Photo credit Jan Arrhénborg / AGA, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

On 7 February, US President Donald Trump walked out of a meeting with Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba in Washington and announced what he presented as another quick trade win for his administration. Japan, Trump said, was about to start buying US gas “immediately”.

“We’re very happy that they’re going to start immediately,” he said.

No specific deals were announced, but in the moment it looked like the first clear step toward locking in Trump’s “Drill, Baby, Drill” approach to energy across south-east Asia, with its goal to establish US “energy dominance”, total disregard for the effects of human-caused climate change and willingness to rubber stamp new gas projects whatever the costs. By supplying American gas to major trading partners such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, the Trump administration’s basic plan is to bind these countries closer to it by making them dependent on US fossil fuel production. According to analysts, however, the reality of the economic, political and even geographic landscape makes the Trump administration’s pitch more like an attempt to defy financial gravity.

For Ishiba, the moment has offered temporary relief. Days before, Trump imposed tariffs on Canada, Mexico and China, and threatened Colombia – a country that supplies just over two two thirds (64%) of US coal imports, with retaliatory tariffs over a diplomatic dispute concerning forcibly exported immigrants. The willingness of a US President to aggressively threaten its allies and the global economy was very bad news for Japan, a country particularly vulnerable to US tariffs.

Back in the 80s, Japanese car makers had crushed the American auto industry by pioneering ‘just in time’ manufacturing but four decades on in 2023 Japan was selling 1.49m cars to the US. Promising to buy US gas in the moment offered a cheap way to blunt Trump’s willingness to start a trade war by telling him what he wanted to hear – a strategy quickly picked up by six other south-east Asian countries in the following days. Before long European countries, too, pledged to buy US gas to keep Trump onside – Europe’s “Affordable Energy Action Plan” went so far as to reference “the Japanese model” as a basis for this fossil-fuel-based diplomacy. Since then, Trump has announced reciprocal tariffs up to 25% on multiple industries, including Japanese-made cars and other products.

This crude attempt to redraw the global economic map has since put a spotlight on a corner of the world that has long been the focus of US and Chinese geopolitical manoeuvring, and whose fossil-fuel dependence has often been used to justify expanding the production of oil and gas in countries such as the US, Canada and Australia. From claims about “bridging fuels” to “firming”, industry advocates in these countries have insisted gas displaces coal in southeast Asian countries to justify ongoing government support – a claim proved false by US Department of Energy modelling that found for every unit of coal displaced in South-east Asian economies, two units of renewables were displaced.

As technical and convoluted as this can sometimes be, the flow of trade through southeast Asia is hugely significant both for climate change and for the world economy. Japan itself has a long, storied history in the global gas business as a foundational player in the global gas market and the second-largest consumer worldwide. Until the rise of China, the small island country, home to 124m people and a thirsty manufacturing base, has acted like a giant sponge, absorbing gas shipments off the ocean in a way that has kept the global trade ticking over for decades. Japanese gas consumption has been so consistent, its demand is factored in when oil and gas companies weigh whether to pursue a new development.

The Fukushima disaster in 2011 only intensified Japan’s reliance on gas and since that time, the country has prized stable and long-term relationships with its suppliers, two of which, Australia and Qatar, have vied to be the world’s top gas supplier in recent years. Qatar, however, has fallen away, leaving Australia to largely dominate. The country made up 38% of Japanese gas supply in 2024, according to Japanese government financial accounts. Meanwhile, Russia and the US each supplied 9% and 10% respectively.

To keep the gas flowing, Japanese export finance agencies (EFA) – government-backed investment vehicles – have even acted as early investors on major new projects or the supporting infrastructure needed to make them work. When banks and other lending institutions began to shift away from fossil fuels, Japanese taxpayer money has poured into LNG export and import terminals, processing plants and docks. Without the support of Japanese and South Korean EFA’s for instance, the $5bn Barossa gas field in northern Australia – described by critics and analysts as a carbon-dioxide emissions factory, with an LNG by-product – would not have been able to get off the ground.

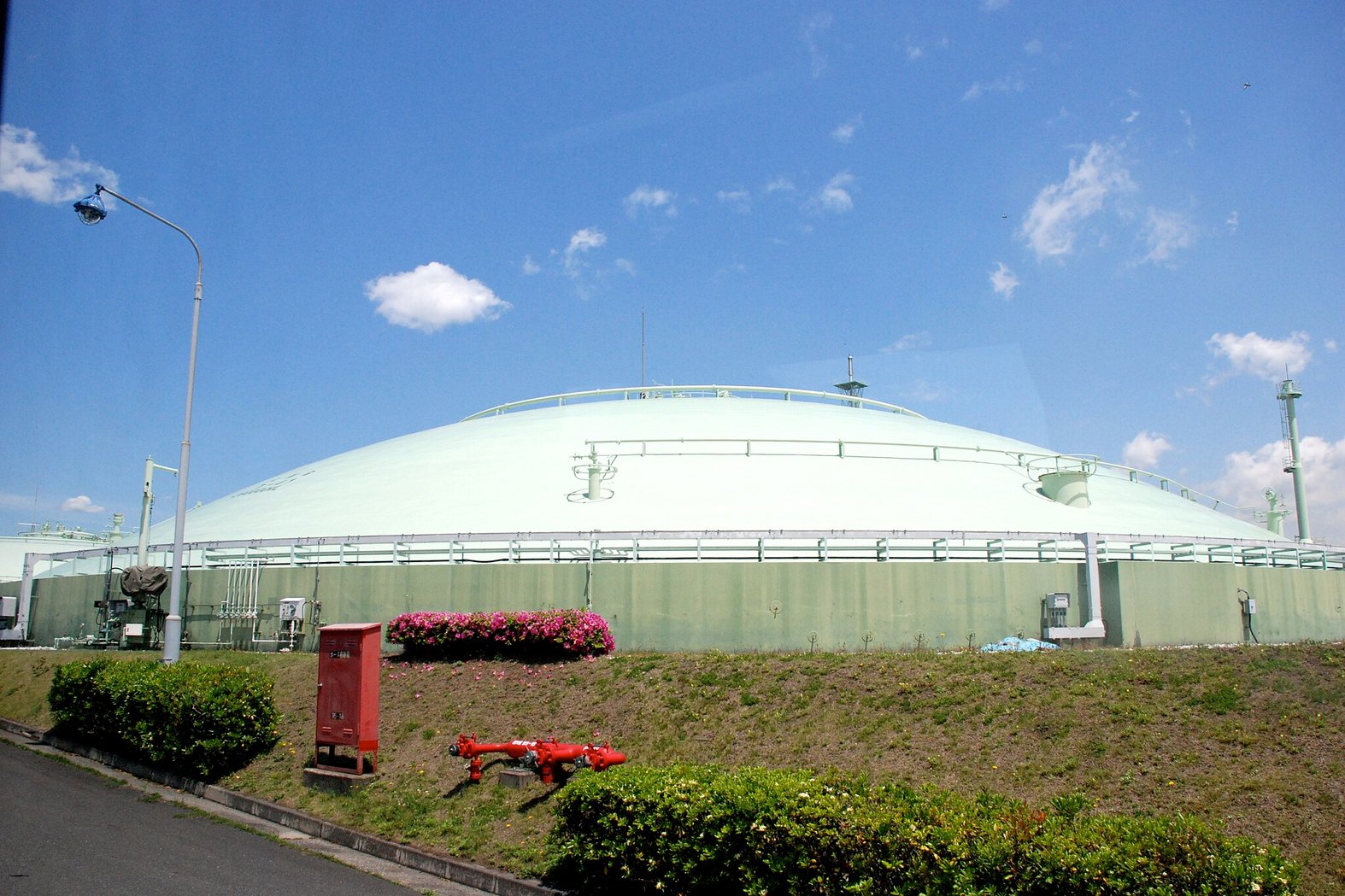

LNG storage facility in Japan. Photo credit: Herman Darnel Ibrahi…,

It was circumstance, however, that broke the Qatari hold on Japan. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, this sort of flexibility became an extremely valuable clause in Japanese contracts. As European countries rushed to end their reliance on Russian gas, and prices began to spike, the long-term, fixed contracts Japan once prized suddenly became a liability.

Qatari gas contracts come with a catch, what’s known as a “destination clause”. These clauses force a gas buyer to consume the cargo, once purchased, at its destination, meaning it cannot be resold.

Australian gas contracts, by contrast, have had no such restrictions.

Meanwhile, as Russian tanks were attempting, and failing, to roll on Kyiv, Japan was consuming less gas than it was buying, partly because it began to switch its nuclear reactors back on. Between 2023 and 2024, Japanese gas demand fell by a massive 25% -- a significant drop for a foundational buyer in the global gas market – and traders quickly sought to cash in. Cargos sailing out of Australia that were initially bound for Japan were redirected on the water to ports across southeast Asia in a process known as “reselling”. Where “re-export” refers to cargoes that enter Japan and are then re-exported back out, reselling refers to trades that take place before they ever arrive at the destination.

The decision earned Japanese gas traders eye-watering sums of money and worked to entrench the country’s regional influence in the short-term. Japan’s status as a major trading partner had already earned it a certain trust, but this reliance only deepened as it began to supply larger and larger amounts of energy to its neighbours.

It is against this backdrop that the US is now seeking to entrench Japan’s reliance on American gas, but Sam Reynolds, lead gas analyst with the Asia team from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis says the structural environment means things may not work out as planned. Reynolds, who co-authored the research that helped expose Japan’s dealing in Australian gas in late 2024, says revealing this open secret exposed the contradiction between the Japanese government’s public statements insisting it needed more Australian, Canadian and US gas and its actions. Any claims by Japan that it needed the gas to keep the lights on didn’t stack up when it had set itself up as a middle-man to on-sell Australian gas.

Between the need to cut carbon emissions to head off the existential threat of climate change, and an emerging gas glut, Reynolds says the financial risk taken on by Japanese traders represents a significant issue going forward. With Qatar on the verge of bringing new gas projects into production over the next few years, he says that the global gas market is about to be flooded with supply that would cause prices to fall in a way that threatens to catch out those trading gas, and those building new projects.

“The large reason all these gas projects are being built is they’re counting on demand by some of the largest historical buyers like Japan,” Reynolds says. “They’re counting on Japan to absorb cargos from off the water, to absorb cargos from the global market, rather than reselling them, which lowers prices.”

“So not only is there a glut materialising but you have these legacy importers contributing to that glut by reselling, which increases the available supply and lowers prices further.”

Reynolds suggested this scenario would be “bad news financially” for Japanese traders caught out as prices drop. This was made more likely given the Trump administration’s plan to flood the global market with US gas – a plan that would ironically come at the expense of US consumers.

Despite Trump’s crude push to establish “energy dominance”, Climate Energy Finance founder Tim Buckley said it was more likely the new administration would only succeed in driving up domestic US gas prices.

“One of the reasons why America has had one of the biggest reindustrialisations is that it had the lowest energy price in the world. They effectively just traded that away for the profit of Exxon and Chevron,” Buckley says. “You’re removing one of the competitive advantages of America, which is one of the lowest price gas markets in the world. It’s what happened to Australia when it moved to export LNG.”

Cheap gas, high labour costs and higher costs for inputs like steel and transport mean any US oil and gas renaissance is unlikely to be competitive – and more likely short-lived. Many proposed new projects involve shale gas, a notoriously “flash in the pan” sector where operations run dry after a few years. Across southeast Asia, Reynolds says, new gas power plants in Asia are far more expensive to run when compared to coal and renewables. Gas producers and traders have been hanging on to the hope that a gas glut will drive the price of the fuel down far enough to change the calculus for southeast Asia, but it’s a risky move and one that marries short-term brinksmanship with expensive long-term infrastructure plans and contracts.

The balance of these dynamics does not bode well for one of the Trump administration’s signature projects: Alaska LNG. The $44bn, decades-old proposal has become a centrepiece of the new approach thanks to the advocacy of Doug Burgum. As secretary of the US Department of Interior, Burgum, a former governor from North Dakota whose family owns property that directly benefits from fossil fuel extraction, has pitched Alaska LNG as a much-needed replacement for Sakhalin-2 and the Russian gas that currently makes up a portion of Japan’s energy mix. The project, which would require building a 800m (1287km) perma-frost resistant pipeline through some of the most rugged, remote environments in North America, has so far failed to attract buyers for the gas it would produce. Even if commissioned today, the project would still be another decade before it enters production.

A Reuters report, citing unnamed government sources, found southeast Asian governments were considering their options as Trump administration officials asked Japan to take out long-term purchase agreements and make infrastructure investments in Alaska LNG. Using maps, these officials sought to impress upon the Japanese delegation that any US gas they buy would avoid global trade chokepoints in the Straits of Hormuz and Malacca and the South China Sea. According to the same report, Alaska LNG’s project developers have been lobbying Inpex, an oil and gas company partly-owned by the Japanese government, to invest in the project – a key step toward attracting the additional buyers needed to make it viable.

Inpex, however, has more than a few of its own problems, including the high carbon-dioxide levels in Australian gas underpinning its demand for the Australian government to subsidise the creation of a carbon, capture and storage industry. For Japan and other southeast Asian countries, Reynolds says, the long-lead time on building Alaska-LNG and the complicated engineering challenges presented by its lengthy pipeline means any gas Japan agrees to buy will do nothing to help it in the short term. Even without the geopolitical risks created by Trump’s loose talk about taking back the Panama Canal and shaking down US allies, shipping gas from the east coast of the US, Canada or Mexico is an expensive proposition for southeast Asia, when Russia and Australia are on its doorstep. Where it might take eight days to ship cargo from Russia’s far eastern flank, it may take 30 days to bring the equivalent from the US – a time-premium that is going to factor into any decision making.

“None of these US Japanese announcements have been accompanied by any tangible, commercial deals,” Reynolds said. “Nothing has changed, except needing to placate the Trump administration, and I think that’s what’s happening.”