There are two types of PR guys, the ones who make themselves a central character in the story and the ones who work their magic quietly behind the scenes. Earl Newsom was the latter sort to the extreme. His name only really comes up in the context of other PR legends talking about what a genius he was. But while he kept an extremely low profile, Newsom was possibly the most influential PR guy of the 20th century, working for corporate giants like Ford, GM, Campbell's Soup, Standard Oil of New Jersey (which later became Exxon), and many more.

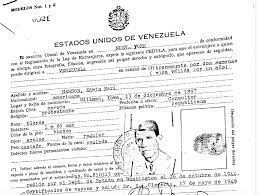

Newsom was born in Wellman, Iowa, and graduated from Oberlin College in 1921. He took time off of college to serve as a Navy pilot in WWI. His approach to the job was not at all about press releases or talking to journalists, instead he really focused on truly managing the relationship between a company or an industry and the public. He was a trusted advisor to CEOs, helping them navigate crises and keep a constant, close read on the public. Newsom also collaborated often with Elmo Roper, who pioneered market research and polling. From the late 1930s onward, Roper based the majority of his PR plans on polling reports from Roper.

Standard Oil of New Jersey

Earl Newsom worked for Standard Oil of New Jersey, which eventually became Exxon, from the early 1940s til he retired in the mid-1960s. He managed every aspect of the company's public persona, from seemingly inconsequential decisions like whether or not a VP should accept an award from a PR college for his work on education (Newsom said no, lest people think Standard's investments in universities were just a PR stunt) to the company's approach to developing oil fields in South America and the Middle East to cross-industry strategies for shaping how Americans think about the economy. One of the most fascinating documents Newsom left behind was a strategy document from early in the year in 1945. WWII was coming to a close, and Newsom was concerned—not that the Allies would lose, or that the companies he worked for would have to find new revenue streams once wartime purchasing ended, but that Americans had grown so used to the government taking care of them that they might turn away from the benefits of free enterprise. At the time, Newsom was working for Standard Oil of New Jersey, Ford, and GM, but the plan included non-clients too, it was an all-hands-on-deck moment for industry.

"Next to crushing the Axis, and avoiding runaway inflation while we are doing it, the most important problem confronting us is to keep the American people convinced of the intrinsic social and economic worth of the free enterprise system," he wrote. "And of its superiority over statism, so that the people will be determined to remove unnecessary governmental controls and reestablish competitive, democratic, free enterprise capitalism when the war is won."

"There is grave danger that many millions of Americans will be given the impression that the free enterprise system is full of gross abuses and dishonesties," he continued. "That private business has put and is putting its own narrow selfish, financial interests above patriotism; that the free enterprise system has outlived its usefulness; and that all-encompassing state-imposed economic planning is better for the people than the system of competitive free enterprise."

We've gathered hundreds of pages of documents from Newsom's time with Standard Oil of New Jersey, available on our Document Cloud here.

General Motors

Newsom also worked for General Motors in the 1960s during a particularly tough time for the company, when it was dealing with the fallout of Ralph Nader's seminal 1965 book, Unsafe At Any Speed. More so than the book itself, GM faced public backlash and a Senate investigation over its handling of the book, which included gathering opposition research on Nader and even trying to entrap him with young women. Newsom counseled GM's executives through the Senate hearing and apology for the Nader debacle, and through various skirmishes with labor unions over the years.

Ford

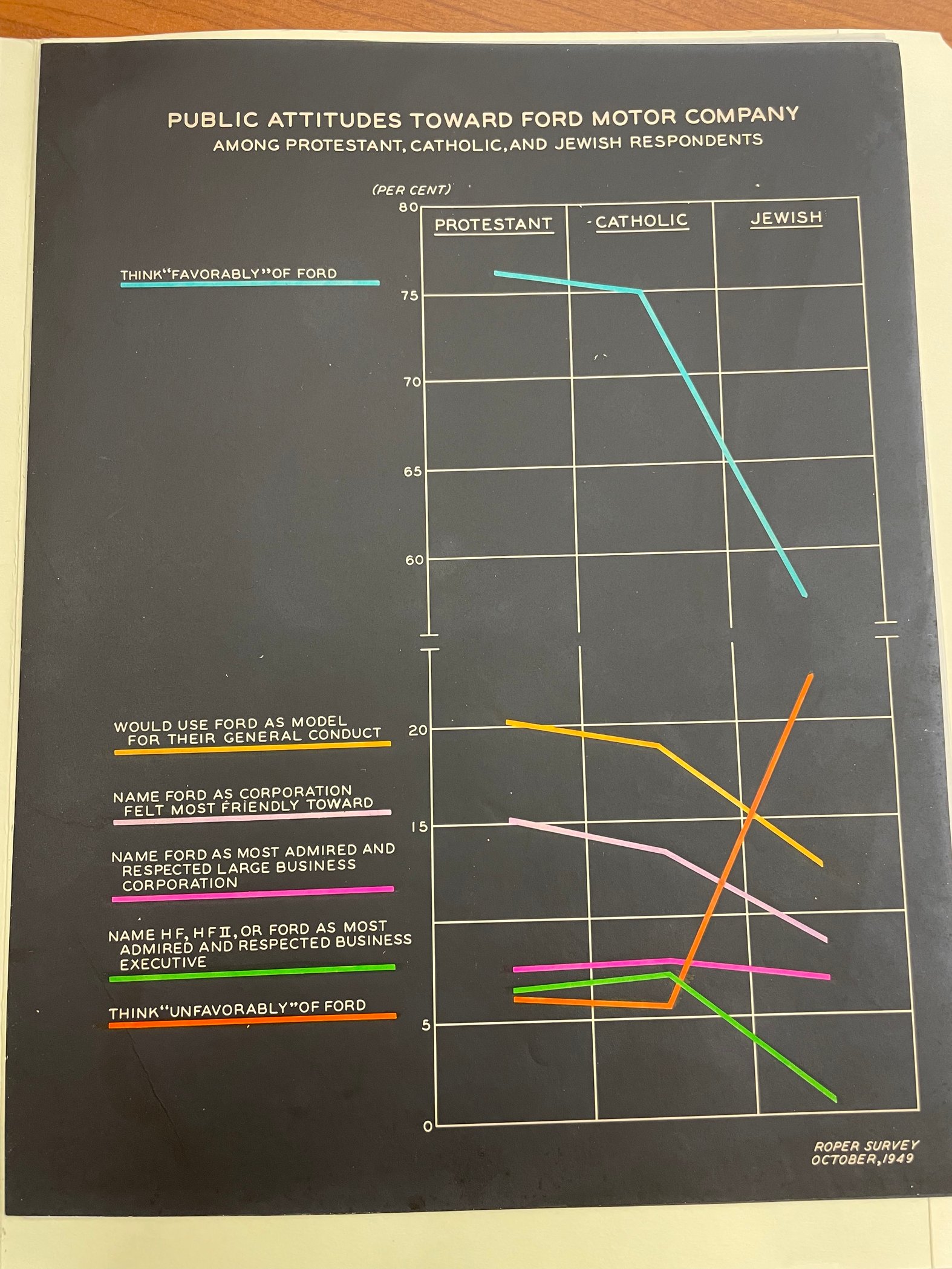

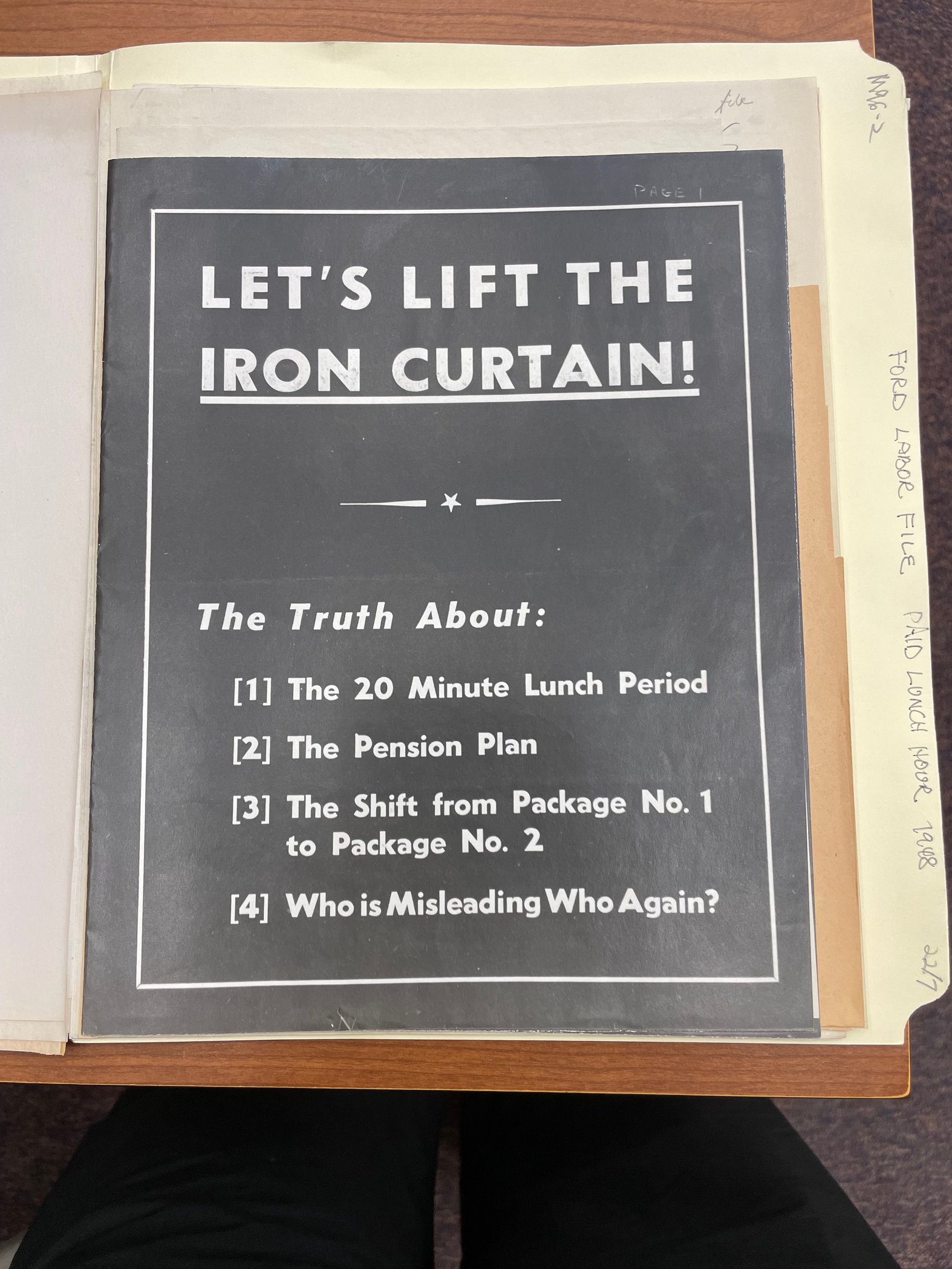

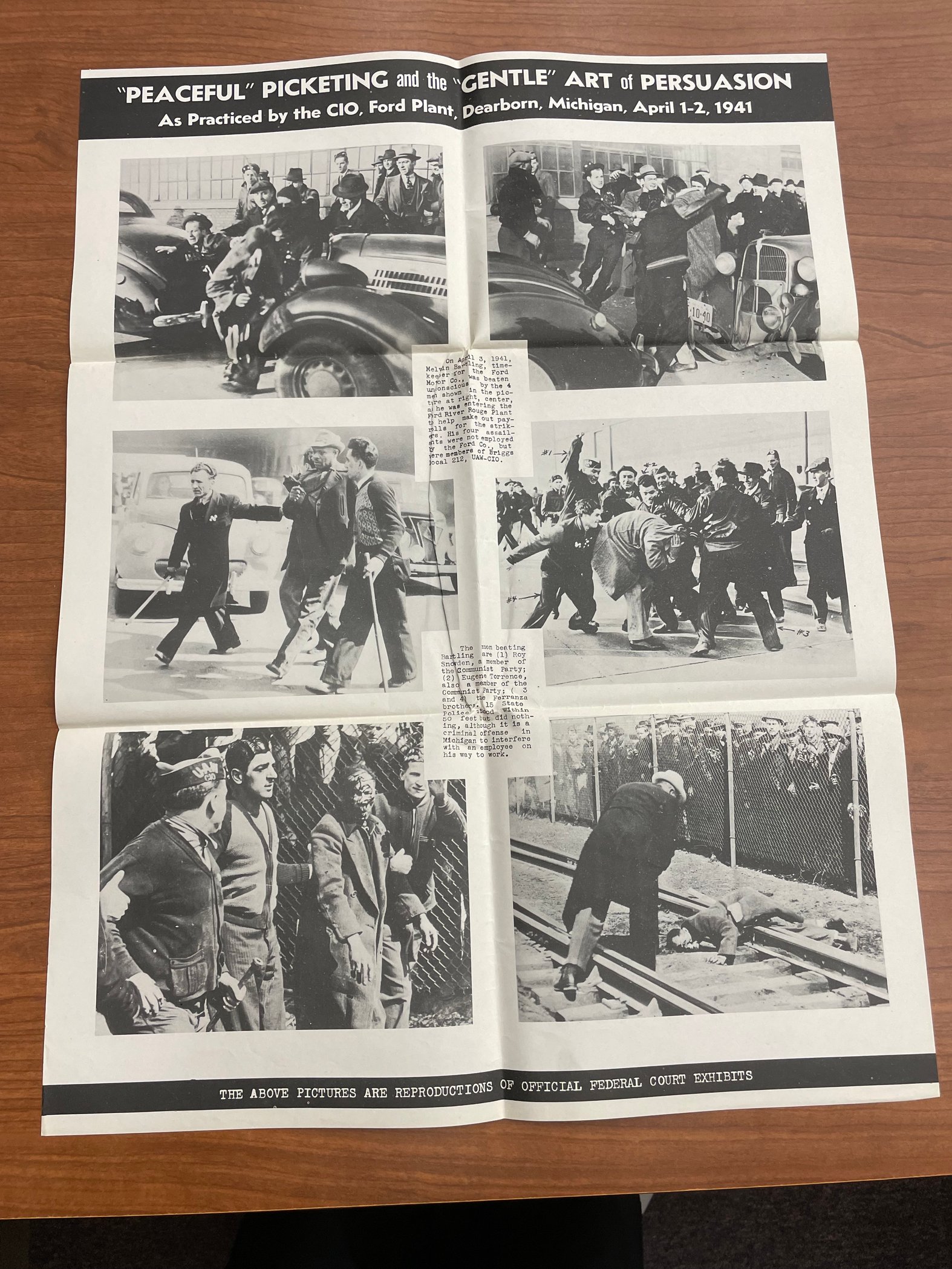

Newsom's longtime friend and collaborator the pollster Elmo Roper started pushing Ford to hire Newsom in the 40s and initially Newsom actually said he was too busy. He thought Henry Ford and his son Edsel would be too tough to manage. This is where you really see how different Newsom was from most of his compatriots in the field. He really saw himself as a close advisor to CEOs, managing every aspect of their relationship with the public. And he couldn't do that—wouldn't do it—with a difficult CEO. But in 1945, Newsom had a meeting with Henry Ford that convinced him; he set about turning the elder Ford into what he called "an industrial statesman," giving speeches, meeting with politicians, acting as a sort of ambassador for American industry to both the U.S. public and the world. Newsom counseled Ford through the highly controversial move of pulling the paid lunch period post-war, crafting and executing an internal communications strategy that painted the company as benevolent and fair, the idea of paid lunch as Communist, and the striking employees as criminals.

Eli Lilly

Newsom was one of the first publicists to work with the pharmaceutical industry, advising Eli Lilly for years, with a focus on pushing the idea that private enterprise and pharma profits were the key to innovation and life-saving miracles. Newsom and Lilly's other PR firm, Hill & Knowlton, would coordinate various campaigns and press pushes through the pharma trade group, the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association.