Drilled • Season 12 Episode 1

Welcome to SLAPP’d | Episode 1: How did we get here?

About This Episode

Transcript

Transcript

[archival video - protestors chanting “Water is life!”]

A small crowd of people gathered on the side of North Dakota Highway 1806, just north of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. A line of Highway Patrol officers were standing between them and a construction site. Cody Hall, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, was in the crowd.

Cody: Those bulldozers were up and, and running. And we saw them moving the earth.

If those bulldozers were allowed to continue, a massive drill would soon bore a hole underneath the Missouri River to make way for the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Cody: The tension was so thick, that, that something was going to happen physically. And I remember thinking, I was like, ‘Oh gosh, people are really at their boiling point.’

I'm sitting there, you know, kind of pacing back and forth.

I happened to look over to my right, and I saw the women, and they were singing their death song. And in our culture, when you sing your death song, that means you are obviously not afraid to die.

Cody: Um, and then all of a sudden a group of women went and jumped the fence, the barbed wire fence.

Nobody had planned this. The fence marked the edge of the area where police were allowing protest. Beyond it lay the construction site and open grasslands.

I was like, ‘Hey, hey, you know, stop.’ You know, I was like, just, ‘We don't know what's going to happen and they might shoot you, right?’

And I remember one of the ladies said she didn't care. She said that she doesn't fear a bullet. She doesn't fear death.

And when I saw her take off, and I, I remember looking back at friends, and I was just like, and people were like, whoa, you know, ‘Stop, stop. Hey, come back, come back.’

And then I said, ‘Forget this.’ I said, ‘Every, every man available, jump the fence, and let's stand behind them, let's go help the, you know, these women defend, defend our lives.’

They ran onto the construction site, halting the work.

Archival Clip: We do this to stop the desecration of Unci Maka. We do this for the next seven generations. We do this for the unborn children that are coming to this world. We're protecting the water. Our water is life!

Cody: The momentum was there, the people's energy. It was something I had never felt before in a big group.

[protest archival] We stand for our land and our water. We'll not let it get desecrated. They're not allowed to make no pipelines on this land!

Cody: We, we had that feeling that we were going to defeat this, this energy company.

Alleen: You probably already know. The Dakota Access Pipeline was eventually built. But before it was, tens of thousands of people arrived on the prairie just outside the Standing Rock Reservation and attempted to stop it. Standing Rock became the largest Indigenous uprising in the U.S. in the last half century, and it was happening in opposition to an oil pipeline company.

Maybe that’s why the company behind the pipeline, Energy Transfer, did what it did next. In 2017, After the oil was flowing. After police forced the huge encampments of pipeline opponents and water protectors to go home. Energy Transfer filed a lawsuit. A really big one.

The company claimed that the whole Standing Rock movement, the massive effort to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016, was actually a conspiracy driven by Greenpeace – the save the whales guys. According to the pipeline company, it wasn’t the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe or other Indigenous people who led the movement, despite what numerous media reports, eyewitnesses, and public officials will tell you. It was a giant environmental nonprofit conspiring to take down the fossil fuel industry.

I’m an environmental reporter focused on the criminalization of environmental defenders. I’ve been covering Standing Rock since the early days of the movement. And Energy Transfer’s allegations against Greenpeace defied both what I’d seen with my own eyes at the protests, and what I had learned over years of reporting on the Standing Rock movement.

The story the lawsuit told was so different from what I’d heard from Cody and others. Source after source had told me Indigenous people and nations made their own decisions to stand up against a company that threatened their water and their rights to land.

Regardless of how ridiculous this lawsuit seemed, in 2025 it made it to trial.

And in March, I found myself sitting in a courtroom in Mandan, North Dakota, listening to a court clerk reveal the verdict. After a three and a half week trial, the jury decided overwhelmingly in favor of the pipeline company’s story. The total damages: over $666 million. A number that threatened to bankrupt Greenpeace in the U.S.

I’d spent nearly a decade reporting on what had happened with the Dakota Access Pipeline and the Standing Rock movement. I sat through the lawsuit’s nearly month-long trial, in that same room with those nine jurors. The evidence I had heard was thin. And yet the jury delivered almost precisely what Energy Transfer’s lawyers asked for.

How the hell did this happen?

And if an oil company could push its version of events so successfully here, then what did that mean beyond this courthouse?

This season of Drilled we bring you SLAPP’d. The story of an Indigenous nation fighting for its water, an environmental nonprofit facing extinction, and an energy giant using the courts to punish protestors. I'm Alleen Brown.

Alleen: To understand what happened in the Energy Transfer v. Greenpeace case, we have to start at the beginning, with Cody Hall, who you heard from earlier. He was actually at the center of Energy Transfer's lawsuit — until he wasn't.

Cody: I’m from the Cheyenne River Indian reservation in South Dakota

Alleen: The Cheyenne River reservation where Cody lived is immediately south of Standing Rock. Both reservations are home to the Oceti Sakowin people, also known as the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota. The people who live there aren't just neighbors; they're relatives.

Cody helped start the Native Lives Matter movement there. So it was natural that he would be asked to join the fight to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Cody: I was approached by some elder groups, uh, or an elder group in Eagle Butte, there on my home reservation, that said, ‘There are people gathering, uh, in Standing Rock. Um, can you go up, you know, and just get an assessment of what's going on, Cody?’

Alleen: Cody arrived at a protest encampment on the Standing Rock reservation in early August of 2016.

Cody: I went up there with just a backpack of, I think, three days of clothes. You know, um, and then ended up being there months.

Alleen: Energy Transfer had originally considered putting the Dakota Access Pipeline upstream of the city of Bismarck, which is mostly white. But the federal Army Corps of Engineers rejected that route in part because it could have harmed the city’s drinking water supply. The new, approved route crossed the river just north of the Standing Rock reservation and its drinking water intake. To Cody and others this was a case of environmental racism.

People had begun to travel from all around the country to defend the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s drinking water, sacred sites, and land rights. They called themselves water protectors. Facebook Live had launched that spring, and many pipeline opponents were using it.

Archival Video Clip: You can see there are people walking around all around camp in little pockets, and this is the main camp, there are still other camps like Sacred Stone, which is up there, and Eagles Nest and the new Cheyenne River Camp, which is down that way…

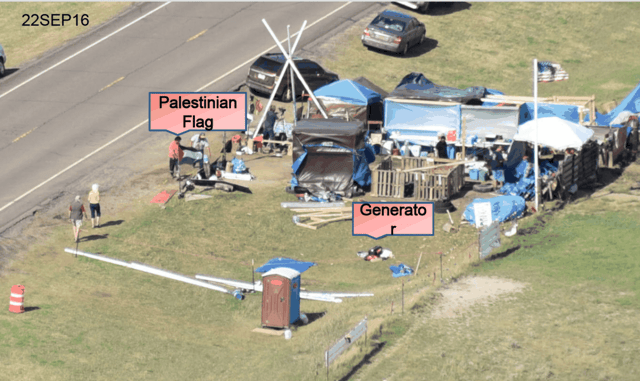

Alleen: in late summer people began to set up additional tents and teepees on federal land near the pipeline crossing. This new encampment, called the Oceti Sakowin camp, was on land officially possessed by the Army Corps of Engineers — but that people from Standing Rock still considered theirs.

Cody: It, it, it felt home. It took your spirit back, uh, to a, a much loving time period, uh, of our people. And I thought, you know what? Yeah, there's nothing wrong with taking back land, right?

Alleen : The camp was established on unceded territory, an official designation that means that Oceti Sakowin people never agreed to give it up. The area where Energy Transfer was building was also unceded territory.

For the water protectors the pipeline fight was a matter of Indigenous sovereignty. The Standing Rock Sioux tribe is a nation. And they argued the Army Corps shouldn't allow the pipeline to pass under the river or over culturally significant areas, without substantial government to government consultation.

Soon after Cody arrived, he was approached by Deb White Plume, a member of the Ogalala Sioux Tribe.

Cody: I knew of Deb and, um, knew what she was doing, um, long before any pipeline, uh, came about, uh, in our territories.

Alleen: Deb died in 2021. But she lived a life dedicated to defending Lakota people. In the 1970s she joined the American Indian Movement. And Deb led a resistance group that protested against the Keystone XL pipeline, which was set to be built through her nation's territory in South Dakota. Now she was bringing a version of that group to Standing Rock. They were called Red Warrior Camp.

Cody: I remember she asked me, she said, ‘Cody, you speak so eloquent, right?’ And she said, ‘I would like for you to be a spokesperson for my resistance camp.’

SAhe talked about how people chain themselves, uh, to block the, proceedings of whatever it may be, you know, and I thought, okay, um, especially it being non, non violent. I say, wow, that's kind of what I've been speaking about.

Alleen: After giving it a couple days thought, Cody agreed to be spokesperson for Red Warrior Camp.

Around the campfire, with the other members of the group, he laid out some ground rules.

Cody: I said, ‘I don't want to know what you're doing, what you're planning. If you tell me what you’re doing, and I get picked up, let's say, you know, um, and they question me, then you start breaking down the chain of resistance. So don't tell me. I don't want to know.’

Alleen: He also told them he was only interested in supporting nonviolent actions.

Cody Archival Video Clip: Hi my name is Cody Hall, spokesperson for Red Warrior Camp. Today...

Alleen: Cody's job was to film short videos and livestreams that he posted to Red Warrior Camp's Facebook page. Some were filmed from within construction sites where people were locked down to machinery. He wasn’t planning the actions, but he became the public face of Red Warrior.

Cody Archival Video Clip: As you can see behind me, one of our warriors put himself on the machinery to stop today’s construction. They are very near…

Alleen: The fight against the pipeline seemed to be taking off, but really it was only getting started. Energy Transfer didn't have an easement from the Army Corps yet, which would allow them to drill under the river. But there was nothing stopping the pipeline company from building on private land. Standing Rock had filed a lawsuit in July to stop that construction. But while they waited for a judge to rule, Energy Transfer kept on bulldozing.

Amy Goodman, Democracy Now!: In North Dakota, security guards working for the Dakota Access Pipeline company attacked Native Americans with dogs and pepper spray as they resisted the 3.8 billion dollar pipeline’s construction. Amy Goodman, Democracy Now!: Criminals, you guys are criminals. Go get your money somewhere else. Yeah you.

Amy Goodman, Democracy Now!: Protesters advanced as far as a small wooden bridge. Security unleashes one of the dogs, which attacks two of the Native Americans’ horses. Security has some kind of gas — people are being pepper sprayed.

Water Protector, Democracy Now!: We’re not leaving, we’re not leaving

Alleen: On Labor Day weekend, water protectors spotted bulldozers working right where the Standing Rock Sioux tribe had just identified sacred sites, only the day before. Several people rushed onto the construction site to attempt to stop them.

Democracy Now! captured security dogs attacking the pipeline opponents. And the movement went viral.

Cody: It opened the floodgates, um, and when those gates were opened, craziness ensued.

Alleen: People from around the world poured into the pipeline resistance camps, from members of Indigenous nations who saw this fight as their own, to everyday people moved by water protectors' social media feeds, to longtime environmental activists who felt a responsibility to show solidarity. Churches, community groups, and individuals donated supplies to keep the camps afloat. A school opened for families with children. Several kitchens served meals throughout the day. By now, nonprofits had joined the fight, too, like 350.org, Indigenous Environmental Network, Honor the Earth, Bold Alliance, and yes, Greenpeace.

It was a powerful moment. But when protests get the sort of international media attention Standing Rock got, it doesn't just attract the people who are committed to the cause.

Also arriving were crystal chasers, cult members, grifters, and even professional infiltrators looking to get information about the resistance to share with the pipeline company or police. Things started to spin beyond anyone’s control. Tens of thousands of people traveled in and out of the prairie encampments with their egos and their agendas, which sometimes aligned with those of the tribe, and sometimes sat directly in opposition.

Millions of dollars also began pouring into hundreds of Go-Fund-Me pages. Sometimes the projects people promised were built, and sometimes they weren't.

At the same time, the governor of North Dakota called in the National Guard, which joined law enforcement officers from around the [00:24:00] country, to try and disperse the protests. They brought military-grade armored vehicles, surveillance drones, and surface-to-air missiles.

And word began to spread that the pipeline company had hired a mercenary security firm fresh from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. As far as the water protectors were concerned, the line between police and private security was a blur.

Overhead, helicopters and little Cessna planes flown by police and private security buzzed at all hours.

In between the steady beat of protests, a feeling had seeped in that Cody was being targeted.

Then, as he was driving to drop someone off at the airport, a law enforcement officer waved Cody to the side of the road. He was under arrest for trespassing.

Cody: so when I turn around and the patrolman is, is handcuffing me, first thing I did was count how many. They were 18. I saw that physically they were, you know, like I said, head to toe and all this SWAT gear. They had helmets on, goggles, um, face masks, um, body armor. And then they had their AR-15s pointed at me.

They put me in the backseat and I met with cheers, right? Um, as I'm getting in and those law enforcement, those guys dressed in SWAT gear were, you know, were yelling out, ‘We got you, you motherfucker over and over again.’ And I'm like, ‘What the hell?’ I said, ‘Whoa, guys, I was like, I was like, I said, man, you guys take it, take it too far.’

Alleen: At the station, Cody says he was stripped naked and searched. Two FBI agents attempted to interview him, but he refused to tell them anything. At night, cold air was blasted into his cell, and every couple hours, an officer would enter and tower over him.

Ultimately he was bailed out. As he left, a young officer told him the FBI had been watching him on cameras the whole time.

I asked Jacob O'Connell, the FBI’s supervisor at the time for the western half of North Dakota , if he remembered this. He said he didn't and that it wasn't something the FBI would have done. The Morton County Sheriff’s office declined an interview request and didn’t respond to a list of questions.

When Cody returned to camp, he says the feeling of being watched was more intense than ever.

Cody: But also felt like, um, that I might be being used as a scapegoat.

Alleen: Soon after his release, Cody attended a rally at the Morton County courthouse to support other water protectors who had been arrested. He noticed something that seemed off.

Cody: This individual kept, um, tailing me, and I thought, well, let me, just let me walk around, right? And, uh, see if this person is still going to follow me. And sure enough, this, this individual was. So I thought, ah, crap.

Cody: A group of people came up and said, ‘Hey, Cody, um, you got to ride back to camp.’ And I said, ‘Uh, no, I don't.’

Alleen: When Cody realized who the driver was, he hesitated. It was that same guy who seemed to be following him around. But his friends reassured him that the guy was vetted and had been staying at the camp.

Cody: I just remember there's like 13 of us that packed into this van.

When he asked me to sit with him up, up front, I thought, ‘Oh, shit. Okay, one, I need a ride back to camp. Um, I'm just going to use this ride. But then two, my alert's already going off.’ Cause I was like, ‘Why is he asking me to sit up front? Hmm.’

So we get back to camp. I open the door up, and he said, ‘Hey, hold on one second, Cody. Can I have a word with you?’ And I thought, ‘Oh shit.’ And I got back inside. Didn't close the door all the way. I remember I still had it latched open, right? And I was looking at him, and I said, ‘What do you want?’ And then he started to reach on his left pocket of his jacket, inside.

I’m like, ‘I don't know what you're reaching for, but,’ I said, ‘this is the wrong idea to do at this camp, but.’ I said, ‘I'll fuck you up. I literally will fuck you up before anything happens.’ And then he kind of, he showed an envelope, didn't open it, he just pulled this envelope out. And he said, ‘I got money for you.’ And I said, ‘What, what do you mean?’ He said, ‘We at Greenpeace piled up all this money, because we watched one of your videos looking for support. So we gathered up supplies and we have monetary donations here. So I want to give it to you.’

Alleen: I asked Greenpeace about this. They said they are so careful about money that this isn’t something they would have done. Cody said the man offered him over $200,000.

Cody: And I said, ‘No, no, I don't,’ I said, ‘I'm not, I'm not taking anything, man. Okay.’ And, I remember my instinct said, ‘Get the hell out of there, get out of this guy's vehicle.’

I walked away, walking backwards, looking at this guy. He drove away, and I just remember telling security, ‘Hey, watch that individual. It's some sketchy.’

Alleen: Cody didn't mention the details of what happened to anyone. It was another bizarre incident, amongst the mountain of them piling up every passing week. But the envelope man incident would come to take on greater meaning later.

By the end of October 2016, Cody was clashing with members of Red Warrior Camp.

Cody: People were being shot with rubber bullets, so-called nonviolent in the law enforcement area, right, um, in their point of view.

But so Red Warrior people were like eff this. And I, and it started to turn the, um, the inner core of them, um, just, you know, just hated everybody, including myself, more myself. Um, they didn't like the narrative that I was speaking of, um, of nonviolent and, um, you know, just, just take it, right? Just take it, take it, take it.

So they were frustrated, um, and then took their frustration out on me.

I just said, ‘I'm done with you guys. That's the way you want, and that's what you want?’ I said, ‘Then I'm done with y'all.’ And they were like, ‘Well, we're done with you.’ And I was like, ‘All right, mutual agreement. I'm not your spokesperson anymore. Best of luck to you.’

Alleen : Cody wasn't the only one who had problems with Red Warrior Camp. They’d become controversial at Standing Rock for using aggressive tactics. On the day after Halloween, the Standing Rock tribal council voted Red Warrior Camp out.

Cody had already made his decision. He left, driving south until he got back home to the Cheyenne River reservation.

...

Alleen: I actually arrived at Standing Rock a couple weeks after Cody left. I was there on assignment for the Intercept, an investigative news outlet. Part of the reason I was interested in these protests was because they were coming at a time when the fossil fuel industry was especially vulnerable. People were really beginning to recognize the impacts of the climate crisis, and fossil fuel companies’ role in it. These corporations weren’t just facing a single blockade of activists at Standing Rock. As the climate crisis got worse, they were facing the possibility of escalating protests.

The road into camp was lined by flags from all the Indigenous nations that had visited. Seemingly hundreds of teepees, tents, yurts, and trailers were set up in the middle of the prairie. The sky felt bigger here and closer to the ground. A lot of what was happening at camp was the daily work of surviving in the November cold. Respected elders from Standing Rock sat on folding chairs under blankets near a sacred fire that was always burning. Lakota and Dakota people I talked to told me that what was happening here was spiritual for them. When I asked for interviews, some people jokingly asked me if I worked for the pipeline company.

Water protectors knew that there were spies among them.

There was a feeling in the air that something rare and important was happening, but that it could go off the rails at any moment.

I saw the helicopters and little planes flying overhead all the time. I followed a caravan of protesters to a spot where people were blocking construction. The planes shadowed us as we drove. At night, a row of lights beamed eerily from up on a hill, along where the pipeline was being built. And next to the camp, police and private security had erected concrete barriers and barbed wire across Highway 1806. Two burnt-out trucks served as an additional boundary.

Right after I left, water protectors attempted to tow away the burnt out trucks, and, during the protests that followed, police used hoses to spray icy water at people, in sub-freezing weather. Medics on the ground told me they treated 168 people for hypothermia.

Here’s from a Facebook Live video filmed as the hoses were fired.

As winter set in, anxiety over surveillance and infiltration was causing conflict, as people whispered about who might be working as a spy for the pipeline company or the government. For Cody, weird stuff related to money had continued to happen. Back on Cheyenne River, he says a guy he’d never met showed up in his hometown and attempted to hand him a duffel bag of cash. Cody sent him away. He suspected these incidents were attempts to set him up.

Meanwhile, local journalists had begun to raise questions about where the millions of dollars in GoFundMe donations actually ended up. Even Cody had run an online fundraiser for Red Warrior Camp that raised over $100,000 from over 2000 individual donations He said he donated what was left to an organization that supported Indigenous sovereignty.

In January 2017, just after Donald Trump's first presidential inauguration, the Army Corps gave the green light for Energy Transfer to drill. That February, police kicked out the remaining water protectors camped at Standing Rock. And a giant drill bored a hole underneath the wide Missouri River, before the pipeline was pushed through.

Cody began to move on. He moved to Kansas City to join a woman he’d met at Standing Rock. She had kids, and he found himself stepping into a role as a father. He started driving for a limo service.

But his sense of normalcy wouldn't last. In August 2018, Cody Hall got a strange message, that he didn't expect.

Cody: I remember getting ready for work, and a college friend of mine that was working legal fund or legal thing up in North Dakota, um, said, messaged me on Facebook and said, ‘Hey, Cody, uh, have you heard the latest news about you?’ And I thought, ‘Oh shit, here we go. What is it?’ And so I said, ‘No, I didn't.’ I said, ‘Well, um, what's going on?’

And so she said, she sent me a link. And I opened the link, and there it was. It was all the, the, the documents from court.

I mean, when I read it and I was like, ‘Holy crap.’ And she said, ‘Hey, uh, if I was you, I would, you know, reach out and get a lawyer because this is pretty serious.’

Alleen: Energy Transfer, the company that built the pipeline, was suing Cody Hall in federal court for hundreds of millions of dollars in damages. The charges were defamation, trespassing, tortious interference with business, and racketeering activities that included drug dealing, wire fraud, and violations of the patriot act — in other words, terrorism.

Energy Transfer filed the claims using the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, the RICO Act, a law originally written to go after the mafia.

Every RICO case first has to define what they call "the enterprise," the network of people working together to commit crimes. In this one, Energy Transfer claimed that network was Cody, not-for-profits and a group of rogue eco-terrorists. And that it was not led by Indigenous people, but by the environmental nonprofit Greenpeace. In the pipeline company’s telling, Red Warrior Camp was a front group for Greenpeace. They were the "primary perpetrators of disorder and violence." And Cody was their leader.

Cody: I never, I never created Red Warrior. Red Warrior. was a resistance camp founded by Deb White Plume.

Alleen: Cody says he didn’t lead Red Warrior Camp either; he was simply their spokesperson. And he says he never took money from Greenpeace.

Cody waited for something to happen. When you get sued, the person suing you, the plaintiff, is supposed to make sure you get notice of the suit. But Cody never got served. Then, six months later, the suit was dismissed. The judge wrote, “This is far short of what is needed to establish a RICO enterprise.”

Cody: I thought, ‘Hey, we actually got somebody that's working in the legal system that says this is ridiculous. Great.’ I was like, ‘Ah, relief.’ And then here later that day, you know, my friend messaged and said, ‘Well, that wasn't lived too long.’

They filed in state court. They just used lesser words and made more false claims. And I thought, ‘Oh shit, we're still at it, so, damn it.’

Alleen: In Energy Transfer’s new version of the story of Standing Rock, filed in a North Dakota state court, Cody, Greenpeace, Red Warrior Society, and another Indigenous pipeline opponent named Krystal Two Bulls conspired to launch a coordinated campaign to stop the pipeline in July of 2016, before Cody even arrived. For the legal wonks out there – the lawsuit actually accused three separate Greenpeace organizations of being involved. They include U.S. based Greenpeace Inc. and Greenpeace Fund and Amsterdam-based Greenpeace International. But even though Cody had had that strange encounter with the man who said he worked for Greenpeace, Cody didn't believe that the nonprofit was running the show.

Cody: No, Greenpeace wasn't running anything. I think Greenpeace is being targeted because, while they've, you know, they've been all over the world to, to stop actions from climate change to save the whales to, you know, save the dolphins.

They were, they were merely an organization that was there as allies.

Alleen: Again, Cody waited for the knock at his door.

But again, it didn't come. In legal filings, Energy Transfer said they'd attempted to serve Cody at a home in South Dakota, where his parents had lived briefly, a decade ago.

Cody: I called up and I said, ‘Hey,’ I said, ‘You guys say you can't serve me.’ I said, um, ‘I'm sitting here at home, serve my ass. So what the hell is this bullshit?’

Alleen: A receptionist for Energy Transfer took his number, but he never heard back. For Cody, this lawsuit and not being served meant that that creeping feeling of being targeted never really subsided.

Cody: It's always a dark cloud that hangs over you, you know.

Alleen: I had been following all of this as a reporter from afar. But I was off getting twisted up in a different set of Standing Rock conspiracy theories. In 2017, months after my visit to Standing Rock, someone intriguing leaked a bunch of internal records to us at The Intercept. This person had been a contractor for a mercenary private security firm: TigerSwan. Energy Transfer had hired them to lead their security operation. TigerSwan was started in the middle of the Global War on Terror. The people working there were mostly military veterans – a lot of special ops guys.

The leaked TigerSwan records I got included daily situation reports that they wrote for the pipeline company. They described the security contractor's efforts to spy on and disrupt the Standing Rock movement. Here’s an example of the kind of analysis TigerSwan was providing:

Voice actor, our producer Ray Pang, as a TigerSwan analyst: What the anti-Dakota Access Pipeline protesters have called an “Indigenous decolonization movement” was, essentially, an externally supported, ideologically driven insurgency with a strong religious component.

Alleen: TigerSwan compared the pipeline opponents to jihadists.

Over the years, I kept tugging at threads, uncovering, bit by bit, just what it was TigerSwan was doing at Standing Rock. And what I saw was that Tigerswan wasn’t just providing physical security like armed guards, but they were conducting intelligence operations. Storytelling and deception had become a key part of Energy Transfer’s Dakota Access pipeline strategy. I had talked to so many activists and water protectors who suspected the pipeline company was infiltrating their movement. And it turns out, they were.

In 2024 it became clear that the conspiracy lawsuit against Cody Hall, the other pipeline opponents and Greenpeace might actually go to trial. I knew that a court battle would inevitably uncover even more facets of Energy Transfer's real conspiracy to crush the anti-pipeline movement. I had to keep following the paper trail. This is when I tracked down Cody's number and gave him a call.

I was surprised when I found out Cody had never been served. And to be honest, I wasn’t quite sure what to do with his story about the guy with the envelope. I couldn’t verify it. What if he was misremembering some of the details? I wasn’t even sure how $200,000 would fit in an envelope. But I couldn’t ignore the story either.

I looked up Cody's name in my cache of internal TigerSwan records. Something surprising caught my eye. It was one of the daily situation reports, and the date matched the protest where Cody met the envelope man.

I called Cody and read it to him.

Alleen: It says, ‘We did have embeds at the protest, one of which was invited to the camp by an associate of Cody Hall, one of the primary antagonists.’

Alleen: This document seemed to be saying that there were infiltrators embedded in the crowd at the courthouse protest that Cody attended in September.

Alleen: It says, At the conclusion of the protest, Cody Hall, an affiliate of the Red Warriors, invited several individuals, including a member of the security team, to return to the spirit camp with him, where the Red Warriors have their own separate camp.’

Alleen: Again: This was saying that Cody invited an undercover member of the pipeline security team to go back to the pipeline resistance camps from this courthouse protest.

Alleen: And then it says, ‘Next 24 hours, conducting atmospherics inside the camp. Continue social media and atmospheric gathering. Continue to gather information regarding potential militants in the area of protest camps. I guess what I'm wondering, is if it's possible that this protest that this is describing is the same one that you were describing where the Greenpeace guy offered you money.

Cody: Has to be.

Alleen: This private security infiltrator was with Cody on the same day that Cody met the envelope man who claimed to be with Greenpeace.

Alleen: I mean, do you think it's possible that the guy that offered this money was actually working for TigerSpawn?

Cody: Um, I mean, quite possibly,

Alleen: Both Energy Transfer and TigerSwan declined to comment on this.

So I messaged a source who had worked for TigerSwan on their intelligence operation. The source said they didn't know about anyone at TigerSwan offering up an envelope of money. But they also found it hard to imagine that a giant nonprofit like Greenpeace would operate that way.

They wrote over text, ‘Tired ass legend like Greenpeace handing out cash. It might have been when one of the feds or narcs who tried to infiltrate and failed.’

By narc, the source means someone working on drug enforcement for police or a federal agency. They figured envelope man was someone operating undercover for law enforcement.

Alleen: Meaning the feds could have been trying to frame Cody by getting him to take money.

It wasn't totally out of the question. I’d learned in my years of reporting that it wasn’t just TigerSwan that was using infiltrators. The FBI had its own network of up to 10 informants. FBI agents were entering the camp daily in plainclothes.

But when I asked Jacob O’Connell, the FBI supervisor, about this, he told me that it didn’t sound like a plausible FBI activity. He said it would have been a big deal for the agency to empower someone to walk around with $200,000, and he didn’t remember that happening.

I wasn't sure what to think.

I imagined that the trial might provide some answers to my questions. But as time went on it started to become clear that Cody had been disappeared from this lawsuit. Energy Transfer only wanted Greenpeace on trial.

The court date crept closer, and Cody still wasn't served. The other Indigenous pipeline opponent, Krystal Two Bulls, hadn’t been either. Cody had lived for nearly seven years with this multi-million dollar lawsuit hanging over his head. But somewhere along the line, he had fallen out of Energy Transfer's legal theory. They'd just never bothered to tell anybody.

Envelope man seemed destined to remain a ghost. In fact, I’ll jump out of order here and tell you that Energy Transfer never brought up him or his mysterious $200,000 during trial.

He’s important mostly just because he represents Cody’s only big memory of interacting with Greenpeace, and even then he might have been an imposter. And I think envelope man also reveals something about what Energy Transfer was working with as they crafted their lawsuit.

Every conspiracy theory contains a grain of truth. In this case, a lot of money was pouring into Standing Rock, and it wasn’t always clear from where. At the same time, the chaos and intensity of Standing Rock provided fertile ground for twisting and manipulating information.

There was one thing I knew for sure. If Energy Transfer’s conspiracy lawsuit is a bold attempt to rewrite the story of Standing Rock, then private security infiltrators creeping around on its behalf wasn’t a part of the story they meant to tell. But there they were, present during the one instance when Cody says he actually might have had contact with his supposed co-conspirator, Greenpeace.

Alleen: As I prepared to fly to North Dakota for the trial in the depths of February, I wondered what I was walking into. I knew that Energy Transfer's contractors had used deception in the past, but I also knew that the real story of Standing Rock is complicated.

Had Energy Transfer’s law firm discovered something I didn't already know about Greenpeace?

Or was this lawsuit just another deceptive trick from the pipeline company?

That’s next time on Drilled.