Daniel Edelman learned the tools of his trade during World War II, serving four years in a United States Army psychological warfare unit that combatted Nazi propaganda. Returning home to New York City after the war, he had a decision to make: Return to his pre-war journalism career, or use his psy-ops skills to make his way in America’s booming post-war economy?

After a brief stint with CBS, he chose the latter, taking a job as a publicist for his brother-in-law’s record label. In 1947 he moved to Chicago to become public relations director for Toni, a hair care company with a popular home permanent kit. While at Toni, Edelman began to combine a bit of lobbying into public relations. Salon owners didn’t love the idea of women giving themselves perms at home, and had mobilized to get do-it-yourself kits banned. Edelman succeeded in convincing various state lawmakers that salon owners were going too far, and none of the proposed bans became law.

Edelman founded his public relations firm in 1952, with Toni as his first client. By 1960 the firm had 25 clients that included household names like Sara Lee, and a second office in New York. By the late 1960s, it was opening offices in New York and overseas.

The R.J. Reynolds tobacco company approached Edelman in 1977 for a proposal to help restore its image and business, in the wake of the 1971 ban on cigarette advertising.

There’s a lot of documentation on the scientists who helped tobacco firms manufacture uncertainty about the health harms of their products. As historians Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway recount in their book Merchants of Doubt, some of these same scientists went on to do similar work for Big Oil, to spin the public on the link between burning fossil fuels and climate change. t But not much has been written about the publicists who helped to craft this strategy, among them Daniel Edelman. A key part of his 1977 proposal to R.J. Reynolds was the idea of creating room for doubt in the cigarettes-and-health debate. “In our judgement, if we can convince the public that there is a real possibility that additional research can produce entirely new insights on health and smoking,” he wrote, “we can improve the industry’s own credibility.”

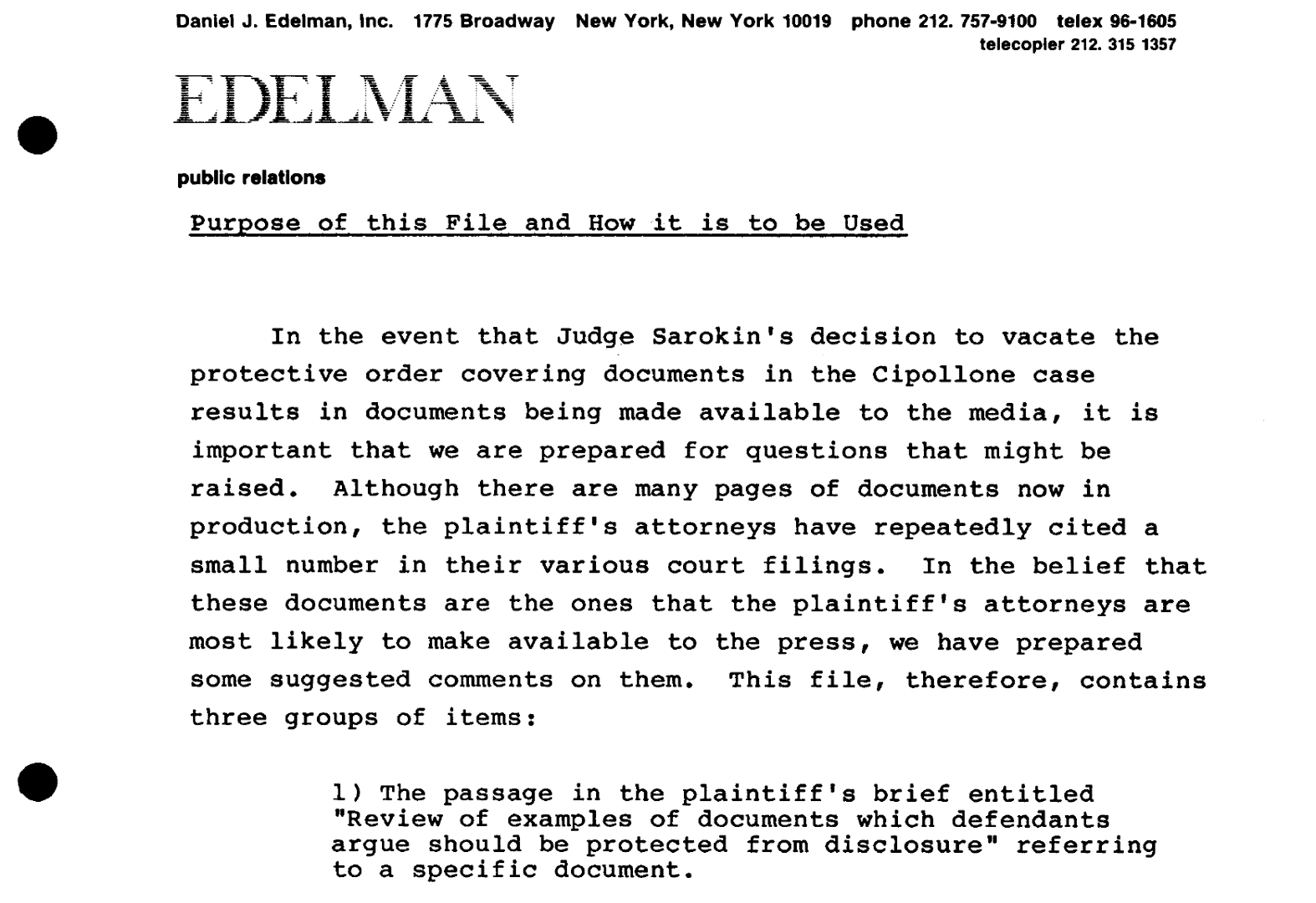

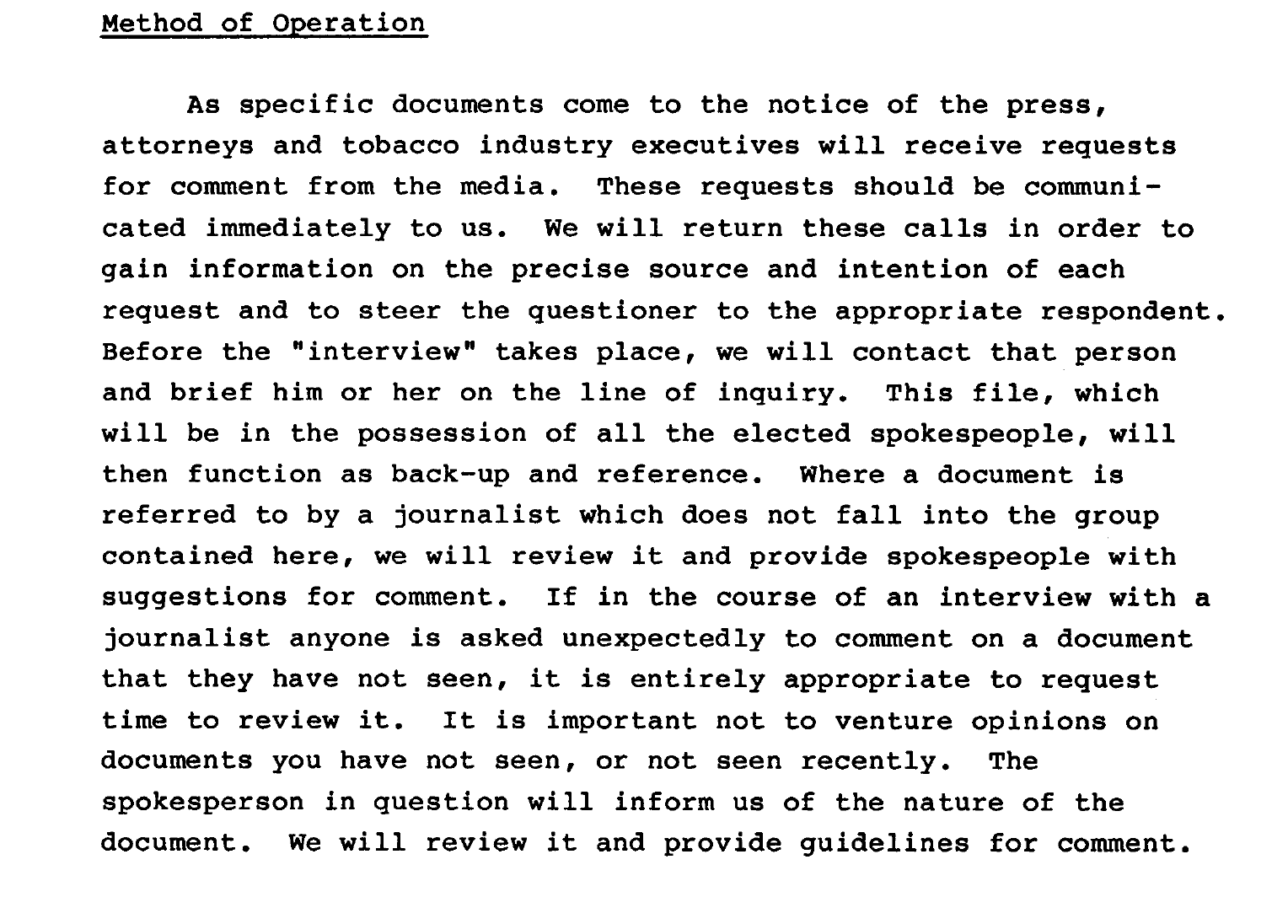

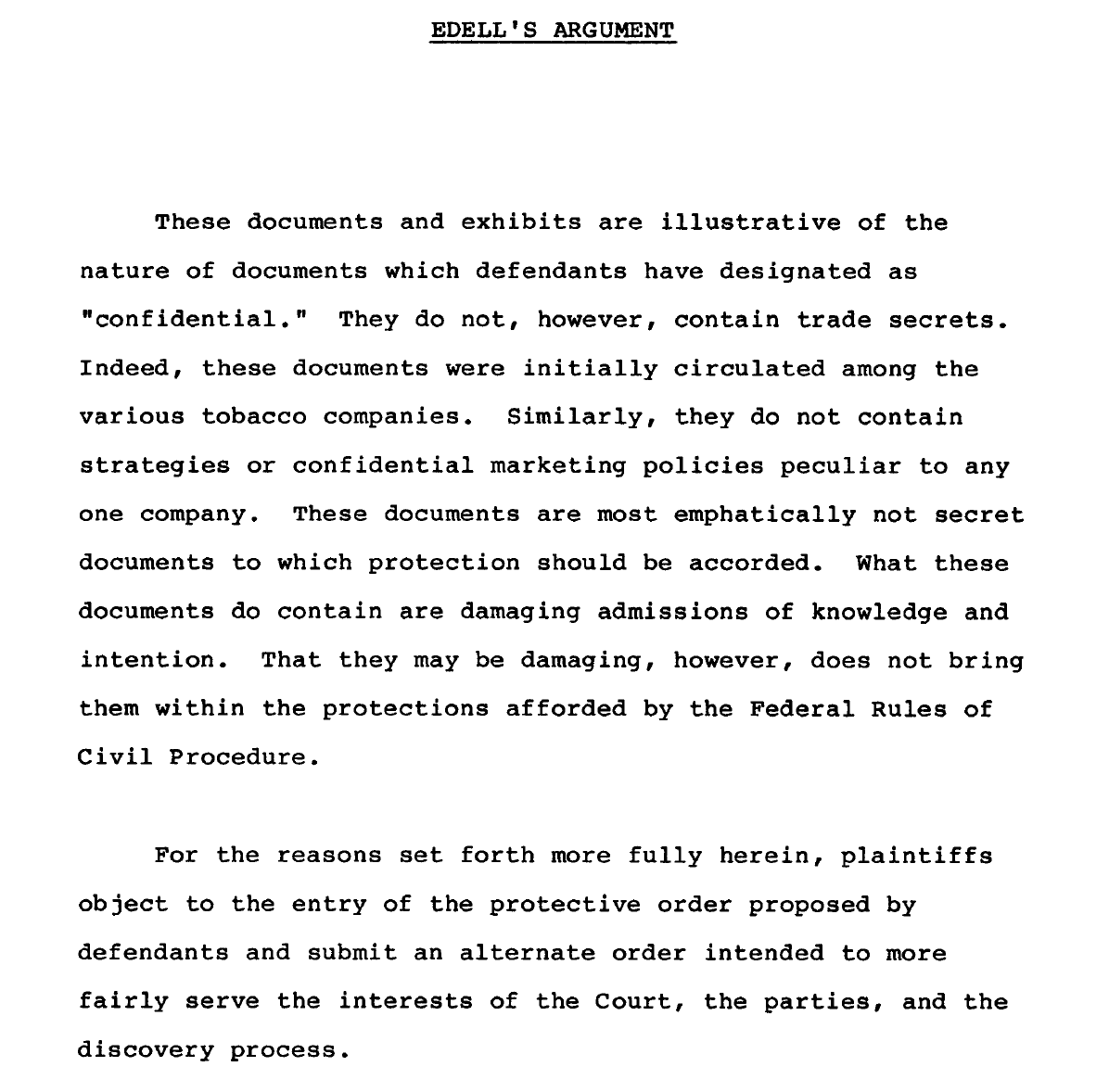

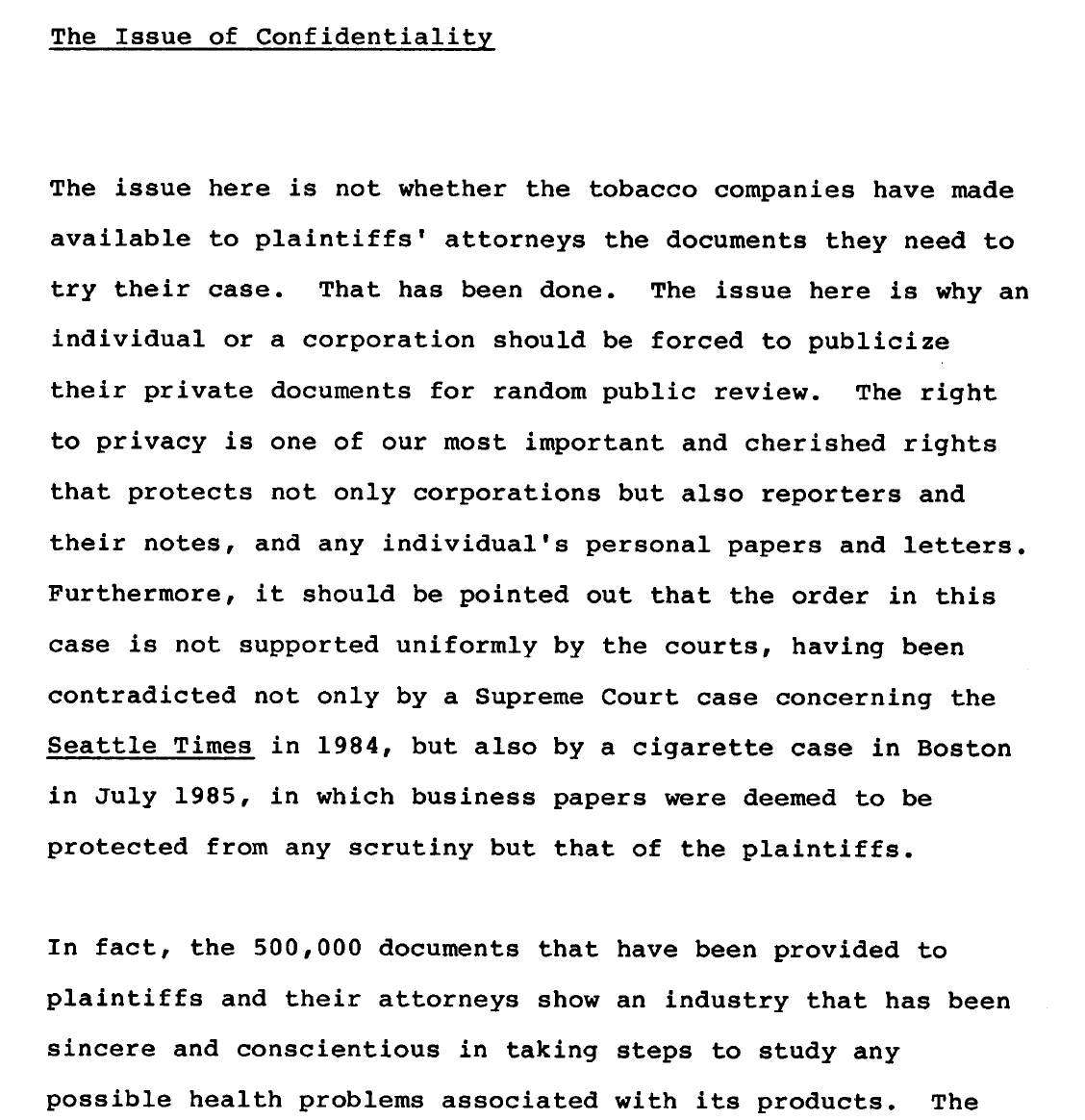

The proposal was a success—Edelman was still advising R.J. Reynolds in 1985, per documents in the Industry Archive at UCSF. In the document highlighted below, for example, an Edelman exec on the account is advising RJR how to handle the hundreds of internal industry documents that had, by that point, become public.

Edelman was also an early proponent and practitioner of “astroturfing”: creating fake grassroots groups, with their funding by industry obscured,, to counter real environmental and public health activism. “Edelman was genius at it,” says Christine Arena, a former Edelman vice president.

Over the past three decades, several such groups have gone on to become major players in confusing the public about climate change.“Fossil fuel industry organizations fund these fake front groups, and they give these fake front groups these perfectly innocuous names, like the ‘California Drivers Alliance’ or the ‘Washington Consumers for Sound Fuel Policy,’” Arena says, which are actually run by the Western States Petroleum Association, which is a top lobbyist for the oil industry.” Another prominent pro-industry group that tries to appear independent, the Western States Petroleum Association, is funded by BP, Shell, Exxon Mobil, and other Big Oil firms, says Arena. “It’s fake activism. It’s corporate money posing as activism. And it’s designed to undo all of the progress that real activism makes.”