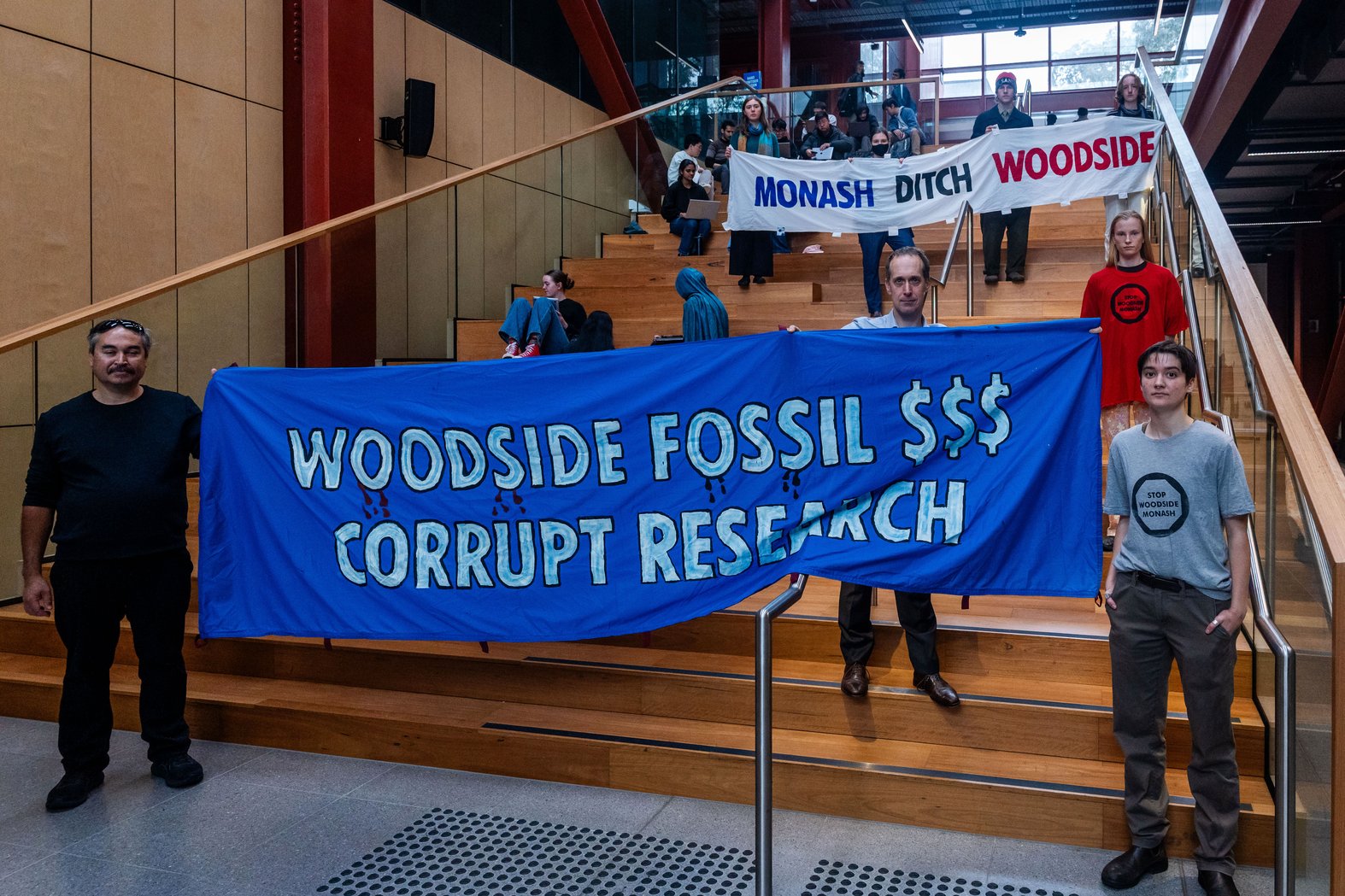

Photo: Student and faculty members of the Stop Woodside Monash group at Monash University. Photo by: Sean Davey.

The building is gorgeous from every angle. The five-story structure on Monash University’s Clayton Campus houses 30 classrooms, including a 360-person capacity lecture hall. Since construction finished in February 2020, it has won at least nine separate awards for its sustainable design that incorporates solar and passive systems to create ultra-low energy demand. The result is a sparkling feat of architecture and sustainable engineering, the pride of one of Australia’s most prestigious universities, which has positioned itself at the cutting edge of research on subjects like climate, ecology and sustainability.

The building is also named for the country’s biggest domestic gas producer, Woodside Energy, a company aggressively pursuing multi-billion-dollar gas megaprojects at a time when the World Meteorological Organization has warned that global average temperatures are on track to reach 2C warming by the end of the decade.

“It’s laughable—it’s so dystopian,” Carina Griffin says.

The 21-year-old Monash University student behind Stop Woodside Monash, a campaign pushing for the institution to divorce Australia’s biggest gas company, says The Woodside Building For Technology and Design is a “grim example of greenwashing at its best”. “It takes the meaning of Woodside away from the company that does the things an extractivist company does, and associates it in the minds of students at Australia’s largest university with this beautiful, green technology building, this shimmering image of the future, of technology, on campus,” Griffin says.

The Woodside Building For Technology and Design at Monash University. Photo by Sean Davey.

“Students say: ‘I’ll meet you at Woodside.’ Or: ‘I’ve got a class at 2 at Woodside’ and do not know what it is named after. That’s greenwashing at its finest.. Students at Australia’s biggest university do not think ‘Woodside’ and associate it with the biggest fossil fuel company in the country that is drilling off the Pilbara.”

Referred to by staff and students as “the Woodside Building”, the structure has become a physical manifestation of a battle that has pitted a group of staff and students against university leadership over Monash’s ongoing relationship to fossil fuel producers and, specifically, its partnership with Woodside. Since the campaign began roughly 18 months ago, Griffin, a fourth-year law and science double major, says they have been calling for the university to go beyond divestment and adopt a policy disassociating itself entirely from all fossil fuel producers – the same way it treats tobacco companies.

Now, it appears change may be possible. Following multiple questions by Drilled about the partnership, Monash said the arrangement will conclude in December and that "any future arrangements will be considered in alignment with our ESG statement, which is currently being informed through consultation with staff and students, and the principles of academic freedom and the University’s governance, risk and policy frameworks.”

“The university’s position at the moment is that Monash doesn’t invest directly in fossil fuels,” Griffin said. “But it has no problem with companies like Woodside investing in the university. We want to change that.”

Marriage of Convenience

Monash University isn’t the only Australian institution with ties to fossil fuel companies and their industry associations. Where Monash leads, however, others tend to follow. According to the World University Rankings it is the second-highest ranked Australian university in the world as of 2025 and belongs to the Group of Eight, a rough equivalent to an Ivy League university in the United States. The institution has also sought to leverage its historical reputation as a progressive, forward-thinking institution as part of its promotional material, including in a campaign called “Change It”.

It was this context that made the university vulnerable in 2014 to an earlier divestment push coordinated, in part, by campaign organization 350.org working with a group called Fossil Free Monash. After two years Monash University’s leadership appeared to concede. The apparent victory, however, came with a catch. When the university published its first ESG statement in 2016 outlining how it planned to enact this pledge, the document stressed that a review had shown Monash University held no direct investment in fossil fuel producers. The university promised to focus on screening coal companies from its indirect investment portfolios. Oil and gas were not mentioned.

This line—with its gas tanker-sized exception—became Monash University’s default position on divestment, one that allowed it to ink a partnership deal with fossil fuel producers like Woodside the same year it made its divestment commitment. In 2016, it signed an agreement to create the Woodside-Monash FutureLab, a “globally-connected innovation hub that supports technological innovation and collaboration in material engineering, additive manufacturing, data science and information technology.” Under the arrangement, the company contributed $10m (USD $6.52m) over five years towards the center, which was launched by then minister for resources, energy and Northern Australia, Josh Frydenberg.

The relationship was expanded three years later when, in July 2019, Monash and Woodside “joined forces” to form the Woodside Monash Energy Partnership, pitched by the university as a “natural extension” of its previous arrangement, that aimed to “develop innovative responses to real-world challenges through a long-term research partnership”. Under the agreement, Woodside and Monash would jointly “invest” $40m (USD$26.09) over the next seven years—though the precise split and the specific obligations were never disclosed—and the company would contribute an additional $16.5m (USD$10.76m) to the construction of a new, highly sustainable building that included naming rights (the future Woodside Building).

Lincoln Turner, a senior lecturer in the School of Physics and Astronomy and a member of Stop Woodside Monash, says the Woodside partnership initially caused some disquiet among university staff. This grew as the Black Summer Bushfires burned up and down Australia’s east coast and in parts of South Australia in 2020. An effort to organize a broad response by staff, however, ended when the pandemic forced a huge logistical effort to shift classes online.

“I was organizing, with the help of the union and some colleagues, to start building a staff campaign to say to the university, ‘this is greenwashing, Woodside is appalling, don’t do this partnership. Dump the partnership, un-name the building, get your act together,’” Turner says.

“Two days before the Covid lockdown hit, I spent the days driving around Melbourne buying AV equipment so we could keep teaching. And then we all got locked up at home.”

Fast forward three years and the current grassroots effort, he says, kicked off in late 2023 when Carina Griffin put up a poster asking people if they wanted to do something about Woodside’s presence on campus. A core group of 30 people have since become involved with the campaign, but until this week the university leadership response had been to wait them out. Meetings, the organizers say, have gone nowhere, informal approaches within the academic hierarchy have been waved off, and efforts to find out basic information about the Woodside partnership agreement—even through Freedom of Information requests—have been frustrated. In response, the university has consistently defended its ongoing relationship with the company by saying it “supports Woodside’s transition to net zero by 2050,” a claim the campaign group rejects.

Simon Campbell, a senior research fellow at Monash who is also involved with the campaign, says the partnership with Monash University gives Woodside, a company that dominates the Australian state of Western Australia, an outpost on the east coast, where it is less-well known. The astrophysicist says he believes Woodside has no intention of giving up gas and is actively planning for a future where it can continue gas extraction past 2050.

“The whole line from management was that Woodside is decarbonizing; that’s certainly what the front-facing messaging was,” Campbell says. “Management took the bait and what’s happened is literally the opposite. Woodside have doubled down on fossil fuels. They’re expanding fossils when the International Energy Agency is saying there is no need for new fossil fuels to meet net zero targets.”

And the list of Woodside’s new gas projects is extensive. In late May, Woodside received conditional approval from the Australian government to extend the life of a massive gas processing plant on the Burrup Peninsula in the remote far north coast of Western Australia until 2070. That project, known as the North West Shelf, began life as Australia’s most complex gas project in the late 70s, and according to one analysis by The Australia Institute, will be responsible for more emissions than all of Australia’s coal-fired power stations each year. The operational extension faces potential legal challenges but when finalized it will serve as a crucial step needed for Woodside to bring online the AUD $16bn (USD $10.5bn) Scarborough gas project and the AUD$30bn (USD$19bn) Browse development near the Scott Reef, a sensitive marine environment. These, however, aren’t the company’s only major projects. In the U.S. state of Louisiana, Woodside will sink USD$17.5bn (AUD $27.17bn) into developing a gas processing facility to enter operation by 2029. Moreover, though the company has previously suggested that the gas it exports will help decarbonize countries in South East Asia, a 2024 study by the U.S. Department of Energy showed otherwise. For every unit of coal replaced by gas, two units of renewable energy were displaced.

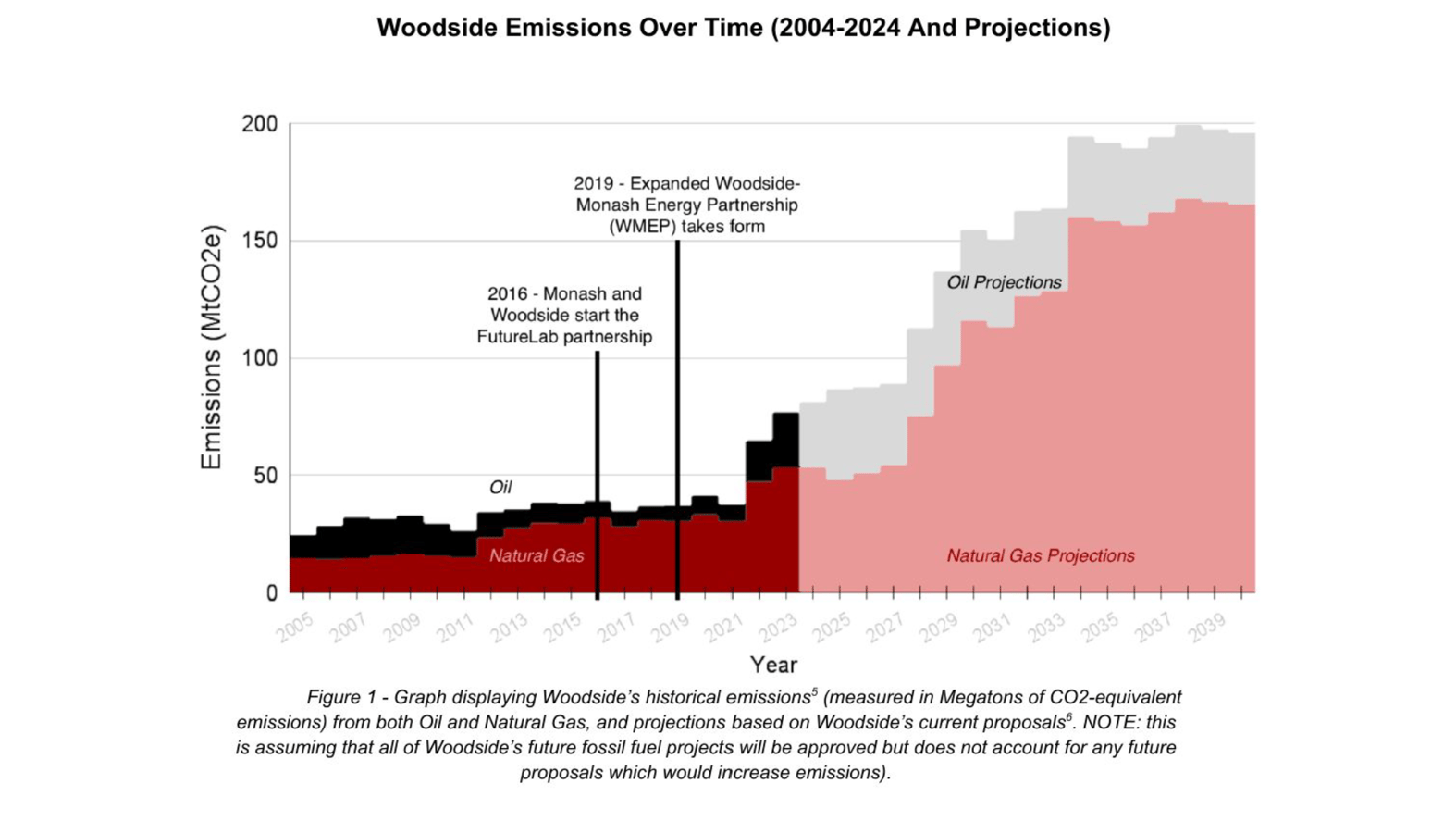

Staff and students involved in the Stop Woodside Monash campaign, which was endorsed by the student association and the Monash University branch of the National Tertiary Education Union, say the company’s actions show it is not serious about decarbonization. To emphasize the point, Campbell graphed Woodside’s projected emissions. His calculations show Woodside’s emissions profile won’t just double but quadruple over the next decade.

Graph by Simon Campbell and Hunter Williams.

“This is the same conversation that happened with tobacco,” Turner says. “Monash does lots of good things on climate and ecology. We have outstanding researchers here on a wide range of subjects and research centres dedicated to various aspects of climate change. By tying itself up with Woodside, Monash gives it the reputational benefit and the value of this excellent work that's going on. Woodside wishes to look better by association with the university at the very same time the university is harming its own reputation and undermining its good works.”

Monash University did not respond to questions about what naming rights Woodside was given under the terms of its partnership agreement and specifically whether these are lifetime naming rights.

Fine Print

The issues, the campaigners say, run deeper than the partnership to core questions about transparency, academic independence and a lack of trust in the university’s leadership to engage in good faith. For example, despite repeated statements by the university that it does not hold direct investments in fossil fuels (Australian universities are largely publicly funded and unlike U.S. universities do not generally hold large private endowments), records show the institution does hold shares in carbon majors indirectly through its investment funds.

From 2018, the university’s ESG documents show Monash made good on its promise to divest and began shifting money into an investment fund managed by Russell Investments that purported to limit its exposure to coal. The University upped its stake in the firm’s Low Carbon Global Shares Fund from 10% to 19% in 2022. There was, however, a catch. Though the fund does not invest in companies involved in the production of coal, landmines, tobacco, biological and chemical weapons, or uranium, an information booklet produced by the investment firm explicitly states “it can still hold companies with fossil fuel reserves”. A list of the 1641 companies whose shares are held by the fund reveals that ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, Shell, ConocoPhillips, TotalEnergies, Eni, Marathon, Devon, Suncor and Hess are among them.

Much to the frustration of staff and students, university leadership previously suggested it would be difficult to fully divest. Those involved in the campaign say this is not true and suggest the university could do so without having to move to a new firm. Russell Investments has offered a fossil-free fund since 2020 that does not invest in companies with fossil fuel reserves or those that draw more than 10% of revenue from oil, gas and coal production.

Brett Morgan, asset management and superannuation funds campaigner with Market Forces, an organization with no involvement in the campaign, says that, broadly, divesting from fossil fuels is not as difficult as it may have been ten years ago.

“Ultimately if an institution like a university is enlisting an asset manager to invest on their behalf, they do have a say in where their money is being invested,” Morgan says. “It depends on the specific agreement and how long the time frame is, but ultimately there is no reason why total fossil fuel divestment can’t be achieved.”

“It depends on how they hold their investments; a university might outsource its investment management to managers, through an agreement called an investment mandate. All it would take is for the university to tell the asset manager where they want their money invested.”

Student and faculty members of Stop Woodside Monash protest in the Woodside building. Photo by Sean Davey.

An Investment In Industry’s Future

Woodside takes significant pride in its partnerships with schools and universities in the jurisdictions where it operates, treating these relationships as examples of good corporate citizenship.

“Woodside has a strong history of investment in education, with our partnerships creating lifelong learning opportunities that build capabilities of the future,” a Woodside spokesperson said. “We partner with universities through research collaborations, educational programs, internships, community development projects, workforce development, public engagements and funding initiatives to promote sustainability and innovation in the energy sector.”

John Cook, a senior research fellow at The University of Melbourne and a former research academic with Monash who studies greenwashing, described some of these partnership arrangements as an “insidious form of misinformation”.

“Greenwashing, the general purpose of it, is to convey the impression of a good citizen. A corporation being a good citizen,” he said. “And usually it’s more specifically behaving in an environmentally friendly way.

“One way companies greenwash themselves is through association with universities like Monash. That’s why they’re doing it, for the halo effect they’re getting for being part of Monash.”

In Australia, the evolution of many current industry programs can be traced back to the Schools Information Program in 1991. Its precise origins are unclear, but the basic idea for a program to introduce high school kids to oil and gas production began with the Petroleum Club of Western Australia, who then coordinated with the national industry association. The program targeted 15-year-olds in 22 metropolitan schools around the Western Australian state capital, Perth. It involved the delivery of a six-week course design to be incorporated into the state curriculum, and field trips to working oil and gas facilities. Individual companies, including Woodside, later signed on as partners to help in delivery.

Woodside, in particular, took the idea of an organised educational program and ran with it. In one later example, Woodside partnered with Earth Sciences Western Australia in 2012 to create the Woodside Australian Science Project (WASP). WASP has since produced and distributed earth science school materials that teachers anywhere can download anonymously from the internet. Some of these materials include worksheets for Year 10 students on the “greenhouse effect” that described humanity’s role in the “rapid warning of our atmosphere” through the “burning of fossil fuels and industry” as “a point of some debate”. Other Woodside workshops have sought to teach children about geology by having them demonstrate how drilling oil worked by sucking Vegemite from sandwiches using straws.

More recently, Woodside has directly funded two educational projects in Louisiana, in the United States. The company is listed as a sponsor of the Gulf Coast Carbon Center alongside other carbon majors like ExxonMobil, Chevron and Equinor. The GCCC is an organization that has helped deliver educational programs on subjects such as Carbon, Capture and Storage (CCS) in schools in partnership with Texas A&M University. A Woodside spokesperson said the company “does not have any carbon capture and storage (CCS)-related programs in Louisiana.”

Very few of these initiatives are charity on the part of oil, gas and even coal producers. As Drilled has previously reported, the world’s biggest oil and gas companies treat strategic university partnerships and research investments as an extension of their marketing strategies. In one example, emails obtained from Chevron, a company which operates in Australia and was involved, through a joint venture, in the first discovery of oil in 1953, showed the company had concerns that communities and civil society groups were increasingly “attempting to link human rights to climate change and hydraulic fracturing debates” amid calls for fossil fuel producers to pay for climate harms. It also noted that the company’s partnership agreements with schools, arts and culture institutions, and community organizations helped increase “support for our operations in their communities by a margin of 2:1”.

Australian oil and gas companies have treated their educational partnerships similarly. A 1994 paper published by the Australian Petroleum Production Association—today known as Australian Energy Producers (AEP)—explicitly stated industry educational programs “aim to improve the public perception of the industry and to effect the way it is portrayed within the education system.”

“By assisting the wider understanding of petroleum matters, the industry will enhance its own viability and ultimately its long-term survival,” it said. “An involvement in education can create familiarity and reach the people who have a stake in the industry’s future.”

The Italian Connection

Monash University, when challenged, has so far sought to shift focus onto more positive elements of the partnership, such as the recent launch of start-up MonSol, a company that develops lower-cost renewable energy technologies and which originated from within the partnership.

The university did not respond to detailed questions from Drilled and did not make a representative available to speak to elements of this story. A general reply to issues raised by critics of the partnership reiterated that the university has “committed to addressing climate change through our research and education in collaboration with industry, governments and communities,” and that “Woodside is one of many partners in our vibrant ecosystem that we work with to create solutions for real-world application.”

“We are working with Woodside Energy to help them determine the best pathways and technologies to enable them to decarbonise their operations and to provide the products and services needed to help their customers decarbonise,” it said.

“Our partnership supports Woodside’s transition to net zero by 2050, while Monash targets net zero for our operations by 2030,” it continued. “Through our research partnership, we are working to support Woodside to lead in producing, transporting and utilising hydrogen, ammonia and other fossil fuel substitutes at the scales required to transition to a net zero carbon future.”

The available evidence, however, suggests the university’s relationship with Woodside went beyond a narrow focus on engineering and business-related research, to include legal, social, political and policy issues that specifically address opposition to the company’s proposed gas developments.

In June 2024, the University hosted the exclusive Climate Change and Energy Transition Conference at its Prato Centre in Italy in partnership with Woodside. The company acted as a host and sponsor for the gathering of 50 academics and business people, and was credited as a “travel award sponsor” for early career researchers and students who wanted to attend. A company spokesperson said “no additional funds” were provided outside the existing partnership arrangement. Three Woodside employees, including its head of partnerships served on the organizing committee but only two staff attended.

Among the keynote speakers was Tim Wilson, then a former conservative Coalition MP who would later re-take his seat by defeating climate-conscious Independent incumbent Zoe Daniel in the 2025 election. Wilson, the former head of the Monash student association during his undergraduate studies, previously served as the Director of Climate Change Policy at the Institute of Public Affairs, a right-wing Australian think tank that is hostile to the science of climate change and environmental regulation. In that role—one not specified on Wilson’s LinkedIn—he promoted the work of climate deniers.

A call-out for papers to be presented at the conference in some cases employed emotive language commonly used by oil, gas and coal CEOs to describe activist groups and NGOs opposed to their activities. One proposed topic entitled, “Exploring the Intersection of Social Media, Cancel Culture, and Lawfare in the Energy Transition Investment and Regulation”, asked “How do social media, ‘cancel culture’ and lawfare interface with the pace and scale of investment and regulatory approval needed for the energy transition?” Another sought to address “Activism’s Influence on Emissions Reduction Efforts” by asking, “What is the role of climate activism/nimbyism and climate solution denialism activism/nimbyism in thwarting emissions reduction?”

A Woodside spokesperson said the “speaker program and call for papers was designed and agreed to by the members of the organising committee”.

“Central to the conference was discussion on how climate change policies interact with economics, energy security, social policy and governance,” they said. “The conference underscored the need for a holistic approach that embraces diverse perspectives and solutions.”

“It also highlighted the need for collaboration among academia, industry and government to overcome political polarisation and ensure inclusive decision-making processes. By fostering dialogue and knowledge exchange, the conference aimed to pave the way for more effective and sustainable solutions to the climate crisis.”

The language in the call-out for papers is similar to that commonly used by Australian oil and gas companies when talking about protesters and activist groups critical of their activities. In one example from late May, the Australian Energy Producers held its annual conference in Brisbane. It included a panel discussion directly addressing what it described as the “rise of environmental activism and law,” framing climate activism in terms of conspiracy.

“Environmental activism and 'lawfare' in Australia has become a well-funded and resourced machine that has set its sights on disrupting and delaying the development of natural gas projects,” the event description read. “From protesters, placards and billboards to public disobedience and attacks on the private residences of executives, those opposed to the industry are adopting increasingly extreme tactics to stop or frustrate projects.”

Among the participants on the panel was the Executive Director of the Menzies Research Centre, a centre-right think tank, the CEO of domestic Australian oil company, Santos, and Woodside CEO Meg O’Neill, who currently serves as AEP chair.

The conference landing page is no longer available on Monash’s website and only fragments remain, including the suggestions for papers. A full copy, however, has been preserved by the Wayback Machine. Monash University did not respond to detailed questions from Drilled about why the information was absent or to a request for copies of papers submitted to the conference.

The Woodside building at Monash University. Photo by Sean Davey.

Exceptions

Monash University has already been talking to Woodside about renewing its partnership even as it has pledged the decision over its future will be “considered in alignment” with the University’s ESG policy—a document that is currently under review with the new version yet to be released. According to the University’s own timeline, a green paper outlining its new policy was to be released by the end of April, with consultation among staff and students to be carried out between May and July. No document has yet been made public.

To date the university has not offered staff and students a clear timeline for the release of this new policy, according to Turner, who says the university has not been engaged in meaningful consultation with staff and students about the policy, and has refused to respond to basic questions about the process.

“Until we have an ESG policy that has been genuinely discussed and debated by staff and students at the university, and we can see it to be explicit and clear about excluding future engagement with fossil fuel companies, then I will have no confidence that we won’t find ourselves in this situation again,” he says.

Turner adds that any new ESG statement needed “genuine buy-in from staff and students, general consultation,” but also pointed to provisions of the University’s 2025 Risk Appetite Statement that appeared to suggest Monash could continue to partner with companies whose activities were in conflict with its policies. The document says Monash is “averse to entering or maintaining partnerships where the activities are directly inconsistent with the University’s strategy or values (including our ESG statement)” but says it maintains a “cautious appetite for entering or maintaining partnerships with organisations that undertake activities inconsistent with the University’s strategy or values (including our ESG statement).” It also states: “However, we may consider entering into partnerships with such organisations where the proposed activities would not cause ethical or reputational consequences.”

The latest Risk Appetite Statement was approved following a separate campaign by Monash students last year to force the university to divest from defense companies with ties to Israel over the country’s ongoing siege of Gaza and a widespread perception at the start of the year the conservative Coalition party would win government at the 2025 Australian federal election in May. It does not explicitly name tobacco companies, weapons manufacturers or fossil fuel companies.

“Neither the ESG policy or the Risk Appetite Statement, or any other document I’ve seen that is public, says anything about fossil fuels or arms companies, and interestingly, they don’t say anything about tobacco, even though no university in Australia would consider working with a tobacco company,” Turner said.

Those who now want Monash to divorce Woodside point to these documents, and the Prato conference in particular, to illustrate their concerns: the potential for any good done by the university to help smuggle in the bad. Money, they argue, exerts its own gravitational pull that can attract even fiercely determined and independent researchers. The result is that, over time, research teams will focus on subjects beneficial to the commercial interests of the company and be pulled away from those areas which may be in conflict with it. In that way, they say, the partnership threatens to warp Monash University’s research output.

The academic research in this area suggests these concerns are not without merit. There is already a large body of literature, particularly in the medical field, that has examined conflict of interest and pro-funder bias in research outputs. The question researchers are now turning to is: how are fossil fuels any different?

One paper published in the peer reviewed journal Nature Climate Change in 2022 concluded that it’s not. The authors carried out a sentiment analysis that sought to understand how positively energy research centers talked about methane gas when they received funding from a fossil fuel producer. The analysis considered 1,168,194 report sentences and found groups funded by the fossil fuel industry were “systematically more positive when discussing natural gas than other academic centers less dependent on fossil funding.”

Columbia University Professor Douglas Almond, lead author on the study, said the analysis found the “magnitude of pro-fossil sentiment” mirrored the language used by industry groups, but also resulted in fossil fuel funded energy center’s speaking less positively when writing about renewable energy. The results offer a practical demonstration of how companies sought to associate themselves with academic institutions to attain legitimacy and credibility, an exercise in influence that Prof Almond said “stems from the perception that [energy centers] are scholarly and unbiased.”

“I think [fossil fuel companies] do this in part because universities are perceived as independent.” Almond said. “Reports from a trade group have less impact than those that are perceived as more independent and scholarly.”

Almond said that individual researchers at these institutions might be rigorous and independent, and some may refuse to work with the company, but not everyone is immune.

“There are terrific people doing terrific work in these centers,” Almond said. “Our concern is that a more subtle influence exists for a subset of researchers, and one that imparts a systematic bias on average.”

The implications of these sorts of relationships can be profound, particularly when academic research is relied upon to set policy, Griffin says. Like others, Griffin supports Monash and believes in its mission as a university, but says the Woodside Building represents a fatal contradiction. When studying climate change as part of her environmental science specialization, Griffin attended a class that reviewed the possible projections for how bad things may get. There was no good news, she recalls. In one week, she said, there was a link to the university’s counseling service after every slide in the presentation because the reality was so confronting. Afterwards, when Griffin left, she walked by the Woodside Building.

“You couldn’t write better satire,” Griffin says. “You know, I’m from the country. I decided I was going to get out of my home town and study environmental science because I loved it and because I thought Monash was a good place to do that.”

“I want to believe in this institution, and I want to believe in a future that is not just left to companies like Woodside with no one to stand in the way.”