“If you're doing civil disobedience, you have to accept being found guilty as a sort of hazard,” Gail Bradbrook told me in the autumn from a comfortable sofa in her sitting room in Stroud, a small town in the picturesque Cotswolds hills in southern England.

West Yorkshire-born Bradbrook has long been a campaigner, starting with animal rights and growing to become deeply involved in broader issues of environmental, social and economic justice. But she is best known for climate activism: Bradbook co-founded Extinction Rebellion with a small group of like-minded people back in 2018.

Angry at the UK government for its lack of action in curbing national greenhouse gas emissions, Bradbrook and her fellow activists took aim at HS2, a high-speed rail line initially promised on the basis that it would speed up journeys between London and northern English cities. Despite being a public transport project, HS2 attracted huge criticism from environmentalists distraught about the destruction of ancient woodland it involved. They argued that its spiralling costs could be better spent elsewhere.

In 2019, Bradbrook went to the UK Department for Transport’s headquarters in central London and climbed onto the roof of a glass canopy. Armed with a hammer and chisel, she smashed a window before being lifted down by a cherry picker, handcuffed and taken into police custody.

During the four years in which Bradbrook has waited for a resolution to her case, the political and judicial atmosphere in the UK has changed dramatically. Parliament has passed what Amnesty International describes as “draconian” laws restricting protest, the police have arrested hundreds of activists and laid charges that have fewer legal defenses and judges are restricting the kinds of arguments that can be made in court.

It has never been easy for activists to make the case in UK courts that their actions were justified. But it has been possible.

In 2008, six Greenpeace protesters were acquitted by a jury of criminal damage after scaling one of the 200-metre chimneys of Kingsnorth power station in Kent in response to energy firm E.ON’s attempt to build the UK’s first new coal-fired power station in 20 years.

The protestors said they had a ‘lawful excuse’ for their actions because the damage caused would protect other people’s property from the effects of climate change. That argument made that year’s list of top influential ideas in the New York Times.

The action also helped the government firm up its climate commitments. E.ON subsequently abandoned the plan, Kingsnorth was demolished and the UK now generates only a tiny proportion of its electricity from coal.

Dr Steven Cammiss, associate law professor at the University of Birmingham, said protestors are trying to fill a gap in the democratic process through direct action, and trials are a logical extension of that work.

Extinction Rebellion supporters march down Constitution Hill towards Buckingham Palace and the River Thames in April 2022. Credit: Alisdare Hickson /Top photo: Activists protest the Police, Crime and Sentencing Bill in January 2022/ Credit: Alisdare Hickson

Things began to change after Extinction Rebellion burst onto the scene. In spring 2019, the group succeeded in getting droves of people onto the streets of London in an unprecedented display of climate solidarity. Over a thousand were arrested.

These actions changed the public and political mood around climate change; concern in the UK about the environmental crisis grew in the later half of the 2010s, parliament declared a climate emergency and the country set its first net zero target in the 12 months after Extinction Rebellion launched.

But the movement also sparked a backlash. In 2019, the same year the UK government set its net zero target, think-tank Policy Exchange, a UK member of the international Atlas Network, published a report describing Extinction Rebellion as “an extremist organisation seeking the breakdown of liberal democracy and the rule of law” and recommending that the police response to protest be “more proactive.” The report’s authors, including Richard Walton, former head of the Metropolitan Police Counter Terrorism Command who spent the majority of his thirty-year policing career focused on counter-terrorism, also recommended legislative changes. “Legislation relating to public protest needs to be urgently reformed in order to strengthen the ability of the police to place restrictions on planned protest and deal more effectively with mass law-breaking tactics (including incitement and conspiracy offences) such as road and bridge blocking, aggravated trespass and criminal damage,” they wrote.

UK politicians and conservative media outlets began to repeat that framing—and, in 2022 and 2023, parliament passed two pieces of legislation giving law enforcement agencies much greater powers to stop protest tactics deemed "disruptive". Civil liberty campaigners said these new laws were aimed at crushing peaceful protest and UN special rapporteur Fry described what "appears to be a direct attack on the right to the freedom of peaceful assembly". The government has since pushed through even more contentious rules making it easier for the police to put conditions on protest; campaign group Liberty recently filed a High Court challenge against this “constitutionally unprecedented” move because it bypassed parliamentary scrutiny. In the summer of 2023, at a Policy Exchange garden party, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak thanked the organization for its help with these legislative changes.

The police, whose approach to protest has become highly politicized under two successive right-wing home secretaries, have used their new powers hundreds of times in response to protests against new oil and gas production in recent months, according to the Guardian, charging activists under one of the new laws, the Public Order Act, which prohibits interference with the use or operation of key national infrastructure.

Civil injunctions against activists are also increasingly being used by organizations like National Highways, a government-owned company which runs major roads in England, to preemptively block protest action. Even those who do not breach these injunctions but are named on them are finding themselves burdened with fines as businesses seek to recoup their legal costs.

Want to listen to this story? Click play below:

Meanwhile, activists who actually break the law are finding it more difficult to defend themselves in court, and some are getting significant jail time. Last year, Morgan Trowland and Marcus Decker climbed a bridge over the river Thames to protest the UK’s approval of new oil and gas licences, stopping traffic for a day and a half. They were given prison sentences of three years and two years and seven months respectively for causing a public nuisance. When the two men tried to appeal, judges acknowledged the “long and honourable tradition of civil disobedience on conscientious grounds” and that the sentences went “well beyond previous sentences imposed for this type of offending”. But they ruled the jail terms were not excessive.

Ian Fry, the UN’s rapporteur for climate change and human rights, recently expressed concern about Trowland and Marcus’ sentences, saying he was worried about “the exercise of their rights to freedom of expression and freedom of peaceful assembly and association” and warning they might breach international law.

Dozens of climate protestors have since been imprisoned in the UK for everything from causing a public nuisance by climbing gantries over the M25 - the country’s busiest motorway - to breaching bail conditions by continuing to take part in climate protests.

The clampdown is not limited to climate activism. In 2022, a jury acquitted four Black Lives Matter protesters of criminal damage for toppling a statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol and throwing it into Bristol Harbour. The decision was hailed by anti-racism campaigners as a “huge step in getting the UK to face up to its colonial past”.

But the government referred the matter to the Court of Appeal (on the same day Policy Exchange released its similarly worded briefing on the case), which subsequently ruled that protesters accused of high-value criminal damage cannot rely on the European Convention on Human Rights.

Legal experts say this ruling deliberately dismantles a key principle established in a 2021 case against arms protestors, that arrest and prosecution of non-violent civil disobedience must be proportionate. It means defendants in similar future trials - including environment-related ones - will not be protected by the convention’s rights to freedom of thought, expression and assembly.

Michael Mansfield KC, a respected human rights and civil liberties lawyer who spent most of his working life in the Old Bailey, sees a “pincer movement” taking shape between the political and judicial systems to suppress non-violent direct action.

“It’s a form of dissent which they see as a threat, because the energy and oil companies are right at the heart of capitalist expansion and growth. It’s a reactionary political environment set against a public that are becoming increasingly aware,” he said.

While not every crime has a precise defense in law, however, judges have discretion in how they run particular trials in their courts.

“The judiciary’s role in this has been to pick up vibrations about what is going on. The rationale for many of these offenses is the huge threat that is posed, and the judiciary on the whole have sided with the letter of the law rather than the spirit.”

Despite the growing restrictions, courts across the UK are taking markedly different approaches to protest.

Dr Gail Bradbrook at Declaration of Rebellion, London, 31 October 2018. Credit: Steve Eason

In November 2023, Bradbrook appeared in a London court charged with criminal damage. It was her second time in front of a jury that year; the first trial in July was aborted after Bradbrook defied the judge’s order to stop speaking about her motivations.

At the same time, in another court across London, protestors who were given remarkably similar charges for smashing the windows of HSBC bank’s headquarters in 2021 in protest at its support for the fossil fuel industry were allowed to make the unusual argument of ‘consent’; that they truly believed HSBC’s shareholders would have agreed to their actions if they had known the scale of the climate crisis and the bank’s contribution to it. They were also allowed to speak more broadly about their motivations — even making the argument that what they did was necessary to avoid a greater harm to the planet — although the jury was later told to discount part of their evidence.

And juries are not always following court directions. Over the past four years, around half the people in court for protest have been found not guilty following a trial, even if they have no defense in law. On two occasions juries found climate protestors guilty, but expressed “regret” at having to come to that conclusion. That chimes with a recent poll that found most of the public did not think imprisonment was an appropriate response to disruptive, non-violent protest.

Mansfield said judges were “quite sensible” in past criminal cases, directing juries to disregard certain pieces of evidence but not preventing defendants from talking. “Now what they’re trying to do is to bludgeon it into a situation in which the person won’t have the opportunity to say it at all.”

Again, this is wider than climate protest; in November 2022, a jury acquitted five members of Palestine Action Group of conspiracy to commit criminal damage for throwing red paint over the London headquarters of an Israeli arms firm.

Dr Graeme Hayes, a researcher in social movements at Aston University, said activists are still “trying to find small spaces within the wording of the law, which would enable the jury to give them a not guilty verdict.”

“But they're also trying to emphasize within that morality that the jury is also a moral and conscientious actor, and can take a decision in defiance of the law,” he said.

Over the past couple of years, many cases against climate activists have been funneled through the same central London court, where judge Silas Reid has systematically prevented defendants from mentioning climate change or fuel poverty in their defense. The matter is for “history to judge, not the jury”, Reid told defendants in one such case.

People who defy judge Reid’s order have been charged with contempt of court. Horticultural worker Amy Pritchard and councillor Giovanna Lewis, who glued themselves to a London road in protest at the UK’s energy inefficient housing, spent three and a half weeks in jail in 2023 after mentioning climate change and fuel poverty. They are now appealing their sentences. Care worker David Nixon, who blocked the same road and was imprisoned both for the action and for telling the jury in his trial about his reasons for protesting, compared his sentences to news that violent offenders such as rapists could potentially walk free because of a lack of space in the prison system.

Bradbrook was also threatened with contempt of court for disobeying orders to restrain her evidence. The judge in her case warned he could take an even more extreme decision to move to a judge-only trial —a legal provision designed to avoid jury intimidation in serious organized crime cases that is rarely used.

Cammiss said the inability to contextualize these actions means a key part of the legal process is missing. “To come to a decision without defendants being able to authentically explain what they've done… is highly problematic.”

The approach of the judiciary in protest cases has also elicited a wider public response.

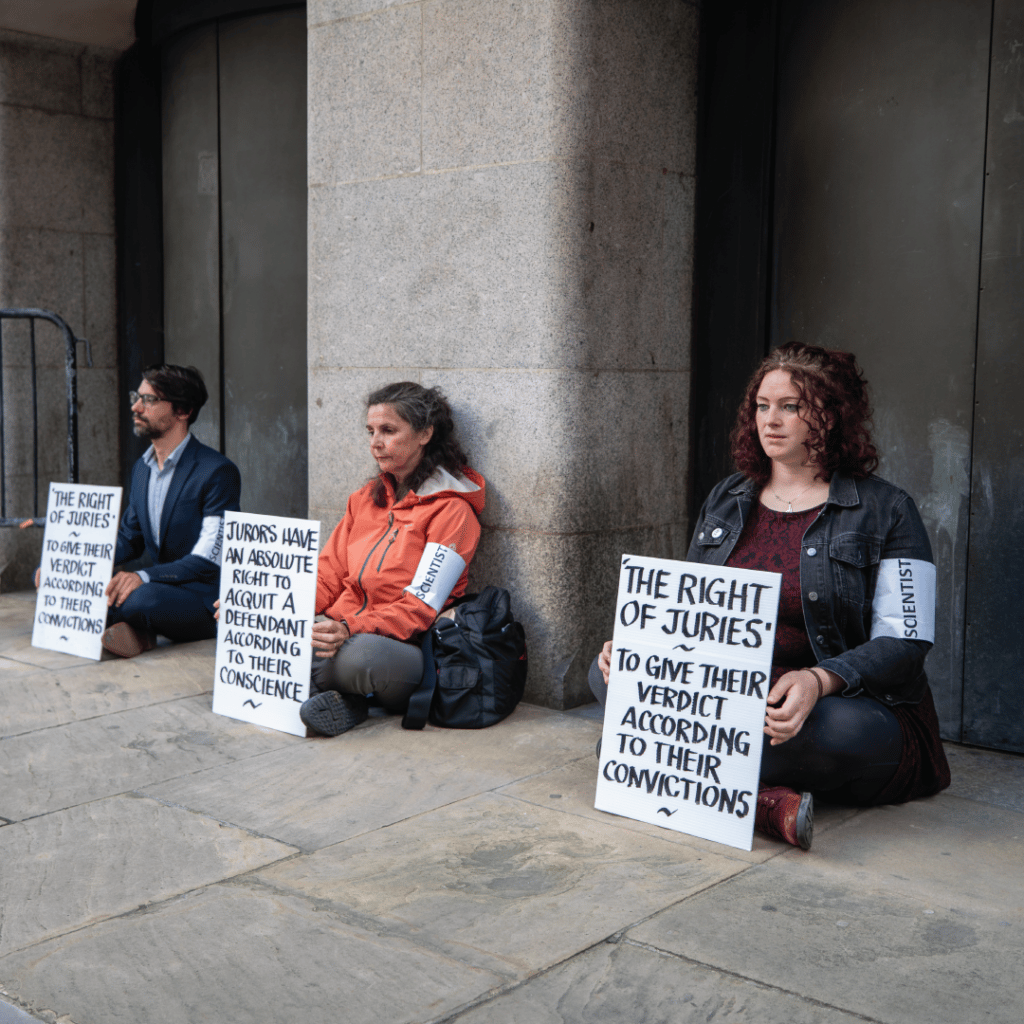

In April, angry about the restrictions being placed on climate activists, 68-year-old Trudi Warner attended a rally to support Insulate Britain protestors on trial at Inner London Crown Court. Outside the court, Warner held a cardboard sign where she’d written: “Jurors: You have an absolute right to acquit a defendant according to your conscience.”

The statement refers to a key legal premise dating back to 1670, when jurors were ordered by a judge to find two Quakers —one of whom went on to found Pennsylvania -—guilty of illegal preaching. The jury, led by a man called Edward Bushel, refused; several jurors were jailed and fined until a court eventually cleared them.

A celebration of this case establishing religious and political freedom, and the resulting principle known as ‘jury nullification’, is engraved in a marble plaque in the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales in London, also known as the Old Bailey.

Activists sit outside a courthouse in London holding replicas of Trudi Warner’s sign in 2023.

But Judge Reid ordered Warner to be arrested when she showed up at court again, after which a High Court judge said she would be charged either with contempt of court, which has a potential jail sentence of up to two years and an unlimited fine, or attempting to pervert the course of justice, which carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.

Warner was charged with contempt in September, followed later on by two young women climate activists - Laura Kaarina Korte and Indigo Rumbelow - who held up similar signs. Others are being investigated.

Since Warner’s arrest, a succession of escalating protests has been held under the banner of Defend Our Juries across the UK. In December, more than 500 people sat silently outside courts all over the country holding placards with the jury nullification slogan while administrative staff, lawyers, judges, jury members and members of the public queued to get through security.

“This goes actually beyond climate,” 84-year-old Renee Slater told me after a protest outside Bristol Crown Court in the south-west of England. “Because it seeks to prevent people from making their case in open court, and therefore it means that it seeks to ignore what is the consensus in society when making a judgement about whether someone has done right or wrong.”

Her daughter and grand-daughter, who also took part in the protest, nodded their agreement. “It's totally undemocratic,” said Slater, who returned to protest again two months later.

Campaigners see what is happening in the UK as part of a wider repression of human rights; the government is currently drafting a law that would enable it to disregard some human rights legislation so it can push through a plan to send asylum seekers to Rwanda.

The government said the bill, which will be introduced in Parliament on Thursday, made clear in UK law Rwanda was a safe country for asylum seekers.

Tensions came to a head in Bradbrook’s second jury trial in November, coincidentally held five years to the day after Extinction Rebellion’s first acts of civil disobedience in London. Outside Isleworth Crown Court in London, silent figures bore placards bearing signs like Warner’s with the jury nullification slogan.

Inside, the prosecutor outlined to a new jury what Bradbrook had done, using CCTV footage, showing tools in clear plastic evidence tubes and calling witnesses to explain how repairing the damaged window had cost £27,660.

When it came to her defense, despite being curtailed repeatedly by the judge, Bradbrook told the jury she felt she had to tell the “whole truth” to be able to have a fair trial and to honor her oath of honesty.

“Our juries are so important because there are times when the application of law is out of alignment with the spirit of justice,” she said.

Representing herself, Bradbrook described to the jury her journey into activism and her duties as a mother to protect the future of her two boys. She said she was vindicated by the government’s decision to scale back the HS2 rail line, which meant a woodland she played in as a child was safe.

“From my perspective, this was not an act of criminality,” Bradbrook told the jury. “This was an act of protection, an act of love. And now I’m in your hands.”

The prosecutor countered: “Even if you admire this defendant, even if you share her beliefs and are just as worried about the environmental damage as she is.. your duty which you just swore to carry out is to reach a verdict according to the evidence, not according to your sympathies.”

The nine protestors who had smashed HSBC’s windows were all acquitted in November 2023. But in the same month, jurors found Bradbrook guilty after just 45 minutes.

On the way out of court, she told me she was at peace with the decision, because she had managed to convey her motivations. She said she hoped the increasing criminalization of climate protesters would draw attention to the “real climate criminals” supporting the production and use of fossil fuels that contribute so much to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

“This is about doing the right thing,” she told me.

Bradbrook’s sentencing hearing took place in December 2023. She was given a 15-month sentence that was then suspended, a 12-month supervision order, and 150 hours of community service. Immediately following the sentencing, Bradbrook released a 75-page dossier of the evidence she had wanted to present to the jury during her trial. “Our so-called justice system is a lottery for climate defenders and not fit for purpose when it comes to tackling the climate and nature crisis,” she said.

The crackdown on protest shows no sign of slowing down. Multiple climate campaigners currently serving jail sentences or awaiting trial in 2024 in the U.K. And in late December the UK’s attorney general asked the Court of Appeal to review whether claims that climate protesters honestly believed organizations affected by their actions would have consented to the damage - as in the HSBC case - can be a defense in court.

However, activists are also continuing to shift their tactics and many have vowed to keep fighting to keep the climate crisis high in the public and political consciousness.