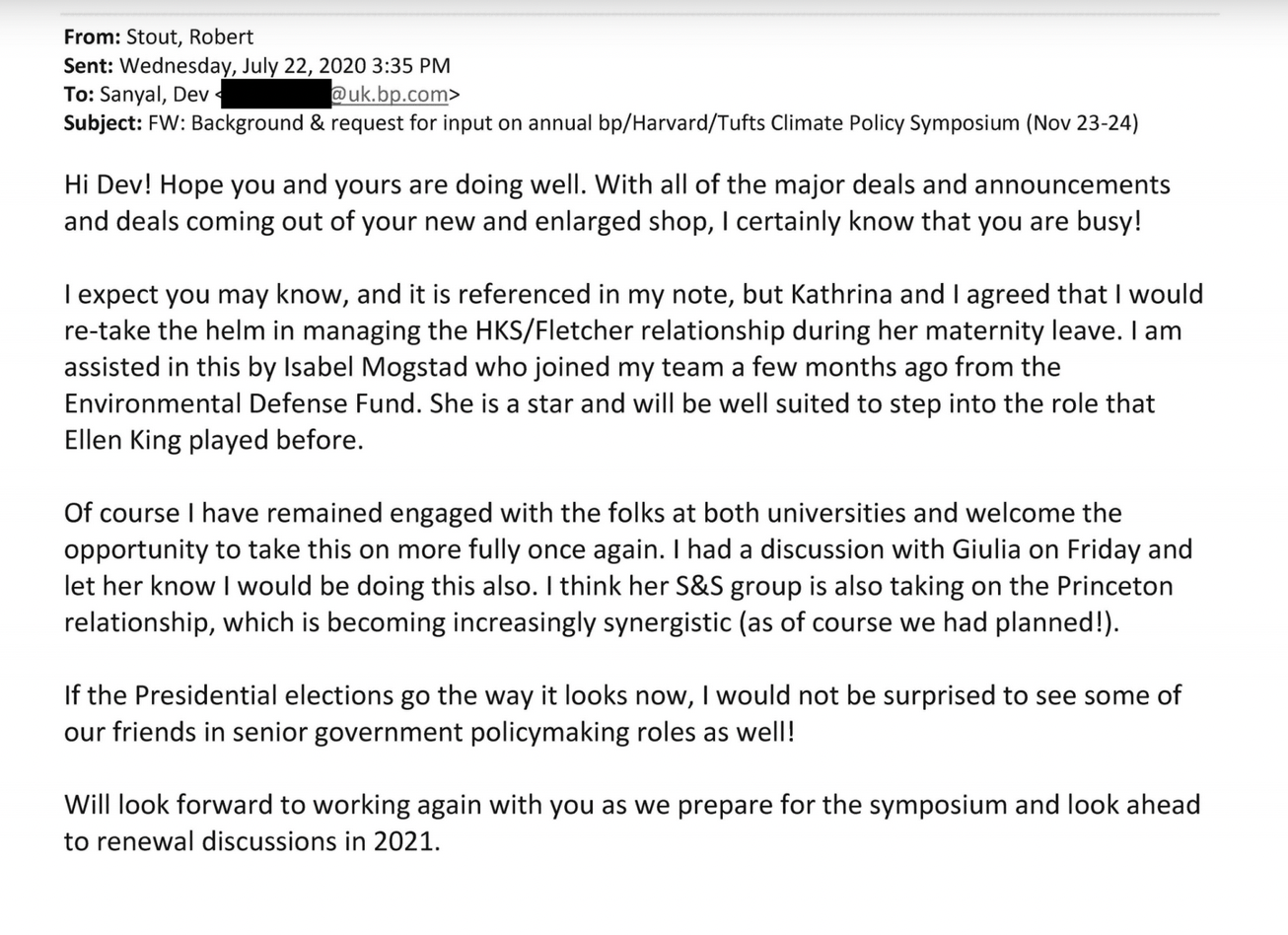

In July of 2020, Robert Stout, then the head of US policy at BP, wrote an email to his colleague laying out a few updates to the oil company’s relationships with Harvard, Tufts, and Princeton Universities, where BP funded various programs. Stout wrote that Princeton was becoming “increasingly synergistic” with the oil company—“as of course we had planned.”

“If Presidential elections go the way it looks now, I would not be surprised to see some of our friends in senior government policymaking roles as well!” Stout wrote of BP’s counterparts at Princeton.

The “synergistic” nature between Princeton and BP, which has funded the university’s Carbon Mitigation Initiative (CMI) for more than 20 years, is no accident. Big Oil and U.S. universities have long enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship, as fossil fuel money has flowed to academic centers for decades in exchange for research that advances their objectives, access to policymakers, and civic goodwill. Yet this relationship has for years gone mostly unquestioned by mainstream media and regulators.

Tomorrow’s Senate Budget Committee hearing—and the wealth of subpoenaed documents and bicameral report released in advance of the hearings—mark the first time the U.S. government is calling out the relationship between academia and Big Oil. As students on campuses across the country revolt against their universities’ financial relationships with companies profiting off the war in Gaza, the hearing comes at a time when U.S. academic powerhouses are already in an uncomfortable spotlight.

What, exactly, is in these documents that illustrate how Big Oil works with academic institutions to launder its image and lay the groundwork for industry-friendly policy? Here are some key takeaways.

New Numbers

In 2023, research from Data for Progress estimated that fossil fuel companies have donated at least $700 million to 27 US universities over the past decade. Calculating the exact breakdown of these numbers can be an inexact science. Funding streams and financial ties on campus can become complex, and the vast majority of university research centers do not disclose their donors publicly. Even when asked directly to disclose their fossil fuel-backed research donations, only a handful have done so.

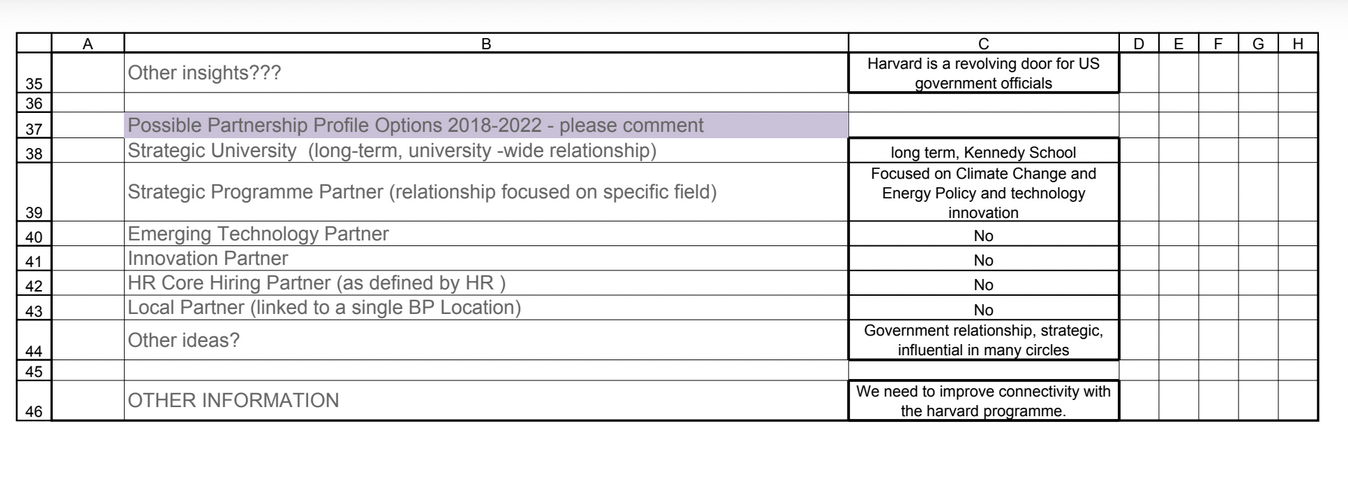

Previously, only the University of California at Berkeley has provided a complete accounting of its fossil fuel-funded research ($108 million from 2010 to 2020). The new documents put some real numbers on BP’s relationships with Princeton, Tufts, and Harvard. . According to the Senate report, BP funneled between $2.1 and $2.6 million to the Princeton CMI program between 2012 and 2017. BP also paid $416k to Harvard and $250k to Tufts each year between 2019 and 2021 for partnerships with programs at Tufts’s Fletcher School and Harvard’s Kennedy School. The focus of these grants is worth noting, too: Harvard’s Kennedy School and Tufts’s Fletcher School are both focused explicitly on policy; at Tufts, BP funds the Climate Policy Lab. These donations don’t just give BP a window into what some of the country’s top public policy schools are researching, it also gives them influence and access to future policy makers. On a spreadsheet detailing the value of these grants, for example, it’s noted that “Harvard is a revolving door for U.S. government officials.”

“BP is committed to transitioning from an international oil company to an integrated energy company,” the company told Drilled in response to a request for comment. “To do this, we are investing in today’s energy system while helping to build out tomorrow’s.”

While the new documents contain the most information on the relationship between BP and US universities, BP wasn’t alone. Exxon planned between 2016 and 2017 to donate hundreds of thousands of dollars to schools across the country, per the Senate report: “$600,000 to MIT; $325,000 to George Washington University’s Regulatory Studies Center; $175,000 to Indiana University’s School of Public and Environmental Affairs; $140,000 to Stanford University; and $50,000 to the University of Massachusetts Amherst.”

In 2017, Shell announced it would spend $25 million over 5 years on funding Berkeley’s Energy Biosciences Institute. In an email uncovered by the subpoena, Shell wrote it had “plans to ‘embed’ Shell scientists at UCB and likewise invite faculty to spend time at Shell’s research hub to further foster deep collaboration.” (EBI was originally created with a $500 million commitment from BP to develop “a sole focus on biofuels”; Shell acknowledged in the email that it was “taking advantage of the huge sunk costs already borne by BP” in funding the program.)

In late 2020, academics at Princeton gave BP a heads-up on a major study it issued modeling pathways for the U.S. to reach net zero by 2050. In emails revealed by the Senate investigation, one BP staffer noted that BP contributed “just under” $2 million of the study’s funding through its partnership with Princeton. (Whether or not this was an additional expense on top of the regular institutional gift was not made clear.)

“BP supports the High Meadows Environmental Institute’s Carbon Mitigation Initiative with an annual contribution that is completely controlled by Princeton academics,” Princeton told Drilled in an email. “The funder has no involvement in the selection of specific research projects for support, in the execution of the research projects, nor in the presentation of final results. All HMEI research is submitted for peer review by independent, external academic experts.”

Not all oil companies’ relationships with universities were accounted for in the new documents. The Senate report documented that despite public partnerships with universities across the country, Chevron did not “[produce] relevant documents on this subject, even though the scope of the House Oversight Committee’s subpoena covered these documents.”

What Oil Companies Pay For

Importantly, the documents also lay out in clear detail what, exactly, fossil fuel companies expected their university money will be going towards: research that supports their objectives, access to academics and policymakers, and positive public associations with climate solutions.

“Our policy programs at Harvard and Tufts provide BP access to unparalleled expertise at the forefront of research in the areas of climate change science, technology, and policy,” one undated document from Dev Sandyal, then an executive VP at BP, explained to staff. The document sought feedback on the programs within these two universities, which, the note says, has “been an opportunity for [BP] to provide a business perspective to help shape international policy thinking in low carbon energy discussions.”

The 2020 Princeton net zero report is a key example of the company leveraging university research for positive PR. In an email discussing press strategy ahead of the report’s release, Omayma Khan, a BP communications official, wrote to other executives that the study “plays to our aims of helping the world get to net zero.”

“The team that worked on [this report] are already advising Biden’s transition team,” Khan added. In a separate email, Stout wrote that BP would make “a continuing effort to leverage the study with the USG [U.S. government].”

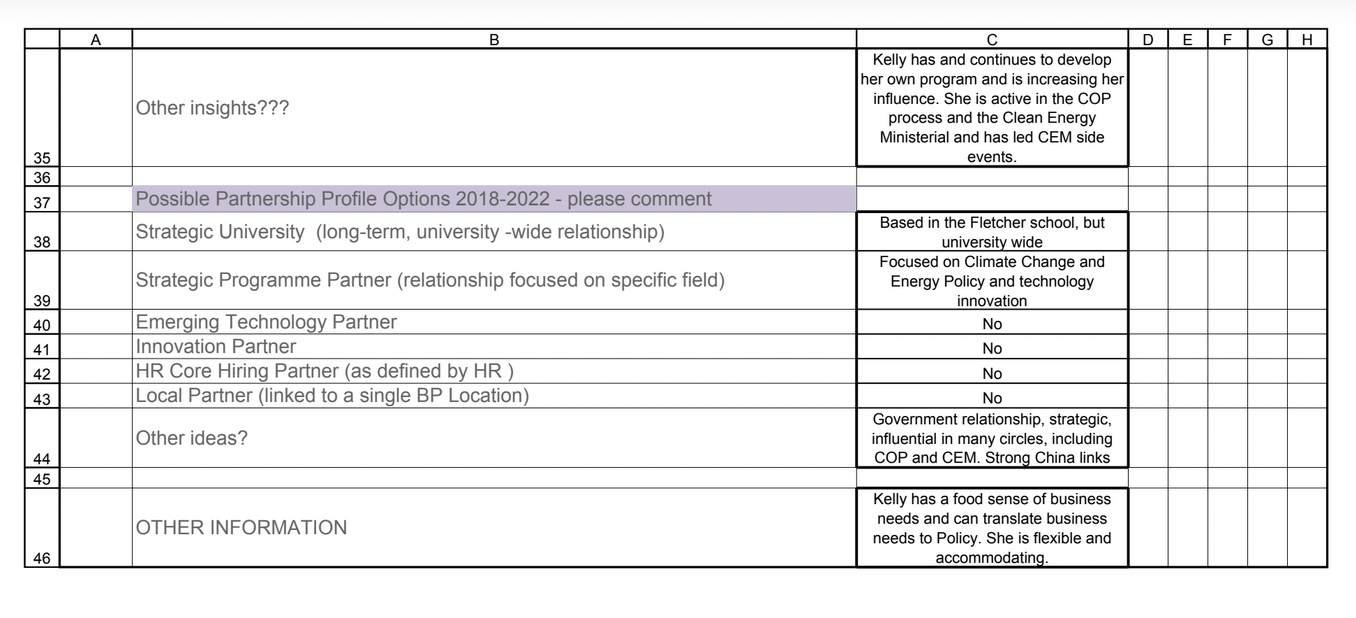

Access to staff at these programs—and their relationship to policymakers—was a clear focus for BP in keeping up these relationships as well. Representatives from universities across the country routinely pop up in industry invite lists; BP’s invite list for a private reception at CERAWeek in 2018 included Jason Bordoff, the head of Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy, as well as staffers from the Kennedy School, Stanford’s Natural Gas Initiative, and Georgetown University. The same BP document that references Harvard as a “revolving door for U.S. government officials” notes that “Kelly”—referencing Kelly Sims-Gallagher, the Dean of Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy—is “active in the COP process,” calls her “flexible and accommodating” in her relationships with businesses, and notes that Tufts is “influential in many circles,” including COP and the Clean Energy Ministerial.

In a 2020 email to high-level BP staff describing the Harvard and Tufts partnerships, Stout writes about how many former Obama administration officials are involved in both programs, calling out their “deep insight, credibility, and influence with US and global policymakers.”

Regardless of the independence of Princeton’s research, BP often discussed leveraging its relationship with Princeton to advance its own priorities. In 2020, a BP VP emailed notes from a call with Stephen Pacala, a researcher at Princeton, where they noted their recommendation of developing an infrastructure program “with an emphasis on CCUS [carbon capture, usage and storage]—building ‘backbone’ of pipelines to transport carbon.” In a 2017 email, Stout called Pacala “a big advocate” for BP making its case for natural gas. BP also used its relationship with Princeton as part of a 2020 presentation to the Rocky Mountain Institute, a nonprofit influential with renewable energy circles, noting how it intended to “advance methane science” through its partnerships.

In one 2018 document, BP also discussed a plan to “advance and protect the role of gas—and BP—in the energy transition” following negative press around methane emissions from natural gas. The plan included proposals to fund whitepapers from researchers at Princeton and Imperial College in London “highlighting [the] role of gas as a friend to renewables.”

Not All Programs Created Equal

Simply buying an association with a top-level university is just the first step in the Big Oil PR playbook. The documents reveal that some oil companies are also constantly reevaluating their relationships with universities to maximize their rates of return.

One spreadsheet included in the tranche of released documents lists meticulous details of each of BP’s partnerships with Tufts, Harvard, and Princeton. The spreadsheet includes ranking the universities’ research programs as aligned with BP’s “strategic priorities”—like the “shift to gas,” “advantaged oil” (an industry term used to describe the most desirable oil to be extracted during the energy transition). The spreadsheet also includes details like the number of graduates hired from each school by BP, the number of visit days or meetings for BP executives, and scoring each academic institution on its “Industrial Relations Strategy Maturity” (all schools scored a “Medium” ranking.)

In notes from a 2016 meeting, BP executives mention that the Harvard “relationship began as the climate policy adjunct to the Princeton CMI technical work;” BP executives discussed how to reduce contributions to a program that had, in their eyes, grown beyond its scope in order to “avoid damaging the Harvard/BP relationship.”

“The CMI discussions are directly relevant to BP, whereas the Harvard/Tufts discussions are directed by the Universities and much less relevant to BP,” the notes read.

“The Fletcher School's Climate Policy Lab received a general support grant from BP which concluded at the end of 2021 and has not been extended,” a spokesperson from Tufts told Drilled in an email. “Throughout the duration of that collaboration, Fletcher's research was conducted autonomously and without any influence from the funding source. We remain committed to conducting rigorous, unbiased research that serves the public interest.”

How Academics “Sharpen Corporate Perspective”

The new documents also show how academic centers helped oil companies refine public messages on climate change. A 2016 presentation to BP by Pacala and Robert Socolow, the co-director of the Carbon Mitigation Initiative at Princeton, included a slide titled “Risks of climate change to BP.”

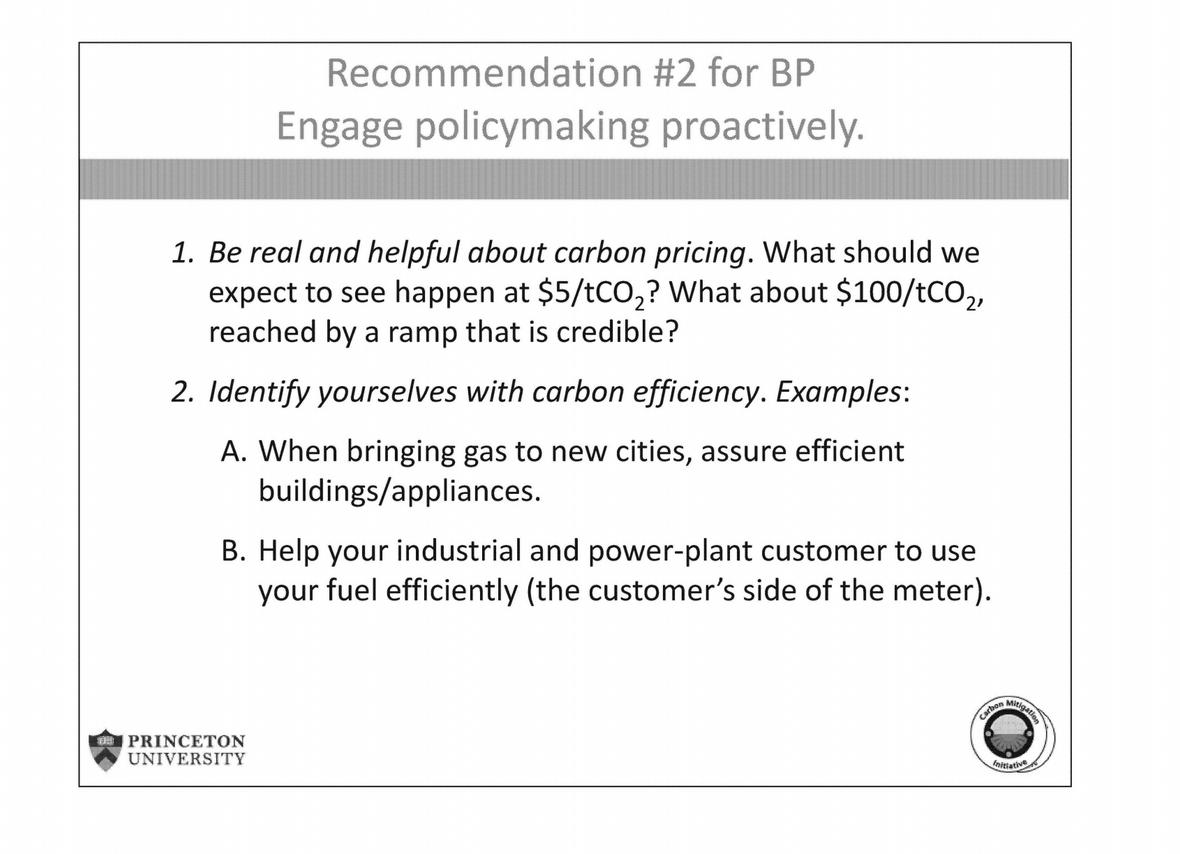

“Effective climate policies can emerge that discourage fossil fuel consumption, that impose environmental performance standards on production processes, and that subsidize or otherwise promote efficiency and low carbon energy,” the slide reads. In the next slide, Pacala and Socolow point out that “BP benefits when CMI disseminates sound information that supports effective public policy discussions.” The center’s research, the researchers point out, also helps “[sharpen] BP’s corporate perspective on climate change.” Later in the presentation, Pacala and Socolow make a series of recommendations to BP, including to “engage policymaking proactively.”

“Identify yourselves with carbon efficiency,” the slide says.

In July of 2019, staffers from Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy, including Jason Bordoff, emailed executives at BP a draft of a chapter on carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) that would be included in an upcoming report from the National Petroleum Council. Gardiner Hill, then the company’s VP of carbon, emailed back several thoughts.

Hill recommended that the chapter “be clearer and bolder on the role of the USA in the emerging energy transition … Low cost oil and gas create a substantial advantage domestically and internationally for the USA. CCUS extends this considerably as the world transitions to a low carbon energy economy.”

“I’m very conscious of the fact that many will read this report as the oil and gas industry saying let’s do CCUS so we can keep on doing oil and gas as usual,” Bordoff responded. “Need to avoid that perception. We heard that from all the independent academics and think tank types involved with putting this chapter together. …I think the credibility of the report will be enhanced if we err on the side of staying away from claims that sound self-serving for the industry.”

“I understand your point about the perception that the remarks regarding low cost oil and gas may look self serving,” Hill responded. “This was genuinely not my intent. It is good to be reminded how others may perceive this—thank you.”

The National Petroleum Council’s page on the final CCUS report notes that of the 300 people tasked with writing the study, “less than 33% are from the oil and natural gas industry.”

What’s Next

The subpoenaed documents, which range from 2015 to 2021, cover an unusual time for oil companies: directly during or after the Exxon Knew investigation, through the Trump years and the early start of the pandemic. As the documents show, oil companies were eager to let the public know that they were working towards climate solutions, moving away from outright denial—while privately pulling the cultural, economic, and political levers of power available to them, including their relationships with universities, to ensure their voices were heard to keep fossil fuels on the table.

Now, many of these companies have reported some of their most profitable earnings to date for the past two years, as the global energy crisis kicked off by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has jacked up oil prices once more. Many oil majors, including BP, have since walked back on their climate commitments. The Biden administration, meanwhile, proved to be more of an ally to oil and gas companies than a foe, keeping up production levels and carving out advantages for favorite solutions like CCUS and hydrogen. Another potential Trump administration—with its heavy emphasis on American energy independence—would only benefit the industry.

Universities are, similarly, in a much different position than they were during the time of this subpoena. Many have faced divestment campaigns from their student bodies in recent years, with some success for activists. In 2022, Princeton agreed to a partial divestment from fossil fuels—but did not agree to divest funding from programs like CMI. Now, an unexpected new wave of student activism around Palestine is gripping college campuses—and forcing the nation’s attention on where universities’ financial allegiances lie. Perhaps it’s time for these universities’ relationships with Big Oil to help focus that spotlight.

This is the first of several deep dives into the new documents we’ll be doing here at Drilled, along with coverage of the May 1st hearing. Come back for more throughout the week!