Drilled • Season 7 Episode 1

S7, Ep1 | The First Day of School

About This Episode

Transcript

Frontline: The Last Generation [00:00:02] I was sitting on the sea. I didn't see the wave coming. It just pushed me off and I thought it was something else and I thought it was like a monster. My grandmother told me to come to change. So I wait here and sit. Watching everybody yelling, watching the babies crying. It was not good. What can you do to cope with the impact of climate change? I think the best thing I learned is to do an action plan. I'm dedicated to this place.

Frontline: The Last Generation [00:00:44] Like, I was destined to be in this place. That's why I'm going to stay. I'm not going to leave. I'm going to stay, watch, even if it means I'm trapped.

Katie Worth [00:01:02] There the effects were already very visible and because we were doing a film, we wanted to capture it. So while we were there, we talked to all these kids and we were really struck by how much they knew about climate change, like they were more conversant in the causes and effects of climate change than most adults that I know.

Amy Westervelt [00:01:26] This is Katie Wirth. She's a reporter for Frontline, and this project she did on the Marshall Islands is really incredible. It's a super interactive, very immersive, super interesting project, I'll link to it in the show notes. But for our purposes today, this thing she said about how even really little kids in the Marshall Islands were pretty knowledgeable and conversant about climate change. It really struck me.

Dharna Noor [00:01:52] I'm pretty sure that I didn't even learn half of what those kids said until I was like well into my career as a climate reporter.

Amy Westervelt [00:01:59] Dharna Noor, Welcome to Drilled!

Dharna Noor [00:02:01] Thank you. I'm excited to be here.

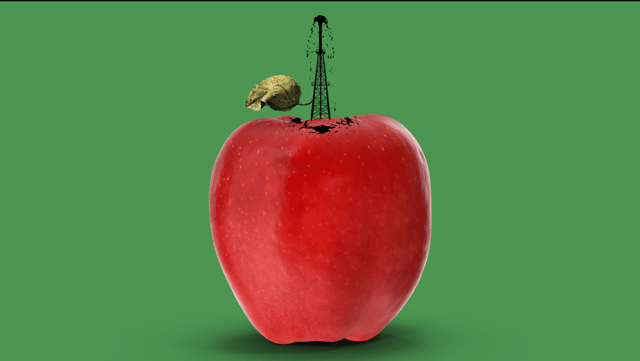

Amy Westervelt [00:02:02] If you don't already know, Darna is a climate reporter for Earther. That's Gizmodo's climate and justice site. She and I have been working together the past few months to pull together this series about the fossil fuel industry's influence on education in America, particularly when it comes to how we think about solutions to climate change. We're calling it The ABCs of Big Oil. So back to the Marshall Islands, that trip a few years ago prompted Frontline reporter Katie Worth to want to look into what American kids know about climate change.

Dharna Noor [00:02:41] Oh man! And aren't there like a ton of Marshall Islands refugees here in the US, too in Arkansas and Oklahoma?

Amy Westervelt [00:02:49] Yeah, yeah, both. So Katie went to some schools in Arkansas where there's a large Marshallese population to see what American kids are learning there about climate change and also to kind of get a sense of OK, if these kids on the Marshall Islands were to leave there and go to one of these communities in the U.S., what would those same kids be learning here? She was expecting them to know less, but she was not prepared for them to be steeped in climate denial.

Katie Worth [00:03:23] We went to Springdale, Arkansas to visit some schools there because of this connection to the Marshall Islands, because it's such a large Marshallese community in Springdale. And so I went and visited a few different schools, and one of them was a middle school, and I started talking to the science teachers and in walks this lobbyist for the oil and gas industry.

Amy Westervelt [00:03:56] Katie actually shared some of the audio she recorded during that visit.

Arkansas fossil fuel lobbyist [00:04:01] And part of the way we are meeting the demand for more energy here in the U.S. is we had some transformative technological advances. It used to be that in a section, we would drill thirty six hours straight down the track thousands of feet. Then in the early 2000s, an engineer from Texas, George Mitchell, invented a drilling motor that would go down thousands of feet and turn out horizontally or laterally. They call it kickin' out. Today we have wells that kick out up to two miles. So when he did that, that changed everything. They combined horizontal drilling with something we've been doing for a long time, hydraulic fracturing...

Dharna Noor [00:04:42] Oh my god, that's unbelievable. But we've been hearing about this sort of thing, right? Natural gas companies handing out pamphlets in schools, sending people out to talk to the youth.

Amy Westervelt [00:04:53] Yeah, yeah, totally. But usually they focus on either how great it is to work in the oil and gas industry or on skewing the science in some way. Katie ended up writing about how American schools teach climate change in her new book, Miseducation, and she included something from this woman's presentation that really just floored me, especially when you keep in mind that this was a seventh grade class.

Katie Worth [00:05:22] A lot of what she was talking about was kind of legitimate information like, you know, how oil is taken from the ground and the machinery that does that and kind of the geology of it all. But then she got into talking about carbon emissions, and she didn't really explain what carbon emissions were. She didn't explain why they might be a problem. They said She said that it would be a problem, but she didn't explain anything about global warming or climate change, but instead immediately immediately launched into this kind of list of all the problems that exist with all of the different fuels. So like solar, if it's cloudy, you don't get energy and wind mills kill birds and so on.

Amy Westervelt [00:06:09] Here's that part of the lobbyist's presentation

Arkansas fossil fuel lobbyist [00:06:13] But with any energy source. I mean, this problem with fossil fuels in terms of carbon emissions, there's problems in all these energy sources. Somebody's going to have a problem with it. Geothermal power's great. Super expensive. The parts, the labor, that works really well, but it's expensive. Solar. That's what that the materials used to make solar panels? Some time when you have a chance look up rare earth minerals. Some of those things that they make them with are not things that you would want laying around in your yard. Another thing with solar? If there's a tornado, what happens to the solar field? In Arkansas, we have tornadoes. Wind power, a lotta people don't like because they saiy it kills the birds. There are a lot of people don't like hydro power because they say that we shouldn't be damning up bodies of water. Lotta people don't like biomass because they said we shouldn't be growing food for fuel when people there are people starving, and there are. So you're going to find a problem and any one of these sources.

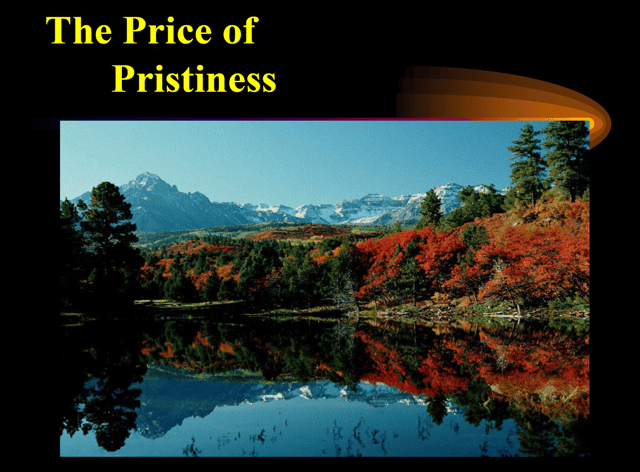

Katie Worth [00:07:23] And then she talks about how important fossil fuels are to the world and how how they've lifted people out of poverty. And if we stop using fossil fuels, we'll leave a whole bunch of people in poverty, according to her, which is not supported by evidence. But you know, that was the narrative that she was telling. So she was talking about how when you're considering energy, you have to do some thinking about your values, she says. First of all, you need to decide your standard of value. You need to decide is human life, the most important? Humans getting healthier, wealthier, happier, living longer? Or is pristine nature more important? Do you want to quit building new houses? Stop getting stuff out of the ground? Do you want to leave it exactly as it is? Because that would be difficult. Thankfully, we don't have to choose in this country. We are working on a happy medium at this point,

Dharna Noor [00:08:16] A happy medium. Tell that to all the people evacuating hurricanes and fires and floods this year. And this really gets to the heart of what we wanted to focus on in this series. Because you're right, we know a little bit about how oil companies try to shape the way kids understand the problem and the science, and that's really bad. But then there's this other thing that seems so much more insidious and potentially like an even bigger problem.

Amy Westervelt [00:08:40] Yeah, exactly. This way, the industry positions itself in the world and in people's lives and in the economy, and the way it tries to frame what is or isn't possible. It's like all of the solutions to climate change have been narrowed before we even start.

Dharna Noor [00:08:59] So that's what we're going to look at in this series. Why and how the fossil fuel industry invaded social science curricula and what impact that's had on how Americans approach these big problems like climate change and how to stop climate change

Amy Westervelt [00:09:14] Over the next four episodes will trace the industry's influence from elementary schools through to universities. But first, how did the fossil fuel industry get into schools in the first place? That's today's story coming up after this quick break.

Ad [00:09:46] I mean, good scientists, they have the minds of children. One man's pursuit, he set up a chemistry lab when he was 12 changed the very air we breathe. Holy smokes this hideous crime. We were committed. We mean rock.

[00:09:59] It's everywhere, turns into like thorium,

[00:10:02] then turns into radon and turns into bismuth. It's accidental.

[00:10:06] I see it as the majesty of gods hanging from Radiolab heavy metal. Listen wherever you get your podcasts.

Destination Earth (API) [00:10:21] And using the magic of research, oil companies compete with each other in taking the petroleum molecule apart and rearranging it into, well, you name it, every toothbrush, tires insecticide. Cosmetic weed killers, home galaxy of things will make a better life on Earth, and, you know, it isn't just oil companies that try to outdo each other competing for the customers dollar. The same story is true of almost every successful business enterprise in America.

Standard Oil, Oil for Aladdin’s Lamp [00:11:01] Some of the miracles of petroleum are familiar to us all we know, for instance, that oil made possible one of the greatest inventions of history. The internal combustion engine, which gave us mastery over the air, meant mass transportation. While the world changed, the face of continents quickened the very pulse of civilization provided man with an ease of living.

Dupont Magic Barrel [00:11:29] This is the Magic Barrel of your life. And we've opened it so we can show you some of the modern day miracles that it contains that were made with the help of Petro Chemical. Which means chemicals from petroleum.

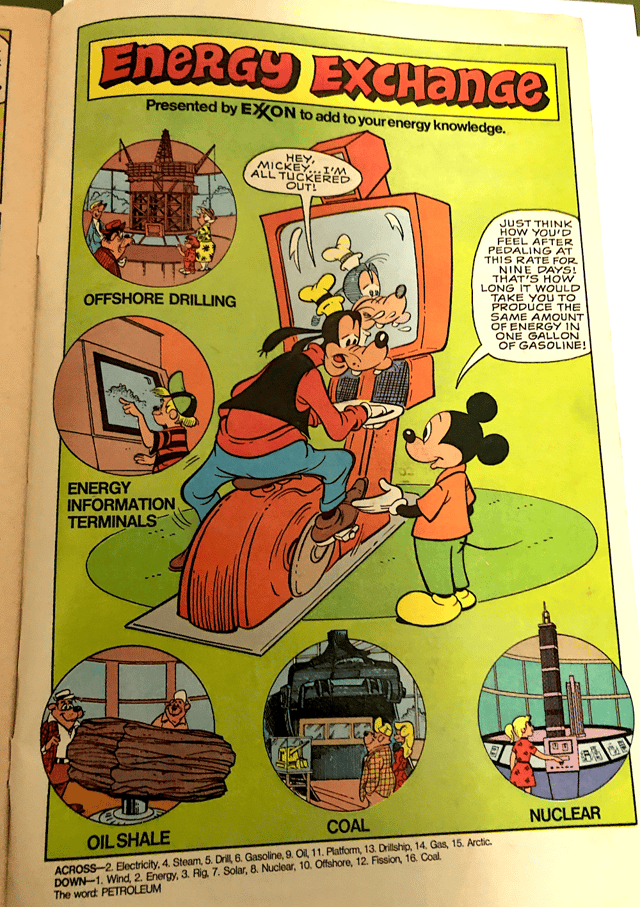

Amy Westervelt [00:11:56] The 1950s were a real heyday for corporate sponsored pro-capitalist infotainment. That last one there was called the Magic Barrel. It's an early example of an industry funded curriculum used in schools. It was actually a partnership between DuPont and the American Petroleum Institute to promote petrochemicals. The barrel in question is actually an oil barrel. Magic! But you can hear a common thread through all of these that links oil to capitalism and American identity and reminds you that your entire life revolves around this stuff.

Kert Davies [00:12:34] There are very interesting common themes. Energy is vital to your life. Your whole existence is dependent on energy. You better love us. We make energy for you. It's super effective to show somebody whether they are conscious of it or not, how much they're dependent on fossil fuels.

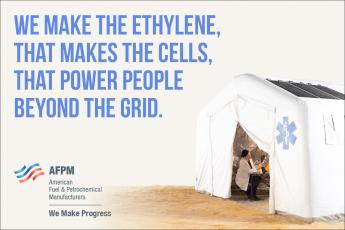

Dharna Noor [00:12:56] That's Kert Davies, and he's the founder and director of the Climate Investigations Center. He spent the last 20 years or so researching fossil fuel propaganda, and he's found a lot of it in schools. One thing he said he's noticed is that oil companies and industry groups like the American Petroleum Institute will often combine a curriculum package that's targeted at kids with these ad campaigns that are meant for their parents,

Kert Davies [00:13:21] so that the ad campaigns that are aimed at the parents through whether it's American Petroleum Institute or Exxon broadcasting during sporting events, mimic or mirror what we see in these curriculum packages of showing how you know how cool energy is, how it creates jobs, how it's the lifeblood of our economy, how we can't live without it, and how changing that would hurt you.

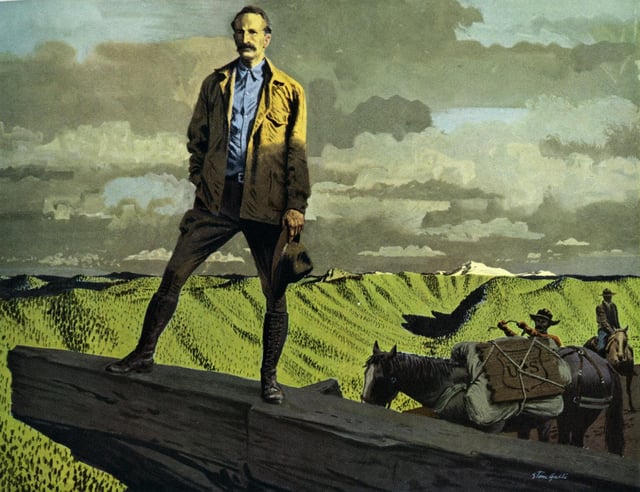

Amy Westervelt [00:13:50] There are some early examples in the 1940s of Standard Oil and the American Petroleum Institute sending materials to schools that are very pro oil and pro-industry. But the practice seems to have really ramped up during the Cold War in the 1950s, when the industry felt the need to remind Americans over and over again how prosperous and happy oil and capitalism had made them. Then you see the same sort of messaging explode again in the 1970s as a reaction to the social movements of the 1960s. There's this incredible series that Phillips Petroleum commissioned called American Enterprise.

American Enterprise [00:14:32] When we needed coal and iron, the raw materials of the Industrial Revolution. We had them right under our feet.

Amy Westervelt [00:14:39] It came out in the 1970s, and it's hosted by William Shatner. And it just kind of very subtly and persistently delivers this message that America is great because of extraction and capitalism

American Enterprise [00:14:53] here in our backyard. When we needed petroleum, we had it. Black gold in Pennsylvania and the southwest. When we needed uranium for nuclear power, we had it. Our hills old enough to last for centuries. The land has provided on a grand scale. This open pit copper mine in Utah you're looking at is so large you can see it from the Moon. Thanks to the Earth's bounty, we've increased and multiplied at a rate unmatched by any nation in history.

Dharna Noor [00:15:26] Yeah, that whole series is really something, and not just because you hear William Shatner's voice in it so much. And we know from marketing reports that this was sent out to more than half of American high schools in the 1970s. Obviously, that wasn't the only thing that people were learning about in terms of economics or politics or natural resources in high school, I hope. But that's still a lot of people who are getting the same narratives that you now hear really often in response to climate policy proposals. Yeah.

Amy Westervelt [00:15:55] So, OK, you see this pattern throughout history where the industry steps up certain types of curricula when they feel ideologically threatened, and there are lots of reasons they might want to have a hand in shaping the minds of future voters and politicians. But why would schools go along?

Dharna Noor [00:16:15] Well, we kind of heard the same thing from everyone.

Kert Davies [00:16:19] Education's underfunded, so that's a vulnerability.

Katie Worth [00:16:23] I remember talking to one person who is like, Look, I barely have three minutes in my day to pee. So if somebody sends me this lesson plan and it's like a really well produced and looks very professional, I might use it.

Kert Davies [00:16:39] So these people who make their own curriculum take advantage that they give away free lesson plans. That's great. If you're a teacher and you suddenly get this whole kit, it's set up for you to teach science through teaching about energy or teach, you know, teach about economics. It's like easy, easy stuff.

Katie Worth [00:17:00] And what they usually do, some of them are like outright climate denial. But then there's a lot of materials that are much subtler, and you wouldn't necessarily catch if you weren't like really looking for it.

Dharna Noor [00:17:15] OK. So teachers are overworked and underpaid, and at the same time, schools are underfunded. So if you're producing this really slick looking curriculum, it's really not that hard to get it into schools. And then we also found in our research that companies have targeted groups like the National Science Teachers of America and even the Department of Energy to get them all to push these really industry friendly curricula. And Katie talked about another type of organization, too.

Katie Worth [00:17:42] There's an organization called the National Energy Education Development Project. I think Their whole purpose is to create educational materials about energy, which seems like a good thing, you know, and they talk about energy conservation. They talk about every all kinds of energy, including some renewables, which in theory, sounds like a good thing, but they are sponsored by all of these energy companies, and some of them are, you know, wind or solar companies. But most of them are fossil fuel companies. And that's how they get the vast majority of their budget. And so they told me that they aren't influenced by their sponsors. But then if you actually look at the materials they produce, it's really industry friendly. And so like, for example, they have this whole set of these packets of things for of activities and lessons for different age groups about all the different energy sources. And there's like 14 pages of information and activities about petroleum. Nowhere in those materials is carbon dioxide mentioned. Climate change isn't mentioned, and the only environmental impacts—so they do talk about environmental impact, but what they talk about is water pollution or air pollution. And then they say, I think I'm going to quote this directly. And then there's a paragraph that reads, The petroleum industry works hard to protect the environment. Gasoline and diesel fuel have been changed to burn cleaner and oil companies work to make sure that they drill and transport oil as safely as possible.

Amy Westervelt [00:19:31] So this really gets us back to what's in it for the industry. For more on that, we had Carroll Muffett, president and CEO of the Center for International Environmental Law, walk us through a presentation he found where a well-known oil industry consultant laid out why investing in building education programs was a good idea for the industry. Carroll took us to Zoom school.

Carroll Muffett [00:19:58] This presentation is being presented against the backdrop of an industry that has been doing this aggressively and somewhat successfully for years. And I think it's really important to note that the presentation is given by a guy named John Tobin, whose expertise was not in education. His expertise was in speculating about oil and gas, but he brought something valuable to the table, and nowhere is that value clearer than in the the names of the inaugural board members that signed on to his Energy Literacy Project. Here he was with a tiny, tiny nonprofit, but you've got senior executives from Chevron and Phillips both on this board. He's got an executive, the head of a Koch funded think tank that advocated for property rights and free-market environmentalism. He had Pennsylvanian Power and Light, which was a major coal plant operator at the time and a member of the Global Climate Coalition.

Dharna Noor [00:21:08] I think it's really important for everyone listening to kind of have a picture in their minds of what this presentation looks like because it's really something there's a black background and this weird neon orb thing at the top of every page.

Amy Westervelt [00:21:20] It's truly, truly a lot. Very, very good example of like late 90s, early 2000s graphic skills.

Dharna Noor [00:21:28] And there's all these quotes and clip art and these bizarre stock photos. This one slide that I love just has an illustration of an elephant with the saying "When eating an elephant, take one bite at a time." So deep! But then there's this one thing that this guy, John Tobin, who made the presentation, seems to really want to drive home to people. And that's something that he calls the three Es: and that's energy, economy and environment, and they're in that order for a reason. OK, back to Zoom School,

Carroll Muffett [00:22:01] I want to start by both talking about the three Es and highlighting what the three Es mean for industry. And Tobin's presentation is compelling because it's so very explicit about that. The three E's that were pushed into classrooms by ExxonMobil for decades stood for energy, economy and environment. And in that order, and we'll talk about why that order is important as we go along. This presentation is making the case for why those three Es are so important to the industry in itself. What Tobin highlights is that the oil and gas industry suffers from severe image problems, and educating around the three E's is key to addressing those image problems and, with it, making the companies themselves more profitable. Next slide...

Amy Westervelt [00:22:58] There are more than 50 slides in this presentation, so we're going to skip ahead to the highlights.

Carroll Muffett [00:23:03] And again, bear in mind that he's speaking on behalf of an organization that has senior executives from many of the industry's largest companies behind it. What they're looking to instill is a belief in a "28th amendment": that the people's right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness shall be fueled by cheap and abundant energy. Yet again, equating energy not only with the economy, but with liberty and freedom itself. This presentation happened in the wake of what was, in fact, a major victory for these programs because in the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which was recognized at the time to be filled with massive giveaways to the oil and gas industry. And part of what was incorporated were provisions for millions of dollars for educational programs focused specifically on the three Es: on energy, economy and environment.

Dharna Noor [00:24:16] OK, hold up a minute. I just want to make sure that everyone caught that. The U.S. government put millions of dollars toward pro oil industry energy education in 2005. So a good like 30 40 years after several scientists had already been sounding the alarm about climate change.

Amy Westervelt [00:24:33] Yeah. And after world leaders had agreed to come together and reduce emissions because everyone understood the problem was that bad. Until the U.S. just said, just kidding, we're out.

Dharna Noor [00:24:44] You're talking about the Kyoto Protocol, of course. And yeah, this is two thousand five. So that's just a few years after the US Senate voted ninety five to zero against ratifying Kyoto, and president, George W. Bush, officially pulled out of the agreement. And now the government wasn't just not taking any action, it was actually funding an industry-friendly take on energy education in American schools.

Carroll Muffett [00:25:07] And at the moment that he's presenting to SPE [Society of Petroleum Engineers] what he's acknowledging here is that between DOE and IOGCC, which is the independent oil and gas companies, there were more than 300 active school outreach programs. And I think most fundamentally, you see the explicit equation of the economy with freedom. The economy is economic growth. The economy is freedom. And when you know that economic growth is dependent on energy, anything that you do to restrict the growth of energy is restricting the growth of the economy and is a threat to your freedom. Again, the targets for this were kids from kindergarten through college. And when you do that, when you take your message and you put it in the mouth of someone who is teaching your children who children are told to believe and trust, it is among the most insidious and among the most effective forms of propaganda. And we are still dealing with and reeling from decades of that propaganda.

Amy Westervelt [00:26:26] That last part really, really hits home for me, because when you think about especially little kids, I mean, you really trust what your teachers tell you in school, at least for a while.

Dharna Noor [00:26:38] Yeah, it's so cynical and it's honestly, really smart of them. I was really struck by how much funding was going into this and how many government programs there were at that point, and probably now too, honestly. But the fact that there were over 300 back in 2005, that's pretty incredible.

Amy Westervelt [00:26:57] Yeah. One thing that really struck me in looking not just at this presentation that Carroll Muffett was talking about, but also at various materials that we found is that they're just filled with what sociologists have started to call discourses of delay. That term comes from this paper that came out last year. It was written by an economist named Will Lamb, and several other economics and social science researchers who just started to pull together examples of messages like these that the industry uses and that we see over and over and start to catalog them and categorize them into groups.

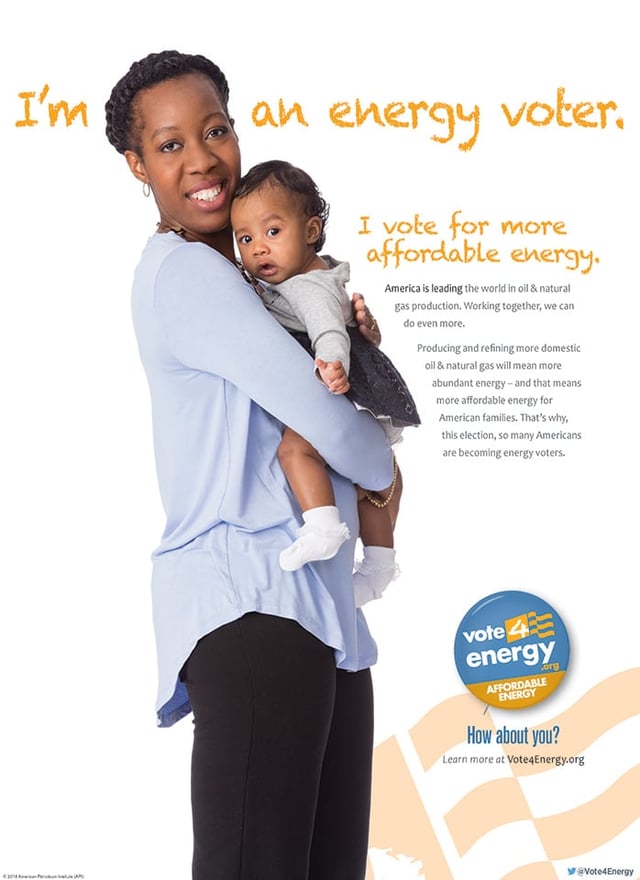

Dharna Noor [00:27:36] Yeah. So these are these messages that have sort of taken the place of straight up climate denial. Amy's done some great writing on that, and a lot of them have been around for like a century or more. They're things like the importance of fossil fuels in America or how on top of problems the fossil fuel industry is or how so-called cheap energy keeps everyone out of poverty. Here's Carol Moffett again.

Carroll Muffett [00:28:01] We we see Exxon Mobil having pushed its Energy Cube training materials in schools across the country for decades, making Exxon Energy Cube one of the most widely used educational resources in the entire United States for literally tens of years. And so the question becomes What is that Energy Cube? The Energy Cube stood for energy economy and the environment and the entire strategy behind it. And we see the oil industry push this over and over again into the mainstream with kids. The idea that the that energy is absolutely essential to not only the economy, but ultimately to freedom, that you can't have a functioning economy without energy, that anything that accordingly anything that restricts or regulates energy has an immediate effect on the economy. And therefore, whenever you talk about the environmental impacts of energy production in any form, you immediately have to weight those environmental impacts against their presumed economic impact.

Dharna Noor [00:29:17] Does that all sound familiar?

Amy Westervelt [00:29:19] I mean, it's really striking to me just how often you hear these exact talking points even from, you know, moderate Democrats who think we do need to do something on climate, but it's like they just have this framework in their heads. It's been a super effective strategy. And one of the reasons that's been effective is exactly this thing that Katie Wirth was talking about. It's not denial. So it kind of has this veneer of credibility.

Will Lamb [00:29:48] You're allowed to legitimately discuss delay in mainstream context. So it's more difficult to promote climate denial these days, I think, because, for example, the BBC has now quite strict guidance on the kind of balance that it's going to offer in its interviews around climate change, so they don't invite on a dissenting view on climate science anymore.

Amy Westervelt [00:30:13] This is Will Lamb, the lead author of that discourses of delay paper,

Will Lamb [00:30:17] and I think that's happened more and more, and it's more difficult to discuss through denial in the public arena. But delay is tricky. Delays tricky? Because often there are grains of truth in delay arguments and often, you can posit, is really a legitimate discussion on what the shape of climate policy should look like.

Dharna Noor [00:30:39] Right. So then the issue becomes like if we want to separate the credible stuff from the industry talking points, do we need all teachers to be these experts in climate disinformation? That's just completely unrealistic

Amy Westervelt [00:30:52] Totally. If one of the reasons that this has worked so well is that teachers are stretched really thin and schools are underfunded, the solution can't be that they need to take on more work and become experts in this field. So, you know, you can see how being bombarded with all of this reasonable sounding stuff about trade offs and the need to keep energy affordable and how on top of environmental issues the industry is might lead to a whole lot of inaction on climate. But that's not the only reason fossil fuel companies do this stuff. Is it Dharna?

Dharna Noor [00:31:27] That's right. There's more. Here's Kert Davies again.

Kert Davies [00:31:30] Why do they need this? Because they want to be more popular than they are. You know, most people in the oil industry is not very popular. The coal industry is not very popular or may bemoan the fact that nobody knows where they where you get your electricity and they want people to understand that. So I mean, you see you have these fossil fuel interests or electric utilities, coal oil interests who have been craving, craving attention and craving acceptance and social license for a good long time. And they have tried to do that with a variety of things and often in in conjunction they'll do curriculum. But they also are doing an ad campaign on television or in in local newspapers.

Dharna Noor [00:32:20] And then Carroll Muffett, again from the Center for International Environmental Law pointed out that schools are also really big recruitment targets for the oil industry, especially now when fewer and fewer younger people are interested in working for them for obvious reasons. In 2014, former Exxon CEO and later Trump administration appointee Rex Tillerson actually talked pretty openly about the role that education can play in this really, really gross way. He said that schools are, quote, producing a product, and that product is the students going into the workforce.

Carroll Muffett [00:32:54] To summarize Rex Tillerson, the oil industry got involved in education because for the oil industry, the students are the product. And I think when Tillerson said that he was obviously talking in the context of workers and future workers and prospects. But what you see when you look at the history of the oil industry's engagement in education is that for the whole industry, the students are the product in a much more profound and extensive and pervasive way.

Amy Westervelt [00:33:29] Oh, that yeah, that really is really is gross. OK, so I don't want to end this episode without talking about a side of the school curriculum game that people might not necessarily think of. And that's universities, right?

Dharna Noor [00:33:45] So oil companies actually fund research centers at all the top schools even the mighty Harvard and Stanford. But that's not the only way that they get involved on on university campuses, either.

Amy Westervelt [00:33:57] Yeah, that's right. They also fund chairs and economic departments or law schools or programs at public policy schools. Oil companies were actually among the first to see universities as a huge opportunity. So there was this kind of small, seemingly obscure tax law change in the 50s that made corporate donations to universities a write off. And that prompted a little bit of an increase in industry funding at the university level, but a lot of corporations just kind of saw it as the tax break. And there was this VP at Standard Oil of New Jersey, which is now ExxonMobil. His name was Frank Abrams, and he started to really see this as a golden opportunity for way more than just, you know, some nice tax breaks. He started talking to everyone in the oil industry and beyond about, you know, really what they could do here. I found this speech of his from 1953, where he's like, Yeah, yeah, the tax break is great, but don't forget all this other stuff. So he says "the important thing is that corporate gifts should be made when the direct or indirect benefits—and I want to underscore indirect benefits—are worth more to the company than the costs after tax adjustments." And then he goes on to give an example of one of these great indirect benefits. He says, "there is a tendency on the part of some people to call on the government to take over more and more functions and responsibilities borne previously by citizens. My observation of political history, both here and abroad during 40 years with Standard Oil Company, provides evidence of how this thinking can develop even in a soil like ours, where the tradition of democracy and free enterprise is well-developed. Each time government takes over a new function, the free society shrinks by that much. A step has been taken toward statism, a system holding great dangers for the general well-being of the country. And incidentally for stockholders' investments in corporations. This is a problem with great dimension, in my view, but I think finally, we can rely on a prudent and mature people—that is and educated people—to deal properly with it."

Dharna Noor [00:36:28] So, yeah, it seems seems like oil executives and oil companies have really been worried about creeping socialism for a long time.

Kert Davies [00:36:36] They really, really have been. And they really spent decades looking to use education as a tool to solidify their position in society. That's it for this time. We're taking you to school in this collaboration between Drilled and Earther. Dharna and I have found a lot of really interesting and shocking things. So stay with us.

[00:37:10] Drilled is an original production of the Critical Frequency podcast network. This series is a collaboration with Earther, Gizmodo's climate and justice site. My co-host and co reporter for the series is Dharna Noor. Our producer is Juliana Bradley. Our fact checker is Trevor Gowan. Music is by Martin Weissenberg, and our artwork was created by Matthew Flemming. Our First Amendment attorney is James Wheaton, founder and director of the First Amendment Project. You can find corresponding stories, videos and documents for this series on earther dot com.

Dharna Noor [00:37:47] Thanks for listening, and we'll see you next time.