From war to cigarettes, guns to GMOs to global warming, there are really only a handful of techniques that have been deployed over the past 125 years or so to shape and control public opinion, to make the masses an unwitting tool of the few and powerful. There's quite a bit of panic these days about disinformation and fake news, and with it a sense that this is a new problem, created by Gamergate or Trump or Steve Bannon or social media. The reality is that the techniques being used today are a century old; what's new is the distribution mechanisms, the relative ease of creating a platform and spreading whatever story you want far and wide. That part is scary, and most experts in the space say the solution is two-fold: media literacy and regulation. We're focused on the first bit, because once you know what the tried-and-true disinformation techniques are, and how they've been deployed, it's easy to spot them and thus disarm much of their power.

Following is a glossary of techniques based on more than 20 years of investigative journalism from Amy Westervelt, and pulling from the work of several academic researchers as well, including Melissa Aronczyk at Rutgers University, Timmons Roberts and Robert Brulle at Brown University, Riley Dunlap at Oklahoma State University, Aaron McCright at Michigan State University, Naomi Oreskes and Geoffrey Supran at Harvard University, Leah Stokes at University of California at Santa Barbara, and Ben Franta at Stanford University, many of whom are also members of the excellent Climate Social Science Network.

We also owe a debt of gratitude to researchers not affiliated with any academic institutions, including Kert Davies and Dan Zegart at the Climate Investigations Center, Nick Surgey at Documented, and Lisa Graves at True North Research. We are very open to suggestions, additions, edits and critiques. Please send them to amy at drilled dot media.

Astroturfing

Astroturfing refers to groups that appear to be "grassroots" but are in fact front groups created and paid for by either a company or a PR firm acting on behalf of a company or industry.

Industries that use or have used it: Chemicals, food, oil, pharmaceuticals, tobacco.

Corporate Personhood

The idea that corporations are people and thus deserving of praise when they behave well, and a break when they 'mess up' (because it was probably just an accident anyway, geez, people are fallible and companies are just groups of people). Companies are, in fact, groups of people. They are not, however, people themselves. In fact they are legally required to behave very differently than people, which is why giving them the rights and benefits of people lends them an enormous amount of power. The most recent expansion of corporate personhood rights came on the heels of the Citizens United Supreme Court ruling, which enabled corporations to donate as much as they want to political groups and campaigns without disclosing it. But oil companies are arguing right now in court to expand corporate free speech rights even further. In some 30-odd climate liability and fraud cases oil company lawyers are arguing that anything their clients have ever said about climate change was in service of shaping policy and thus is protected political speech, even if it was knowingly and intentionally misleading.

Industries that use or have used it: All of them

Examples:

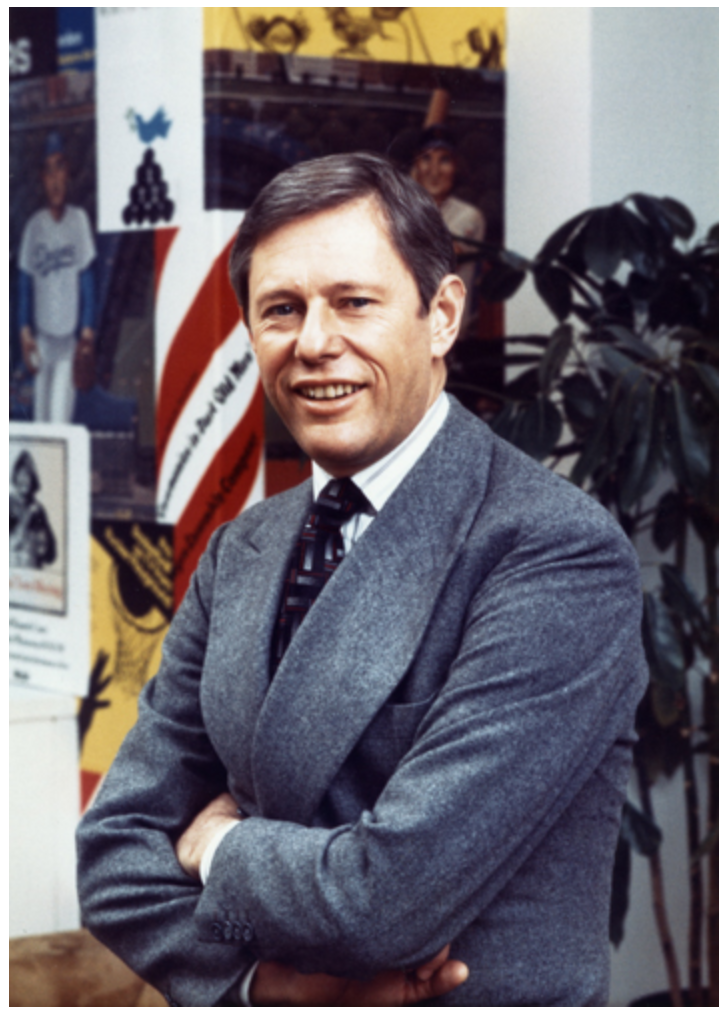

Corporate Social Responsibility

The idea that Corporate Social Responsibility is a PR tactic is a tough pill to swallow. There are companies that invest in the communities in which they operate, that track and try to improve their impact on the world. But the modern conception of corporate social responsibility was more of an offshoot of the corporate personhood movement, and it was created for the same reason most of these techniques were created: to avoid government regulation. One of the godfathers of this particular approach to corporate social responsibility and business sustainability was E. Bruce Harrison, and Harrison's idea was that if you could convince the public and politicians that business could solve its own problems—could be both more responsible and more innovative if left to its own devices—the political will for regulation would evaporate. Harrison started his career working for the chemical industry to fight the impact of Rachel Carson's blockbuster book Silent Spring; he lost that battle, but he learned several important lessons that he went on to apply to work for the mining industry, automotive and manufacturing industries, tobacco, and oil. In the 1980s and 90s he worked on behalf of oil, automotive and manufacturing clients to push the idea that industry was already working to combat the greenhouse effect and could be trusted to manage emissions and any necessary energy transition themselves. But Harrison is far from the only practitioner of this tactic, and it spans every industry.

Industries that use or have used it: All of them

Examples:

Creative Confrontation

“Fight back--the best defense is a good offense.” This was Herb Schmertz's key piece of advice to all businesspeople about dealing with the media. Schmertz preached a combative strategy for corporate public relations, which he had honed as a political operative in D.C. He urged businesspeople to create the illusion of access, playing hard to get with reporters requesting information or interviews, and to bring the hammer down hard on journalists, editors, and outlets who don't play ball.

Industries that use or have used it: Alcohol, automotive, food, oil, tobacco

Examples:

Schmertz’s account of a meeting with the Wall Street Journal in the early 1980s.

Schmertz on the art of “creative confrontation” in his book

Crisis Actors

Like many of this tactics the "crisis actors" narrative has been used both by industry and in the political sphere. It refers to the tactic of accusing any group of protestors or critics of one's actions or industry of being paid actors.

Industries that use or have used it: Food, guns, oil, tobacco

Examples:

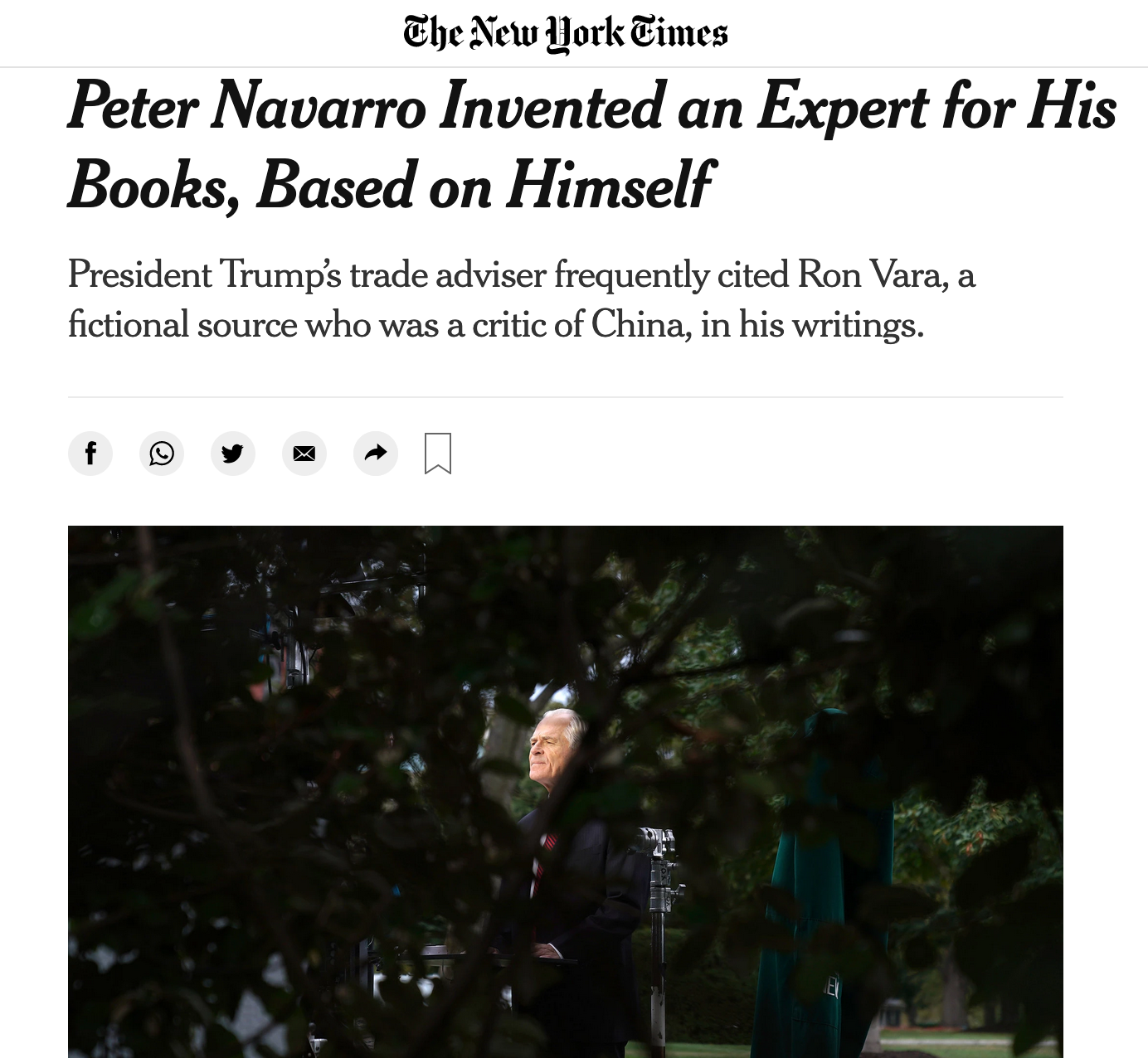

Fake Experts (Fauxperts)

Of all the techniques in this glossary, this is probably the most used and the most insidious. And the most problematic given the current rampant distrust of experts in the U.S. It's a technique that's been deployed since the very early days of the PR industry. Ivy Lee started doing it for the railroad companies even before he started working for Standard Oil and the Rockefellers. By the time Edward Bernays got his firm going, he had experts on retainer, ready to jump in and help legitimize his clients as needed. It's only continued from there, often bleeding into science denial (more on that particular flavor below).

Industries that use or have used it: All of them

Examples:

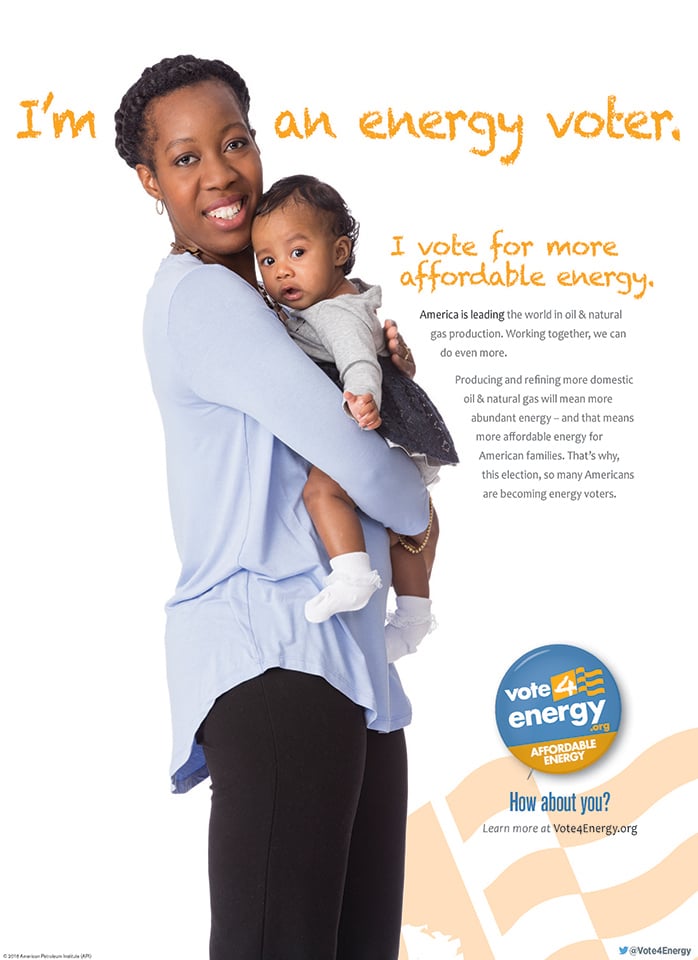

Individualizing Systemic Problems

This tactic works particularly well in the U.S. where individualism is a core social value. Waste becomes a littering problem, car safety becomes a driving problem, and so forth. It's a handy way for an industry or company to acknowledge a problem and the need to do something about it while shifting the responsibility for both creating and solving the problem onto individual consumers.

Industries that use or have used it: Apparel, automotive, food & beverage, oil, pharma, tobacco

In the 1970s, food and beverage packaging companies that were worried about government regulation on packaging crafted a campaign to place the responsibility for litter with consumers instead, including an Italian American actor dressed as a Native man crying over all the litter in the rivers.

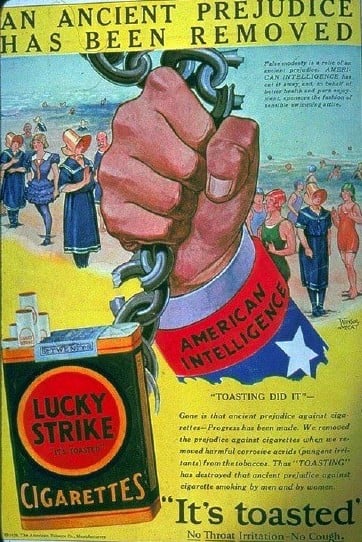

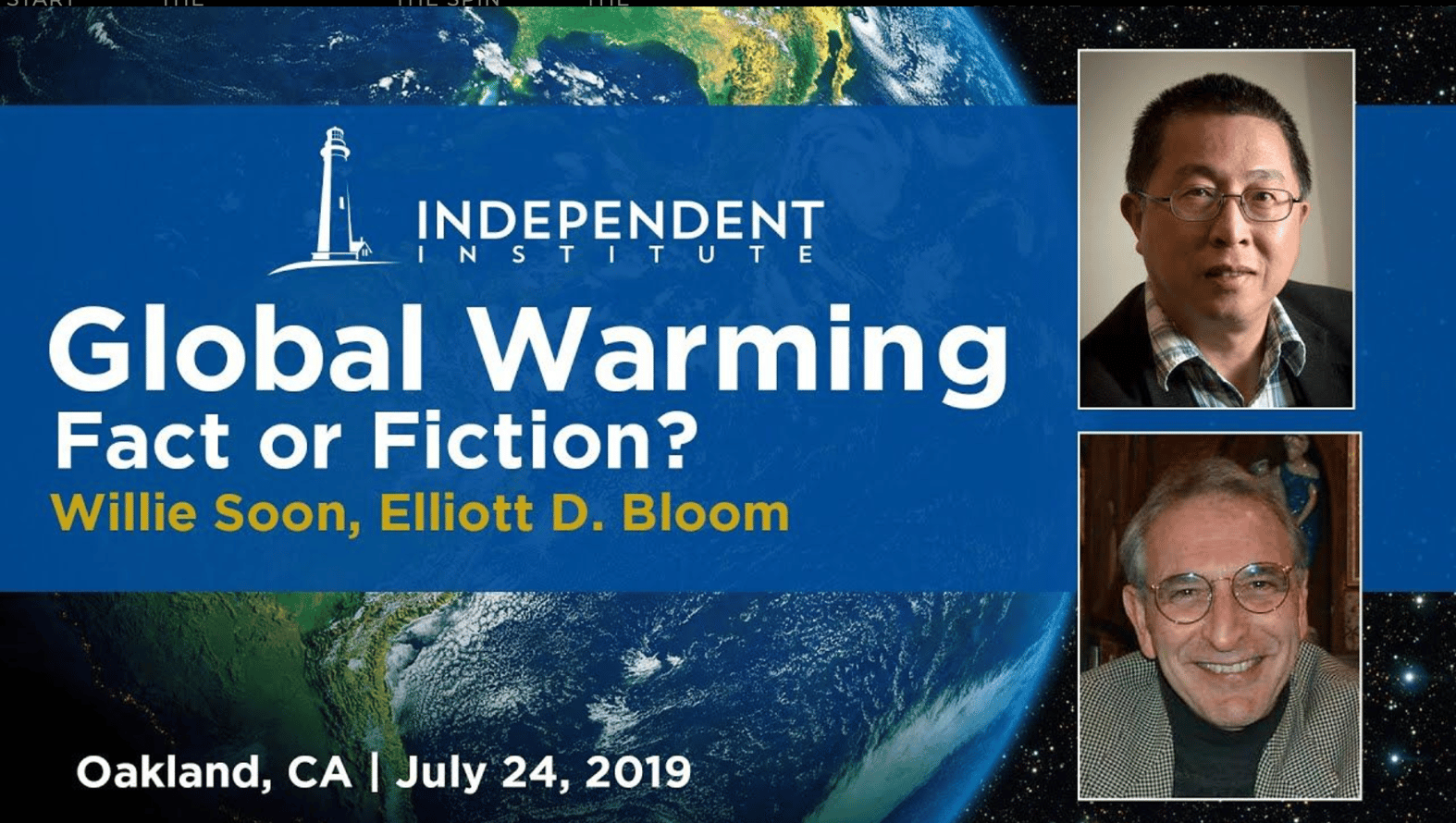

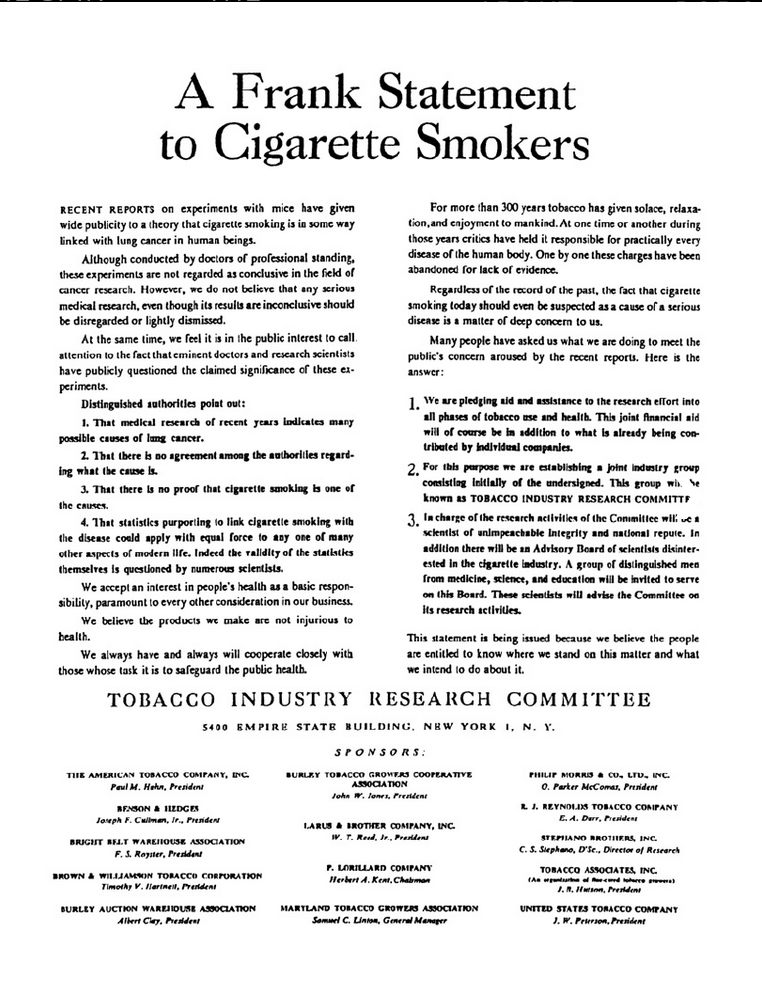

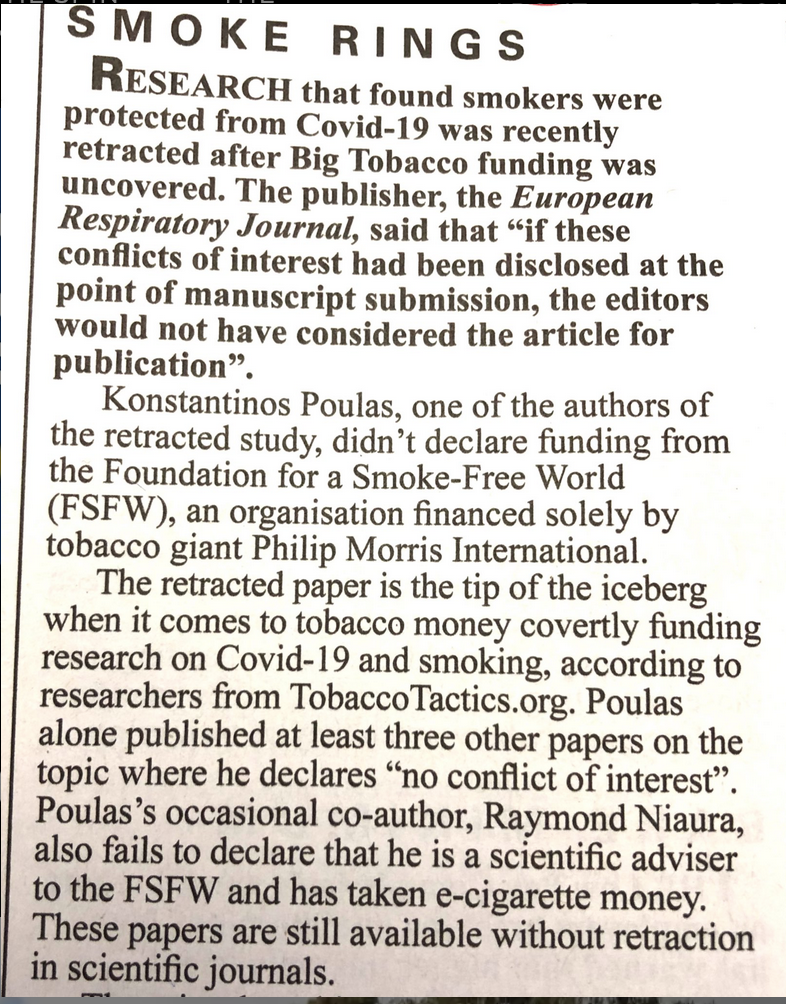

Science Denial

As Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway covered extensively in their book Merchants of Doubt, and Oreskes and Geoffrey Supran have continued to highlight in their work at Harvard, we've seen the exact same sort of science denial with smoking, climate change, and now Covid-19. Oreskes even found some of the specific scientists who worked first for tobacco and then for oil. But there was something else at play too: science denial grew out of the long-standing practice of fake experts, expert bureaus, and research centers, pioneered by Ivy Lee and deployed by every generation of PR experts, on behalf of multiple experts. There are a few different forms science denial takes: flat out denial (the Earth is not warming), deflection (the Earth is warming, but it's not us causing it, it's volcanoes!), and delay (yes it's a problem, but we have plenty of time to deal with it).

Industries that use or have used it: Coal, food, guns, oil, tobacco

Sponsored Content

People may have been doing some form of sponsored content or another (John Hill was paying a freelance journalist to write op-eds friendly to his client, for example), but no one came close to the entire sponcon system Herb Schmertz created for Mobil. Sponsored content is exactly what it sounds like, content a company sponsors. It's generally labeled, but a lot of viewers and readers miss that part. Sponcon can include everything from advertorials to placed op-eds to underwritten film, TV, and radio programs.

Industries that use or have used it: All of them

Examples:

Attack the Messenger

When all else fails, or often before even trying anything else, the oldest trick in the book is to attack the messenger. Ivy Lee, the world's first publicist, liked to blame most of his clients' labor problems on union organizer Mother Jones. In the case of the 1914 Ludlow miners' strike, not only did he accuse Mother Jones of organizing the strike and bringing in paid protestors, he also threw in that the 80-year-old was running a brothel nearby (a wild and bizarre lie). Later, E. Bruce Harrison would throw every possible insult and accusation at Silent Spring author Rachel Carson, car companies surveilled and tried to entrap Ralph Nader, fossil fuel companies would attack the credibility and integrity of climate scientists, the list goes on and on.

Industriest that have used it: All of them

Examples:

Get ‘Em While They’re Young

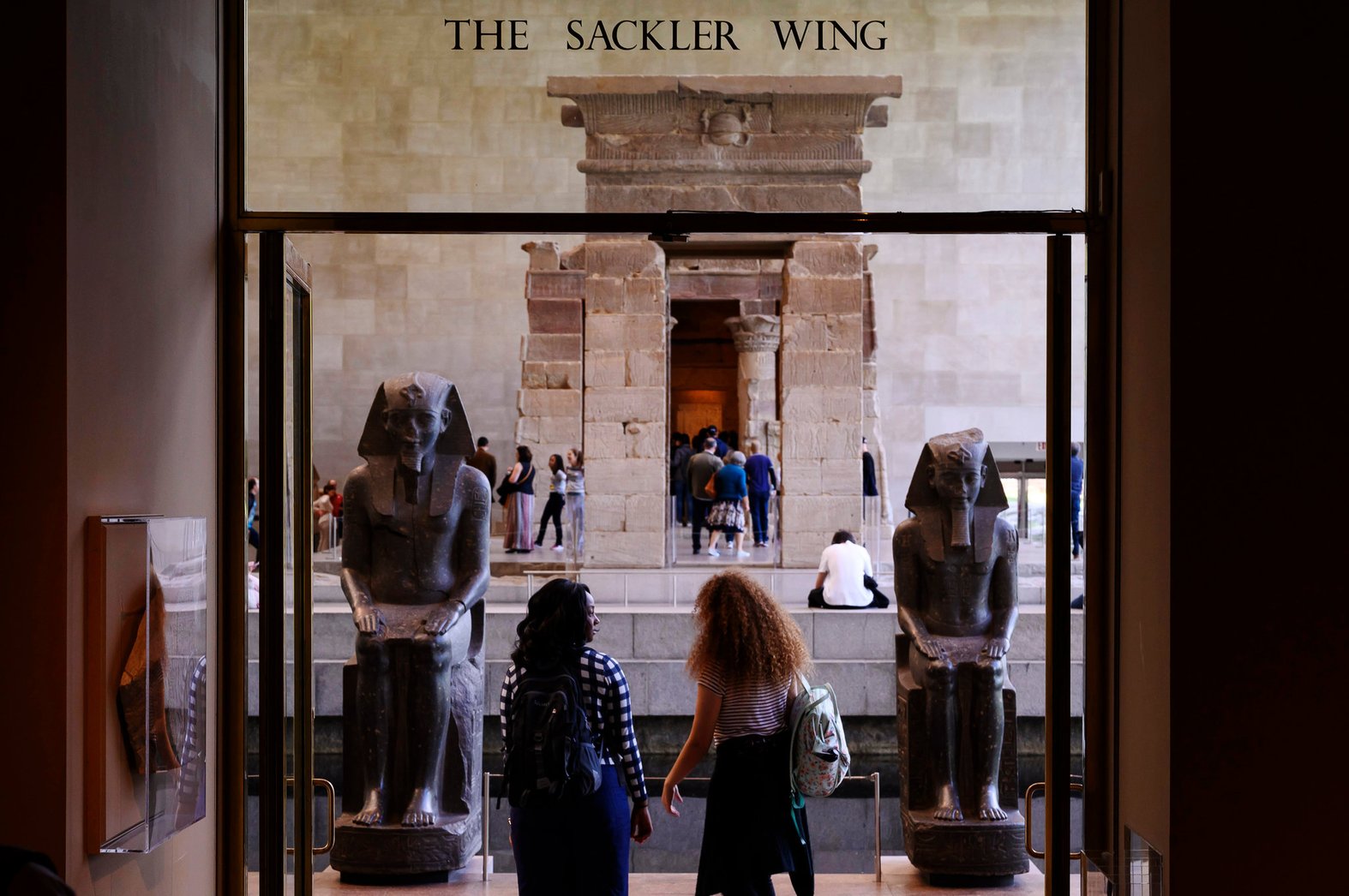

Back in the 1940s and 1950s, American companies began to realize that the best way to shape the minds of the public, was to start as early as possible. Industries targeted teachers groups and universities, some with a focus on shaping how Americans understood the economy, others focused on how Americans understood science or civics. In the early 1950s an important change to the tax code opened up the floodgates for corporate investments in American universities—it made corporate donations to universities a write-off. But as Standard Oil of New Jersey (now ExxonMobil) VP Frank Abrams told anyone who would listen back then, the benefit to companies wasn't in write-offs, it was in unparalleled influence on the next generation of American elites.

Industries that have used it: All of them

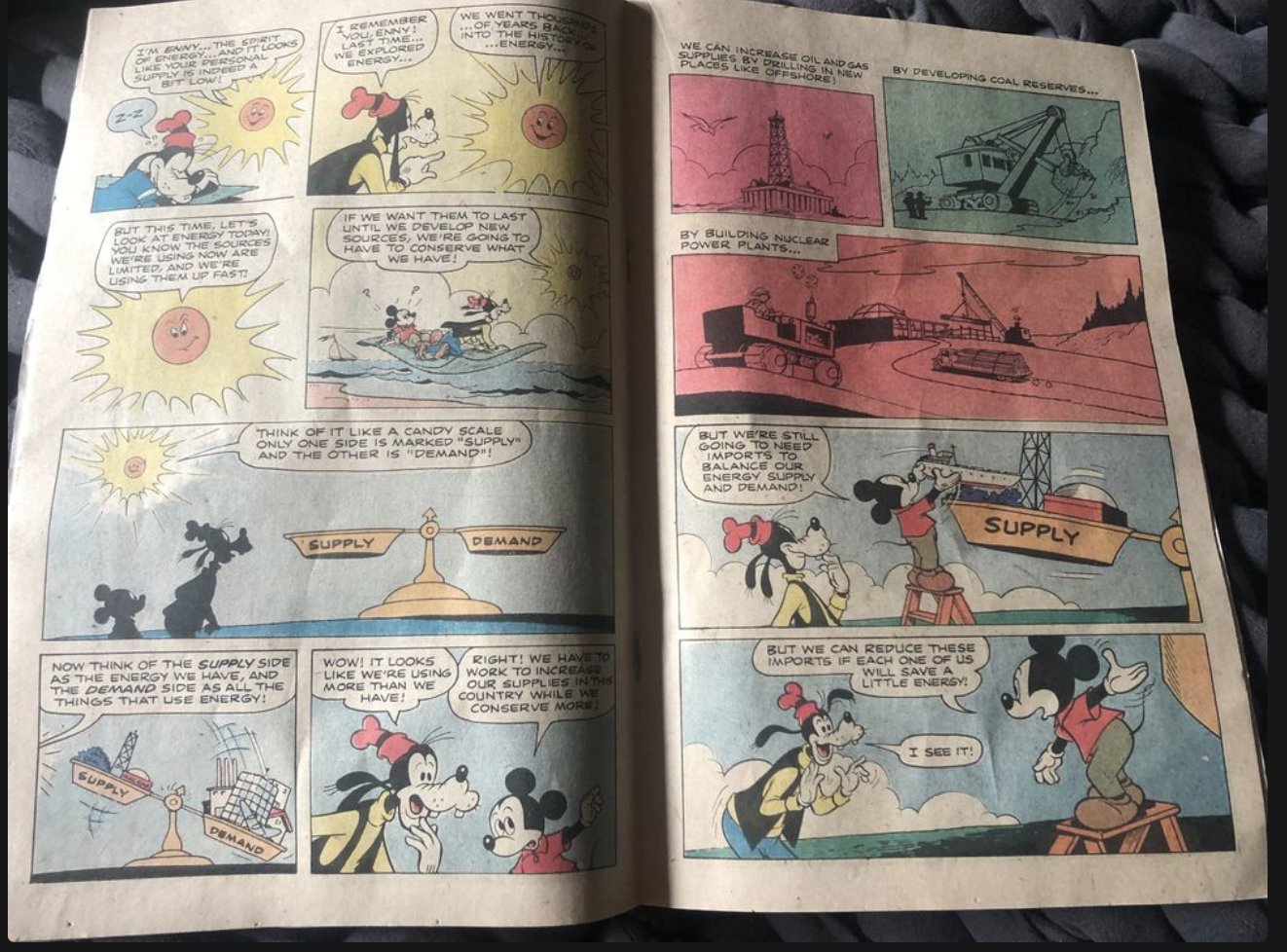

Exxon’s Disney comics about how energy works went along with a sponsored ride at Epcot when it first opened, teaching kids everything they needed to know about the “future of energy,” which of course included