Fossil fuel companies profiteering from the Venezuelan oil seized by the United States risk falling foul of international law, and could end up facing litigation in various jurisdictions, a UN expert has warned.

The Trump administration has captured seven tankers of Venezuelan oil since early December, as part of a series of unlawful actions including a unilateral military operation on 3 January to abduct the sitting president, Nicholas Maduro, and his wife, Cilia Flores—a move widely condemned as a direct violation of the UN charter and other customary international laws.

Trump has said that the U.S. intends to control Venezuela’s oil sales and revenues indefinitely, and has met with an array of company executives that he wants to do oil business with.

But corporations are obliged under international law to act with due diligence to avoid and/or remedy rights violations, and not engage in commercial activities linked to unlawful actions, according to Fernanda Hopenhaym, member of the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights.

You can also listen to the interview with Fernanda Hopenhaym on today’s podcast episode, here or wherever you get your podcasts.

“All of the [U.S.] military intervention has been done unilaterally and outside of international rules, so whichever angle we look at it from, we end up concluding that this is a blunt violation of the UN charter.

“And now the extraction of oil and supposedly the sale of oil is really something that it's being done in a total void of a legal framework. So that is something that companies need to consider because they can be complicit in these illegal actions,” said Hopenhaym, in an interview with Drilled.

Scores of companies—from European based commodity traders and multinational oil majors to U.S. refineries and processors—have been linked to the extraction, trade, and production of the Venezuelan oil that President Trump has commandeered, despite major questions about the legality of Trump’s unilateral sanctions and military operations against the South American petrostate.

According to the Financial Times, the first U.S. oil sale went to a Dutch energy and commodity trading company Vitol, whose senior oil trader donated $6m to Trump’s reelection campaign and met with the president to secure the $250m crude deal. Another global trading house, Trafigura, the second largest oil trader, has also secured a license from the Trump administration and reportedly bought $250m of Venezuelan crude. The Singapore-based trading house and its subsidiaries spent almost three quarters of a million dollars on lobbying Washington D.C. in 2024/25 according to the political finance watchdog Open Secrets.

Vitol and Trafigura will sell the Venezuelan oil they buy from the U.S. on to their customers, exposing more companies to potential legal action. Both trading companies have been implicated in bribery scandals by the U.S. Justice Department.

“Many of these companies, particularly European companies, could be taken to court by different organizations and institutions and/or plaintiffs from Venezuela or outside Venezuela because this exploitation of oil is being done goes against everything the international courts are saying,” said Hopenhaym.

“First of all, I would warn don't go to Venezuela now, because the illegal actions have put the country in a position where there is a void, a legal void. Second, you don't want to be causing or connected to human rights violations on the ground in Venezuela when you try to extract oil, so you need to conduct due diligence.”

Thirdly, warns Hopenhaym, states could also be held responsible for corporate wrongdoing because many have laws mandating transparency, due diligence, and environmental protection—which are all at play in Venezuela. “Companies really need to be careful here. It’s not just a business opportunity and it's not about the welfare of Venezuelans. The situation of the Venezuelans is as terrible as it was before they took Maduro to the U.S. and nobody cares.”

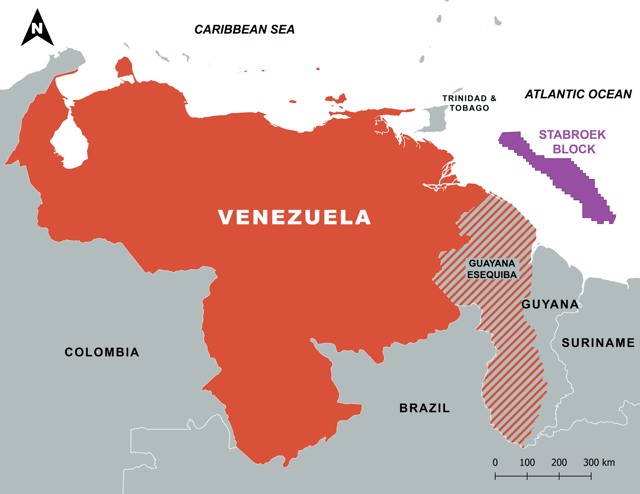

Venezuela has the largest proven crude oil reserve in the world, with an estimated 303bn barrels, according to research group the Energy Institute, almost as much oil as the U.S., Canada and Russia combined.

Aging infrastructure, corruption, poor governance, international sanctions and falling global demand, particularly for the sort of heavy crude produced in Venezuela, has seen the country’s oil extraction fall from a peak of more than 3m barrels per day (bpd) in the late 1990s after nationalization, to around 1m bpd (including refined products and petrochemicals) currently, accounting for 0.9% of the global supply.

Trump’s desire to ramp up oil extraction to the country’s previous peak of one billion barrels per year would be a flagrant violation of international law, according to the 2025 International Court of Justice climate ruling.

A host of sanctions have been imposed on government entities and individuals in Venezuela since 2014, the year after Maduro took over from Hugo Chavez, with the U.S. currently sanctioning 209 Venezuelans, according to an Atlantic Council tracker.

Between 2017 and 2019, the Trump administration levied additional economic sanctions on individuals or companies in the petroleum, gold, mining, and financial industries. Some of these were lifted—and then reimposed—by the Biden administration, yet fossil fuel companies such as Chevron were given waivers or individual licenses to continue operating, and oil extraction increased.

In December 2025, the Trump administration announced a “blockade of all sanctioned oil tankers going into, and out of, Venezuela,” and deployed a large military force to the Caribbean sea near Venezuela. The blockade came a month after the U.S. designated multiple government officials, including President Maduro, as part of an alleged “foreign terrorist organization” known as Cartel de los Soles. (Cartel de los Soles is an umbrella term used by the media to describe corrupt Venezuelan officials with alleged links to drug trafficking, it does not exist as a group).

Shortly after U.S. armed forces seized the first oil tanker, Skipper, off the coast of Venezuela on 10 December, the Trump administration imposed new sanctions targeting Maduro's family and oil shipments to disrupt what the U.S. Treasury described as a “persistent web of corruption, narco trafficking and sanctions evasions that continues to sustain Maduro's 'illegitimate' government". This included six companies and its vessels the U.S. alleged were part of a shadow fleet “engaged in deceptive and unsafe shipping practices.”

Trump has repeatedly justified the maritime blockade in the Caribbean by claiming the U.S. is simply seizing oil and/or tankers which are "sanctioned.”

But UN experts have condemned the unilateral imposition of sanctions and force by the U.S. against Venezuela as fundamentally unlawful.

“There is no right to enforce unilateral sanctions through an armed blockade… There are serious concerns that the sanctions are unlawful, disproportionate and punitive under international law, and that they have seriously undermined the human rights of the Venezuelan people and the Sustainable Development Goals,” a group of experts said in December.

A dozen Democratic lawmakers have also warned oil and oil field service companies linked to the Venezuelan oil grab of the legal and financial risks posed by any transaction or investment that relies on the Trump Administration’s asserted authority to control the country’s crude assets.

Last week, the Trump administration via the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control authorized U.S. companies to buy, sell, transport, store and refine Venezuelan crude oil. It did not lift existing U.S. sanctions on production, and specifically excludes firms and individuals from so-called enemies China, Iran, North Korea, Cuba and Russia.

As the U.S. ratcheted up pressure on Mexico to stop supplying Cuba with oil, Greg Grandin, Yale history professor and author of America, América: A New History of the New World, described the U.S. capture and control over Venezuelan oil as “straight-out criminal activity… because it’s based on no international law.”

“When the United States says that Venezuela has sanctioned oil, that’s just the United States asserting it. It’s not — it’s not ratified by any international body,” Grandin told DemocracyNow.

It’s not just the seized tankers.

Trump has claimed that Venezuela has “stolen” U.S. property, namely crude oil, and must return it to American companies unable to do business in the country after the petroleum industry was nationalized.

Much has been made of the agreement between Trump and Venezuela's interim president Delcy Rodriguez, which was made amid threats of further military aggression, allowing the US to control the oil industry and revenues. In addition, sweeping pro-foreign business reforms to Venezuela’s main oil law approved in late January, which seek to encourage international companies to invest in infrastructure and increase oil and gas production.

Yet even contracts that are legally sound in Venezuela and greenlight by the U.S. government may not suffice as a legal defense—especially if international companies fail to exercise due diligence in the protection of human rights including Indigenous peoples’ rights or fail to follow international environmental and climate legal rulings and other relevant jurisprudence, according to Hopenhaym.

“Even if a company can argue that it has a legal contract with the current Venezuelan government, if you're an international actor and [given] all the breaches of international law that have happened, you can be complicit nevertheless. It's not just about the legality of the contract according to Venezuelan law, it's broader.”

The 2011 UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) are key here, according to Hopenhaym, an expert in corporate accountability in Latin America.

The UNGPs are the international gold standard on state obligations, corporate responsibility and access to remedy when violations happen in the course of business operations. While not mandatory, this soft law lays out clear rules and minimum standards for international companies based in international law, regardless of where they are doing business.

In addition, the EU and many individual European states including the Netherlands, France and Spain—which all have companies linked to Trump’s Venezuelan oil boom—have now adopted frameworks with higher, sometimes mandatory standards.

“[The companies] are probably navigating a gray area where the world hasn't been able to react to this kind of shocking storm of illegality, and they are just saying we're gonna profit from this gray area… I foresee a lot of cases coming to courts in the coming years because the problem is when you violate the law that it only takes you so far.”