This story is co-published with the Center for Media and Democracy.

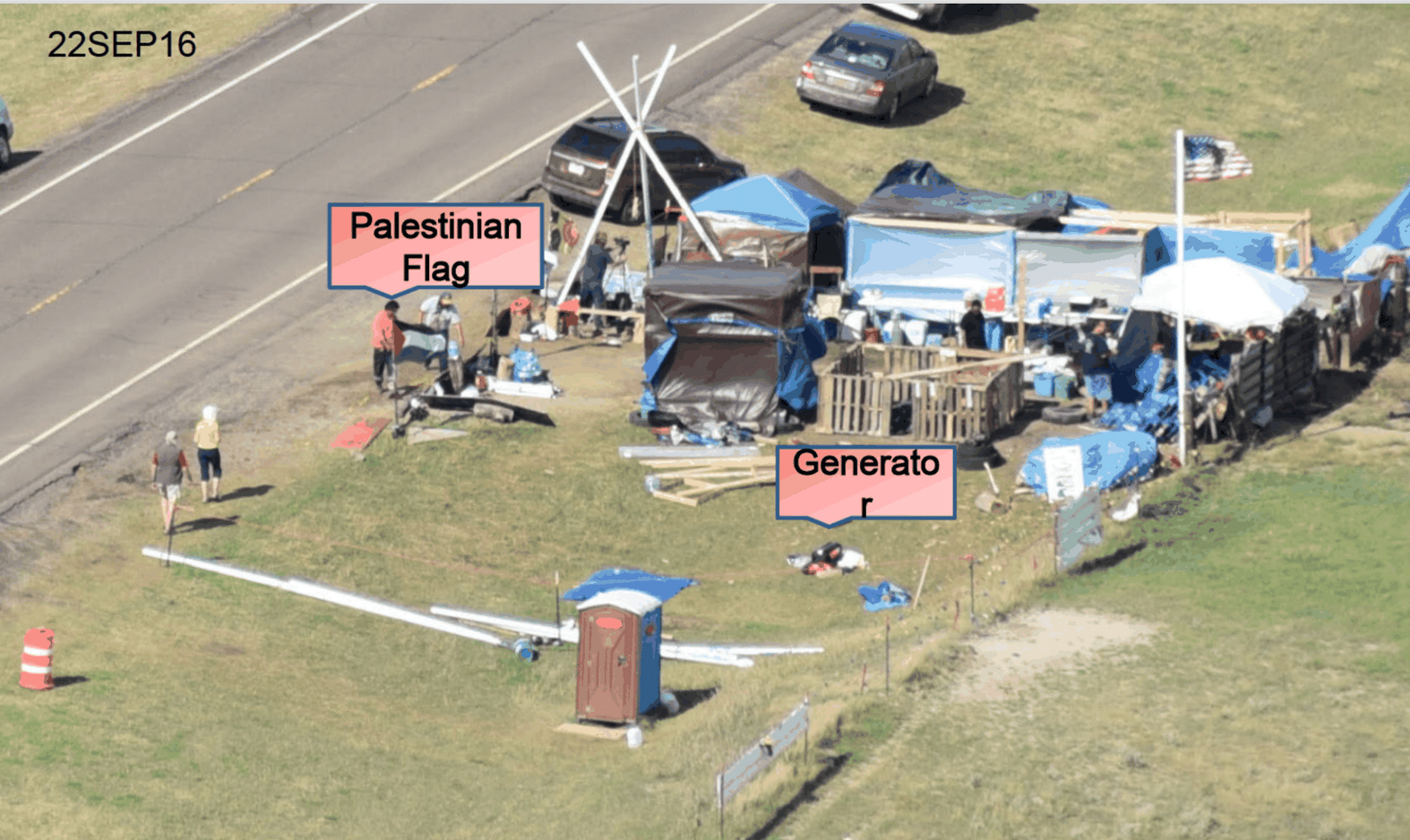

As soon as a single Palestinian activist showed up at an anti-Dakota Access Pipeline camp on the edge of the Standing Rock reservation in 2016, intelligence analysts for the mercenary security firm TigerSwan were on alert. The analysts, who worked for the pipeline parent company Energy Transfer, confirmed via aerial surveillance that a Palestinian flag was flying above the camp, according to internal records obtained via a public records request and reviewed with support from the Center for Media and Democracy.

The Standing Rock movement was fast becoming one of the most important environmental and Indigenous uprisings of the past 50 years. For TigerSwan, keeping its contract meant convincing Energy Transfer that danger was everywhere. The security firm told its client that Palestinians meant an “Islamic” presence and the possibility of “terrorist type tactics.”

“It’s part of the dehumanization of my people and it directly enables the genocide that we’re witnessing now right now. It’s totally built on racism,” said Haithem El-Zabri, the Palestinian activist that TigerSwan first noticed at Standing Rock. “It’s not limited to a security company — it’s common across the board of government agencies.”

By being at Standing Rock, El-Zabri and other Palestinian activists took on the risk of being subjected to fossil fuel industry surveillance. Now, as historic antiwar protests arise across the U.S., the roles have been reversed, with environmental and Indigenous activists standing in defense of Palestinians. In this case, land defenders of all stripes will absorb the sweeping criminalization of the Palestinian cause being pushed by advocates for Israel.

Universities as well as federal and local policymakers are cracking down on the movement against Israel’s war on Gaza. In recent weeks, after students established pro-Palestine encampments and sit-ins at over 95 schools, according to The Appeal, administrators suspended numerous students and called in the police to arrest more than 2200 campus activists, faculty and bystanders, often violently. In the months leading up to the uprisings, state and federal policymakers began introducing “anti-terrorism” bills that stand to erode civil liberties and alter the landscape for protest and dissent far beyond the American antiwar movement—a playbook we’ve seen in countries around the world.

The recent history of environmental activism in the U.S. shows that the repressive policies being advanced now will have repercussions far beyond a single social movement — and that they’re likely to hit climate and land defenders particularly hard. A whole generation of young environmental activists, who are increasingly organizing in solidarity with the Palestinian liberation movement, and against what the International Court of Justice has called a plausible genocide in Gaza — is poised to be recast by proponents of Israel as supporters of terrorism and hate. At the same time, the university-sanctioned arrests and evictions of students are bound to be radicalizing experiences that will indelibly shape future social movements of all stripes.

We’re already seeing the start of this reframing. The youth-led Sunrise movement, for example, has refocused energy on ending the war on Gaza. After Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg began participating in anti-genocide protests, an Israeli army spokesperson accused her and anyone who identifies with her of being a terror supporter.

At Columbia University, students involved in the movement for divestment from fossil fuels are now also pushing the university to divest from companies working with Israel. Administrators responded to the students’ Palestine solidarity encampment, which escalated into the occupation of a school building, with mass arrests and an invitation for the NYPD to lurk on campus until after graduation.

Alumni of Columbia’s Climate School responded with a letter urging the school to divest, stating, “Columbia’s crackdown mirrors and contributes to the irredeemable rising repression and surveillance against climate activists worldwide.” They added, “As Columbia moves in lockstep with authoritarian assaults on democracy by unilaterally crushing dissent, it pours fuel on the flames of a burning planet.”

At New York’s Cornell University, the student group Climate Justice Cornell was suspended last week for its involvement with a Palestine solidarity encampment on campus. The climate group was accused of registering the event with campus administrators under “false pretenses.”

“They're afraid of what we have to say and the people that we can touch,” said Cornell senior Yanenowi Logan, who is Deer Clan from the Seneca Nation and has been negotiating with campus administrators. When she and I spoke, administrators had already suspended several students, telling negotiators that more suspensions were imminent. Since Logan is in her final weeks of college, she is now supporting the movement from outside of the camp. “These are very arbitrary policies being pulled out of the woodworks to restrict our very peaceful act of civil disobedience.”

Asked for comment, a Cornell spokesperson pointed Drilled to an online statement by Cornell president Martha Pollack, which said the encampment violated the school’s “content-neutral” rules and was causing disruption. “The noise from the associated rallies can be heard in classrooms on the Arts Quad and the encampment has displaced other previously registered events on the Arts Quad,” Pollack wrote. “As this encampment continues over multiple days, it is diverting substantial public safety and student life staff and resources from other important matters.”

The Cornell encampment was established by a new group called the Coalition of Mutual Liberation, and their demands go beyond a ceasefire in Gaza and divestment from Israel. Cornell is a land grant university, founded using seed money obtained via the 1862 Morrill Act, which took land that had recently been stolen or coerced from Indigenous people and distributed it to the nation’s new institutions of higher education. No university benefited more from the act than Cornell, whose founder obtained rights to 977,909 acres taken from tribes in 15 states.

The students are demanding that mineral rights on those lands be returned and restitution paid to the tribes dispossessed via the Morrill Act, including the Gayogo̱hó:nǫɁ people, on whose land the Ithaca campus was built. They also want a Palestinian studies department and the removal of all police from campus.

“When we talk about genocide, we also gotta think about the ground beneath our feet,” said Logan. “What's happening there, it happened here too.”

Cross-movement organizing between land defenders, environmental activists, and Palestinian activists did not just begin after October 7.

At Standing Rock, multiple Palestinian liberation groups expressed support for the effort to stop Dakota Access Pipeline construction, and a number of Palestinians spent time at the encampments. The pipeline security company responded with surveillance. “The PYM [Palestinian Youth Movement] is currently in Standing Rock and currently we are monitoring any internet chatter that they produce,” wrote one TigerSwan intel analyst in an email that September. He noted that a second organization, Samidoun, or the Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network, had issued a statement in support of the tribe. “Sir it is my assessment that the Samidoun is the more radical group of the two and I am working with Max to find out who are the key players.”

“Please insure these organizations and any further developed individuals make it to our database,” replied TigerSwan’s deputy program manager. Neither TigerSwan nor its client, Energy Transfer, responded to requests for comment.

After Standing Rock, anti-protest laws swept the U.S., backed primarily by right-wing politicians and fossil fuel industry and law enforcement lobbyists. Repressive laws proliferated again in the wake of anti-police brutality protests in 2020, after George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis. Such laws are now spreading internationally in response to large-scale climate protests around the world. Civil liberties advocates call it lawfare or judicial harassment.

As reporter Dharna Noor pointed out in The Guardian this month, lawfare against environmental activists in recent years has at times drawn on efforts to crush pro-Palestine organizing. For example in 2017, Texas passed a law to ban the state from doing business with groups committed to boycott, divest, and sanction Israel. Inspired by the law, lawmakers moved in 2021 to ban the state government from conducting business with organizations that divest from fossil fuel companies.

Now, just as happened after the George Floyd and Standing Rock protests, bills are being considered in six state legislatures to enhance penalties for blocking roads, with most of them explicitly framed as a response to pro-Palestine protests. New York’s proposed new law would label protesters blocking roads as domestic terrorists, and Tennessee's bill only awaits the governor’s signature.

This time, as reporter Adam Federman noted in a story for Type and In These Times, federal lawmakers have also entered the game. The Senate is considering a bill to establish criminal penalties for blocking a road. A second bill, introduced by Republican Senator Tom Cotton and titled Stop Pro-Terrorist Riots Now Act, would increase rioting penalties.

Meanwhile, Louisiana’s House of Representatives passed a bill that would expand the state’s racketeering law so it can be used against people who participate in a “riot,” write graffiti on a “historic” building, or damage “critical infrastructure.” Georgia sought to expand its own Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization, or RICO, law, but the measure stalled. Such laws, which were meant to go after the mafia, have repeatedly been used to accuse supporters of environmental defender movements of operating as part of an illegal conspiracy.

The anti-terrorism to anti-protest pipeline

There’s another way anti-protest laws have repeatedly advanced: A deadly attack is conducted by a radical Islamic group that is deemed terroristic. Suddenly, new anti-terrorism laws spread across the nation and the world. Environmental movements learned after 9/11 how easily laws and police funding designed to protect against terrorism can be repurposed to suppress environmental and land defense movements, with industry support.

That’s not just true in the U.S. In the Philippines, for example, an anti-terrorism law passed in 2020 is being used to label Indigenous land defenders as terrorists and shut down their bank accounts. In India, the 2022 Unlawful Activities Prevention Act has been used to surveil and arrest environmental activists, while the Prevention of Money Laundering Act and Foreign Contribution Restriction Act have been used to strip multiple environmental and social justice groups of their nonprofit status and seize their assets, alleging that they are receiving foreign money to undermine the government or “fund terrorism.”

In the U.S., since 9/11, movements dedicated to halting polluting infrastructure like oil or gas pipelines have often been targeted under the guise of protecting “critical infrastructure.” If an attack on critical infrastructure can be considered terrorism, then Indigenous land defenders can be framed as ecoterrorists. Since Standing Rock, that framework has been used to advance corporate-backed critical infrastructure protection laws that enhance penalties for people protesting near fossil fuel projects. Two such laws passed as recently as this spring in West Virginia and Florida.

Equating Palestinians with terrorism is an even older idea. A recent report by Palestine Legal and the Center for Constitutional Rights underlined that some of the U.S.’s earliest laws on terrorism were advanced by pro-Israel groups and aimed at Palestinians. In the post-October 7 context, the premise is that the war on Gaza is Israel’s attempt to obliterate Hamas, which has been designated a terrorist group. If people are supporting a Palestinian uprising, or, simply, an end to Israel’s mass-killing and starvation of civilians, according to proponents of this thinking, they can be framed as supporting Hamas, a terrorist group. Enhancing this brand of criminalization is the allegation that Palestine solidarity organizers are antisemitic. Here, the idea is that the Israeli state and Zionism are inherent to Jewish identity; to be anti-Zionist or demand the Israelis return land to Palestinians or call for a Palestinian uprising is to be antisemitic. It’s an argument that Jewish antiwar organizers, in particular, wholeheartedly reject.

Immediately following Hamas’s October 7 attack, the Anti-Defamation League — which has increasingly equated anti-Zionism with antisemitism — sent a letter pushing for universities to investigate the group Students for Justice in Palestine under laws preventing material support for terrorism. Around that time, Florida banned SJP on campuses for allegedly supporting terrorism, though later backed off after a lawsuit from the American Civil Liberties Union. Meanwhile, law enforcement agencies including the FBI are refocusing resources on uncovering funding sources for Hamas — which will inevitably mean the targeting of nonviolent antiwar protests as well as Muslim communities. President Joe Biden announced that the federal Justice and Homeland Security departments are partnering with university police to monitor antisemitism — which, again, will mean monitoring pro-Palestinian speech.

Mara Verheyden-Hilliard, an attorney and executive director of the Partnership for Civil Justice Fund, said that one of the most worrisome legal developments she’s seen since October 7 is House Republican and Democrats’ passage of a new terrorism financing bill. If it is signed into law, it would allow the U.S. Treasury Secretary to terminate the tax-exempt status of “terrorist supporting organizations.” Verheyden-Hilliard said, “It gives virtually unfettered discretion with no due process to a political appointee of any administration to strip nonprofit status from any organization with which they disagree.” In their press release, sponsors Brad Schneider (D-IL) and David Kustoff (R-TN) said it was an effort to cut off organizations supporting Hamas. Analysts have said it’s the starting point for “a new category of legal harassment.”

Separately, an Iowa bill would remove the recognition of campus groups and cut financial aid for students who “support or endorse terrorism.”

At the same time, at least half a dozen states have introduced bills to redefine antisemitism as including anti-Zionism. At the national level, a bill that would do the same passed in the House of Representatives with the support of 13 Democratic co-sponsors.

As organizations work intersectionally, equating support for Palestinians with antisemitism and terrorism does not just impact Arab, Muslim, and Palestinian groups — it provides a pathway to spy on and disrupt a whole range of protest movements, including environmental and Indigenous movements.

El-Zabri, the Palestinian activist surveilled at Standing Rock, was among 79 people arrested this week while protesting at the University of Texas at Austin. “It really felt like the same as Standing Rock, when we were facing the police,” he said. “There was a whole army that looked like it was at war in riot gear. They eventually used tear gas and pepper spray.”

He added that Indigenous organizers have consistently worked in collaboration with Palestinian activists in Austin. “When I was in jail, every night there were Indigenous people drumming and dancing for the inmates,” he said.

Logan, of Cornell looks back even further than post 9/11 policies to understand the current moment and what’s happening in Gaza and on campuses. She pointed to New York’s early history, when General George Washington and his troops destroyed the villages and food systems of the Six Nations, which includes Logan’s people.

“In the Clinton-Sullivan campaign, George Washington ordered troops to burn down our native orchards and our cornfields. Throughout history, we've had our bison, our sheep killed, and this is something that was an effort to kill Indigenous people and take away their way of life and make sure that they never had a home or land to come back to,” she said.

A similar pattern is now playing out on Palestinian land — but, in this case, a wide network of people is speaking out against Israel’s actions. Logan said that by standing up for Gazans, she and other Native organizers are also standing up for themselves. “We want to be able to show them that, hey, we're still here,” she said. “You can try to kill us. You can burn our crops. You can do whatever you want to do, but we're still going to persist.”