Photo of Discoverer Enterprise and the Q4000 working around the clock burning undesirable gases from the still uncapped Deepwater Horizon well in the Gulf of Mexico, 2010. Photographer: Spc. Casey Ware, 102d Public Affairs Detachment. Photo courtesy of the Department of Defense Visual Information Distribution Service.

A Florida law firm says a University of Louisville professor broke the school’s conflict of interest policies when he worked as a litigation consultant for BP at the same time that he published academic articles and presented on oil spill science.

The law firm sent a letter to the university’s president earlier this year detailing how professor emeritus and microbiologist Ronald Atlas allowed BP and Exxon to review and edit his work, which supported the oil companies’ claims that oil from BP’s 2010 spill in the Gulf and the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska degraded in toxicity and that the ecosystems could bounce back. The Downs Law Group, based in Miami, Florida, obtained emails between the professor and the companies through subpoenas in their lawsuits for personal injury and medical claims on behalf of cleanup workers.

“People should know if you are a scientist or a paid consultant,” said Jason Larey, an attorney at Downs Law Group. “When you’re a litigation consultant, you can’t conflict with your client,”he explained, which means you agree that your work won't conflict with the company's ability to make a profit. Such an agreement is incompatible with being an objective scientist.

Eleven workers were killed when the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded 40 miles off the coast of Louisiana. Thousands of people boated into the Gulf to try to stop the oil from coming to shore. Others were contracted to clean oil from beaches, collect the carcasses of dead birds, and wash the contaminated boats of fellow workers. In the wake of the explosion, BP launched a hiring spree of Gulf Coast academic researchers, going as far as trying to commission the whole marine sciences department at University of Alabama.

Larey says BP is now using the science it paid for in courtrooms to avoid paying workers who are dying from their exposure to BP oil and the chemical dispersants used to break up oil slicks. “The fossil fuel industry’s decades-long manipulation of science for corporate profit must end,” his firm’s letter to University of Louisville President Dr. Kim Schatzel reads. “Too many lives are being put at risk by research co-opted by industry to turn purported science into product defense.”

Atlas consulted for Exxon after the Valdez oil spill and was hired by BP in 2010 for similar litigation work. These relationships weren’t always obvious in his comments to media, published academic research and presentations. For example, in 2011, Atlas gave a TEDx talk on how spilled oil loses its toxicity with time as it is weathered and eaten by bacteria. “In the end though we’re going to be left with some compounds,” he said in the talk. “They’re going to be largely inert. They’re going to be like the asphalt roads that we drive on, where children drop their lollipops, pick them up, eat them, and don’t die instantly from that.”

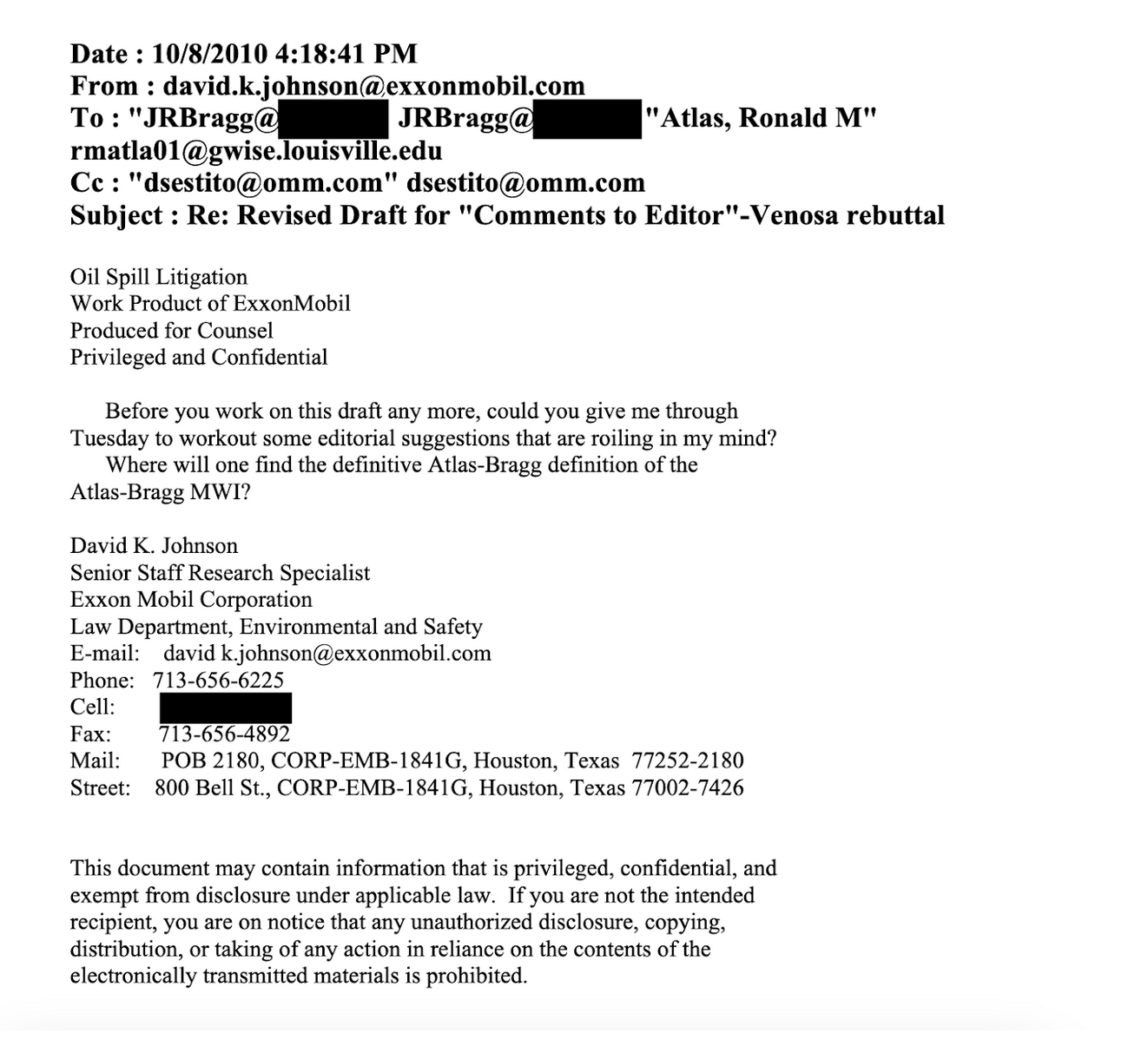

Emails show that Exxon Mobil helped Atlas craft a rebuttal to a scientific paper written by Environmental Protection Agency scientist Albert Venosa that was unfavorable to the industry.

“Before you work on this draft any more, could you give me through Tuesday to work out some editorial suggestions that are rolling in my mind,” Exxon’s Senior Staff Research Specialist, David Johnson wrote to Atlas in an email sent in October 2010, with the subject line “Re: Revised Draft for ‘Comments to Editor’ - Venosa rebuttal.”

Three months later, Johnson asked Atlas to submit an invoice for his work for Exxon. “There will be a few hours in January that deal with responding to Venosa,” Atlas wrote back. Atlas billed BP more than $48,000 for consulting in January 2011, records show.

BP said it could not comment on ongoing litigation. Atlas did not respond to requests for comment about the conflict of interest allegations. ExxonMobil and University of Louisville president Kim Schatzel also did not respond to requests for comment. However, in late February 2025, Rebecca H. Stahl, associate vice president and deputy general counsel for the University of Louisville, confirmed to Larey that his firm's letter had been forwarded to the university's Conflict of Interest Office for standard review.

Atlas is just one example of the oil industry’s use of academic researchers to shut down litigation against it, Larey said. The industry's fingerprints are particularly visible in the scientific literature about chemical dispersants, whether they work, and what kind of lasting impact they have on ecosystems.

"Generally, I see there being industry studies related to biodegradation and dispersants versus non-industry studies," he said, noting that most of the industry studies were conducted by Exxon-affiliated scientists, including Atlas as well as Terry Hazen, Governor’s Chair for Environmental Biotechnology at the University of Houston, and scientist Roger C. Prince. While studies conducted by industry-affiliated scientists found dispersants were effective and did not persist in the environment, Larey said, "studies by scientists outside of industry sponsorship have found that large concentrations of crude oil and dispersants inhibit biodegradation, or that dispersants were not effective at aiding natural biodegradation."

"Our understanding is that Atlas and other BP-retained experts were affiliated with Exxon prior to their Deepwater Horizon work, as many of the same scientists were also involved in the Exxon Valdez defense or had performed sponsored work for industry through API [the American Petroleum Institute] in the aftermath of Exxon Valdez," Larey said.

He added that BP required the scientists on its payroll to sign confidentiality agreements that prohibited them from sharing or speaking about the data they collected, effectively adding the researchers to the company’s legal team.

Two years before the BP spill, oil companies’ use of academic research to create favorable legal outcomes was called into question after a Supreme Court Justice acknowledged in the footnote of a 2008 decision that punitive damages research was largely paid for by one company. “Because this research was funded in part by Exxon,” Justice David H. Souter wrote. “we decline to rely on it.”

Fossil fuel companies continue to use their academic funding as a litigation strategy, Larey said. “When you retain all the scientists, the people who were harmed can't retain them,” he said. “This is still being used in court today.”

Sara Sneath is a journalist-in-residence at University of Miami's Climate Accountability Lab.