Ted O’Brien, James Fleay, both of whom have been publicly involved in making the case for an atomic Australia.

Keefer appearing on the news and posing with his podcast guests. Photo from his website.

As far as pro-nuclear advocates go, Morrison has self-styled himself the “bad boy of the energy debate”. A physicist who abandoned his PhD with the University of Melbourne, he worked briefly as data scientist with large banks and founded a Hunter S. Thompson-themed bar “Bat Country”. His first foray into public life and nuclear discourse was as a YouTuber, where he used the platform to attack the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) and its Integrated System Plan (ISP), a document produced from a larger, iterative and ongoing planning process that guides the direction of the National Electricity Market. From there Morrison was thrust into public conversations about nuclear energy in Australia with a series of write-ups by Claire Lehmann, founder of Quillette for The Australian. In December 2023, Morrison was hired into the Centre for Independent Studies (CIS), another free market think tank and Atlas Network partner, as head of research on energy systems. In that role, Morrison would lead a team of four with no prior experience in dealing with energy systems, telling a parliamentary inquiry in October 2024, “none of us have experience as electrical engineers in the electricity sector.” Through this time he carried on his attacks against AEMO, making technical critiques of certain assumptions and accounting methods used in the ISP that he then presented as fatal to the entire planning process.

In early January 2025, Morrison appeared to take things a step further when, in a 26-minute video posted to social media, he declared war. Filmed from an attic, he looked down the barrel of his camera to speak “to anyone who will listen”, before elaborating on what he suggested was a “dramatic and damning” conspiracy at the heart of AEMO and its ISP.

“This ship needs to be burnt to the water line and sunk, and a new one refloated probably with a new crew on board. That’s the devastating conclusion I have come to – it is just beyond salvage, beyond repair,” he said.

Morrison followed up this with two other videos that appeared to put every individual or institution responsible for planning the country’s energy systems on blast. Days after Drilled first contacted CIS for this story, Morrison posted a 40-minute video where he insisted he was “not alleging deliberate wrongdoing or conspiracy,” but called for resignations as “a direct consequence of what the ISP has plainly become.” These would be followed by two more videos in which he accused the Australian Energy Regulator of lying, and the Australian Energy Market Commission of a lack of accountability.

As Keefer hosted Morrison on his podcast, Morrison returned the favor in October 2024 when he brought Keefer back to Australia for a CIS event titled “Canada’s Nuclear Progress: Why Australia Should Pay Attention.” Leading up to the event, they toured the Loy Yang coal-fired power plant together, and visited farmers in St Arnaud, Victoria who have been campaigning against the construction of new transmission lines. Where Keefer previously presented himself as a lefty with a hard realist take on climate change, his address to the free market think tank took a different tack.

Over the course of the presentation, Keefer once more retold the story of the pivotal 2018 provincial election in Ontario, but this time elaborated on how an alliance between popular conservative movements and blue-collar unions mobilised against what he called a “devastating” renewables build out. Because “it was astonishingly difficult to convert environmentalists into being pro-nuclear”, Keefer explained how he had sought to exploit a vacuum around class politics by targeting workers unions and those employed in the industry by playing to an underlying anxiety. Nuclear power plants, after all, are complex systems that take skilled work to monitor and maintain. In an increasingly precarious economy, the stable, well-paid union jobs this offers have become precious. The prospect of winding down the plant offered a ready-made constituency receptive to the promise that nuclear power could thrive – and they along with it.

In the mix were union groups such as the Laborers International Union of North America (LiUNA), the Society of United Professionals, the boilermakers union and, critically, the Power Workers’ Union. These were all unions whose membership depended on big infrastructure builds, but it was helpful that Keefer’s advocacy aligned with the interests of capital and government. Twenty thousand signatures on a petition wasn’t enough to save the White Pines wind farm from demolition in 2018, but according to Keefer, 5874 names on an online petition to the House of Commons he organized as part of a campaign to save the Pickering nuclear plant in 2020 was enough to earn him access.

“That really opened the doors in Ottawa politically for me,” he said of the petition to save Pickering. His go-to tactic to achieve this influence, he said, was the “wedging tool” to pull left and centrist parties “kicking and screaming at least away from anti-nuclearism.” His goal was to present a “countervailing force” to environmental NGOs who he claimed had “infiltrated” the Canadian federal government. The Canadian Minister for environment and climate change Steven Guilbeault, who had once scaled the CN Tower during a protest, had “earned the moniker ‘Green Jesus’,” he lamented as he alleged Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s chief of staff and “many other key staffers in his office were former World Wildlife Fund executives.” Canada’s resource minister had gone so far as to defend a German plan to phase out nuclear following the Russian invasion of Ukraine – a stance so unthinkable, Keefer described it as “an atrocity”. Keefer then suggested this cabal of unemployed World Wildlife Fund executives led by an empowered environment minister had to be countered to re-establish the primacy of extractive industries and their interests.

“[Environmental NGOs] cultivate, through their organizations, very capable people who go on to, I think, play a behind the scenes role, at least within Canadian politics, again, staffing the office of major politicians,” Keefer said. “And I’ve learned in my lobbying efforts, the key thing is to treat the staffers with incredible respect, build those relationships, get their Whatsapp number, and the rest is history.”

“So the environmental NGOs were very, very powerful. We needed to form a countervailing force within civil society, and so with that intent I co-founded Canadians For Nuclear Energy in 2020 very quickly, to have some kind of influence.”

Asked about what he meant with his comments, Keefer said he was “not suggesting a conspiracy” and suggested that ‘infiltration’ was “a melodramatic choice of words”. He also said he did not accept financial support from the Canadian government or the nuclear industry.

“Simply put, senior members and staffers within the Trudeau government had prominent backgrounds with eNGOs with anti-nuclear positions and carried those positions with them into government,” he said.

“These individuals were a strong antinuclear pole within the Liberal government and its policy positions up until 2022 when it began to change course into a full-throated pro-nuclear government.”

A Confluence of Energies

Within this convergence of pro-nuclear activism, internationalist conservative political ambition and new media ecosystems, companies within Canada’s nuclear industry have also been positioning themselves to take advantage should the prevailing wind change in Australia. In October 2024, Quebecois engineering services and nuclear company, AtkinsRéalis – the parent company of Candu Energy that now employs Ontario’s former energy minister, Todd Smith – announced it was opening a new Sydney office to “deliver critical infrastructure for Australians”.

Though little known in Australia, the company has a storied history in Canada. Formerly known as SNC-Lavalin, the Quebecois company changed name in 2023 in the long wake of a lingering corruption scandal involving allegations of political interference by Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in the justice system. Today the company holds an exclusive license to commercialize CANDU reactor technology through Candu Energy and in 2023 signed an agreement with Ontario Power Generation to help develop Canada’s first SMR reactor. A year later, the company signed a memorandum of understanding with GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy to support the deployment of its BWRX-300 reactors in the UK.

A spokesperson for the company said no one from AtkinsRéalis or its subsidiary, Candu Energy, has “met specifically members of the Australian Federal Coalition on nuclear energy”, but the company did participate in the 2024 Australian Nuclear Association annual conference in early October to talk about how Canada’s nuclear industry works. Shadow Minister for Climate Change and Energy, Ted O’Brien spoke in the following session.

“Our approach in the nuclear sector is to engage in countries where this solution is part of the energy strategy,” an AtkinsRéalis spokesperson said. “The pursuit of nuclear energy is clearly a decision for the Australian people to make; should they decide to engage on that path, AtkinsRéalis would be ready to assist at any time with our know-how and track record to deliver these types of projects."

Under a future Coalition government, AtkinsRealis’s work with traditional reactors and SMRs would make it one among a field of contenders for lucrative contracts to design, build and operate any nuclear facility. The Federal Coalition’s current plans, however, remain vague on specifics. So far the only public details consist of a suggestion to build seven nuclear power generators in different states and territories through a state-owned entity similar to Ontario Power Generation. All the sites are the locations of former, or retiring, coal-fired power plants, two of them owned by energy giant AGL which was not consulted on the proposal or notified about the announcement on the day.

Just getting started, however, would require lifting a ban on nuclear power introduced in 1998 by former conservative prime minister John Howard, and any state-level equivalent. Communities, many of which are already concerned about unanswered questions such as how material will be transported and stored, or how much water will be required in the driest inhabited continent, would need to be consulted. The Coalition have pledged to spend two years undertaking consultation but whether or not it will respect community opposition, or seek to override it by tilting the scales, as occurred in the South Australian community of Kimba during a failed attempt to build a nuclear waste dump there, remains to be seen.

If all goes according to plan – a heroic “if” – the earliest any nuclear generator would come online in Australia is 2037 – or 2035 if the country embraces SMR technology – with the rest to follow after 2040. In the short-to-medium term, the Coalition leader Peter Dutton has freely admitted his government would continue with more of the same in a manner reminiscent of Ontario: propping up Australia’s aging fleet of coal-fired power plants, and burning more gas as a “stopgap” solution in the interim. What the party will do for renewables remains less clear, with the leader of the Nationals, the Coalition’s junior partner, suggesting an investment cap on the sector may be imposed if elected. Dylan McConnell, an energy systems expert with University of New South Wales says whether or not these “paper reactors” actually get built, the Coalition’s proposal is a time-suck that translates to more fossil fuel burned, and more carbon pollution generated.

“We’re talking gigatonnes of extra CO2. An additional thousand million tonnes. At a minimum,” McConnell says. “You’ve got the direct implications of delaying the closure of coal, the rollout of renewables, but you also have these un-discussed, un-talked about emissions from the rest of the economy.”

“This is not going to deliver anything in the times that are relevant to what the Australian system needs, or certainly what the climate needs. It’s not a serious policy or proposal.”

To sell this vision to the Australian public, the Coalition released a set of cost estimates in late December 2024, claiming its plan would be (AUD) $263bn cheaper than a renewables-only approach. These figures, however, were declared dead on arrival. Not only did the modelling underpinning them assume a smaller economy, with a vastly lower take up in electric vehicles over time, but it excluded the entire state of Western Australia – a state twice as big as Ontario and nearly four times as big as Texas with a tenth of the population – and did not consider ancillary costs such as water, transport and waste management. Even more nuanced reviews, published weeks later, found the assumptions underpinning the model outlined a program of work that would choke off renewables and backslide on Australia’s commitments under the Paris Agreement.

The party that cultivated the art of deploying economic modelling to set the terms of public debate on climate turned to economist Danny Price, founder and managing director of Frontier Economics, to run the numbers on the cost of its nuclear plan. Price - a notably cantankerous figure with what appears to be a personal grudge against AEMO - has previously taken contrarian positions on climate policy largely on economic grounds, volunteered to work for free on the Coalition’s nuclear costs. Upon the release of his second report laying out his work, the near-universal reaction from every expert canvassed was critical. A common theme was that Price’s costings were not worth the paper they were written on.

The same evening they were released, Price met the storm of criticism in a late evening interview with the ABC to defend his work, and a subsequent op-ed published in the Australian Financial Review. He claimed that, across the two reports, he had only sought to recreate AEMO’s modelling work but adapted it to include nuclear from 2036. To support his analysis, Price said he was not an expert on nuclear energy, but he had built an “extensive database” of over 650 generators constructed since the fifties and put more weight on recent data. In particular, he sought to test an “assumption” by the agency that a rapid transition to renewables was necessary or realistic.

“There’s a few sources of information that you should refer to rather than so-called ‘experts’,” Price said. “I wouldn’t even put myself in the category of a nuclear expert. Where you really need to draw your information is the International Atomic Energy Association, and places like that, and look at the experiences of all the other generators that have been built.”

Price dismissed concerns about the long-time frames of nuclear builds, saying “there’s no reason why, over a number of years, that we can’t build these facilities”, comparing the engineering challenge to Australia’s work in fossil fuel extraction.

“You can see Australia’s capability; we’ve built the same number of LNG trains in about the same years, that cost about the same on a per unit basis as a reactor and they are extraordinarily complex machines,” Price said. “No one sat there and said, look this is impossible. Australians are too stupid. They’ve all been built.”

He also waved off criticism that, under the Coalition’s plan, the country’s increasingly unreliable coal-fired power stations would need to be kept open longer, telling his interview: “Closure dates of coal-fired generators is an economic concept. You can keep a coal-fired generator running as long as you want. They’re the ultimate in grandfather’s axes; you can keep them going if you want to. It’s just a matter of the returns from doing that.”

Price did not directly address the costs associated with keeping coal plants open in his ABC interview, the increasingly frequent outages,or mention the science and pressing reality of climate change.

Power Politics

The lack of detail and apparent effort to crib from Ontario’s conservatives on strategy underscores how the politics of nuclear power is what made it attractive to the federal Coalition, a party that continues to fiercely protect the interests of oil, gas and coal producers. As the reality of climate change increasingly compels action, the party has been facing a challenge from independent, climate-conscious candidates known collectively as the “Teals”, running in seats previously thought safe. Nuclear power offers the perception that the party is taking climate change seriously even as it still serves its traditional constituency – a reality Nationals Senator Matt Canavan appeared to acknowledge during an hour-long interview with the National Conservative Institute of Australia in August 2024. The Queensland senator, a prominent defender of the coal industry, was frank in telling his interviewer how “nuclear is not going to cut it” and that the Coalition was “latching onto nuclear” to solve a political dilemma.

“We’re latching onto it as a silver bullet, as a panacea, because it fixes a political issue for us in that it’s low emissions and it’s reliable, but it ain’t the cheapest form of power,” he said.

The consequences of what comes next may be far reaching. Back in Ontario, a few minutes walk from where the first White Pines wind turbines were supposed to stand, Don Ross says he has been watching Australia from afar as an election approaches and the country faces a choice similar to the one once faced by his community. Ontario now has aspirations to build the world’s first SMR. Whether or not it actually happens, it came at a cost. For all the bluff and bluster, Ontario became the first place to tear out wind turbines in service to a nuclear vision in what Ross views as an act of sabotage. Australia, he says, now has a chance to avoid becoming the second.

“Nuclear is a bottomless pit,” he says. “I’m 70 now. I was 20 when all this started, when they were having open houses and talking about nuclear. I happened to live in Toronto when the same sort of people were promoting this, saying how great and wonderful it’s going to be.” “All of the things they said, none of it happened. They still haven’t worked out where to put the waste and they don’t like talking about that. I see no more reason for the industry to be different now than it was when it started. My advice to Australia? Two words: elections matter.”

An earlier version of this article described Canada’s resource minister as being concerned about Germany’s phase out of coal. That description was pulled from a talk given by Keefer in which he misspoke; the resource minister was concerned about Germany’s phaseout of nuclear. The piece has been updated to reflect this clarification. Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly described the Fraser Institute as having amplified Chris Keefer's work. We regret the error.