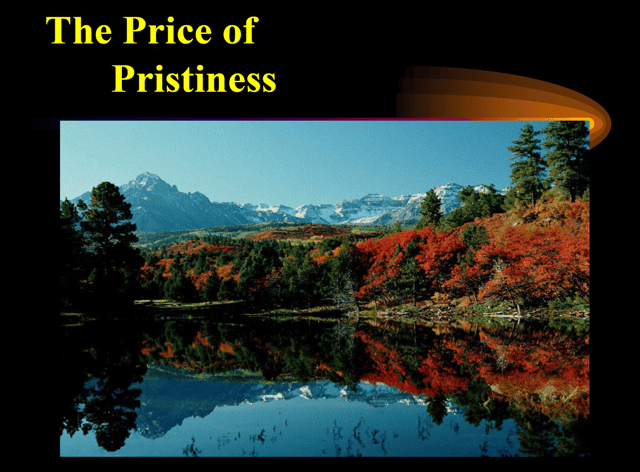

Each generation has brought us a new PR legend who has added new bells and whistles to the disinformation machine. This is a guide to all those we've profiled so far.

Ivy Ledbetter Lee

Ivy Ledbetter Lee is widely considered the father of modern public relations (yes, yes Edward Bernays, Sigmund Freud’s nephew, also sometimes claims that prize, but he started his firm 25 years after Lee).

Lee worked for coal companies and railroads and then in 1914 went to work for the Rockefellers. In response to an ongoing strike at a Colorado mine owned by the family, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. had sent in armed guards, who teamed up with the Colorado national guard to bust up the protest. The men invaded a camp of some 1200 miners and their families, and began setting tents on fire, and then shooting at protestors. Ultimately 22 protestors were killed, including 11 children and two women, who were suffocated by smoke when they got trapped in a pit, trying to hide from the gunfire. The incident came to be known as the Ludlow Massacre. The Rockefellers were just a few years out from the break-up of the Standard Oil Trust, and the Ludlow strike quickly made the son as unpopular as his father. They were in great need of a new image, and Ivy Lee was just the man to give it to them.

An archival news photo of the aftermath of the Ludlow Massacre.

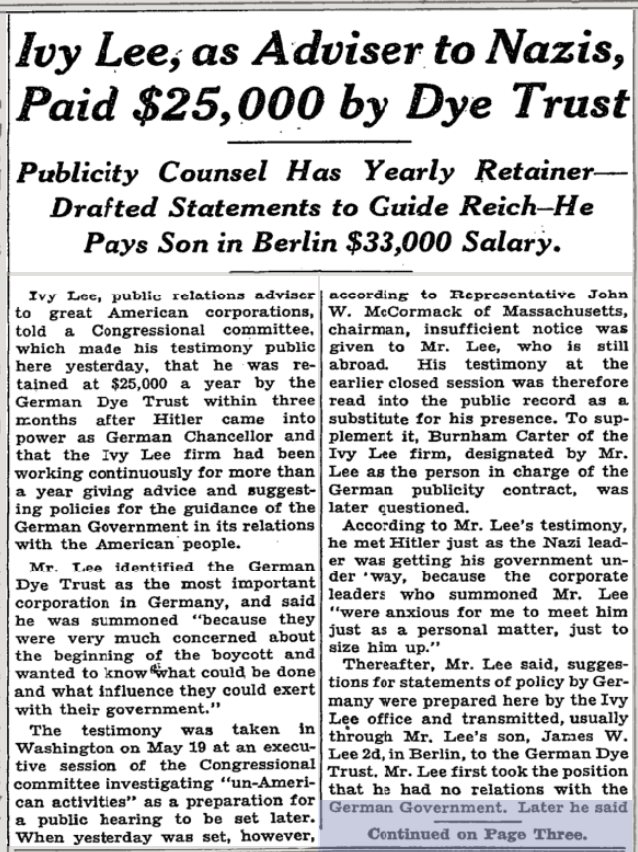

Lee went on to work for Standard Oil and the Rockefellers for the rest of his life. After WWI he helped them bring oil companies together into the first industry PR group, the American Petroleum Institute, back in 1919. In 1929, when Standard Oil signed a partnership deal with German chemical manufacturer I.G. Farben, creating Standard-IG Farben, a joint venture that aimed to develop petrochemicals and synthetic fuels, Lee picked up IG Farben as a client too. And when Adolf Hitler began consolidating power in Germany, Farben asked Lee to come to Germany. The $4,000 a year they were paying him was increased to $25,000 a year, and they offered his son a full-time job in Germany, too, for $33,000 a year, big money at the time. Lee met with minister of propaganda Josef Goebbels, and with Hitler himself, along with various other Third Reich leaders, and advised them on relations with the press and with America in general. When the Nazis were planning to kick out the foreign press, Lee advised them against that idea, and suggested they build relationships with the foreign press instead.

Lee also advised them that Americans would never go for the Third Reich’s stance on Jews, but it’s unlikely that he realized at the time how far that thinking went or what it would lead to in a few short years. Lee was brought before the House Un-American Activities Committee to testify about his involvement on “Nazi propaganda” in 1934. The transcript of that testimony is here.

In addition to creating the "crisis actors" narrative we still see in use today and the press release, and launching a whole new industry in the U.S. that then spread around the globe, Lee pioneered the creation of fake expert organizations. On behalf of the railroads in the early 20th century, he created the Bureau of Railroad Economics. The Bureau had the appearance of independence but was created and funded by Lee, on behalf of his railroad clients. Economists at the Bureau would tell newspaper journalists that taxes on railroads or railroad companies were bad, and at the time journalists didn't really think to question this ostensibly independent economic think tank. It's yet another technique we still see all over today.

Biographers of Lee are often torn over whether or not he was well intended. His lofty "principles of PR" are often pointed to as ethical touchstones for the industry. We cannot speak to the intentions of a long-dead man, but we can think about the many things he said and wrote himself about the industry he helped to create. Lee was an absolute believer in the power of business to solve problems, of the free market to deliver solutions. His counseling of Hitler was more driven by wanting German and American businesses to keep trading than anything else; ditto his efforts to establish trade relations between the U.S. and Russia. He figured you don't go to war with your trade partners. As a spokesperson for and counselor to industry, Lee always encouraged telling the public the truth, but he also had a very...let's say unusual...understanding of the word "truth" and spoke often about his job being to deliver “my interpretation of the facts" to the public.

Carl Byoir

Born to Polish Jewish immigrants in Des Moines, Iowa, Carl Byoir started his career like a lot of the PR men we've profiled here: working for a newspaper. At just 17, he was appointed managing editor of his local newspaper, The Waterloo (Iowa) Times-Tribune. He put himself through college and started a savings account with money he won from various writing and debate contests. While at school, he helped publicize various shows the drama program put on, and staged his first big public relations campaign—to get himself elected manager of the college yearbook. He graduated from the University of Iowa in 1910 and enrolled at Columbia's Law School.

Here's a plot twist if there ever was one: Byoir is largely responsible for bringing the Montessori approach to early childhood education to the United States. On the train on his way to law school one day, he read a magazine feature about Maria Montessori and her approach to kindergarten. He thought American mothers would love this approach, so he took a leave of absence from law school and went to study under Montessori in Italy for a few weeks so that he could become the U.S. expert on her system. Then he bought the American franchise for the system and started a small publishing company called The House of Childhood. Through that company, Byoir sold both Montessori curricula and training materials, and a magazine for children.

Byoir's children's magazine, John Martin's Book, did okay but never succeeded financially the way he'd hoped. He figured it was because he didn't know enough about circulation and ad sales, so he applied for an apprenticeship at Hearst to learn more. He had a real knack for the publishing business and seemed to dominate every department he moved through, ultimately winning a job as circulation manager for all the Hearst publications.

The Creel Committee

Byoir was still at that job at Hearst when the government's propaganda arm, the Committee on Public Information, came calling. One year before Edward L. Bernays joined the Committee on Public Information, Byoir was called to Washington by George Creel, the journalist-turned-political campaigner who ran the Committee. His combination of a law education, sales, advertising, publishing and journalism skills made Byoir the perfect right-hand man for Creel.

Byoir's first challenge for the Committee was just getting things printed. The Committee had the content for its pamphlets and newsletters, but no way to get them made thanks to a backlog of wartime print jobs. Byoir drew on his experience at his college yearbook, remembering that smaller printers that mostly worked on mail order catalogs had a slack period in early spring and fall. He signed a contract with one, got their materials printed and saved the Committee 40 percent. These sorts of feats earned Byoir the nickname "the miracle man."

Byoir also helped to recruit and train men who were influential in various communities to become part of the Committee's 4-Minute Men program—the original influencers, these guys gave prepared 4-minute speeches in support of the war effort at various parties, functions, silent film screenings, and conventions. Byoir also helped the Committee reach America's many immigrant communities, placing ads in various foreign language newspapers, enlisting 4-Minute Men in these communities, sending notices directly to people's mailboxes, and creating film reels, all of which helped to increase the number of men enlisting in the military by millions.

Byoir gained infamy during the 1930s for his role in helping Cuba and then Germany build their tourism industries. He created the March of Dimes as part of an effort to burnish the image of one terrible rich guy. His work with foreign clients was critical in understanding how to sell American ideas and ideals to other parts of the world, a task that became a huge part of his work for the Creel Commission. Amidst it all, Byoir also created the model for PR billing and staffing that still exists today.

He was one of only a few Committee members kept on after the war to handle post-war messaging, eventually leaving in 1919 to start his own PR business, and hiring Edward Bernays to help with his very first client, The Lithuanian National Council in the United States. The Council wanted Byoir's help getting the U.S. Senate to officially recognize Lithuania as a free and independent nation, and he delivered. But unlike Bernays, Byoir wasn't immediately great at running a PR business. He went back to what he knew best: sales and advertising, working for Nuxated Iron.

Cuba

It was, of all things, sinus infections that drew Byoir to Cuba in the late 1920s. The warmth and humidity cured him of infections that had been life-threatening living on the U.S. East Coast, and Byoir decided to stay. He leased two newspapers and set about looking for ways to increase circulation. Rather than try to figure out if the techniques he'd used back home would work here, Byoir decided to focus on getting more American tourists to Cuba. He signed a deal with then-president Machado that if he could increase American tourism to Cuba spending his own money, the government would sign a five-year, $300,000 contract to hire Carl Byoir & Associates as the PR firm for the Cuban government. They doubled American tourism to Cuba in just one year and became the country's official PR firm. By 1932, locals were threatening to kill him over his association with Machado, and Byoir fled back to New York to set up shop there again.

Later, Byoir's work for the German government, trying to encourage more American tourism in Germany, combined with his work for Cuba, would draw raised eyebrows and a trip to the House Un-American Affairs Committee. He was acquitted of any wrongdoing in both cases, but it cast a shadow on his reputation.

March of Dimes

Like Ivy Lee before him, one of Byoir's anchor clients was a shady rich guy who needed help improving his reputation: Henry L. Doherty. Doherty had made most of his millions cutting corners during the Depression, and Byoir was looking for a way to rehabilitate his rep when he got a call from a charity affiliated with Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Warm Springs Infantile Paralysis Foundation wanted a multi-million-dollar donation from Doherty, and Byoir thought it was a great idea.

He designed a fundraising event to make news that would make his client look good. Every person and group involved in the event was part of the sell, for Byoir. He brought in third-party influencers like the Elks, Masons, American Legion, labor unions, business organizations, Kiwanis, Booster and Exchange clubs. And to boost attention, they planned the event for the President's birthday.

Byoir personally called every newspaper publisher in the U.S. and asked them to nominate a local FDR Birthday Ball chairman. Those nominations also made news. The Birthday Ball turned into an annual event, but was eventually rebranded to The March of Dimes. Later in his memoir, Byoir mused:

When you set out to influence and persuade people to action, when the campaign is tremendous, nation-wide [sic] in scope, don't think that it just happens; something has to be done to get millions of people to think the thought you want them to think and then to get them to act on that thought."

The A&P

In the late 1930s, at the height of the Depression, legislators began floating the idea of taxing chain stores. The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P) went to Byoir for help combating the idea. Byoir used a relatively new technique—opinion polling—to determine that people were generally in favor of taxing chain stores, but were unaware that those taxes would probably increase the cost of the food they were buying. Byoir set about getting that information out and effectively turned the tide. His clients were ecstatic...until the campaign resulted in an anti-trust investigation in the early 1940s.

The Railroad-Truckers Brawl

In the early 1950s, truckers in Pennsylvania wanted to change the laws around weight maximums for trucks. The railroads didn't like this idea because they figured trucking companies would steal railroad clients. Eastern Railroad hired Byoir & Associates to help defeat the proposal and Byoir did his thing. He created ads about how terrible truckers were and created unfavorable ads about truckers and generated anti-truck studies and white papers to distribute to reporters. He also sent journalists an advance copy of Maryland's State Road Commission's test which reported the negative effects of differing truck axles on highways. The bill was vetoed immediately... and Byoir & Associates once again found themselves facing an anti-trust investigation. They would eventually be cleared in 1961, but Byoir himself wouldn't live to see it.

Edward Bernays

Edward Bernays gave himself the title "The Father of Modern Public Relations," a clever way to erase the contributions of those who came before them and solidify his legacy. Clever because it was technically true: he created the term "public relations" after the Germans had, as he put it, "given the word propaganda a bad name."

Bernays is better known than his predecessor Ivy Lee, in part because Lee died so young, while Bernays lived to over 100 and continued to work, write, and think about PR almost to his dying day. He's a central figure in the documentary The Century of the Self, which provides fascinating insight into who Bernays was as a person and what he believed, namely that the masses needed to be controlled because most of them were too stupid to know what was good for them, and certainly to know what was good for the country.

Bernays's uncle was Sigmund Freud—on both sides, in a bizarre and some might say Freudian twist (Edward's mother was Freud’s sister, and Freud was also married to Edward's father’s sister). Bernays grew up in Vienna, hearing all about Freud’s theories on the deeply buried human impulses that drive behavior. As a young man, he was very interested in the performing arts, particularly ballet and theater and he began to work in that world as a new sort of publicity man, less focused on posters and ticket sales and more on making his clients a major topic of conversation at dinner parties. His work in that realm attracted the attention of George Creel, who was heading up the government's WWI propaganda effort, and Bernays headed to Washington to join the effort.

It was here that he saw the real power in propaganda and became a bit drunk with his own ability to manipulate the masses. Bernays chaired the Committee on Public Information's Export Service, meaning his job was to help sell Europe on the idea of America as an ally and a savior. There is very little documentation of what Bernays actually did during WWI, but unlike his predecessor Ivy Lee, Bernays was all about promoting himself as much as his clients, and he spun a narrative for decades that he was integral to the Committee's success.

Bernays and Lee represent two archetypes that we see over and over again in PR history, with Lee preferring to operate behind the scenes and Bernays seeing value in being as visible himself as his clients were. Which is why, in addition to crowning himself the father of public relations and playing up his role in the Creel Commission, Bernays also consistently referenced his uncle and his relationship to him, creating the impression that he had a special understanding of human psychology and behavior by virtue of that family connection.

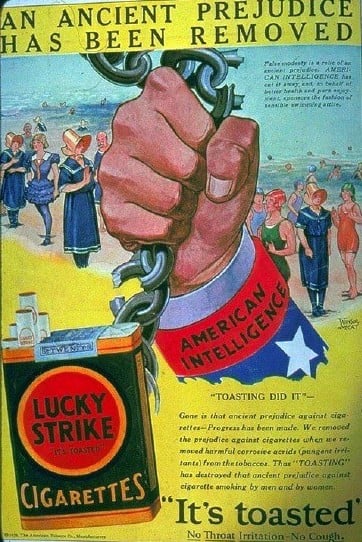

If Bernays was good at selling himself, he was also very good at delivering big wins for his clients. And he fundamentally changed many aspects of American society without Americans really knowing it. His list of successes includes:

Earl Newsom

There are two types of PR guys, the ones who make themselves a central character in the story and the ones who work their magic quietly behind the scenes. Earl Newsom was the latter sort to the extreme. His name only really comes up in the context of other PR legends talking about what a genius he was. But while he kept an extremely low profile, Newsom was possibly the most influential PR guy of the 20th century, working for corporate giants like Ford, GM, Campbell's Soup, Standard Oil of New Jersey (which later became Exxon), and many more.

Newsom was born in Wellman, Iowa, and graduated from Oberlin College in 1921. He took time off of college to serve as a Navy pilot in WWI. His approach to the job was not at all about press releases or talking to journalists, instead he really focused on truly managing the relationship between a company or an industry and the public. He was a trusted advisor to CEOs, helping them navigate crises and keep a constant, close read on the public. Newsom also collaborated often with Elmo Roper, who pioneered market research and polling. From the late 1930s onward, Roper based the majority of his PR plans on polling reports from Roper.

Standard Oil of New Jersey

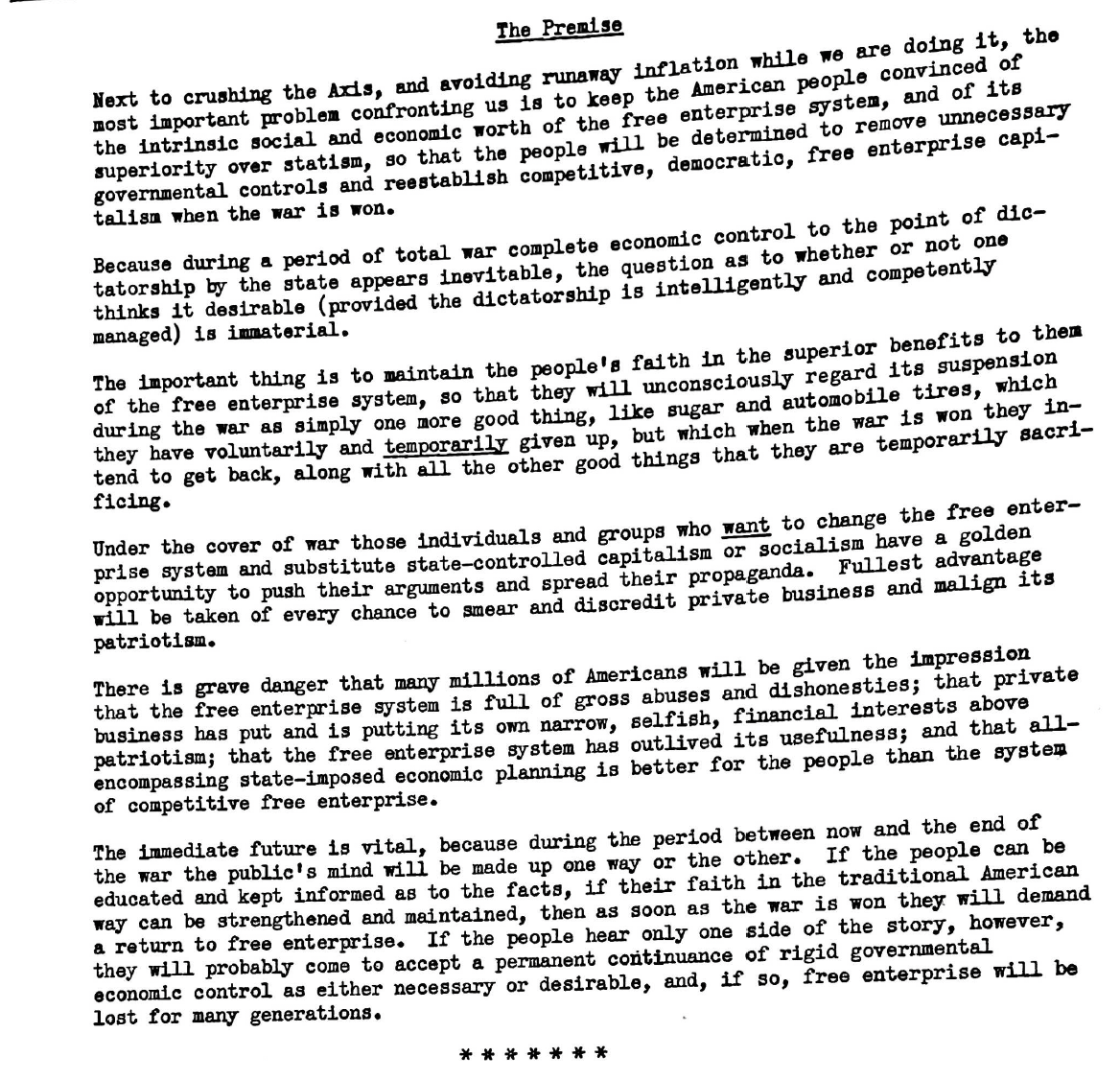

Earl Newsom worked for Standard Oil of New Jersey, which eventually became Exxon, from the early 1940s til he retired in the mid-1960s. He managed every aspect of the company's public persona, from seemingly inconsequential decisions like whether or not a VP should accept an award from a PR college for his work on education (Newsom said no, lest people think Standard's investments in universities were just a PR stunt) to the company's approach to developing oil fields in South America and the Middle East to cross-industry strategies for shaping how Americans think about the economy. One of the most fascinating documents Newsom left behind was a strategy document from early in the year in 1945. WWII was coming to a close, and Newsom was concerned—not that the Allies would lose, or that the companies he worked for would have to find new revenue streams once wartime purchasing ended, but that Americans had grown so used to the government taking care of them that they might turn away from the benefits of free enterprise. At the time, Newsom was working for Standard Oil of New Jersey, Ford, and GM, but the plan included non-clients too, it was an all-hands-on-deck moment for industry.

"Next to crushing the Axis, and avoiding runaway inflation while we are doing it, the most important problem confronting us is to keep the American people convinced of the intrinsic social and economic worth of the free enterprise system," he wrote. "And of its superiority over statism, so that the people will be determined to remove unnecessary governmental controls and reestablish competitive, democratic, free enterprise capitalism when the war is won.”

"There is grave danger that many millions of Americans will be given the impression that the free enterprise system is full of gross abuses and dishonesties," he continued. "That private business has put and is putting its own narrow selfish, financial interests above patriotism; that the free enterprise system has outlived its usefulness; and that all-encompassing state-imposed economic planning is better for the people than the system of competitive free enterprise."

General Motors

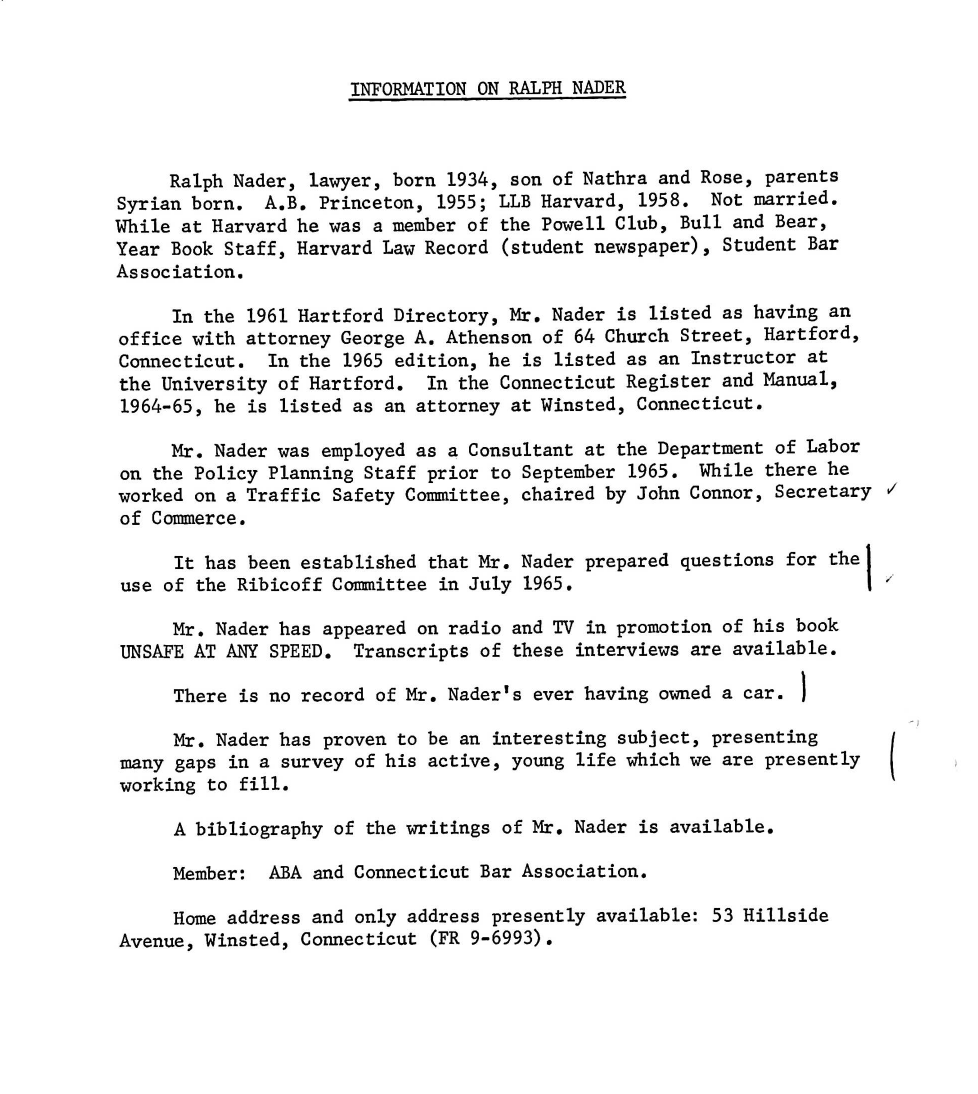

Newsom also worked for General Motors in the 1960s during a particularly tough time for the company, when it was dealing with the fallout of Ralph Nader's seminal 1965 book, Unsafe At Any Speed. More so than the book itself, GM faced public backlash and a Senate investigation over its handling of the book, which included gathering opposition research on Nader and even trying to entrap him with young women. Newsom counseled GM's executives through the Senate hearing and apology for the Nader debacle, and through various skirmishes with labor unions over the years.

Early report on Nader, prepared by Newsom’s team for General Motors

Ford

Newsom's longtime friend and collaborator the pollster Elmo Roper started pushing Ford to hire Newsom in the 40s and initially Newsom actually said he was too busy. He thought Henry Ford and his son Edsel would be too tough to manage. This is where you really see how different Newsom was from most of his compatriots in the field. He really saw himself as a close advisor to CEOs, managing every aspect of their relationship with the public. And he couldn't do that—wouldn't do it—with a difficult CEO. But in 1945, Newsom had a meeting with Henry Ford that convinced him; he set about turning the elder Ford into what he called "an industrial statesman," giving speeches, meeting with politicians, acting as a sort of ambassador for American industry to both the U.S. public and the world. Newsom counseled Ford through the highly controversial move of pulling the paid lunch period post-war, crafting and executing an internal communications strategy that painted the company as benevolent and fair, the idea of paid lunch as Communist, and the striking employees as criminals.

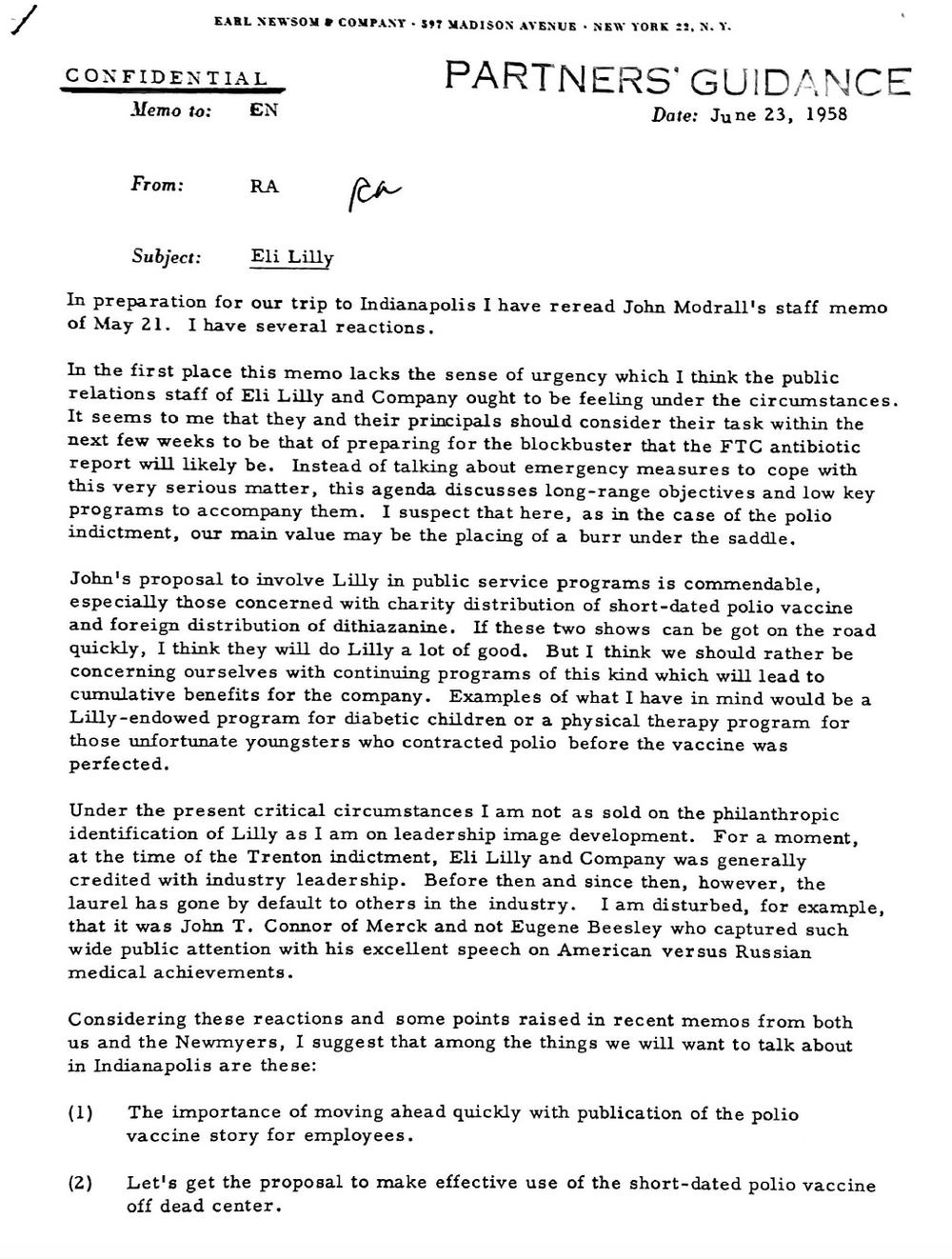

Eli Lilly

Newsom was one of the first publicists to work with the pharmaceutical industry, advising Eli Lilly for years, with a focus on pushing the idea that private enterprise and pharma profits were the key to innovation and life-saving miracles. Newsom and Lilly's other PR firm, Hill & Knowlton, would coordinate various campaigns and press pushes through the pharma trade group, the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association.

John Hill

John Hill was born on a farm in Indiana in 1890. His grandfather had been wealthy, but his father lost all the family’s money in a series of business deals gone wrong, and Hill would spend the rest of his life trying to recapture his family's status, chasing the company and approval of rich men. Like a lot of other PR legends, he started his career as a journalist. But unlike the others, he seems to have been fairly good at it. While most of the rest just spent a year or two struggling to make journalism work, Hill was a financial and business reporter for 17 years before he got into the PR game. He even started a couple of newspapers himself, although struggled to keep them afloat.

His first foray into PR came in 1920, in Ohio, when he took a gig creating a newsletter that Cleveland’s Union Trust Company wanted to send out to local executives. By this time he was the financial editor of a steel industry trade magazine … because Ohio. These jobs put him in regular contact with executives who complained to him constantly that most reporters were inept at numbers. They also introduced him to a lot of influencers and executives in the area, and eventually Hill saw a niche he could fill: helping companies explain themselves to reporters who didn’t “get it” quite as well as he did.

Hill opened up his own firm in 1927 with Union Trust and Otis Steel as his first clients. Because Hill was well-liked by local executives, word spread fast and within a couple months he had built an impressive roster that included United Alloy Steel, Republic Steel and Standard Oil of Ohio.

The Standard Oil account was an important win for Hill because he was a huge fan of Ivy Lee, the country's first PR guy. Lee may have tapped Edward Bernays as his successor, but John Hill was probably a more natural fit. Hill hated how flashy Bernays and many of the other PR guys of his day were. He preferred Lee’s distinguished southern demeanor and emulated it. Like Lee, he preferred to stay behind the scenes … although Hill took it to an extreme, almost never appearing in the press. When he did show up anywhere, it was always in a conservative suit, clean shaven, hair slicked back, wire-rimmed glasses.

But just when his business was starting to take off, the financial markets came crashing in on themselves… The PR industry was actually one of the few to benefit from the Depression. In Hill’s case, when his first client, Union Trust, went under, he invited one of its top executives, Don Knowlton, to join him in March 1933, launching the firm Hill & Knowlton. His steel and oil clients had weathered the financial storm fairly well, and Republic Steel had just scored the firm a whale: the American Iron and Steel Institute—the trade group for the whole steel industry. They requested that Hill and Knowlton open up a New York branch near their headquarters in the Empire State building. That same month, Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office, and the new firm was only too happy to oblige.

That same month, Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office, with promises of a New Deal. Hill hated this idea, and so did most of his clients. Standard Oil had him write up an advertorial assuring people American business would be okay, and his steel clients had the firm cranking out pamphlets emphasizing the great relationship between steel workers and their managers.

“Workers in the steel industry represent a high degree of skill and intelligence,” it reads. “Most of the managers of the industry have worked their way up from the ranks. For a long time the industry has been distinguished by harmonious relationships and collective cooperation between employees and employers.”

The reality, of course, was that steel workers and their bosses had been fighting for a long time. And America’s big steel companies had done everything they could to repress unionization. It was a fight that went beyond the industry itself--as the largest industry and the largest employer in the country at the time, the steel industry viewed itself as sort of the last, best defense against unionization. A protector of American business, defender of bosses everywhere. They were helped in their efforts by near constant concern about creeping Communism in the U.S., starting with the 1919 Red Scare and continuing for decades.

Anti-union pamphlets Hill and Knowlton made for Republic Steel highlighted how union shops actually infringed on workers’ rights. “A closed union shop denies the right of the individual worker to make his own choice as to whether he wishes to belong to a union,” one notes. Another Hill + Knowlton client, the National Association of Manufacturers, one of the earliest industry trade groups went beyond pamphlets to sponsor a weekly, pro-business, anti-New Deal radio drama called the American Family Robinson.

But after more than a decade of suppression, the labor movement was gaining steam again in the 1930s. A few years after opening his firm’s New York office, John Hill faced his first big challenge in P.R. And just like with his hero Ivy Lee, it came in the form of a violent labor strike.

Steel workers were starting to band together by 1936, forming the Steel Workers Organizing Committee within one of the country’s biggest unions (the CIO), officially freaking steel bosses out. The American Iron and Steel Institute put Hill and Knowlton on the case, and they wrote up full page ads with a manifesto for the industry. The ads suggested that outside agitators had coerced employees into joining the union; that the union amounted to forcing a worker to pay for a job; and that the industry, and therefore its employees, would be irreparably harmed by a work stoppage right in the midst of its recovery from the Depression. On the last day of June and the first of July 1936, the trade group sponsored full-page ads in 382 newspapers in thirty-four states.

But the unions persisted … and actually most of the industry was willing to negotiate. In 1937 U.S. Steel agreed to recognize the unions and negotiate a contract, which made it more difficult for other companies to resist. Eventually even the trade group backed down. But there was one holdout: Little Steel, an umbrella group that included smaller independent steel companies, was having none of it. Led by a man named Tom Girdler, president of Republic Steel, they refused to have any sort of contract with the union. Then in May 1937, Girdler was elected president of the steel industry trade group. Apparently, he had been stockpiling weapons in the months leading up to his takeover of the industry group, and he fully intended to crush this whole union idea once and for all. A strike began at the Republic Steel plant in Chicago the day before Girdler’s election, and within four days he had turned it into an armed conflict.

The union quickly branded the event as the Memorial Day Massacre, holding a mass funeral in Chicago attended by hundreds of working-class residents. Another riot broke out at the Republic plant in Youngstown, Ohio, that June, ending with two dead and forty-two injured.

The FDR administration was having none of it. In October, the National Labor Relations Board ordered the companies to reinstate more than 7,000 workers with back pay.

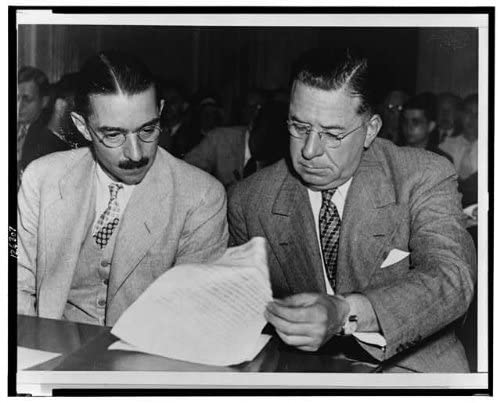

Then the Senate launched investigations into the steel boss’s methods. Because of Hill’s involvement in pushing anti-union messages and ads in newspapers, he was caught up in the investigation, too. Senator Bob LaFollete discovered that not only had Hill placed ads, he had successfully bribed a journalist. George Sokolsky, a columnist for the New York Herald Tribune, frequently wrote about free enterprise and anti unionism in magazines, like the Atlantic Monthly. From 1936 to 1938, Sokolsky received $29,000 from Hill and Knowlton to write anti-union articles for the steel industry trade group. It worked: he wrote stories in prestigious newspapers and magazines about how the riots were all the union’s fault … never disclosing his connection to Hill and Knowlton or the steel industry. Sokolsky also regularly ranted on the radio for the National Association of Manufacturers and various other pro-business groups. Here he is ranting about that terrible socialist policy: social security.

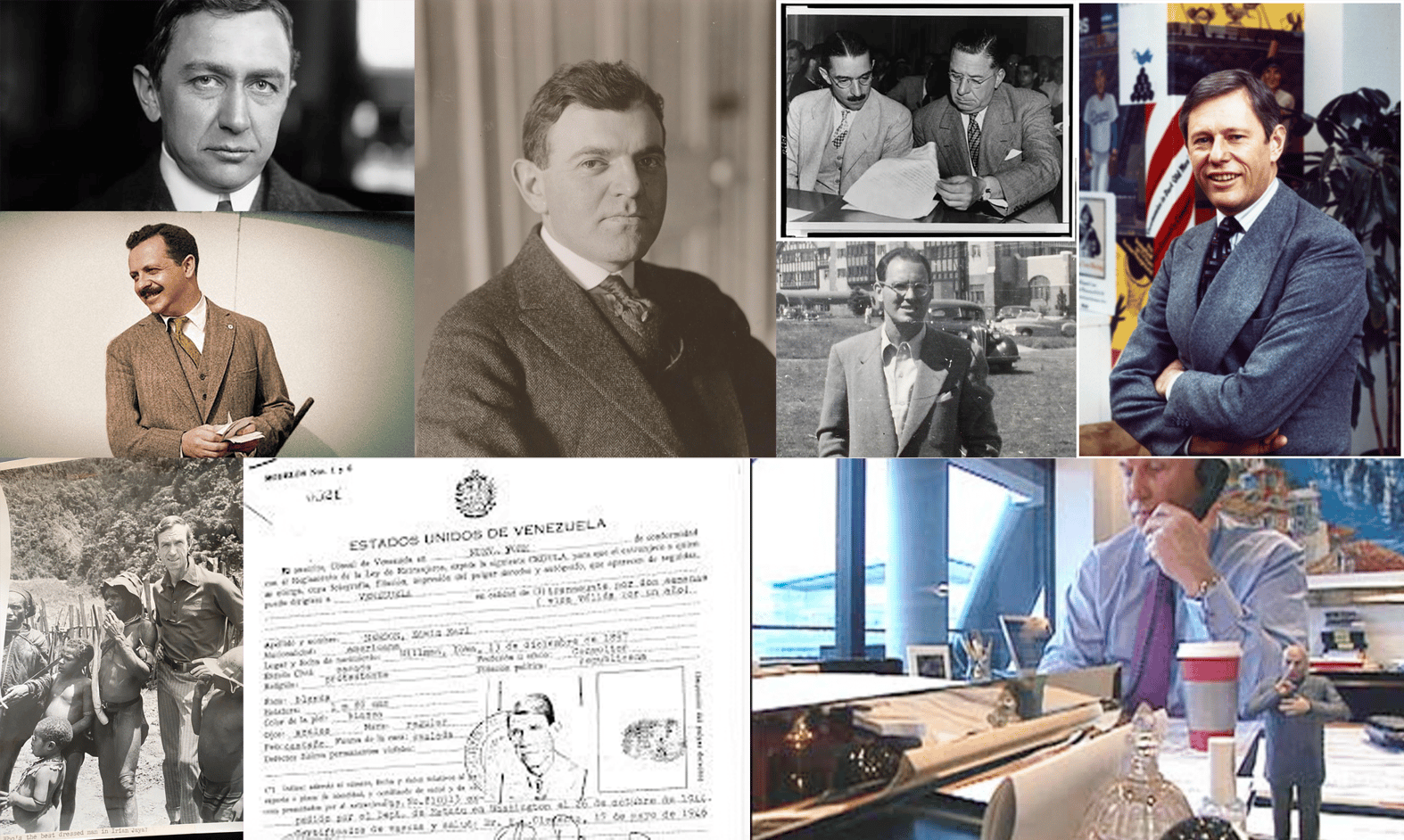

Hill (right) and his business partner Don Knowlton testifying before the U.S. Senate.

World War II had just put an end to years worth of labor strikes in steel mills. John Hill was hired to help the industry through it all, but his work on that front was basically a failure. Not only had his clients lost the war with labor, but their goonish tactics had been outed in the press. They looked just like the evil bosses they were pretending not to be.

Still, a lot of people would have been fired for bungling the labor strikes so thoroughly. Hill had read the room entirely incorrectly. And not only that, he’d gotten busted bribing a journalist. But by this point, the steel and oil barons who made up Hill’s clientele considered him a friend, a trusted confident, more than someone they employed. He was routinely described in the press as a “trusted counselor to industry”. And he spent almost as much time managing how his clients saw him as how the public saw them. It was a big part of the Hill & Knowlton strategy in general. Hill and his execs didn’t just manage accounts, they attended the leadership and board meetings of their big clients and weighed in on corporate policy.

By this point, Hill had also learned a very important lesson: his job wasn’t to sell the public on any particular product, company or industry. It was to sell Americans on the importance of American business in general, and particularly big business. He was pushing ideology, creating social license for American industry.

That meant working in Washington, too, of course. Shortly after the war, Hill and Knowlton became the first PR firm to have staff dedicated to public policy work. The Washington office didn’t have its own accounts; it existed solely to handle government relations for the firm’s New York and Cleveland clients. By this point that meant they had their hands in everything from energy policy to agriculture and all points between, for clients like Texaco, Marathon Oil, Coca Cola, Monsanto, and a big new client: the Tobacco Industry Research Committee.

The Tobacco Industry Research Committee

The Tobacco Industry Research Committee (TIRC), is a really good example of the type of strategy Hill would typically recommend for industries, and a good example of how the fake-expert strategy deployed by Lee and Bernays became science denial. It also illustrates the long-term link between tobacco and oil. Not only did Hill have oil clients early on who informed some of his work on tobacco, and vice versa, but he often brought them together in the same trade groups. RJ Reynolds, for example, a key member of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee, also had their research arm join the American Petroleum Institute, also a client of John Hill’s by this point. And then there was the fact that the oil companies helped come up with cigarette filters for the tobacco companies...that's why they were co-defendants in the tobacco litigation in the 90s. That and the fact that gas stations were a primary retail outlet for cigarettes, so companies in the two industries would often partner up on advertising campaigns.

While all of this is happening between the oil guys and the tobacco guys in the background, Hill and Knowlton has their staff funding and sourcing research on all the other things connected to lung cancer. And they’re looking for scientists to sign on to their advisory board, but what they really need is a credible director. This was all Hill’s brainchild. The tobacco companies initially argued with him that they had already done their own research, that they didn’t need a whole new research council. But Hill insisted: they needed third party, independent research that would be perceived as more credible by the media. Eventually they gave in. In December 1953, the CEOs of all the major American tobacco companies met with Hill at the Plaza Hotel to launch the Tobacco Industry Research Committee. They needed a reputable cancer researcher as director, which wasn’t easy to find. So in the first several months of the committee’s existence, its “research” was conducted by Hill & Knowlton staffers.

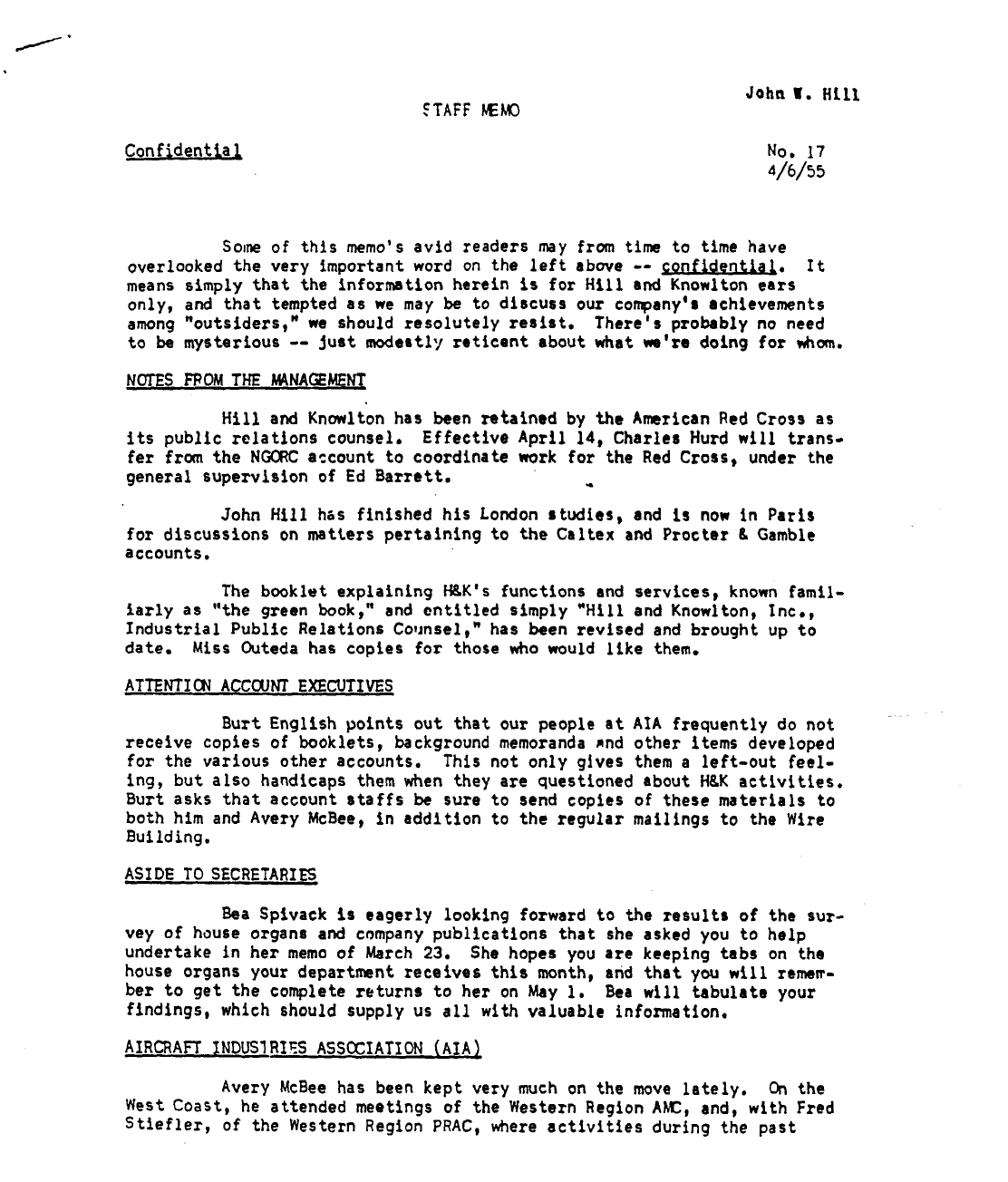

There are all these staff memos from this time where they’re giving updates on clients and the oil-tobacco connection is stark, because you’ve got updates on Texaco followed immediately by updates on the phony research committee, with lots of the same staff on both (see above).

Eventually they hired Dr. Clarence Cook Little. He went by C.C., and Hill and Knowlton proclaimed him a world-renowned cancer researcher. It was a bit of a stretch. True, Cook did have some impressive credentials. He had been president of the University of Michigan, and had worked for a year as the director of the predecessor to the American Cancer Society today). BUT, he was also a huge fan of...eugenics. So much so that he’d been pushed out at the University of Michigan over his views. And in that same year that he was at the cancer society, he also led the American Eugenics Society. But even more pertinent to his work with the tobacco research committee was the fact that he’d never actually done any cancer research. The cancer “lab” that Cook ran just raised mice for actual researchers to use. In the hands of Hill and Knowlton, though, Cook became a widely respected researcher.

By 1947, John Hill and Don Knowlton had mostly parted ways, although the firm kept the same name. Hill gave Knowlton the Ohio clients and kept the rest for himself. Over the course of his life, he turned Hill and Knowlton into the largest PR firm in the world. Although he retired in 1962, he remained very involved in the firm, going to the office daily right up to a month before he died, at the age of 86, in 1977. Hill had stayed true to his commitment to stay out of the press himself, and none of his industrial machinations were well known at the time of his death.

Harold Burson

The son of English immigrants, Harold Burson was born in Memphis, Tenn. in 1921. Like a lot of other PR leaders, Harold Burson started out as a reporter, then served as a Public Information Officer in the Army during WWII, working for a while at the American Forces Network, which was the Army radio network in Europe. After the war, he stayed on with the radio network, and was assigned to cover the Nuremberg trial. Eventually he returned to New York and launched a small PR firm, mostly working for engineering clients. By 1952 he had a handful of employees and a small office. He met ad man Bill Marsteller that year and the two of them decided to combine forces on a new firm, Burson-Marsteller. It would go on to be one of the largest PR agencies in the world.

Burson was a pioneer in the realm of crisis management, and often emphasized the importance of his clients taking particular actions, not just coming up with the right messaging. “In the beginning, top management used to say to us, ‘Here’s the message, deliver it,’ ” he's quoted as saying in the textbook Public Relations: Strategies and Tactics. “Then it became, ‘What should we say?’ Now, in smart organizations, it’s ‘What should we do?’

Burson-Marsteller’s clients included Philip Morris, Merrill Lynch, Coca-Cola, Shell, ExxonMobil, General Motors, Dow Chemical, IBM, American Express and Citicorp. The firm also served Nigeria, Argentina and Romania at times when those countries had dictators with image problems.

Tylenol

Crisis management existed before the cases Burson handled for Tylenol, but he and his firm really made it part of the PR industry, and that all started with two big problems for Tylenol in the 1980s. First, in 1982, seven people died after taking Tylenol that had been tampered with. The company moved quickly to recall products and introduce better tamper-resistant caps, and Burson moved just as quickly to make sure the public knew about it. In 1985, a similar thing happened—three people were found dead after consuming Extra Strength Tylenol capsules that had been laced with cyanide. Again, Burson and the company moved quickly to figure out exactly what had happened and assure the public it was one batch only.

Bhopal

Burson's best-known crisis management stint was for Union Carbide in the wake of the Bhopal disaster—a gas leak at its pesticide plant that killed more than 15,000 people and injured 600,000 in Bhopal, India. “We are being paid to tell our client’s side of the story,” Mr. Burson told the New York Times that year. “We are in the business of changing and molding attitudes, and we aren’t successful unless we move the needle, get people to do something. But we are also a client’s conscience, and we have to do what is in the public interest.” Burson-Marsteller pushed the company to invest in clean-up and rehabilitation efforts, and the firm focused on those efforts in the press, with Burson often insisting that Union Carbide, which paid $470 million in 1989 to settle lawsuits, had been forthright and ethical.

In 1979, Burson-Marsteller was acquired by Young & Rubicam, the advertising agency, which was absorbed by the communications giant WPP Group in 2000. Mr. Burson remained as chief executive of Burson-Marsteller until 1989, when he became founder-chairman. He continued for many years to visit company offices, mentor employees and meet clients. He died in October 2020.

Daniel Edelman

Daniel Edelman learned the tools of his trade during World War II, combating serving four years in a United States Army psychological warfare unit that combated Nazi propaganda. Returning home to New York City after the war, he had a decision to make: Return to his pre-war journalism career, or use his psy-ops skills to make his way in America’s booming post-war economy?

After a brief stint with CBS, he chose the latter, taking a job as a publicist for his brother-in-law’s record label. In 1947 he moved to Chicago to become public relations director for Toni, a hair care company with a popular home permanent kit. While at Toni, Edelman began to combine a bit of lobbying into public relations. Salon owners didn’t love the idea of women giving themselves perms at home, and had mobilized to get do-it-yourself kits banned. Edelman succeeded in convincing various state lawmakers that salon owners were going too far, and none of the proposed bans became law.

Edelman founded his public relations firm in 1952, with Toni as his first client. By 1960 the firm had 25 clients that included household names like Sara Lee, and a second office in New York. By the late 1960s, it was opening offices in New York and overseas.

The R.J. Reynolds tobacco company approached Edelman in 1977 for a proposal to help restore its image and business, in the wake of the 1971 ban on cigarette advertising.

There’s a lot of documentation on the scientists who helped tobacco firms manufacture uncertainty about the health harms of their products. As historians Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway recount in their book Merchants of Doubt, some of these same scientists went on to do similar work for Big Oil, to spin the public on the link between burning fossil fuels and climate change. t But not much has been written about the publicists who helped to craft this strategy, among them Daniel Edelman. A key part of his 1977 proposal to R.J. Reynolds was the idea of creating room for doubt in the cigarettes-and-health debate. “In our judgement, if we can convince the public that there is a real possibility that additional research can produce entirely new insights on health and smoking,” he wrote, “we can improve the industry’s own credibility.”

The proposal was a success—Edelman was still advising R.J. Reynolds in 1985, per documents in the Industry Archive at UCSF. In the document highlighted below, for example, an Edelman exec on the account is advising RJR how to handle the hundreds of internal industry documents that had, by that point, become public.

Edelman was also an early proponent and practitioner of “astroturfing”: creating fake grassroots groups, with their funding by industry obscured,, to counter real environmental and public health activism. “Edelman was genius at it,” says Christine Arena, a former Edelman vice president.

Over the past three decades, several such groups have gone on to become major players in confusing the public about climate change.“Fossil fuel industry organizations fund these fake front groups, and they give these fake front groups these perfectly innocuous names, like the ‘California Drivers Alliance’ or the ‘Washington Consumers for Sound Fuel Policy,’” Arena says, which are actually run by the Western States Petroleum Association, which is a top lobbyist for the oil industry.” Another prominent pro-industry group that tries to appear independent, the Western States Petroleum Association, is funded by BP, Shell, Exxon Mobil, and other Big Oil firms, says Arena. “It’s fake activism. It’s corporate money posing as activism. And it’s designed to undo all of the progress that real activism makes.”

E. Bruce Harrison

E. Bruce was another behind-the-scenes guru, all aw shucks Southern charm but a master manipulator of the public and the government. An Alabama boy desperate to escape his roots, he spent a brief stint as a reporter at the local newspaper before making his way into politics, first as the press secretary of an Alabama Democrat, where he even wound up helping out on JFK’s campaign.

But his favorite visitors to the Alabama Senator’s office were the corporate lobbyists. His boss had no time for these folks, but Bruce liked the cut of their jib, and the idea that business was a better way to solve problems than policy would ever be.

The chemical lobby wooed him to work for them, making him the very first “environmental information officer” ever, and almost immediately he found himself facing an enormous challenge: beating back the first wave of the environmental movement and “that damn book” Silent Spring. He lost that battle, but learned some lessons, and then went to work for a mining company that sent him off to Indonesia to set up a deal to create the world’s largest copper mine.

When he came back to D.C. in 1972, it was clear that industry had truly been caught flat footed by the environmental movement, and were struggling to regain their footing. Most modern environmental legislation was passed between 1965-1972, and the EPA was established in 1970 to enforce it all. Harrison’s old pals in the chemical industry and at the American Petroleum Institute were losing in this new world, and he was in a perfect position to help them win again—he knew business, he knew government, he knew lobbying and PR, and now he even had foreign relations under his belt. Harrison’s big idea was to combine various industries, unions and government entities together into groups that could get more done and couldn’t be traced to any one company. He created the National Environmental Development Association (NEDA), a vaguely pro-environment-sounding name that was actually a coalition of chemical, mining, oil & gas, and ag companies, along with industry-friendly politicians and unions, really anyone who had a bone to pick with the new environmental regulations.

Harrison made NEDA the first client of his new PR firm, Harrison & Associates, which he co-founded with his new wife, Patricia. Patricia was very much an equal partner in the firm, and very involved in the NEDA account. Years later she would work as the co-chair of the Republican National Committee and as a staffer in George W. Bush's state department. Her official State Department bio read, “As a founding partner of E. Bruce Harrison Company, among the country’s top ten owner-managed public affairs firms prior to its sale in 1996, she created and directed programs in the public interest comprising diverse stakeholder groups, including the National Environmental Development Association, a partnership of labor, agriculture and industry working for better environmental solutions together.”

They would monitor all proposed environmental policy, brief NEDA members, craft messaging around it and make sure the press had the industry viewpoint on things. They also lobbied members of Congress, and even testified before committees about the economic harm any new environmental regulation would do. Most importantly, NEDA helped to push the idea of balance and necessary trade-offs between protecting health and the environment on one hand, and economic growth on the other. At the same time, the global oil crisis had Americans looking for new forms of domestic energy, which not only spurred research into solar, but also into drilling in previously protected areas. Americans who had been getting into the whole clean air, clean water thing were suddenly rationing gas and getting very worried about losing the American way of life. Meanwhile, research scientists at oil companies and universities were stacking up evidence about a new, far deadlier sort of environmental impact for industry to worry about: the greenhouse effect.

In the 1980s the oil crisis became a glut and oil companies were facing the dual threat of cratering prices and looming environmental regulations. But Harrison and his compatriots had done a fantastic job by this point convincing Americans that regulation was bad for the economy and that the American way of life needed to be protected at all costs, especially with those commie bastards gaining power in Russia and China. 1989, as the world was growing increasingly concerned about global warming and regulation seemed more and more likely, Harrison brought auto makers, manufacturers, utilities, oil, gas, and coal companies together to figure out a strategy. He called it The Global Climate Coalition. And the first thing he did was get its members into the international climate meetings of scientists and politicians that were just starting. GCC members, and Harrison himself, were involved in shaping the UN Framework on Climate Change. They were there weighing in on the very first report from global climate scientists, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report in 1992. They were at the very first international climate conference, the Rio Earth Summit, pushing world leaders to embrace the idea that there was plenty of time to act on climate change, that we shouldn’t risk economic hardship to do it, and that in fact business could be trusted to do this work voluntarily. The group spent about $1 million a year from 1989-1997, the lead-up to Kyoto, in advertising (and $13 million in 1997, as the climate summit drew near). The group spent $63 million in campaign contributions during the 1990s.

By this point, Harrison had sold his firm to PR giant Ruder Finn because his wife was elected to co-chair the Republican National Committee and help steer Bush to victory. Harrison stayed on with Ruder Finn to advise on various clients, including his creation the GCC. Bush won, of course, and within weeks of his inauguration had pulled the U.S. out of Kyoto, using Harrison’s favorite argument, that acting on climate change would unnecessarily harm the U.S. economy. In a meeting with representatives from the GCC shortly after, Bush’s State Department told the group that the administration had pulled out of Kyoto at their suggestion, and wondered if the GCC had any ideas for climate policies they would support.

Patricia Harrison was rewarded for her election help with a plum assignment in that very same Bush State Department. Bruce went on to create the whole sustainable business ecosystem, earning him the nickname, “the godfather of greenwashing,” which he hated. He eventually became a professor at Georgetown and Patricia was hired as the President of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the public-private partnership that oversees government funding of public media in the U.S. Some critics voiced concern at the time that her time as RNC co-chair would make her too biased for the position. No one knew that she had also helped create the myth of “clean coal,” or that she and her husband were, as one sociologist puts it, “the intellectual parents of climate denial.” Patricia Harrison remains in that position today. E. Bruce Harrison died in January 2021, and was eulogized by national papers as a “pioneer in environmental communications.”

Herb Schmertz

Like Daniel Edelman, prior to his PR career, Schmertz worked in military intelligence. He also helped run JFK's presidential campaign, and worked as a labor lawyer for a few years. But he's best known for his decades-long stint as VP of Public Affairs for Mobil Oil.

In that role, Herb Schmertz brought many new PR tactics to the oil industry and the world; he invented the advertorial, bullied journalists into false equivalence (what he called “creative confrontation”), and pushed for the first big corporate personhood case—long before Citizens United—back in the 1970s. He also coined the term “affinity of purpose” marketing to describe Mobil’s longtime funding of Masterpiece Theatre and various other PBS programming, which helped to establish Mobil as “the thinking man’s oil company.”

But Schmertz didn't take credit for many of his tactics. In his book Goodbye to the Low Profile, a sort of handbook for corporate PR in the 80s, he said he had merely brought the aggressive tactics of political PR to business PR—Schmertz was forever telling corporate PR folks that their approach of being nice to journalists would never get them as far as his approach of shouting at them and accusing them of bias any time they left out his company or industry's point of view. Sadly, he was right. Bullied by flaks like Schmertz, the media largely retreated into the practice of false equivalence, and a manufactured frame of "objectivity" in which there are two equal sides to every story.

Collected below are archival videos of Schmertz, and contained within our “Schmertz Documents” are examples of the advertorials he distributed for Mobil (in numerous interviews he refers to them as “pamphlets” and to The New York Times as an excellent distribution system for the company’s pamphlets), as well as speeches Schmertz gave, transcripts of interviews with him, and various internal documents from his time at Mobil Oil.

Eyes on the Media Series

In 1982, CBS 60 Minutes brought together business executives, journalists, and Herb Schmertz as the PR guy, for a panel discussion on whether the media treats business fairly. There were four episodes:

Other interviews

Herb Schmertz interview with the Museum of Public Relations:

CSpan: Roundtable on Corporate Philanthropy This is a fascinating window into how Schmertz viewed corporate giving. In a nutshell: there's no such thing as altruistic corporate philanthropy, nor should there be. Corporations should align their philanthropic work with their bottom lines.

Rick Berman

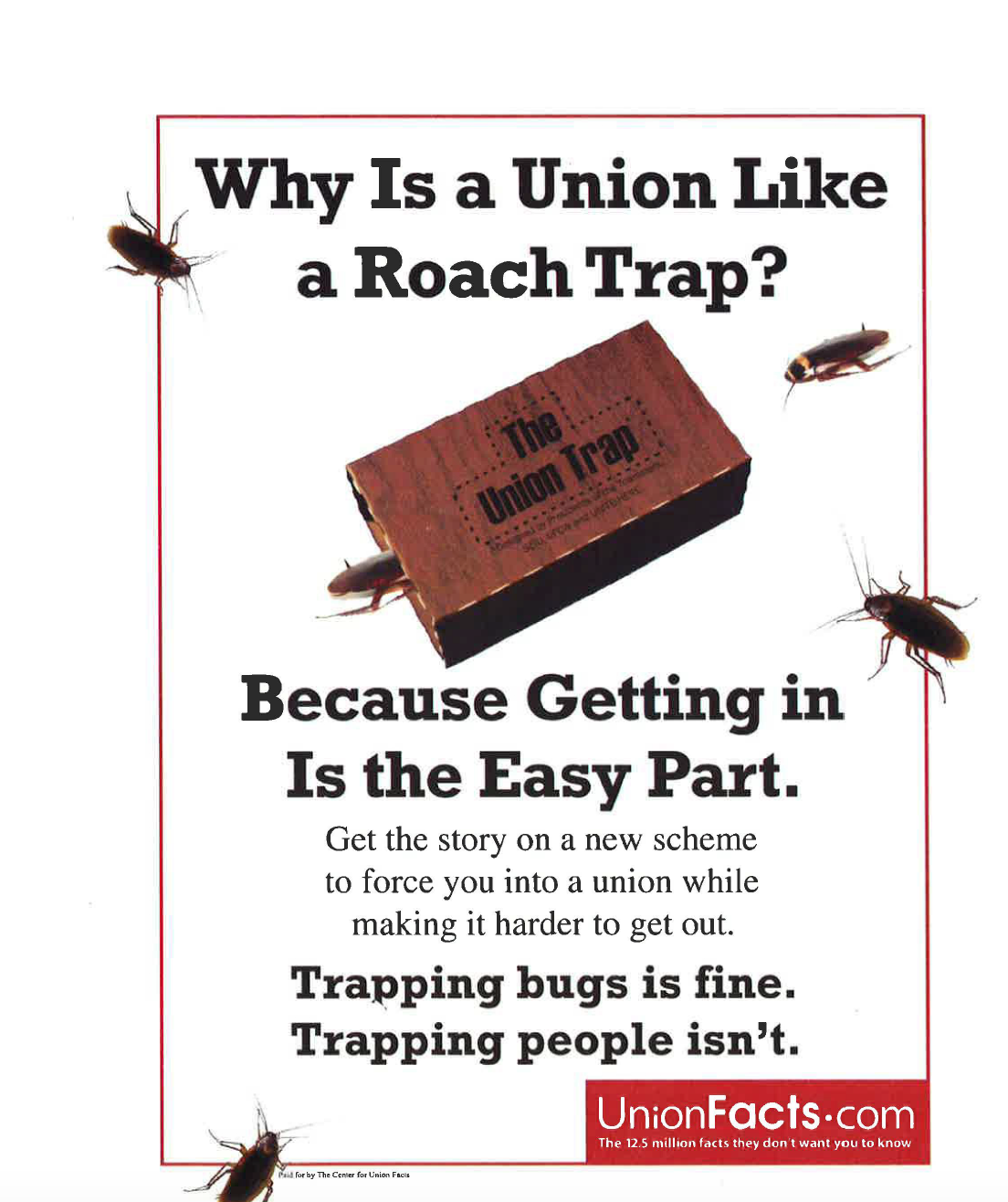

A PR exec and lawyer, Berman is best known for his "win ugly or lose pretty" approach to politics. While a lot of PR execs shy away from overt campaigns or playing dirty, Berman has built his reputation on such tactics, starting with the tobacco industry in the 1990s and now including the food and beverage industry, oil and gas, chemical companies, plastic manufacturers, and anyone who hates unions. He runs a network of front groups and think tanks funded by industry groups, companies, and rightwing foundations.

In 2014, a tape of Berman at an energy industry conference was leaked to The New York Times. In his talk, he detailed his strategy, not only for that industry, but in general.

Public judgment is when the public decides that they want to vote for somebody or not vote for somebody even across party lines based on some facts. Facts are most important, and public judgment goes deeper than public opinion. When you achieve public judgment about something, especially something that you are not in favor of: you're willing to tax it, you're willing to ban it, you're willing to put warnings on something. That's when you get public judgment, and the political process won't go that far until there is public judgment about something.

In 1987, Rick Berman founded Berman and Company, a full-service research and communications firm, with seed funding from its anchor client, Philip Morris. Prior to that Berman was employed as an Executive Vice President for Pillsbury, labor attorney for Bethlehem Steel and The Dana Corporation, as well as Director of Labor Law for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. In 2007, a 60 Minutes special on Berman dubbed him "Dr. Evil," a nickname that's stuck over the years.

Berman's forte is astroturfing. He runs a wide range of front groups, including the Center for Consumer Freedom, the Center for Union Facts, Employment Policies Institute Foundation, Center for Organizational Research and Education, and campaigns like Big Green Radicals (against environmental organizations) and Teachers Unions Exposed.