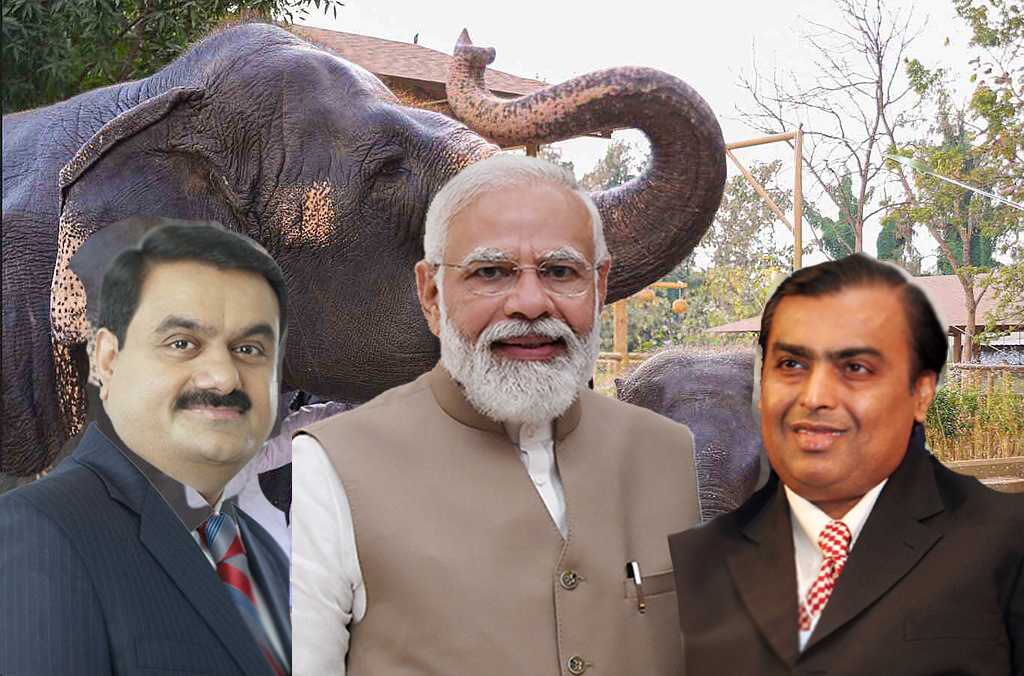

Two stories that unfolded in India over the past month show how the Modi government shields billionaire coal and oil tycoons from public scrutiny. In one case, the Supreme Court of India, based on a report submitted to it quickly and under seal, exonerated a private zoo of large-scale trafficking of wild animals from around the world. The zoo is owned by the Ambani family, which runs Reliance Industries, a corporation with major operations in oil and petrochemicals.

The other case concerns the coal giant Adani Group, which convinced a local court in New Delhi to restrain what it deemed to be “defamatory” journalistic reporting. Following that ruling, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting under the Modi government, passed an order requiring multiple journalists and YouTubers to take down their reports and videos referencing the company, even in cases when they only made a passing, uncritical reference to Adani. Various journalists and media houses legally challenged the orders by the local court and the broadcasting ministry and some of them were eventually granted relief. However, the sweeping directives passed in favor of Adani raise grave questions about the ability of India’s institutions to hold powerful businesses accountable.

Taken together, the Ambani and Adani Group cases highlight weaknesses of the country’s judiciary and executive branch of the government, as well as India’s mainstream media. The two businessmen own television media channels like Network18 and NDTV that dutifully failed to scrutinise both the wrongdoings of the companies that own them and the failures of courts and the Modi government.

‘Star of the Forest’ off the hook

On 15th September, the Supreme Court of India acquitted ‘Vantara’ of multiple allegations ranging from illegal acquisition of wild animals and their mistreatment in captivity to financial impropriety and money laundering.

Vantara, which means ‘star of the forest’ in Hindi, is a private animal rescue centre and zoo founded by Anant Ambani, the youngest son of oil tycoon Mukesh Ambani who is the richest man in Asia. The Ambani family has close ties with Indian prime minister Narendra Modi. In fact, the prime minister inaugurated Vantara as a “unique wildlife conservation, rescue and rehabilitation initiative” earlier this year.

Mukesh Ambani is a billionaire businessman and the chairman and managing director of Reliance Industries. Vantara is owned by the Reliance Foundation, a philanthropic venture of Reliance Industries, and is located within the Jamnagar oil refinery complex in the western Indian state of Gujarat. The refinery is the world’s largest, with a processing capacity of 1.24 million barrels of crude oil per day.ge

In the last few years, multiple journalistic reports—both by Indian journalists in various media outlets and foreign media—have raised several serious questions about the manner in which Vantara has acquired animals, namely whether they were trafficked from the wild and whether their transport to Vantara complies with regulations and norms established by India’s Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Countries like Brazil and South Africa have also raised concerns about their animals being taken to Vantara. Based on these allegations, two petitions were filed before the Supreme Court.

As of today, Vantara—spanning just about 3,500 acres—potentially houses somewhere around 75,000-100,000 animals including elephants, leopards, caracals, lions, crocodiles, rhinos, and other endangered species that are also exotic to India like Spix’s macaws and Tapanuli orangutans. Neither the exact number of animals that Vantara houses at present nor the species list are publicly available information. And Vantara is not open to public visits.

The court decision to exonerate Vantara was based on a report by a Special Investigations Team (SIT) that the Supreme Court constituted on the 25th of August. None of the four members of the SIT were wildlife experts.

The SIT submitted its report to the Court under seal on the 12th of September. Questions remain about how an investigation that was supposed to deal with a wide-ranging set of issues from global wildlife trafficking to animal welfare to money laundering was completed in just about three weeks. And on the 15th of September, a mere three days after the SIT report was submitted, the Court absolved Vantara of all allegations and ordered for the SIT report to remain sealed even while Vantara was given a copy. So, neither the petitioners nor the general public know what the SIT report contains.

The Court also went two steps further and directed that no complaints based on such allegations will be entertained in the future and stated that Vantara is free to seek deletions of “offending" media publications and pursue legal action for “defamation”.

Adani’s SLAPP suits

Meanwhile, on 6th September, a district court in New Delhi overseeing a defamation suit filed by Adani Enterprises passed an injunction order seeking the removal of “defamatory” reports about the Adani group. The order was passed ex-parte, in other words without hearing the journalists and media organisations that were named in the plea. And it was a “John Doe” order that restrained even those persons who were not named in the plea. The Adani Group was allowed to continuously compile lists of “defamatory material” and seek their removal within 36 hours.

Prominent investigative journalists in India, including Paranjoy Guha Thakurta and Ravi Nair, are named in the plea, as are media organisations like AdaniWatch and AdaniFiles. In a post on X, Thakurta noted that this is the seventh defamation case against him by lawyers representing the Adani Group. These are all Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPP) suits intended to censor and intimidate people who are critical voices like activists and investigative journalists.

Gautam Bhatia, a constitutional lawyer, noted that the action of Indian courts in such instances is often not in line with Indian law. “The established law, which has also been reiterated by the Supreme Court of India, is that if party A goes to court saying X or Y is defamatory, first of all you don’t issue ex-parte takedown orders. And in civil defamation suits, if the defendants say they will justify their actions and bring forward evidence during the trial, then the court is not supposed to order a takedown. The idea is that if the defendant loses, they will pay damages. So, you don’t issue a takedown order at the interim stage and deprive the public sphere of the communication of ideas. But courts don’t follow this at all, especially when the people involved are industrialists, politicians or filmstars who get such orders at their asking. The worst offenders are courts in New Delhi and Bangalore.”

This most recent suit alleged that certain journalists, activists and organisations have damaged the Adani Group’s reputation “with malicious intent”, cost its stakeholders billions of dollars, and also caused massive losses to the image, brand equity, and credibility of India itself. Adani Enterprises Limited has operations across sectors like coal mining, airports, and solar manufacturing.

The allegation also claimed that Adani’s Australian operations “aimed at securing vital resources for India” were repeatedly delayed because of the “defamatory actions” of such reporters, activists and organisations. This is a reference to India’s imports of coal from Australia via the Adani Group. The company specifically noted three domain names: https://pranjoy.in, www.adaniwatch.org and https://adanifiles.com.au for repeatedly publishing “baseless and defamatory content” against the Adani Group and its founder and chairman Gautam Adani. All three websites routinely scrutinise the Adani Group’s mining operations in both India and Australia.

On 16th September, acting on the district court order, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting asked multiple journalists, media organisations and YouTubers to take down reports and videos mentioning Adani. “This is new because in the past, the government didn’t get involved [in such defamation issues],” Bhatia pointed out. The pro-active move by the ministry to shield Adani from scrutiny comes from the Information Technology Act of 2000. Under section 79 of the Act, intermediaries (websites and video sharing platforms that hosted the reports and clips featuring Adani, in this case) are mandated to oblige when the government issues a takedown order.

The next day, the Editors Guild of India issued a statement expressing concerns about “blanket powers granted to a corporate entity coupled with ministerial action in issuing takedown directions.” It urged the judiciary to ensure defamation claims are addressed through due process and also called on the Modi government to “avoid acting as an enforcement arm for private litigants in civil disputes.” Editors Guild of India is a non-profit organisation of journalists and editors meant to protect press freedoms. DigiPub, another nonprofit press freedom organisation composed of digital media, also issued a statement expressing concern and disappointment about the broadcasting ministry’s blanket takedown orders.

On 18th September, another court in New Delhi overturned the ex-parte order stating the journalists and media organisations that were named were not heard and the order is a violation of the constitutional right to freedom of speech and expression. The earlier order, the court noted, “would keep a sword hanging” over every person who makes critical statements. However, this relief order was provided only to four journalists not including Paranjoy Thakurta, although he was eventually granted relief in a September 25th ruling from a court in New Delhi. Meanwhile, the ‘John Doe’ element of the district court order remains, which means that everyone else in India except the ones who got relief from courts (five people as of now) is still at risk of being silenced if they mention the Adani Group.

Newslaundry, a digital media organisation and Ravish Kumar, an independent journalist, then filed pleas before the Delhi High Court challenging the takedown order by the broadcasting ministry. Those cases are ongoing. But regardless of how they are ultimately decided, the manner in which India’s judiciary acted in both the Vantara wildlife case and the SLAPP suits by Adani raises serious questions about its role in enforcing the law and administering justice, and its independence from the executive branch of government. It is important to note that the order by the Supreme Court in the Vantara case also included an open-ended offer to the private zoo to file defamation cases and seek the removal of media reports.

“The government clearly considers industrialists to be people it needs to protect from investigative journalism and it is issuing takedown orders based on the ‘John Doe’ order. And we have to go to court and say the order is illegal,” Bhatia said, noting that the burden of proof is now on the people who seek to hold power to account, not on those who wield their power with impunity.