Cover photo: An LNG tanker in Ishikari Bay, Japan. Credit: とまりん♪, CC BY-SA 2.1 JP, via Wikimedia Commons

On June 30, 2025 at 9:34am, an email slipped into the inboxes of two Australian government bureaucrats. It was Monday morning and the message carried the casual tone of a familiar friend. The author, an employee of Japanese energy giant INPEX, said they hoped the recipients had had a lovely weekend. Copied into the email was a colleague from Japan’s largest power provider, JERA. Attached, they said, was a fact sheet they had thoughtfully prepared ahead of time for the officials with the Departments of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, and Industry, Sciences and Resources that sought to correct “misinformation” about Japan’s practice of re-selling Australia gas while it was still on the water.

“JERA and INPEX have worked together to undertake detailed analysis of the facts around our LNG supply to Japan to address concerns and correct misinformation about LNG onselling. I mentioned this at the recent gas market reforms meeting we had with your teams,” it read. “We have prepared a facts sheet (attached) with key data and would be pleased to offer your respective departments a briefing (this could be undertaken via Teams) this week.”

“Could you advise if this is of interest and we could set a time that works?”

The intervention took place at a time of increased scrutiny about the relationship between Japanese energy companies and Australia’s gas sector. Australia is one of the world’s biggest gas exporters, vying with the U.S. and Qatar for the top position, and exporting a little over four-fifths, about 83%, of the gas it produces overseas. Historically, Japan has acted as the world’s foundational buyer in the global gas market, soaking up two-fifths of the world’s production and acting as a stabilizing force. This dynamic has created an intimate relationship between the two economies. In Australia’s case, Japan represents its second biggest trading partner after China. As of 2023, Australian gas accounted for two-fifths, 41%, of imported Japanese gas—nearly three times as much as Malaysia and five times as much as Russia—in a trade worth AUD$35bn in 2023. Japan, meanwhile, has plunged tens of millions of dollars into fossil fuel extraction and enabling infrastructure both in Australia and across South East Asia through its export finance agencies, such as the Japanese Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), that have continued to act as lenders where private institutions have pulled back. Along with Korea, Japan is thought to have sunk AUD$20bn into these projects to get some of Australia’s dirty gas projects, like the Barossa gas field operated by Santos, off the ground.

The practice of reselling Australian gas cargoes has become emblematic of the broader effort by corporate Japan to lock in fossil fuel extraction and consumption in Australia and across the wider Asian region. Where “re-export” refers to cargoes that enter Japan and are then re-exported back out, “reselling” refers to trades that take place before they ever arrive at the destination, while the tankers are still on the water. The scale of this trade was first exposed in 2024 when a report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) revealed what was then an open secret among industry: as demand fell by a whopping 25%, Japan was buying way more gas than it needed and re-selling the excess. Instead of buying less gas, Japanese trading houses kept buying larger volumes to resell while they were still on the water to buyers across Asia. The motivation was part profit, part strategic geopolitical interest. With one eye on an assertive China, Japan saw advantage in positioning itself as a middleman in the gas trade supplying an essential fuel among its neighbors. It also meant Japanese traders could make out like bandits after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

It was a state of affairs that did not go unnoticed in Australia, the origin point for this trade, particularly as domestic gas prices began to rise. The cause of those gas price hikes was eventually attributed to massive gas exports, triggering calls for the government to intervene and reserve a portion for domestic use only, and bringing more scrutiny on the activity of Japanese companies. Around the start of 2025, report after report examined the issue. In response, Japanese companies began to push back. A flashpoint came in March 2025, when Hitoshi Nishizawa, a senior vice executive from Japanese power giant Jera, told the Future Energy Forum in Perth that environmental regulations and rising costs could cost Australia “thousands of jobs, billions of dollars in lost revenue and weaken regional trade partnerships”. This was a sentiment that was later adopted and repeated by Australian political leaders. In one example, West Australian Premier Roger Cook gravely warned of “major trade concerns in Japan” in July last year over plans by the federal government to create an east coast gas reservation policy.

Japanese business and government figures have brought considerable pressure to bear on domestic Australian politics even before the 2025 gas disputes. The first significant intervention took place in March 2023 when Japanese ambassador, Yamagami Shingo, addressed an audience at the Inpex Luncheon that included Federal Resources Minister Madeleine King and Trade Minister Don Farrell, their shadow ministry counterparts, Tania Constable, the head of the Minerals Council of Australia, Samantha McCulloch, the head of Australia’s oldest oil and gas industry association, Australian Energy Producers.

“Japan and Australia have grown—and continue to grow—together. You only have to look at the vibrant streets of Japan’s never-sleeping capital,” Shingo said. “It’s hard to imagine the neon lights of Tokyo ever going out, but with Australia now supplying 70% of coal, 60% of iron ore, and 40% of Japan’s gas imports, this is exactly what would happen if Australia stopped producing energy resources.”

It is against this backdrop that the June 2025 meeting request—revealed through a Freedom of Information by the UK-based think tank InfluenceMap—took place. That meeting is one among 24 encounters identified by InfluenceMap in which it says Japanese companies involved in major Australian gas projects met privately with Australian government officials since the election of the centre-left Labor government in May 2022, though not all lobbying was conducted directly. Influence Map’s Jack Herring, an author on its report, said the group was able to identify five companies with equity stakes in 13 major Australian gas projects who were also members of key industry associations. These associations acted on behalf of their member companies, a tactic that allowed individual companies to remain out of the spotlight even as they helped “shape policy indirectly.”

“The scale of it is eye-opening and is larger than what the Australian public is aware of,” Herring said. “Documents like these indicate these companies are lobbying behind the scenes very privately and this privileged access enjoyed by Japanese companies underscores the need for wider transparency reform in Australia.”

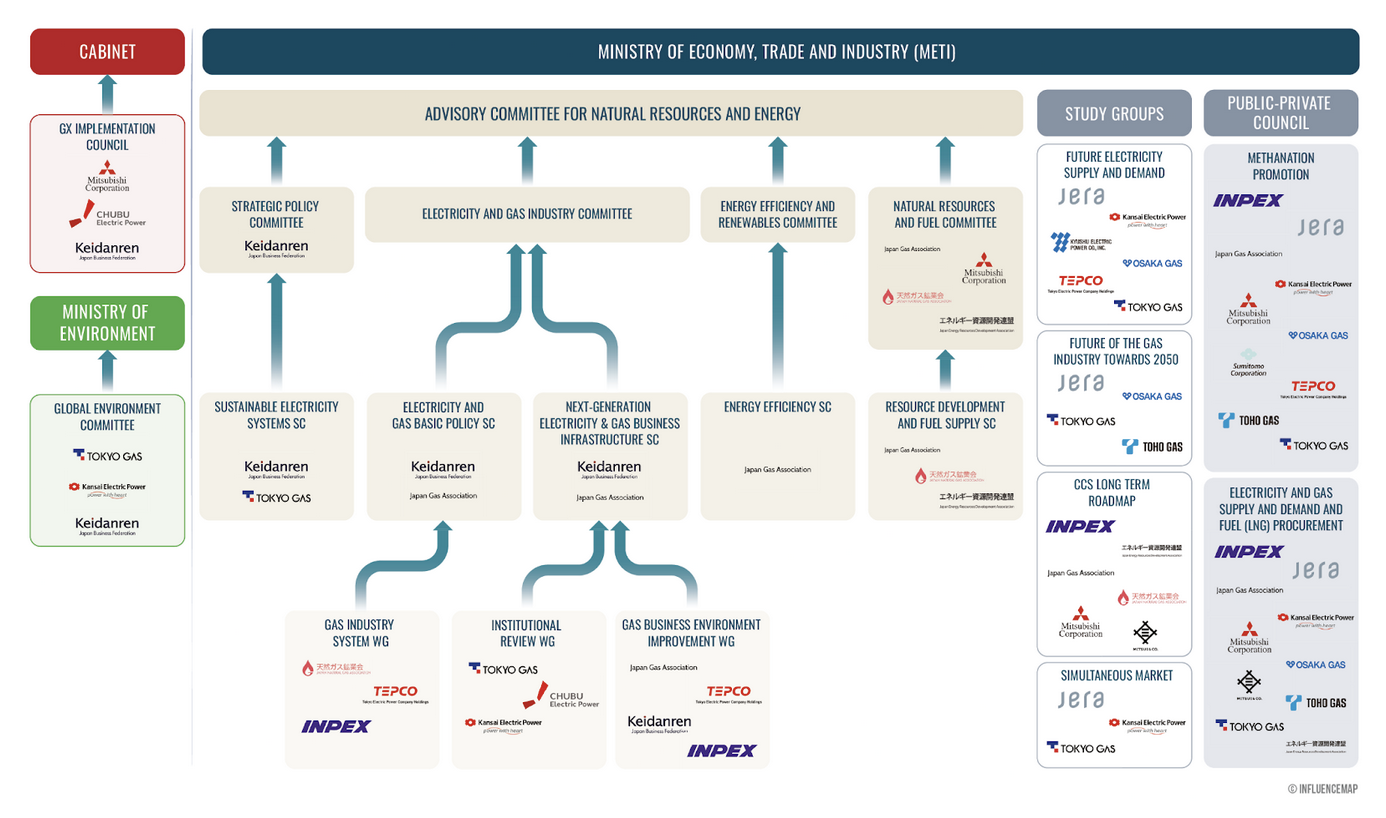

Corporate Japan’s bravado when intervening in Australian domestic politics might be attributed to the role industry plays in domestic Japanese policy making. Influence Map reviewed key governmental bodies and committees that fed into the policy-making process in Japan for issues like climate change and energy, and found Japanese fossil fuel companies and their industry associations held 69 positions. The outcomes, it noted, are often favorable to business. In one example, it pointed to Japan’s 7th Strategic Energy Plan which projected fossil fuels would continue supplying up to two-fifths of Japanese power production by 2040, and institutionalized a “buffer” system that required companies to maintain enough spare gas to supply the domestic market—a mandate that has since become a justification for the practice of reselling gas elsewhere across the region.

“It gets very difficult to tease out where the line between government and industry ends in Japan,” Herring said. “We can see the influence that industry have been able to exert over final policy decisions.”

A simplified version of the committee structure and committee membership for illustrative purposes sourced from

Though it was difficult to know whether a single lobbying interaction resulted in a specific outcome, Herring said it was possible to gauge results when government officials and political leaders adopt industry-preferred language and framing. One example, he said, was a 200-page brief prepared for federal resources Minister Madeleine King ahead of a visit to Japan in October 2024, released under Freedom of Information, where talking points supplied to the minister were similar to those used by industry. These included suggestions that the country is “committed to encouraging targeted investment into new gas projects in Australia”. These are ideas she has continued to echo. In October 2025 she told the Australia-Japan Business Cooperation Committee conference: “We will not be doing anything that harms investment or alters existing contracts, or which jeopardizes Japan’s energy security.”

Of course, Japanese companies are not alone in seeking to pressure the Australian government on energy and climate issues. In early February the Australian Electoral Commission published donations data from the 2024-to-2025 period offering a glimpse into the fossil fuel money sloshing around the Australian political system. The largest fossil fuel donations during the period, which included the May 2025 federal and October 2024 Queensland state elections, originated with industry associations. The Minerals Council of Australia, which represents the broader Australian resources sector including coal producers made donations totalling more than $1m, with $107,885 of this going to Labor, $760,085 flowing to the Liberals and Nationals, and the rest flowing to minor parties. Australian Energy Producers, Australia’s oldest enduring oil and gas industry association, contributed $87,450 to Labor and $123,239 to the Liberals and Nationals. Other, lesser known, industry lobby groups to make significant contributions were Coal Australia, which gave $12,500 to Labor and $227,150 to the Coalition, with The Nationals receiving the majority – some $132,650. LET Australia, which lobbies on behalf of CCS firms, gave $75,900 to Labor and $117,084 to the Liberals and Nationals.

Indian coal producer Adani, rebranded in Australia to Bravus, was the source of the single largest fossil fuel donation, giving $121,000 to Labor and a massive $621,500 to the Liberal National Party of Queensland, with smaller donations to minor parties. The company appears to have structured its donation to exploit a loophole between state and federal laws to avoid real-time disclosure requirements in Queensland following the state election there. Billionaire Gina Rinehart’s Hancock Prospecting, which operates coal and iron ore mines, donated $204,000 to the Liberal Party. From the petroleum sector, Santos, Woodside, Tamboran Resources, Senex, Chevron, Ampol and INPEX gave a combined $851,845.

Claire Snyder, CEO of Climate Integrity, a not-for-profit working on climate accountability, said fossil fuel producers were among the biggest donors to all sides of Australian politics. In its own analysis, her organization identified close to $4m in donations, with INPEX the third largest individual donor among a cluster of petroleum producers.

“There has been a huge amount of influence sought by the fossil fuel industry broadly,” Snyder said. “We can’t prove that political donations are influencing specific decisions, but it raises the question of what are these companies seeking? What are they getting in return?”

“And this data is coming out in a particular context for the community and for voters. It’s coming out after an intense summer for extreme weather, where communities are suffering climate impacts so it is frankly pretty outrageous and hurtful to see that the industry driving that extreme weather and hardship, appears to be able to buy a seat at the table.”

Others raised questions about the veracity of information companies shared with government officials and political leaders. When shown INPEXs June 2025 fact sheet sent to government officials, IEEFA analyst Kevin Morrison said it was selective and cherry-picked data. Across six broad dot points, the company suggested that Japan’s “buffer” system forced them to buy significant quantities of Australian gas, directly rejected “suggestions of profiteering in relation to the on-selling of Australian LNG” saying that traders often took a loss, and claimed it was “misleading” to suggest Australian exports had any effect on domestic gas prices.

“According to 2024 statistics published by the Gladstone Ports Corporation, only six per cent (1.46Mt) of exported LNG volume from Gladstone (24.0Mt) went to Japan,” it said.

Though it was true INPEX only exported a small quantity through the Gladstone LNG plant in northern Queensland, Morrison said the company drew most of its gas from elsewhere in the country, and preferred to export from gas processing plants in Darwin in the Northern Territory. Operating out of this city, in a territory with a population around 250,000 people, and gas networks independent from those on the east coast, was a tactical choice he said, as it made it unlikely the company would ever be made to reserve a portion of its export production for domestic use. To highlight Gladstone, he added, was a misdirection as that plant is directly connected with markets that service Australia’s eastern states.

“In that case, why would they care [if a gas reservation policy was introduced or exports were being criticized]?” He said. “If they’re not a big buyer of east coast gas, then they shouldn't be bothered. Why are they getting involved in a political debate where they admit they have no economic interest?”

Similarly, Morrison said though the practice of reselling cargo on the water was opaque and hard to track, claims Japanese traders were taking a loss when re-reselling Australian gas should be treated with deep skepticism.

“These Japanese companies are not doing any of this for anyone’s benefit,” he said. “They aren’t benevolent organizations. They’re organizations listed on the stock exchange. They’ve got shareholders. They’ve got stakeholders. They wouldn’t be providing a service to procure gas unless there was something in it for them.”

“They say it’s about energy security, but this is really about making money for their utilities.”