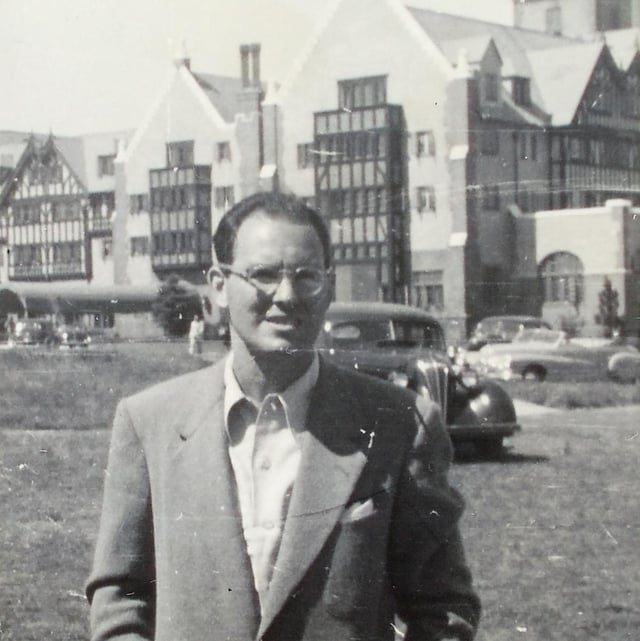

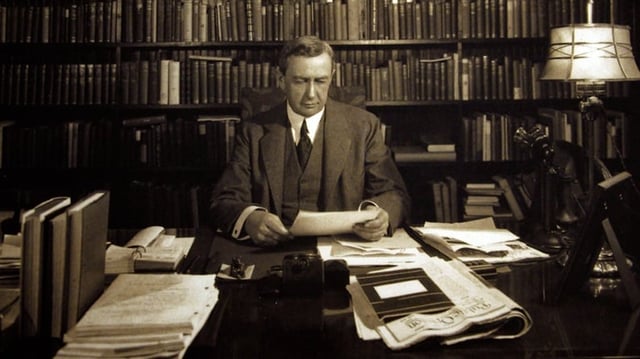

E. Bruce was another behind-the-scenes guru, all aw shucks Southern charm but a master manipulator of the public and the government. An Alabama boy desperate to escape his roots, he spent a brief stint as a reporter at the local newspaper before making his way into politics, first as the press secretary of an Alabama Democrat, where he even wound up helping out on JFK’s campaign.

But his favorite visitors to the Alabama Senator’s office were the corporate lobbyists. His boss had no time for these folks, but Bruce liked the cut of their jib, and the idea that business was a better way to solve problems than policy would ever be.

The chemical lobby wooed him to work for them, making him the very first “environmental information officer” ever, and almost immediately he found himself facing an enormous challenge: beating back the first wave of the environmental movement and “that damn book” Silent Spring. He lost that battle, but learned some lessons, and then went to work for a mining company that sent him off to Indonesia to set up a deal to create the world’s largest copper mine.

When he came back to D.C. in 1972, it was clear that industry had truly been caught flat footed by the environmental movement, and were struggling to regain their footing. Most modern environmental legislation was passed between 1965-1972, and the EPA was established in 1970 to enforce it all. Harrison’s old pals in the chemical industry and at the American Petroleum Institute were losing in this new world, and he was in a perfect position to help them win again—he knew business, he knew government, he knew lobbying and PR, and now he even had foreign relations under his belt. Harrison’s big idea was to combine various industries, unions and government entities together into groups that could get more done and couldn’t be traced to any one company. He created the National Environmental Development Association (NEDA), a vaguely pro-environment-sounding name that was actually a coalition of chemical, mining, oil & gas, and ag companies, along with industry-friendly politicians and unions, really anyone who had a bone to pick with the new environmental regulations.

Harrison made NEDA the first client of his new PR firm, Harrison & Associates, which he co-founded with his new wife, Patricia. Patricia was very much an equal partner in the firm, and very involved in the NEDA account. Years later she would work as the co-chair of the Republican National Committee and as a staffer in George W. Bush's state department. Her official State Department bio read, “As a founding partner of E. Bruce Harrison Company, among the country’s top ten owner-managed public affairs firms prior to its sale in 1996, she created and directed programs in the public interest comprising diverse stakeholder groups, including the National Environmental Development Association, a partnership of labor, agriculture and industry working for better environmental solutions together.”

They would monitor all proposed environmental policy, brief NEDA members, craft messaging around it and make sure the press had the industry viewpoint on things. They also lobbied members of Congress, and even testified before committees about the economic harm any new environmental regulation would do. Most importantly, NEDA helped to push the idea of balance and necessary trade-offs between protecting health and the environment on one hand, and economic growth on the other. At the same time, the global oil crisis had Americans looking for new forms of domestic energy, which not only spurred research into solar, but also into drilling in previously protected areas. Americans who had been getting into the whole clean air, clean water thing were suddenly rationing gas and getting very worried about losing the American way of life. Meanwhile, research scientists at oil companies and universities were stacking up evidence about a new, far deadlier sort of environmental impact for industry to worry about: the greenhouse effect.

In the 1980s the oil crisis became a glut and oil companies were facing the dual threat of cratering prices and looming environmental regulations. But Harrison and his compatriots had done a fantastic job by this point convincing Americans that regulation was bad for the economy and that the American way of life needed to be protected at all costs, especially with those commie bastards gaining power in Russia and China. 1989, as the world was growing increasingly concerned about global warming and regulation seemed more and more likely, Harrison brought auto makers, manufacturers, utilities, oil, gas, and coal companies together to figure out a strategy. He called it The Global Climate Coalition. And the first thing he did was get its members into the international climate meetings of scientists and politicians that were just starting. GCC members, and Harrison himself, were involved in shaping the UN Framework on Climate Change. They were there weighing in on the very first report from global climate scientists, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report in 1992. They were at the very first international climate conference, the Rio Earth Summit, pushing world leaders to embrace the idea that there was plenty of time to act on climate change, that we shouldn’t risk economic hardship to do it, and that in fact business could be trusted to do this work voluntarily. The group spent about $1 million a year from 1989-1997, the lead-up to Kyoto, in advertising (and $13 million in 1997, as the climate summit drew near). The group spent $63 million in campaign contributions during the 1990s.

By this point, Harrison had sold his firm to PR giant Ruder Finn because his wife was elected to co-chair the Republican National Committee and help steer Bush to victory. Harrison stayed on with Ruder Finn to advise on various clients, including his creation the GCC. Bush won, of course, and within weeks of his inauguration had pulled the U.S. out of Kyoto, using Harrison’s favorite argument, that acting on climate change would unnecessarily harm the U.S. economy. In a meeting with representatives from the GCC shortly after, Bush’s State Department told the group that the administration had pulled out of Kyoto at their suggestion, and wondered if the GCC had any ideas for climate policies they would support..

Patricia Harrison was rewarded for her election help with a plum assignment in that very same Bush State Department. Bruce went on to create the whole sustainable business ecosystem, earning him the nickname, “the godfather of greenwashing,” which he hated. He eventually became a professor at Georgetown and Patricia was hired as the President of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the public-private partnership that oversees government funding of public media in the U.S. Some critics voiced concern at the time that her time as RNC co-chair would make her too biased for the position. No one knew that she had also helped create the myth of “clean coal,” or that she and her husband were, as one sociologist puts it, “the intellectual parents of climate denial.” Patricia Harrison remains in that position today.

E. Bruce Harrison died in January 2021, and was eulogized by national papers as a “pioneer in environmental communications.”