Cover image: ExxonMobil rendering of Liza Unity, its second floating production, storage and offloading (FPSO) vessel in Guyana.

When U.S. President Donald Trump first ordered strikes on Venezuelan ships in September, it was purportedly to intercept drug traffickers. Three months later everyone, including the president himself, acknowledges the role Venezuela’s oil and its fraught relationship with U.S. oil companies over the years plays in the United States’ invasion of the country. But Drilled reporting shows that U.S. oil majors don’t necessarily want back into Venezuela’s declining and decrepit oil fields so much as they are eager to protect their interests in neighboring Guyana, home to one of the world’s most productive oil fields, which Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro has aggressively been trying to claim as his own over the past decade.

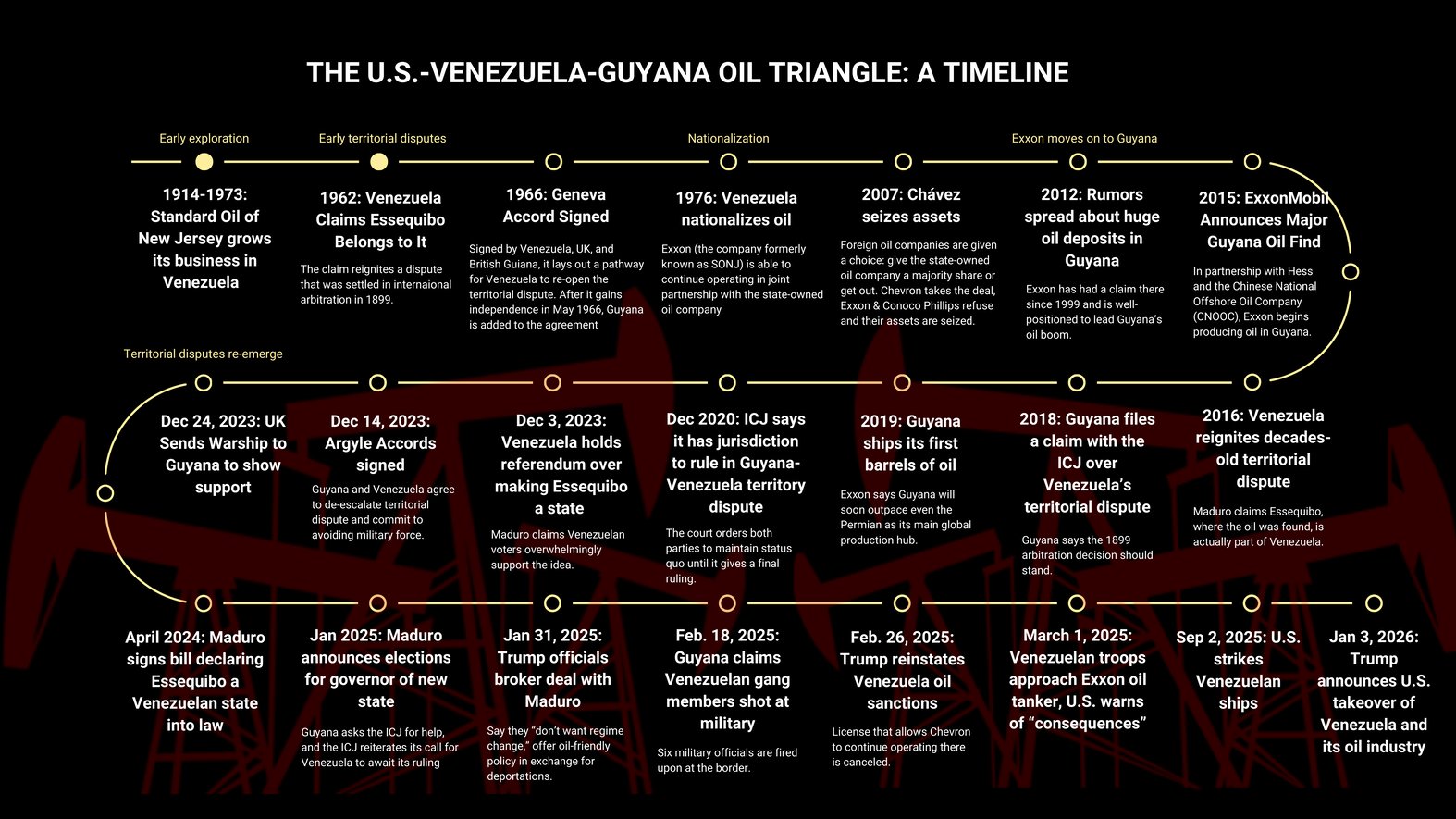

U.S. oil companies’ involvement in Venezuela dates back a little over a century. Spanish colonizers knew there was oil in Venezuela as far back as the 16th century, but the country didn’t begin developing its resources in earnest until the world’s first oil-fueled war, World War I, required it. By the end of that war, Standard Oil of New Jersey (the company known as ExxonMobil today) was active in the country and remained so for decades, joined by Gulf Oil and Chevron (all previous parts of the Standard Oil monopoly). In the 1940s, Standard fought hard against nationalization of the oil industry, launching educational sponsorships to “improve the education of the natives” as one PR executive put it, and spreading the word outside of Venezuela too that American companies were good for Venezuelan democracy. Long-buried documents from Standard’s top PR man at the time, uncovered by Drilled, show that as part of that effort Standard Oil of New Jersey was also deeply involved in combating unionization and labor strikes amongst oil workers in the country, eventually helping to persuade the government to dissolve the oil workers union entirely in 1948.

Newsom’s strategies worked, but not forever. In 1976, Venezuela went ahead with nationalizing its oil industry, but allowed joint ventures with foreign oil companies until President Hugo Chávez decreed in 2007 that all oil projects must cede majority ownership to the state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. or PDVSA. ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips refused and had their assets seized, while Chevron agreed and remained involved in the country’s oil industry.

Exxon returned instead to an offshore exploration license it had held in Guyana since the late 1990s, in partnership with Shell, a stake that had seen little action while the company was able to more cheaply and easily drill in Venezuela. With Chávez more aggressively claiming Venezuela’s oil, Exxon and Shell weren’t the only ones scouting for oil in Guyana in the 2010s. Fredrick Collins, director of the watchdog group Transparency International in Guyana, says the first he and most other Guyanese citizens heard about oil was around 2012.

“We learned that the Surinamese navy had a boat offshore that was entering our waters as well, and it was exploring for oil,” he said.

Alfred Bhutai, a petroleum engineer in Guyana, who also works with Transparency International, said those in the industry have known for decades that there is oil offshore. “I knew in 2012 because I knew some of the researchers who were drilling and finding oil,” he said, adding that the oil companies must have known as well. “The reason we are famous is that Venezuela has denied the US companies their ‘rightful share,’ whatever that may be, and so they set sail to the Stabroek Block [the name of Exxon’s offshore oil field in Guyana), and looked and found oil almost immediately. So I am absolutely sure that they knew that oil was always here and just waited and when Venezuela was going to play bad, they said ‘well okay we have oil elsewhere.”

While it may have known there was oil in those waters all along, ExxonMobil didn’t officially announce its find until 2015, after Shell had left the partnership. Within a few years it was already shipping its first barrel and announcing that Guyana would soon be its most productive oil field in the world, outpacing even its Texas stronghold in the Permian basin. Chevron bought into the project in 2024 via its acquisition of Hess Corporation, a development Exxon fought fiercely but ultimately had to accept when an International Chamber of Commerce arbitration panel ruled in Chevron’s favor in July 2025. The project has faced a variety of lawsuits, protests, and criticisms, but the firm backing of the Guyanese government has enabled it to grow exponentially over the past decade. The one obstacle Exxon had not been able to shake was Maduro, who was growing increasingly obstinate in his claims that Guyana’s oil was actually Venezuela’s.

When Maduro first began yelling about how Essequibo, the Guyanese state that is home to the country’s lucrative oil deposits, is actually Venezuelan territory, few took it seriously. Venezuela had been making this claim off and on since 1962 after all, even occupying and setting up a military base and airfield on a small island in the region since 1966. Maduro’s announcements seemed like just the latest in a long line of brash moves made by a president losing his grip on power and watching his country’s top economic engine—the oil industry—sputter. After decades of drilling, Venezuela’s oil production is on the decline; plus the industry there produces the crudest type of oil, on par with Canadian tar sands oil, which can’t grab the top price that Guyana’s light, sweet crude can earn. And with sanctions on Venezuela’s oil and foreign powers increasingly disinterested in the country’s industry, infrastructure has been poorly maintained.

As Exxon began producing oil in Guyana, Maduro became increasingly aggressive about his claims over the territory, repeatedly violating Guyanese naval and air space. In return, Guyana filed a case at the International Court of Justice. At issue is whether an 1899 international arbitration ruling setting the border where it currently is should stand, or whether the 1966 Geneva Agreement, signed between Venezuela, the U.K., and British Guiana (eventually Guyana once it won independence) effectively re-opened the border dispute. The ICJ issued an interim ruling in 2020 asserting its jurisdiction over the dispute and barring any changes in governance of the region pending its final ruling, which has not been delivered to date. Nonetheless, in 2023, Maduro held a referendum, asking Venezuelans to vote on whether to make Essequibo a Venezuelan state. Maduro’s government, which has repeatedly been accused of rigging elections, claimed the referendum passed with overwhelming support and that Essequibo—which is not only home to Guyana’s booming oil industry, but also represents two-thirds of the country’s territory—should be a Venezuelan state. At the same time, Venezuela began expanding its military operations in the region. With tensions escalating, Maduro and Guyana’s president Irfaan Ali met in the Caribbean to discuss the territorial dispute, and signed the Argyle Accords, agreeing to de-escalate the situation, avoid military action, and maintain the status quo while both countries await the ICJ’s decision.

Nonetheless, tensions increased, with Guyana asking for the U.K. military’s support in a show of strength to Venezuela in late 2023 and Maduro responding in kind with military defense exercises and the deployment of troops and equipment to the border between the two countries. In April 2024, Maduro signed the resolution declaring Essequibo a Venezuelan state into law, which Guyanese officials declared a breach of international law. Maduro seems to have put the territorial dispute on the back burner for a few months to focus on getting re-elected, an effort that, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, required redirecting military resources toward rigging the election and suppressing protest, but was back at it in early 2025, announcing in January his intention to hold elections for a governor of the new Venezuelan state of “Guyana Esequiba” later in the year. Guyana once again turned to the ICJ for help.

“The people of Guyana’s Essequibo region are Guyanese nationals who live in Guyana’s sovereign territory,” Guyana’s foreign ministry wrote in a statement about the dispute. “It would be a flagrant violation of the most fundamental principles of international law, enshrined in the U.N. Charter, for Venezuela to attempt to conduct an election in Guyanese territory involving the participation of Guyanese nationals.”

In February 2025, Guyanese officials claimed that six Guyanese soldiers were shot and injured at the border by what they described as “Venezuelan gang members.” One week later, the Trump administration reversed its position on Venezuela entirely, from explicitly stating it “did not want regime change in Venezuela,” and brokering a deal in late January 2025 that had Venezuela paying for the deportation of its citizens from the U.S. in exchange for friendly policies, to Trump’s announcement in February that he was canceling the license that had allowed Chevron to continue being a part of joint ventures in the country despite U.S. sanctions on Venezeula.

A few days later, Venezuela responded by sending a war ship directly to Exxon’s floating oil production vessel and demanding information from its crew. Guyana responded by deploying its airforce and enlisting the help of its allies, including the U.S.

The Organization of American States, the regional body uniting all 35 countries of the Americas, issued a statement condemning the move as a threat to ExxonMobil’s operations in the region and “a clear violation of international law,” that undermines regional stability and threatens peaceful coexistence between nations in the region.

“The OAS reiterates its steadfast support for Guyana’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. The Venezuelan regime must immediately cease all aggressive manoeuvres that could escalate tensions in the region,” the statement read. The U.S. State Department also voiced its support, stating that further provocation “will result in consequences for the Maduro regime.”

Meanwhile, several oil majors—including Chevron, Total Energies, Shell, and Petronas—have now also set up shop in neighboring Suriname, where they plan to drill directly into the same reservoir Exxon and Chevron are tapping on the Guyanese side of the maritime border between the two countries. There have historically been disputes over this border as well, but so far the presidents of Suriname and Guyana are encouraging “energy cooperation” and cross-border joint ventures amongst the various private companies interested in their respective resources.

As of January 3, 2026 Maduro and his wife had been arraigned in New York not on charges related to election rigging or territorial disputes or threats to ExxonMobil, but on drug charges. At a press conference, Trump described Maduro’s crime against the U.S. as “narco-terrorism” before going on to describe how the U.S. would take over Venezuela’s oil industry.